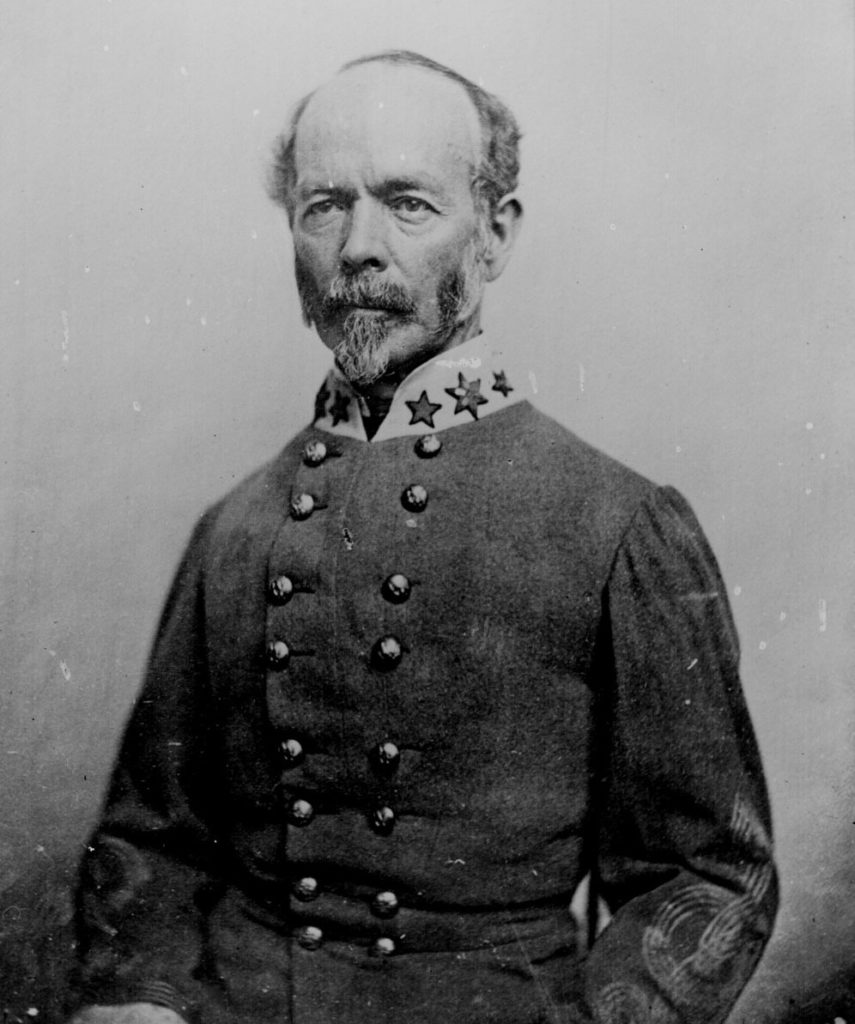

Outmanned, disorganized and disheartened, the Confederates could do little more than harass Gen. William T. Sherman’s Federals as they swarmed through the Carolinas in February and March of 1865. But as he met with his commanders on March 18 just southwest of Bentonville, N.C., Sherman conceded he wasn’t ready to count out his familiar old adversary, Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, just yet. Engagements at Monroe’s Crossroads and Averasboro in recent days had shown that the Rebels still had a pulse and were doing what they could to stop the Federal juggernaut. Despite the odds, Johnston remained optimistic as long as he could keep Sherman’s army away from Ulysses S. Grant’s, currently pinned down opposite Robert E. Lee at Petersburg, Va.

The two wings of Sherman’s 60,000-man force had marched north on parallel paths since departing Savannah, Ga., on February 1. Now, eight days after crossing into North Carolina, they were about 25 miles from Sherman’s ultimate destination, the railroad town of Goldsboro. On the morning of March 19, Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s Left Wing would continue marching up the Goldsboro Road while Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s Right Wing proceeded along a separate road to the south. If all went as planned, they would meet that afternoon at Cox’s Bridge—roughly 12 miles from Goldsboro—and then cross the Neuse River for the stretch run. The Federal forces of Maj. Gens. Alfred Terry and John Schofield, marching from Wilmington and New Bern, were to join them in Goldsboro.

Johnston was still unsure whether the Federals were heading to Goldsboro or the state capital of Raleigh, so he established his headquarters in between at Smithfield and scrambled to consolidate his command. The Army of the South had been cobbled together from the remnants of the Army of Tennessee; a 12,000-man force under Lt. Gen. William Hardee; Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton’s Cavalry Command; and Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Department of North Carolina.

