As Hitler systematically seized power throughout the 1930s in Germany and began instituting his policies of persecution and murder, tens of thousands of Jewish refugees desperate to escape were trapped in Europe, doomed by Nazi machinations and the American the visa system.

“It takes months and months to grant the visas,” Rep. Emanuel Celler (D-N.Y.) chided while speaking on the House floor in 1943. “And then it usually applies to a corpse.”

Though manipulation of the visa system led to predictably tragic results, many Jewish-German scholars were spared thanks to the willingness of historically Black colleges and universities offer them jobs, even as other American institutions of higher learning turned them away.

Jewish citizens of Germany and its occupied areas increasingly sought refuge in America as Nazi targeting of them grew increasingly active.

The U.S. 1924 quota law allowed up to 25,957 immigration visas for those born in Germany. According the United States Holocaust Museum, in 1933 only 1,241 Germans were issued visas – just 5 percent of the quota limit. Meanwhile, more than 82,000 people remained were on the waiting list. Between 1934 and 1937 an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 Germans were on the waiting list. Most were Jewish. Only 27 percent of the quota was filled. Despite being aware of ongoing Nazi atrocities, this did not spur a federal response.

In 1938, President Franklin Roosevelt upped the quotas, making 27,370 visas available each year for those seeking to emigrate from Germany and Austria. In 1939 the maximum number of visas was issued, yet nearly 10 times that number of people remained on the list.

In 1941, after the U.S. entered the war, the State Department cancelled the waiting list and only those German refugees outside of Nazi territory were allowed U.S. visas. After that, the average plummeted to just 8 percent.

The process of obtaining a visa itself was challenging. Jewish citizens of Germany each needed an American financial sponsor who promised, to take responsibility for the refugee upon arrival. That was just one of the many onerous obstacles that refugees faced.

The low immigration numbers, however, would have been even smaller without the backing of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in the United States.

In his book Intellectuals in Exile: Refugee Scholars and the New School for Social Research, Claus Dieter Krohn recounts how American colleges in the 1930s were reluctant to employ scholars fleeing Nazi Germany. John Herz, a German-born Jew had earned his doctoral degree from Cologne University in Germany, studying international law and political theory. As a refugee in the U.S., Herz was hired as a substitute teacher for the summer at a college in Connecticut, but was told that they “wouldn’t employ [him] full time after that. One of them told [him] later – rather shamefully – that [him] being a Jew in addition to being a refugee was the reason.”

However, “in an important exception,” Krohn writes, “many of us young refugee scholars found our first teaching opportunities at black colleges.” Herz joined the staff of Howard University in 1941.

Of the nearly 1,200 Jewish academics that came to the United States, 53 Jewish academics landed jobs at Black colleges in the segregated South.

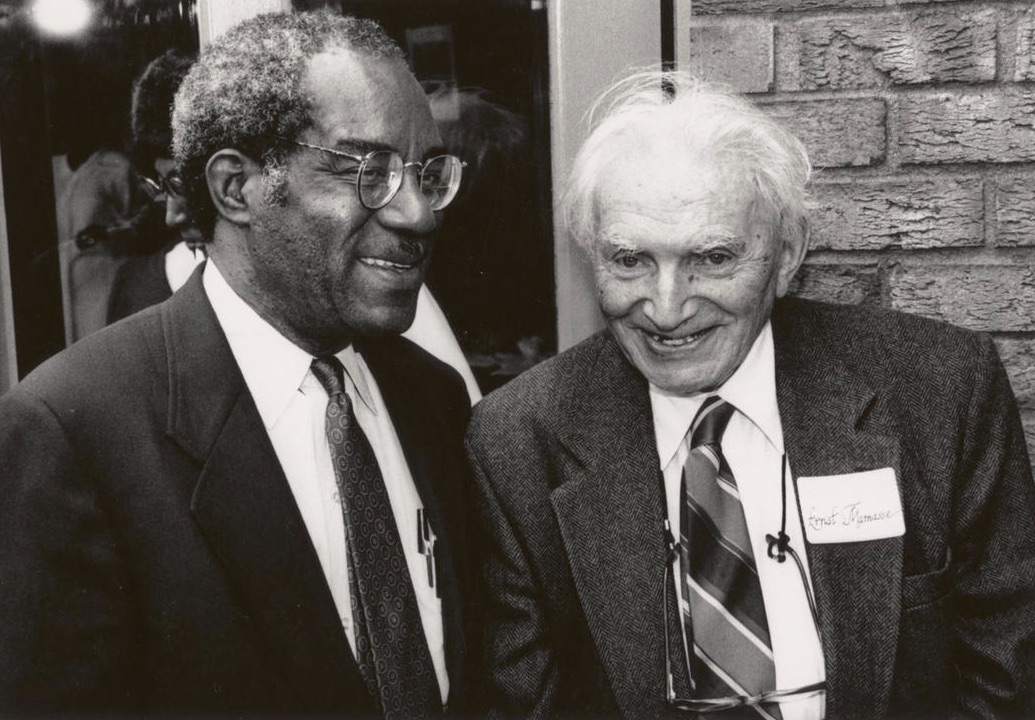

This was a different world,” said Ernst Manasse in the documentary film From Swastika to Jim Crow. Manasse arrived at the North Carolina Central University in Durham in 1939 and taught there for 34 years. “It was a little country college, but it was my salvation.”

Manasse was a philosopher who left Germany in 1935 after Nazis blocked his father’s funeral procession because it included Jews. After a brief time in Italy and England, Manasse was able to collect an affidavit of support from a reluctant uncle in America. However, after a year of searching for an academic position his visa was set to expire. James Shepard, president at NCCU, offered him a position, qualifying Manasse for a work visa and ultimately saving his life. “If I had not found a refuge at that time,” Manasse later reflected, “I would have been arrested, deported to a Nazi concentration camp, tortured and eventually killed.”

Shepard would go on to hire three more German scholars and Manasse remained on the NCCU faculty until his retirement in 1973.

For many of the Jewish professors it was the first time ever meeting a Black person, and the students themselves often had little or no prior exposure to Jews. However, Krohn writes that mutual sympathy arose between the Jewish professors and their Black students – united as victims of persecution and discrimination. “Racial segregation reminded me a lot of Nazi Germany, except that I wasn’t a victim, the black population was,” said Georg Iggers, a German Jewish refugee who taught history at Philander Smith College.

For some students going to school in the South, there emerged a dichotomy between sympathy and resentment, resentment that America was fighting Nazism overseas while Jim Crow and discrimination reigned at home. One of Manasse’s former student’s, Eugene Eaves, recalled that the professor, “found it strange that he had come to the United States because he was oppressed and yet here he was a member – ethnically – of the group that oppressed the groups he was teaching.” Yet through the auspices of HBCUs, these relationships thrived.

It was under these unique and tragic circumstances that brought Jewish refugees and Black Americans together. Motivated by humanitarianism, many ordinary Americans at HBCUs did the extraordinary, bypassing the official gatekeepers of the State Department, and saving the lives of thousands.