On the late afternoon of Jan. 10, 1871, Juan Soto and two other bandidos rode north out of San Jose on the old Stockton road, which led up into the Livermore Valley. Two hours later they dismounted at Scott’s Corners in the Sunol Valley (near the present-day intersection of I-680 and Vallecitos Road) and hitched their horses outside Thomas Scott’s store and trading post. Scott, his wife and two young sons lived in rooms behind the store. At that hour they were warming themselves by the fire in the company of store clerk Otto Ludovisi and two visitors.

Hearing a knock at the door, Ludovisi rose to answer. It was a bearded Californio, booted and spurred, wearing a wide-brimmed dark hat. The man purchased a bottle of whiskey and left. Ten minutes later there was another knock, and Ludovisi again opened the door. This time in stepped Juan Soto and his two compadres, six-guns in hand, bandannas concealing their faces.

“Get out of here!” a terrified Ludovisi shouted. “Get out of here!”

“Say nothing! Say nothing!” one of the bandidos ordered. Then, without provocation, he raised his pistol and fired. That gunshot signaled the beginning of the end for one of California’s most notorious outlaws, who soon met his own fate during a shootout with a fearless lawman.

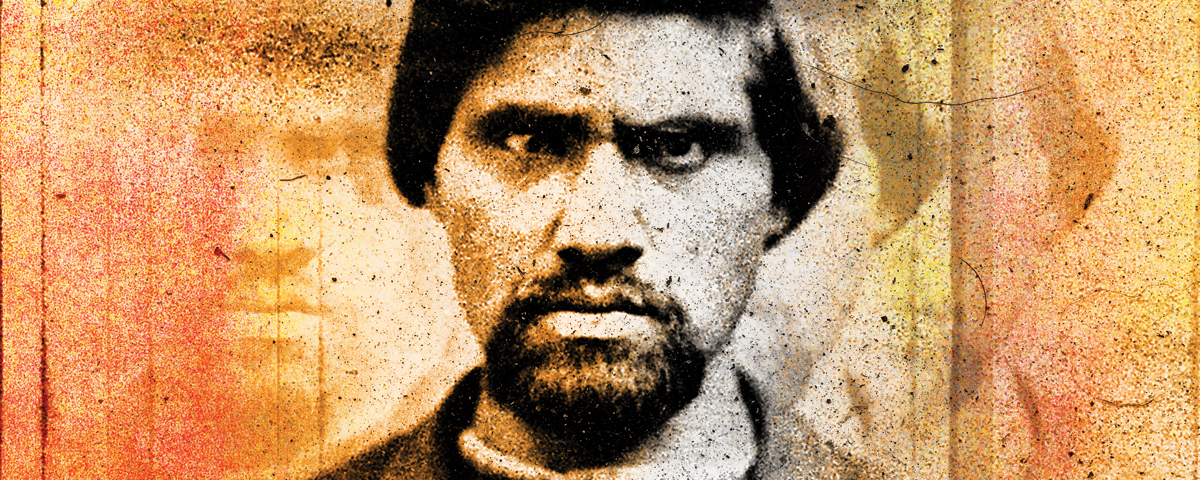

Soto presented a terrifying figure, with wildly crossed eyes and a heavily bearded, badly pockmarked face. He reportedly had a temperament to match

Juan Bautista Soto was born on Feb. 2, 1846, to José Francisco Soto and Maria Carmen Flores in what four years later became Santa Clara County. He came from pioneer stock: His grandfather Ignacio Soto had journeyed to California with the 1776 Juan Bautista de Anza expedition. He also came from bandit stock—his maternal uncle Sebastian Flores was a notorious California brigand and a member of the Francisco Garcia gang of robbers in the 1850s.

By 1860 14-year-old Juan was working as a vaquero on Daniel Murphy’s cattle ranch some 30 miles south of San Jose. At 19 Soto weighed 200 pounds and presented a terrifying figure, with wildly crossed eyes and a heavily bearded, badly pockmarked face. Nick Harris, later sheriff of Santa Clara County, described Soto as “a perfect type of desperado, over 6 feet high, well proportioned and quick as a cat, with a countenance the worst I ever saw in a human face.” He reportedly had a temperament to match—easily angered and driven by hatred for the Anglos who had taken over the land of his birth. His ferocity earned him the nickname the “Human Wildcat.” A superb horseman and dead shot, he knew every inch of the Santa Clara Valley and flanking Coast Range.

By age 19 he’d graduated to highway robbery. On the night of May 4, 1865, Soto, with compadres Francisco Salazar and Jesús Sanchez, held up hotelkeeper Julius Weitzel on the road between San Jose and the New Almaden Mine, taking his purse and his horse. Then they stopped another traveler, relieving him of a blanket and 50 cents. Finally, they tried to lasso passing rider John Winters, who ducked the rope, put spurs to his horse and escaped.

Alerted by Winters, Santa Clara Undersheriff Richard B. Hall investigated and fixed his suspicions on Soto, who was still working the Murphy ranch. Hall drove his buggy to the ranch and hid it in the chaparral overlooking a pasture where Soto and fellow vaqueros were tending cattle. Waiting until Soto’s companions trotted off, the undersheriff strode from cover. “He was humming a gay little Spanish ballad,” Hall recalled, “and did not notice me until I had him covered with my pistol.”

“Get off that horse,” Hall called out in Spanish, “and lie down upon your face quickly!” Soto complied. “I made him put his hands behind him,” the undersheriff recalled, “and then, putting my pistol in my pocket, I handcuffed him.” Hall marched Soto to his buggy, bundled him aboard and whipped up his horse. By then several of Soto’s compadres had spotted his riderless mount. “A moment later,” Hall said, “swift hoofs echoed behind us, and loud voices called to us to stop. I only drove more rapidly, for I feared they would attempt to release him. On they came, and I grasped my pistol, determined to sell my life, if necessary, as dearly as possible. My chief fear was that they would use the lasso. They stopped when they reached me, however, and asked angrily what I meant by taking Juan away. I told them of his offense, and that I was the sheriff.”

Soto’s friends did not interfere, and Hall lodged his prisoner in the San Jose jail. A grand jury indicted Soto for robbery, but the case never came to trial, presumably for lack of evidence. That fall Soto, with Alfonso Burnham, Manuel Rojas and another bandit, raided the Charles Garthwaite ranch and trading post near Pleasanton in Alameda County. The owner’s wife, Mary Garthwaite, was alone, but she grabbed a pistol and shot and wounded Burnham. The outlaws overpowered the plucky woman and tied her hand and foot before fleeing with money, Mary’s jewelry and her pistol. Lawmen captured the wounded Burnham, but Soto and the rest escaped.

By 1867 Soto was riding with several notorious desperadoes, among them Francisco “Pancho” Galindo. In late March the pair stole a valuable saddle horse from Milpitas rancher Gordon Chase and fled to the Guadalupe Mine, 10 miles south of San Jose, which supported a bustling Hispanic mining camp—a favorite hangout of bandidos and fugitives. A few days later Santa Clara County Deputy Sheriff Robert H. McIlroy spotted Soto at the camp, still in possession of the stolen horse. When the suspect refused McIlroy’s order to surrender, the deputy drew his six-gun and threatened to open fire.

“Shoot and be damned!” Soto yelled in English as he darted into a saloon. McIlroy charged his horse to the rear of the building, arriving just as his quarry burst out the back door. The deputy ordered Soto to halt, but the fugitive jerked his pistol and fired. McIlroy then leaped from his horse, and the two engaged in a running gunfight, trading shots at close range. One of McIlroy’s pistol balls penetrated the skin at Soto’s temple, creased his skull and exited behind an ear. At that moment several Hispanic women rushed from the mining shacks to screen the fleeing desperado. A disciplined McIlroy held his fire and enlisted help from one Bill Williams, the only Anglo present. Williams quickly mounted the deputy’s horse and rode to head off Soto, while McIlroy pursued him on foot.

Williams managed to catch up with the wounded fugitive on the road leading from the mine. But by then Galindo had joined Soto, and the pair opened fire on their pursuer. The shots spooked Williams’ horse, which bucked and threw its rider to the ground. As Williams fumbled for his revolver, McIlroy crested a nearby hill. Choosing not to push their luck, Soto and Galindo fled into the scrub and disappeared.

San Jose lawmen later picked up Soto. Tried and convicted for stealing the horse, he served a year in prison at San Quentin. On his release in October 1868 authorities returned him to San Jose to stand trial with Galindo for shooting at Deputy Sheriff McIlroy. A jury found both men guilty, and Soto returned to San Quentin to serve a two-year term. In prison he associated with notorious bandidos Tiburcio Vásquez and Procopio Bustamante. On Aug. 27, 1870, Soto left San Quentin for the last time.

Soon after his release Soto married Galindo’s sister Nicolasa. But domestic life held little appeal, and he spent much of his free time playing billiards with friend Bartolo Sepulveda at the Auzerais House, a popular San Jose hotel. “[Soto] would stand for hours with his back against the wall close to the saloon entrance, gazing steadily into space,” recalled one San Jose pioneer. “At the time he was suspected of complicity in many highway robberies and cattle-stealing raids, but as the officers had no evidence to warrant arrest, he was not molested.”

In late November 1870 Soto’s saddle partner Sepulveda faced trial in San Jose for cattle theft, but a jury acquitted him. Two weeks later the pair rode out of town and crossed the Coast Range to the San Joaquin Valley, where they found honest work on a hog ranch near Modesto. On Jan. 8, 1871, they rode back across the mountains, passing through the Livermore and Sunol valleys. The next afternoon they rode through Scott’s Corners and on to the settlement of Mission San José (present-day Fremont). After a stop at a local saloon, they continued south to Warm Springs, where they stopped for a drink with one of Sepulveda’s cousins.

A few miles more took them to Milpitas. Sepulveda’s estranged wife, Maria, was the daughter of prominent ranchero José María Alviso, owner of the sprawling Rancho Milpitas, where she lived with the couple’s five children. Fed up with Bartolo’s drinking, gambling and stealing, Maria had returned home with her family’s blessing. Soto and Sepulveda stopped by a local saloon, where Bartolo’s acquaintance Alexander Anderson bought a round of drinks and tried to convince his friend to return to his wife. Sepulveda demurred, insisting she was better off without him. He and Soto then mounted up and rode into San Jose, arriving late that afternoon.

Late the next day, January 10, Soto and two compadres rode up to Thomas Scott’s store. It was just after 7 p.m. when they confronted clerk Otto Ludovisi at the front door with drawn pistols and put a bullet in his chest. Ludovisi managed to stagger into the back room before dropping to the floor. A horrified Scott, his family and friends fled in terror out the back door. The outlaws threw several shots at them before Mrs. Scott clutched her sons close and cried, “For God’s sake, don’t shoot!” The bandidos held fire and let them go.

Soto and his men then looted the store and rode off with their paltry spoils—$65 and a bundle of clothes. Alameda County Sheriff Harry Morse and deputies were soon on the scene. Identifying the outlaws’ tracks, the intrepid lawman and posse trailed them south. But after an intensive four-day hunt that took in all known outlaw haunts in the Santa Clara Valley, they came up dry. Morse then led his men back to Scott’s store to retrace the killers’ path. The trail led them through Milpitas past José María Alviso’s rancho. There Morse interviewed Bartolo Sepulveda’s brother-in-law, who showed the sheriff a bundle of old clothes he claimed to have found by a creek behind the house. The clothes were those stolen during the robbery.

Morse and his deputies interviewed several people who had seen Soto and Sepulveda ride through the Sunol Valley, hitting the saloons the day before the murder-robbery. Their testimony and the discovery of the stolen bundle convinced the sheriff that Soto and Sepulveda were his prime suspects, and that they had cased the store while riding through Scott’s Corners. An Alameda County grand jury promptly indicted Soto, Sepulveda and the latter’s brother, Miguel, in absentia for the murder of Otto Ludovisi. Authorities later determined the Sepulveda brothers were innocent, because at the time of the murder-robbery a heavily intoxicated Bartolo had been visiting Miguel behind bars in the San Jose jail. Soto remained on the loose.

Juan Soto fled into the remote wilderness of the Coast Range. One of his uncles had a small ranch near the Saucelito Valley (not to be confused with the town of Sausalito), 12 miles south of Pacheco Pass. Among the most isolated spots in California, the area was home to just five adobes. Joining Soto in the valley that spring were Tiburcio Vásquez and Procopio Bustamante, by then the most notorious living bandidos on the Pacific Coast. Procopio boasted prime outlaw lineage, as one of his uncles was the late Joaquín Murrieta, foremost bandido of them all. Vásquez and Procopio had recently been released from San Quentin, and with Soto they made their headquarters at the Alvarado adobe, 2 miles south of the valley proper.

From time to time they slipped into San Juan Bautista, at the western foot of the Coast Range, to drink, gamble and carouse. On May 5, 1871, Vásquez and two other outlaws, probably Soto and Procopio, stopped the Los Angeles–bound stage at Soledad, 45 miles south of San Juan Bautista. Unfortunately for them the Wells Fargo box came up empty, and they rode off in disgust without bothering to rob the passengers. The desperadoes returned to the Saucelito Valley, where four days later Soto and Procopio had a bitter quarrel. “I was there,” Vásquez recalled. “Soto made Procopio go down into his boots. If Procopio had not left like a coward, Soto would have killed him.”

Vásquez and Procopio rode down to San Juan Bautista, leaving Soto behind. It was the luckiest break of their lives. The next morning, May 10, a heavily armed, nine-man posse led by Alameda County Sheriff Harry Morse and Santa Clara County Sheriff Nick Harris crested a rocky saddle on the west side of St. Marys Peak. Morse had been hunting Soto relentlessly for weeks, making repeated treks into the Coast Range. Two days earlier he’d received a telegram from Harris in San Jose, sharing a tip Soto was hiding in the Saucelito Valley. Morse rushed to San Jose, where the two officers quickly raised a posse and started into the mountains.

On the morning of May 10 Soto and friends butchered a beef for a fiesta later that day. With them were Bartolo Sepulveda and several other hard cases. Soto and Sepulveda rode to the adobe of Juan López, at the northwest end of the valley, to get onions and salt for the barbecue. Soto was socializing with, as one early chronicler put it, “certain seductive señoritas,” when the posse approached from the north. Morse and posseman Theodore Winchell, a former policeman, dismounted at a corral behind the López adobe while Sheriff Harris and the rest of the posse rode on toward the other adobes.

Morse, certain they would ultimately find Soto at the Alvarado adobe, left his Model 1866 Winchester carbine in its saddle scabbard. His plan was to arrest the occupants of the López adobe, place them under guard and then rejoin the rest of the posse for the raid on the Alvarado place. Spotting a vaquero in the corral, Morse asked him for a drink of water. The unsuspecting man led the two officers around to the front door of the adobe. When Morse stepped inside, he got the shock of his life.

Soto was seated at a table directly in front of him, surrounded by male and female friends. Among the latter was Bartolo Sepulveda. Morse instinctively jerked his six-gun, a .44 Smith & Wesson American, and barked, “Manos arriba!” (“Hands up!”). Winchell stood beside him, clutching a shotgun.

Soto did not move. Concealed beneath his long blue soldier’s overcoat was a pair of holstered revolvers.

“Manos arriba!” Morse repeated, but Soto merely glared at the Anglo lawmen. Morse gave the order a third time, warning he would open fire if Soto did not comply. The desperado didn’t twitch. The sheriff yanked out a pair of handcuffs.

“Put them on him, Winchell.”

The posseman took the handcuffs, but he was frozen in fear.

“Put them on him!” Morse snapped again, but still Winchell didn’t move.

“Then cover him with your shotgun while I do it!”

Winchell took a long look at the scowling bandido, then whirled and fled out the door. At that a burly Mexican woman seized Morse’s pistol arm, while one of Soto’s compadres grabbed his other arm, each yelling, “No tiré en la casa!” (“Don’t shoot in the house!”).

Soto leaped to his feet and tore open his coat to pull his pistols. Before he could draw, however, Morse jerked his gun hand free and fired, ripping Soto’s hat from his head. The sheriff then broke from his captors and ran outside, followed by Soto. The outlaw let loose a torrent of curses as he chased the sheriff to the rear of the adobe. Harris made a dead run for his horse, hoping to reach his Winchester. Over his shoulder he saw Soto, just yards away, raise one of his percussion Colts high in the air. (Gunmen of the era were in the habit of pointing their pistols up before shooting, thus allowing any spent percussion caps to fall free and not jam the cylinder.) As Soto lowered the weapon and fired, Morse dove to the ground, dodging the bullet.

The sheriff fired back, then sprang to his feet and ran toward his horse. Again Soto leaped forward, raised his pistol and fired, and again Morse dropped to the ground as the bullet whined above him. Three more times this happened. Hearing the shots, Sheriff Harris galloped back to the adobe and witnessed the gunplay. Each time Morse dropped, Harris thought he’d been killed. But each time the plucky sheriff jumped to his feet, returned fire and kept running to his mount. Morse’s last shot struck the cylinder of Soto’s raised pistol, jamming the gun and slamming the barrel back into the outlaw’s face, stunning him.

Recognizing his predicament, Soto raced back into the adobe even as Morse cleared his Winchester from its scabbard. Moments later Soto and Sepulveda burst from the adobe. They had switched coats and hats. As they ran toward a picketed horse 30 yards distant, Sheriff Harris dismounted at Morse’s side and took aim at Sepulveda with his Spencer rifle. Recognizing the outlaws’ ruse, Morse knocked his fellow sheriff’s barrel skyward, sparing Sepulveda’s life. Soto was the man he wanted.

Just as Soto reached the picketed mount, the spooked horse broke loose and galloped off. Without breaking his stride, the desperado turned and ran toward another horse, picketed in front of the adobe some 200 yards away.

“For God’s sake, Juan, throw down your pistols!” Morse shouted. “There has been shooting enough!”

Paying no heed, Soto kept running, Sepulveda close behind him. As Soto increased his lead to 150 yards, Morse took careful aim and fired. The .44 ball tore through the outlaw’s right shoulder. Realizing he could not escape, the enraged bandit wheeled and charged headlong at Morse, a revolver in each hand. At a range of more than 100 yards Morse again squeezed the trigger. The heavy slug struck Soto just above the eyes, tearing off the top of his head.

Juan Soto dropped dead on the spring grass, thus ending a classic outlaw-lawman gunfight, perhaps the most storied in California history. Soto had died as he lived, guns in his hands, contemptuous of Anglo authority to his last breath. WW

John Boessenecker, a San Francisco attorney and former police officer, is a frequent Wild West contributor and the author of such award-winning books as Bandido: The Life and Times of Tiburcio Vásquez (2010) and Lawman: The Life and Times of Harry Morse, 1835–1912 (1998), which are suggested for further reading. See Reviews for Boessenecker’s rundown of some of the most interesting books and movies about California outlaws.