Dwight Hal Johnson had no dreams of being a hero. In his youth, the large, strapping boy had a fighter’s body but a peaceful spirit. Johnson grew up in the deteriorating Corktown neighborhood of Detroit with his single mother and younger brother. Bullies often chased him home. “Don’t you fight, honey,” his mother told him, “and don’t let them catch you.” He didn’t.

Drafted at age 19, Johnson arrived in Vietnam in February 1967. He was a tank driver in Company B, 1st Battalion, 69th Armor Regiment, 4th Infantry Division. By January, Johnson, a specialist 5, had orders to return home in two weeks. He had never seen combat and was content with that. Johnson’s destiny changed on Jan. 14, 1968, when he was transferred from his usual tank to one whose driver was sick.

The next day, four M48 Patton tanks of Johnson’s company raced down a road toward Dak To in the Central Highlands. Suddenly enemy rockets slammed into two tanks. Johnson raised himself from the hatch of his M48 to return fire with its .50-caliber machine gun as waves of enemy infantry swarmed the remaining tanks.

He saw his former tank about 60 feet away—and his buddies for the past 11 months trapped inside the burning hulk. Leaping from his tank, Johnson ran through gunfire to save their lives, ignoring the pleas of Stan Enders, a gunner in his new crew, who shouted, “Don’t go!” Johnson pulled out one man, who was burning but still alive, and dragged him to safety before the tank exploded, killing the rest of the crew.

When Johnson saw the burning bodies, something inside snapped. Rushing back to his tank, he seized a submachine gun and charged into the ambush, attacking first with automatic fire, then with his pistol. Coming face to face with an enemy soldier wielding an AK-47 rifle, Johnson pulled the trigger only to find his pistol empty, so he killed the man with the stock of his empty submachine gun.

Returning to his tank, Johnson manned the externally mounted .50-caliber machine gun and remained there until his adversaries withdrew. Johnson had fought ferociously for about 30 minutes, and his comrades estimated he had taken out as many as 20 enemy soldiers.

Although the battle ended, an enraged Johnson had to be restrained to prevent him from attacking captured troops. Three doses of morphine were needed to calm him. Placed under restraint, he was evacuated to the hospital in Pleiku.

After the soldier returned home, his friends assumed Johnson had never seen combat. He did not correct them.

Johnson’s day of heroism was a dark, haunting experience he wished he could forget. Constant nightmares were filled with the burned bodies of his dead friends and the face of the enemy soldier he killed at close range.

One bright spot in Johnson’s life was his marriage to his sweetheart and the birth of their son. But he couldn’t find work to help them.

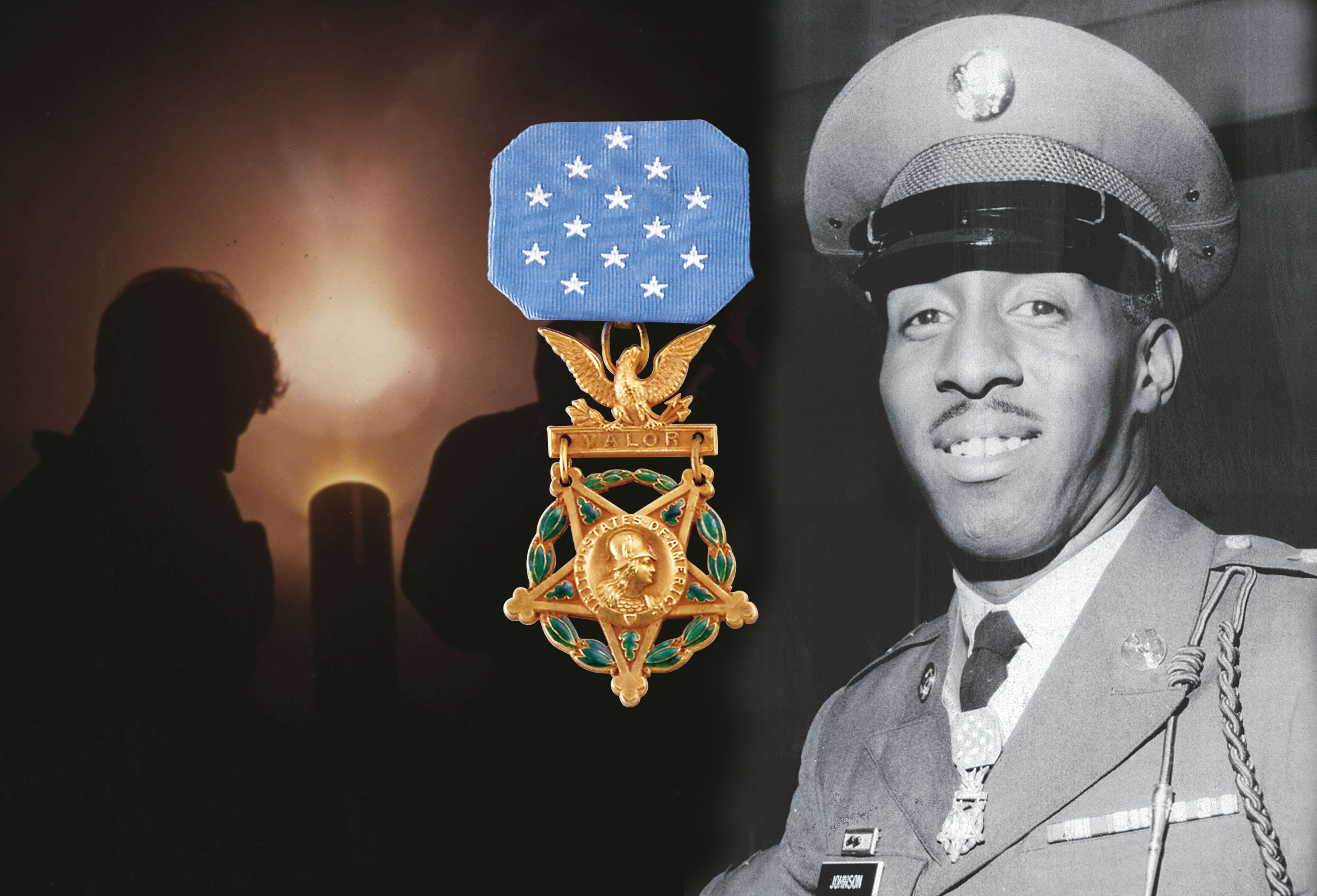

One day, a colonel called from Washington to tell Johnson that he and his family should come to the capital. On Nov. 19, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented Dwight Hal Johnson with the Medal of Honor.

Johnson became a local celebrity and received job offers. Eventually, he returned to the Army and worked as a recruiter in Detroit. Constant nightmares and cold sweats still tormented him, however, and he suffered from severe survivor’s guilt—his tank transfer had saved him from the explosion that killed his former crew members.

Back in Detroit, on the night of April 30, 1971, Johnson walked into a store with a pistol and demanded cash from the register. He fired a round that struck the arm of the store owner, who shot the 23-year-old Medal of Honor recipient four times. Johnson died at the hospital.

Later his mother told a New York Times reporter that she wondered if her son was having suicidal thoughts. The hero of Dak To, who struggled in his battle with post-traumatic stress disorder, was buried with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery. V

Doug Sterner, an Army veteran who served two tours in Vietnam, is curator of the Military Times Hall of Valor database of U.S. valor awards.

This article appeared in the October 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here: