In late November 1862, Confederate General Braxton Bragg settled his newly christened Army of Tennessee into winter quarters at Murfreesboro, Tenn. He hoped his Union opponent Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans would suspend operations for the season as well. December would be essentially a raiding month for the Rebels, as John Hunt Morgan embarked on a pair of daring incursions into Kentucky and Nathan Bedford Forrest created havoc for the Federals in western Tennessee. Rosecrans, however, had no intention of staying put. The day after Christmas, his Army of the Cumberland left the cozy confines of Nashville and headed straight for Bragg.

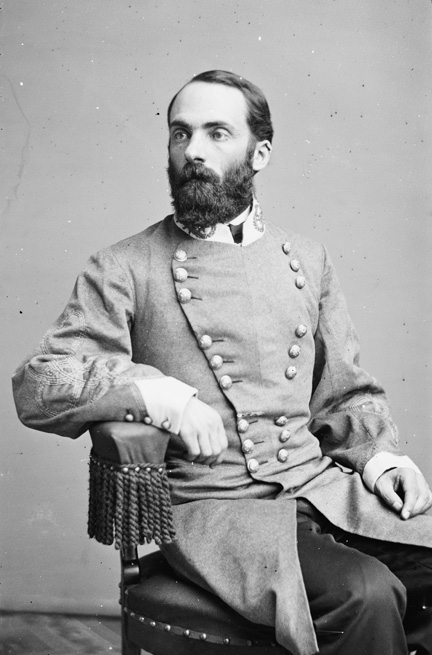

The ensuing Battle of Stones River, fought from December 31 to January 2, would end in a strategic victory for Rosecrans that boosted Union morale in the wake of the December setback at Fredericksburg. But even in defeat, the Army of Tennessee’s cavalry—and its leader, Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler—had performed admirably, and would remain an essential part of Confederate hopes in the West for the remainder of the war.

While John Hunt Morgan operated in Kentucky and Nathan Bedford Forrest raided in western Tennessee, Joe Wheeler remained with Braxton Bragg, scouting inside enemy lines, establishing outposts on the roads between Murfreesboro and Nashville, and interrogating prisoners in the hope of keeping abreast of William Rosecrans’ intentions. Wheeler’s activities between late November and mid-December earned Bragg’s gratitude and praise. When the cavalry leader was wounded while accompanying one of his patrols, however, his commander warned him that “you expose yourself too recklessly in affairs of this character.”

But Wheeler’s industry and efficiency, and his willingness to serve Bragg in any capacity, earned rewards. Soon after the army reached Murfreesboro, Wheeler’s sphere of authority expanded with the addition of three regiments formerly part of Lt. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith’s command. Weeks later, he was joined by a small brigade under Kentucky-born Colonel Abraham Buford, a Mexican War veteran and former captain in the 1st U.S. Dragoons. With Bragg’s hearty endorsement, Wheeler was appointed a brigadier general, to rank from October 30.

Although held in high regard by his superior, Wheeler was not universally admired. As a leader of cavalry, Forrest never considered Wheeler his equal, let alone his superior. He considered him plodding, unimaginative, textbook-bound and too willing to do the bidding of infantry commanders. Morgan was careful to show Wheeler greater deference, but in private he too was critical. Brigadier General Basil Duke, Morgan’s brother-in-law and second-in-command, summed up Morgan’s views when he commented after the war that Wheeler had risen to high command “more on account of the dislike entertained by [Bragg] to certain other officers, than because of the partiality he felt for him. The reputation of this officer, although deservedly high, hardly entitled him to command some of the men who were ordered to report to him.”

Wheeler undoubtedly was aware of how these subordinates perceived him. He was determined to prove Bragg right in elevating him above them, and found an opportunity much sooner than he expected. Like Bragg, Wheeler assumed Rosecrans would remain in his warm and comfortable citadel at least until spring. But before November was over, Wheeler was surprised to find himself skirmishing regularly, sometimes several times a day, with Yankee cavalry and infantry out of Nashville.

But even when Wheeler offered timely assessments of enemy movements, they were not always heeded. By mid-December he came to suspect that, contrary to expectations, Rosecrans planned an offensive. But Bragg saw the inordinate amount of activity inside Nashville as a sign that Rosecrans was on the verge of evacuating the capital. Hoping for confirmation, Bragg ordered Wheeler on December 20 to “press forward…and ascertain the true condition of things.” Wheeler obeyed, but learned nothing that suggested a Union withdrawal.

The day after Christmas, Wheeler was proved right. That morning Rosecrans’ army—some 45,000 infantry and artillery, screened by 4,000 cavalry under Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley—advanced from Nashville toward Murfreesboro. Wheeler, supervising Bragg’s first line of defense, prepared to meet the enemy at the head of his own brigade. The brigade’s picket line had stretched from a point east of Stones River to the Nashville suburb of Brentwood. The pickets of Wharton’s brigade, west of Wheeler’s, held a line between Nolensville and Franklin, while Brig. Gen. John Pegram’s pickets covered the approach to Lebanon. Wheeler’s job was hindered because he directly commanded one brigade but led two others remotely, a particularly unwieldy arrangement for a cavalry commander.

Rudely awakened to Rosecrans’ plans, Bragg placed infantry within supporting distance of each of Wheeler’s brigades. Even before the foot soldiers reached him, Wheeler countered General Stanley’s advance on the Nashville Pike. He soon found himself opposed not only by horse soldiers but by the advance element of an infantry corps commanded by a familiar opponent, Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden, a Kentuckian who had sided with the Union.

The Federals pressed Wheeler throughout the morning, but he managed to hold up the offensive for nearly an hour. When one of Crittenden’s brigades finally fought its way to the front, threatening to outflank him, Wheeler deftly withdrew south of Stewart’s Creek and frustrated Crittenden’s attempts to ford it. Wheeler and his infantry supports spent the night in La Vergne, an objective Rosecrans had expected to seize that afternoon.

Called to Murfreesboro to take part in a council of war, Wheeler found that Bragg needed time to mass his army and fortify a defensive position. Wheeler reportedly promised he could keep the enemy away from Murfreesboro for several days.

Over the next three days, he skillfully used the same fight-and-fall-back technique he had mastered during the retreat from Perryville in October. He stymied not only Crittenden’s men on the turnpike but also helped Pegram and Brig. Gen. John Wharton employ similar delaying tactics.

Events had proceeded just as Bragg hoped. Rosecrans’ advance was slowed to a crawl, and Wheeler’s troopers, supported by infantry, delivered an effective fire that killed and wounded scores of Federals while “meeting but very slight losses ourselves.” Wheeler continued to block Stanley’s and Crittenden’s paths throughout the 27th. The weather helped, particularly a steady, frigid rain that turned the roads to ice-coated slush.

Wheeler’s only concern was the condition of Wharton’s command, which faced Rosecrans’ right wing. The Federals drove Wharton from one position to another, but usually in good order. On the 28th, Wheeler met some initial pressure that abruptly subsided when Crittenden chose to remain left of Stewart’s Creek as Alexander McCook’s and George H. Thomas’ Union troops moved into position. Wheeler welcomed the Yankees’ deliberate pace, since Bragg’s infantry was recalled to Murfreesboro, leaving the cavalry to fend for itself.

The Federals finally made progress on the 29th. Crittenden’s wing advanced briskly under cover of a barrage from cannons on a ridge overlooking Stewart’s Creek. Wheeler replied with shot and shell from an Arkansas battery, but failed to detect small bands of foot soldiers crossing the creek. The Federal infantry quickly secured the far bank, permitting comrades to cross in large numbers, and then marched well inside Wheeler’s lines before halting north of Overall Creek, less than a mile from Bragg’s main line northwest of Murfreesboro.

This penetration forced Wheeler to fall back yet again, but having held back the blue tide for three days, he had accomplished his mission. He coolly led his brigade across Stones River and up the Lebanon Pike, toward the Confederate right flank. As night approached, he aligned his troopers about a mile ahead of John Breckinridge’s division, joined by Pegram’s brigade east of the Lebanon Pike. Wharton’s command, meanwhile, covered the front, flanks and rear of General William Hardee’s corps.

Wheeler’s cavalry had bought Bragg needed time. The Confederate force closely matched Rosecrans’, and Bragg grew confident he could go on the offensive.

Bragg had weakened his army’s mobility by sending Forrest and Morgan on remote assignments, and on the raw and rainy morning of December 30 he ordered Wheeler to lead his brigade up the Lebanon Pike toward the village of Jefferson. The move carried Wheeler around the Army of the Cumberland’s left flank, into its rear, where he was to strike the wagon trains then rolling between Rosecrans’ army and Nashville.

Bragg hoped this would distract Rosecrans as the Confederates attacked his right flank. In Wheeler’s absence, Wharton’s brigade would guard Bragg’s left and assist in the opening assault, while Pegram’s brigade, the smallest of the three, would picket the army’s right and rear. Abraham Buford’s even smaller brigade would cover the army’s far rear at McMinnville, about 50 miles southeast of Murfreesboro.

Wheeler’s expedition achieved dramatic results, but whether it made a material contribution to Bragg’s strategy is unclear. After penetrating enemy lines on the morning of the 30th, Wheeler turned off the turnpike and headed toward Nashville. Detouring to the south of Jefferson, reported to be heavily defended, the rain-drenched column forded Stones River near Neal’s Mills, circled north until regaining the Nashville Pike and resumed its westward surge. Wheeler soon came upon a 60-wagon supply train. His raiders attacked the train, drove off its guards, burned a couple dozen wagons and shot or sabered their teams.

The Federal guards raced toward Jefferson, spreading an alarm. In quick time, two infantry regiments under Colonel John C. Starkweather hustled to curtail Wheeler’s depredations. “Fightin’ Joe” held them at arm’s length with dismounted skirmishers while the rest of his brigade galloped west. Bragg had stressed that the raiders not fight unless absolutely necessary.

Moving on to the railroad village of La Vergne, the column relieved several foraging parties of their spoils, also taking prisoners. Outside the depot, Wheeler discovered General McCook’s enormous supply train. He deployed carefully before attacking the wagons from three sides. “We dashed in,” a trooper recalled, “four or five regiments, at full speed, fired a few shots and we had possession of an army train of over three hundred wagons, richly laden with quartermaster’s and commissary stores.”

Realizing he was far behind enemy lines and suspecting that with a battle brewing Bragg would want his cavalry in hand, Wheeler turned south. Near Stewartsburg, his rear guard was assailed by Colonel Moses Walker’s Ohio infantry brigade. After what one raider called “liberal application of the spur for two hours,” the raiders not only outdistanced the Ohioans but overtook a third supply column hauling rations and materiel.

Early in the afternoon on the 31st, Wheeler hooked up with Hardee on the army’s left flank. His men had circumnavigated Rosecrans, damaging or destroying upward of 500 supply wagons and taking more than 600 prisoners. They rejoined Bragg to the accompaniment of artillery blasts and the rattle of small arms. Hardee’s infantry, screened by Wharton’s cavalrymen, had taken McCook by surprise, displacing the Union right flank.

A few hours after reaching Wilkinson’s Cross Roads, Wheeler heard the Union right was teetering on collapse. Displaced Yankees were streaming north toward the Franklin Pike apparently in utter rout. Other components of Rosecrans’ command, however, would join McCook’s survivors at a new point parallel to the turnpike. They would hold their ground with fanatical tenacity, and would summon the power and nerve to mount a counterattack.

Wheeler expected to be sent directly to the firing lines, and he wasn’t disappointed. The infantry would conduct most of the fighting on December 31, but Bragg ordered Wheeler, accompanied by Buford’s brigade, to move north and strike the Nashville Pike west of Overall Creek. At the same time, Wharton was to attack a supply column reportedly moving up the pike on the other side of the stream. Pegram’s troopers would be left with the army to provide support as needed.

Fording Overall Creek under long-range infantry fire, Wheeler advanced toward the turnpike. Just shy of the road, a large portion of Thomas’ corps, covered by Stanley’s horsemen and anchored by artillery, loomed in Wheeler’s front. The cannons poured a salvo into the head of Buford’s Kentuckians, inflicting a number of casualties and forcing Buford to withdraw. Impressed by the strength of the opposition and doubtful that

Wharton was keeping pace on the other side of the creek, Wheeler instructed Buford to fall back to Wilkinson’s Cross Roads.

Wheeler soon discovered Yankees near Asbury Church, a Methodist meetinghouse east of Overall Creek, and decided to take them on. Stanley’s skirmishers detected Wheeler’s approach, however, and the Union leader sent forward two regiments that kept up a brisk fire and brought Wheeler’s column to a halt.

Stanley then withdrew to a more defensible position. Wheeler pursued and prepared to attack the Federals after they deployed behind a wooded ridge next to the Nashville Pike. Wheeler hoped to strike not only Stanley’s center but also his exposed flanks. But before he could get into position, detachments from three Federal regiments, brandishing pistols and sabers, charged down the ridge. The unexpected assault caught Wheeler’s force in mid-movement and sent it scrambling to the rear in disorder. By the time the Rebels had recovered their composure, the sun was about to set. Wheeler returned to Wilkinson’s Cross Roads and bivouacked.

Some historians have criticized Wheeler’s operations of December 30-31. Thomas Connelly is particularly hard on him, claiming Bragg ordered Wheeler to attack the Union rear but Wheeler went off on another expedition, on which he “accomplished nothing and was beaten back by Federal cavalry.” But there is no record Bragg gave Wheeler such orders. Bragg, in fact, declared that throughout the 31st, all of his cavalry units “most ably, gallantly, and successfully performed” their assigned duties.

The two armies paused for breath on January 1, gathering up the strength and will to resume the slaughter the next day. At this point, it seemed the Army of Tennessee had won a decisive victory, having driven Rosecrans back more than three miles. The Yankees barely clung to their new position, but they had been helped from defeat by a couple of major Confederate blunders.

Bragg’s cavalry was partly to blame. Mainly because of a lack of real-time intelligence, Breckinridge had not realized the force that had assaulted his position had been withdrawn. Convinced his posture remained precarious, Breckinridge refused a request to send two brigades across Stones River to reinforce Bragg’s attack on the Union right. When Bragg later ordered him to advance, Breckinridge was surprised to find no enemy in his path. But he was quickly recalled when John Pegram sent Bragg an erroneous report that an enemy column was moving toward the army’s rear via the Lebanon Turnpike. Breckinridge’s absence diluted the impact of Bragg’s offensive and enabled Rosecrans to hold on.

Wheeler returned to his raiding mission on January 1, as Bragg hoped another, stronger blow to the enemy’s communication lines would force a retreat. But Bragg guessed wrong, leaving himself open to criticism that he had once again sent his mounted arm away when needed most.

On that bitter cold morning, Wheeler led a column north toward the point where Stewart’s Creek crossed the Nashville Pike, which he thought was lightly guarded. He instead discovered the countryside was alive with Yankee cavalry. He fell back and veered west toward La Vergne, soon overtaking another 300-wagon supply train. Wheeler had Buford’s men attack the train while Wharton was set to wreck the depot at La Vergne.

Wharton was repulsed before he could reach the depot and headed back to rejoin Wheeler, whose men had captured part of the huge Union supply train. Wheeler was galloping hard after the train’s main body as it continued toward Nashville. After several miles, the raiders finally forced their quarry to halt.

Wheeler, however, found the train defended by several regiments of horsemen under one of Stanley’s more combative subordinates, Colonel Lewis Zahm. The dismounted Yankees dug in and put up a formidable defense. Unwilling to be tied down, Wheeler left half his force to occupy the enemy and led the rest toward the head of the train. His attempt to stop the entire column failed, for Zahm was strong enough to overcome the delaying action, remount his men and hasten after Wheeler. Zahm also foiled two attempts by Wheeler to circle around him and attack the train from a different angle.

Wheeler’s repulse ended his efforts to wreak havoc on Rosecrans’ communications. It also gave the lie to Wheeler’s boast that he had “captured and destroyed a large number of wagons and stores.” No more than a dozen vehicles, which had broken down and become defenseless, had fallen into his clutches this day.

Discouraged, Wheeler broke contact with Zahm, fell back and, after linking with an equally frustrated Wharton, withdrew to Overall Creek. Arriving at 2 a.m. January 2, he placed Buford’s brigade in camp west of the stream while he and Wharton crossed to bivouac along the Wilkinson Pike. Making contact with army headquarters, Wheeler relayed his belief that by all indications the Army of the Cumberland was digging in for a fight to the finish. The previous evening, in fact, Rosecrans had conferred with his generals to determine whether to remain on the field or withdraw. Although some subordinates counseled retreat, fearing the army was spent, its commander finally chose to stay and slug it out.

Rosecrans’ decision proved to be one of the most important of his military career. The fighting on January 2, during which he maintained a defensive posture, did not go well for the Confederates. Bragg ordered Breckinridge to cross Stones River, occupy high ground and enfilade the Federals’ new position. Breckinridge feared his objective had been heavily reinforced; Bragg forced him to attack anyway. Crossing the river in mid-afternoon, Breckinridge broke through the line held by Brig. Gen. Horatio P. Van Cleve’s division, but as his men descended the captured ridge, they were savaged by fire from 50 or so cannons as well as a spirited counterattack that cost them 40 percent casualties.

After Breckenridge was driven back to the starting point of his assault, Bragg gave up hope of landing a finishing blow. Though he had taken a grievous toll on his enemy, he had suffered almost as heavily. When his equally chastened corps commanders advised retreat, Bragg gave in to the same faintheartedness he had displayed at Perryville. Early on January 3, he called Joe Wheeler to his side and assigned him an all-too-familiar mission: covering the departure of an army from a battlefield on which it had not been defeated and from which it had not been driven.

Adapted from Cavalry of the Heartland: The Mounted Forces of the Army of Tennessee by Edward G. Longacre. Copyright 2009 by Edward G. Longacre. Published by arrangement with Westholme Publishing, LLC, Yardley, Pa.