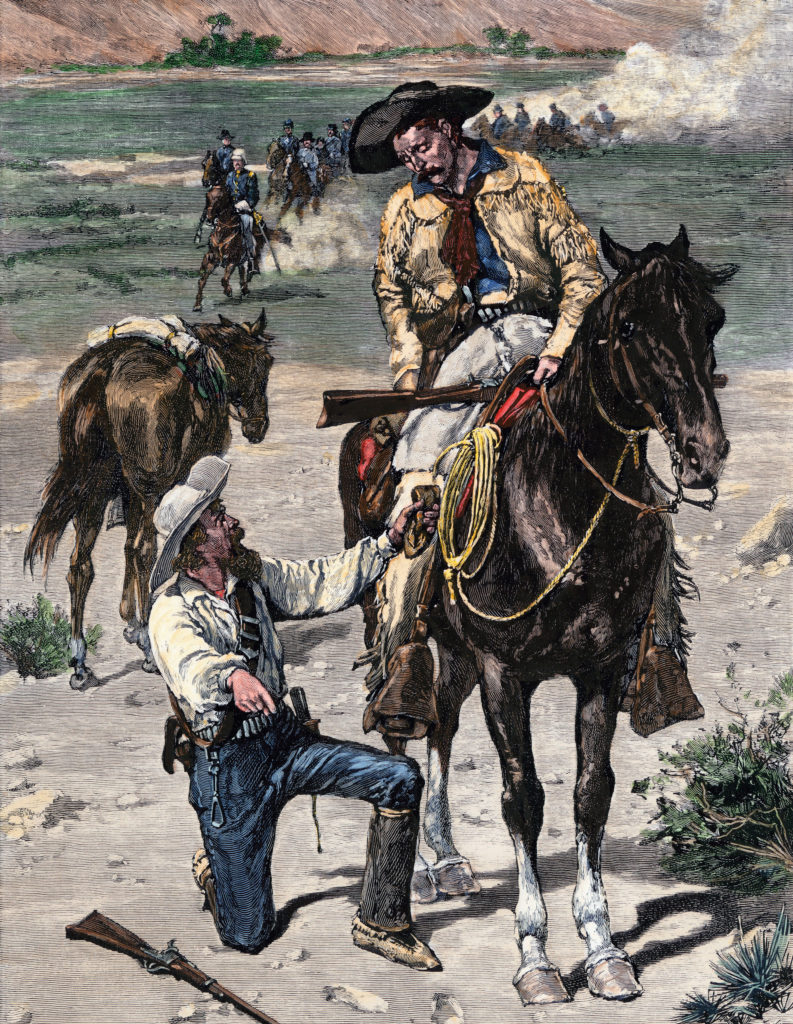

The success of U.S. Army expeditions on the Western frontier depended on many factors. The acumen of the commander was a primary consideration, of course, but the availability of water, accurate maps, adequate supplies, healthy troops and horses, and favorable weather all played a role. In many cases the reliability of information was the indispensable component, making the difference between brilliant success and abject failure, even disgrace. Thus, perhaps no other member of a force was as irreplaceable as an experienced and trusted scout.

In an age without drones, satellite intelligence, telephones or even radios, scouts were the eyes and ears of an army. Field officers depended on the intelligence these hardy denizens of the plains and mountains provided, from approximate distances and descriptions of terrain to the likely behavior of Indian tribes and, foremost, the position of enemy forces.

Western films often depict the Old West scout as a scruffy, buckskin-clad white man, and many real-life scouts fit that description, notably Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, Buffalo Bill Cody and Wild Bill Hickok. But perhaps the most successful scouts were those with one leg in white culture and the other in Indian culture. Half-blood scouts who could move easily between both worlds were much in demand.

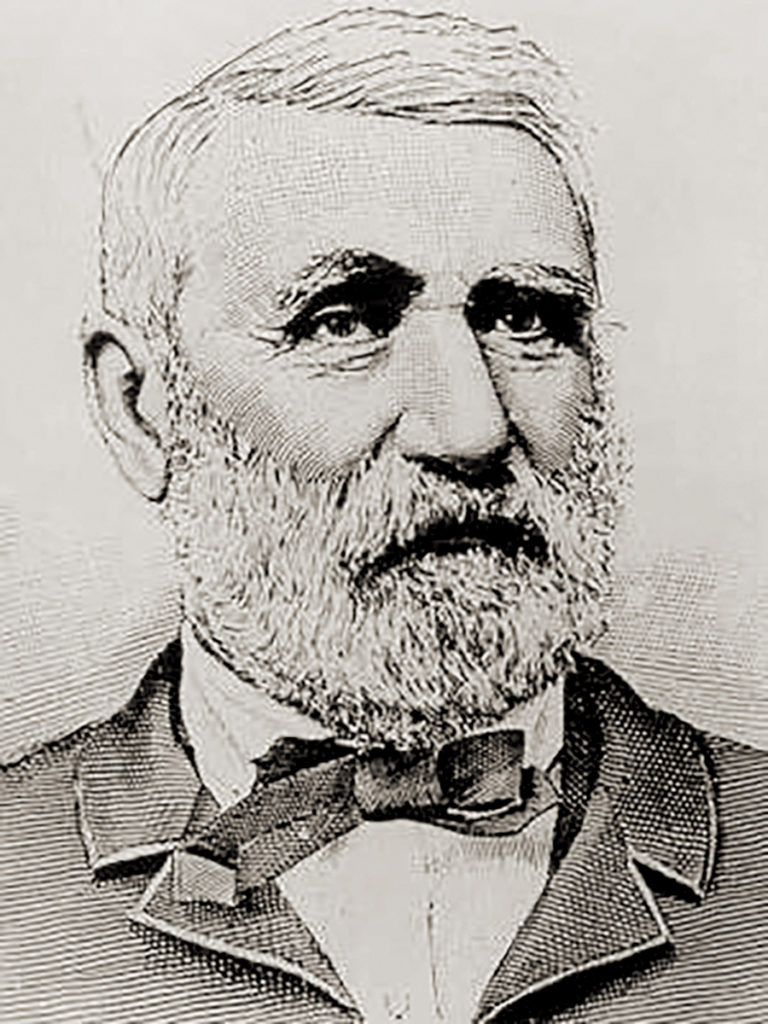

One such member of this small but prized club was Johnnie Bruguier, who was born in 1849 in a cabin built by his father, Théophile, at the confluence of the Missouri and Big Sioux rivers, on the site of present-day Sioux City, Iowa. A onetime trader with the famed American Fur Co., Montreal-born French Canadian Théophile Bruguier had struck out on his own and did a brisk business with the Yankton Sioux. He was also simultaneously married to two Indian wives, a common practice in that time and place. Together they bore him 13 progeny. Johnnie was the third of seven surviving boys. His mother, Dawn, was the second of Théophile’s Indian wives, both of whom were daughters of Yankton Chief War Eagle. Théophile gradually expanded his trade to the military. The family also received substantial land and cash payments stemming from the 1858 Yankton Treaty between the U.S. government and the tribe.

So, while Johnnie grew up on the frontier, it was not in hardscrabble circumstances. Théophile was determined his children receive an excellent education, and his financial acumen enabled him to send them in turn to the College of Christian Brothers in St. Louis, which remains in operation as a prep school. Founded in the 1670s by French priest Jean-Baptiste de la Salle (since recognized by Roman Catholics as the patron saint of teachers), the religious order that ran the college championed La Salle’s innovative teaching practices, thus Johnnie received a cutting-edge education.

Théophile’s first wife, Blazing Cloud, died in 1858, while Dawn died just three years later. In 1862 Théophile took a third wife. This time he chose a white woman, refined St. Louis native Victoria Brunet. Apparently, she was ill-equipped to mother such rambunctious children of the frontier, as Johnnie and his siblings spent increasingly longer periods with relatives of their late mothers on the Yankton Sioux Indian Reservation, in southeastern Dakota Territory.

On Sept. 3, 1863, 13-year-old Johnnie was a passenger aboard the mail coach from Fort Randall, Dakota Territory, returning east to Sioux City on the stage road along the Missouri River. Accompanying him was a soldier he’d befriended, 24-year-old Sergeant Eugene Trask of the 7th Iowa Cavalry Regiment. As usual the sergeant was entertaining the someday scout with tales of Indian battles and massacres, perhaps relating depredations committed during the 1862 Sioux Uprising in nearby southwest Minnesota. (That spring the Army had settled the exiled Santee Sioux from Minnesota on a reservation along the stage road in Dakota Territory.) Suddenly gunshots rang out around the coach, and Trask dropped dead at Johnnie’s side. As the driver reined the horses to a standstill and bolted for his life, four Santees in warpaint rode up to the coach. Recognizing his own peril, young Bruguier spoke to the attackers in their language. Presumably assuming the boy, though light-skinned, must be one of their own, the four raiders let Johnnie be. After rifling through the contents of a trunk, they rode off with the coach’s team.