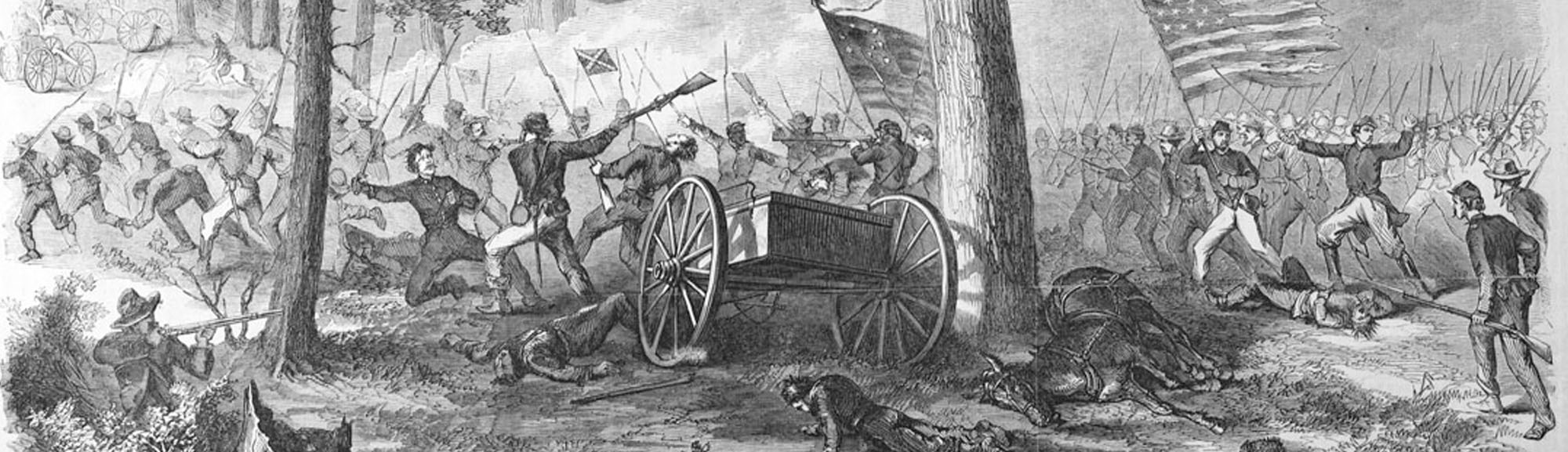

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Battle of Averasboro on March 15-16 had given the Rebels some hope. By attacking and nearly overcoming Slocum’s isolated wing, Hardee showed that the Federals were not invincible. Perhaps another strike on one of Sherman’s isolated wings, this time by a consolidated unit fighting on ground of its own choosing, would deliver the victory Johnston desperately needed.

Convinced Goldsboro was Sherman’s true target, Hampton established a defensive position around the Cole Farm near Bentonville and prepared to intercept Slocum’s wing as it advanced. He vowed to hold Slocum back with his cavalry while the rest of Johnston’s army rushed to Bentonville. Bragg and three Army of Tennessee corps arrived overnight on March 18-19.

Maj. Gen Jefferson C. Davis, commanding Slocum’s XIV Corps, sensed the enemy buildup and cautioned Sherman that he expected to face more than just “the usual cavalry opposition.” Sherman gently chided him, “No Jeff; there is nothing there but…cavalry. Brush them out of the way.”

Leading the Union push was Brig. Gen. William Carlin’s division. Carlin’s men soon learned, as Davis had warned, that a larger force was indeed waiting when they came under intense artillery fire at the Cole Farm and had to hastily erect a breastwork in an open field. To his credit, Slocum acted decisively once he learned the reality of the situation. He rushed Maj. Gen. Alpheus Williams’ XX Corps to the front, realigned his wing into a defensive formation and quickly got word to Sherman to send reinforcements.

By 2 p.m. the entire Confederate force was on the field, and at 2:45 Hardee sent the Army of Tennessee and William Taliaferro’s Division forward. It would be the last great advance of a Rebel army during the war and was initially successful, putting the finishing touches on the rout of Carlin’s division. But Bragg, ordered to move in tandem with the Army of Tennessee, stayed in place, which allowed Gen. James Morgan to strengthen his division’s position. When Bragg finally moved, Benjamin Fearing’s brigade was ordered to make a counterattack. Fearing’s men were soon overwhelmed, but a determined stand by the 125th Illinois bought some time. The first day’s fighting ended at sunset when the Federals stopped a strike by Col. Alfred Rhett’s Brigade. Though stunned, Slocum had earned a tactical victory that day by holding his position, and with reinforcements on the way, the outlook was promising.

The sides resorted mainly to skirmishing on March 20. Aware that Union reinforcements were coming, Johnston extended his left flank and ordered Bragg to realign his division north of Goldsboro Road. Slocum, meanwhile, moved his corps forward to occupy the previous day’s battlefield.

Early on March 21, Slocum sent out skirmishers to determine the Confederate presence. About mid-morning, Union Maj. Gen. Joseph Mower received permission to lead a “reconnaissance” around the Rebel left and nearly captured the bridge over Mill Creek, Johnston’s lone retreat route to Smithfield. A counterattack led by Hardee drove Mower back, but as “Fighting Joe” began planning a second attack, Sherman ordered him to return to the main Union lines. Had Mower succeeded in securing the bridge, Johnston would have had little choice but to surrender right there.

Bentonville was the Rebels’ last gasp. Johnston retreated to Smithfield that night, and the Federals continued on to Goldsboro. Once Lee’s army fell at Petersburg and then Appomattox, Johnston agreed that further resistance was futile. Near Durham, N.C., on April 26, he surrendered his army to Sherman. The war was all but over.

Chris Howland is the editor of America’s Civil War.

Originally published in the March 2015 issue of America’s Civil War. To subscribe, click here.