Perhaps emboldened by his first brush with death, Johnnie pressed to accompany his father’s far-flung trading ventures. He often joined Théophile’s wagon trains as they made their way up the Missouri with trade goods and then returned with expansive loads of furs and buffalo robes that further added to the family coffers. As he gained experience, young Bruguier took on greater responsibilities with the company. But while he might someday have inherited his father’s business empire, Johnnie had other ideas.

Scouting Career

In 1868 the U.S. government negotiated the Treaty of Fort Laramie, establishing the 60-million-acre Great Sioux Reservation in Dakota Territory (west of the Missouri River in present-day South Dakota). Various Indian agencies were established west of the Missouri, and in the fall of 1870 Johnnie’s older brother Charles took a job with the Grand River Agency, near the mouth of the namesake river along the present-day inter-Dakota border. Johnnie joined him there the next summer. Many Sioux, mostly Hunkpapas and Yanktonai (the latter one of the seven subtribes of the Dakotas who spoke the same dialect as the Yanktons), still roamed free, and agency officials had been tasked with turning such “renegades” into “civilized” Indians.

On July 12, 1871, Johnnie signed up as a scout and interpreter for the soldiers assigned to protect the agency. He served in that capacity through March 31, 1872, and the next day hired on with J.C. O’Conner, Grand River’s civilian agent. Johnnie’s little brother Billy took a job with O’Conner that year, as did youngest brother Sam the following June. The Bruguier boys, though serving mainly as interpreters, were jacks-of-all-trades at the agency. During slow periods they hired out for various enterprises, even working at times for local farmers.

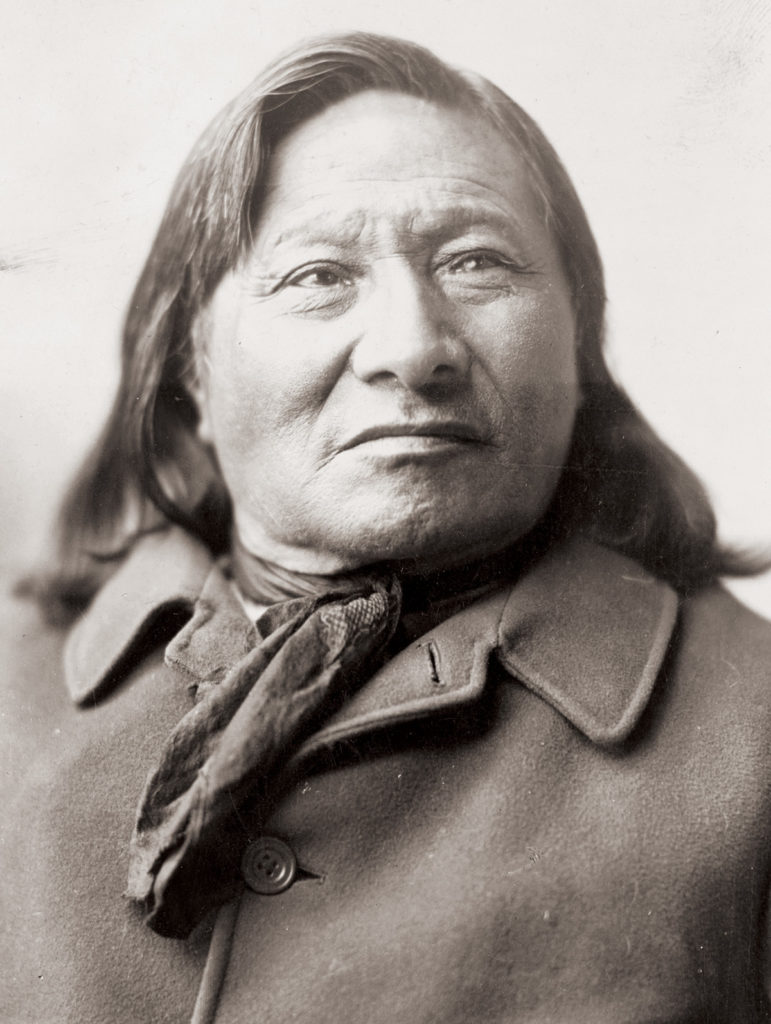

While most of the Sioux were adjusting to reservation life, several troublesome non-agency bands remained at large, including the Hunkpapa one under de facto leader Sitting Bull. Such bands were upset with the Northern Pacific Railroad, which was laying track ever closer to the last of their traditional buffalo hunting grounds. In August 1872 the government scheduled a follow-up peace conference at Fort Peck, a trading post in northeastern Montana Territory. As in the past, Sitting Bull refused to attend. Instead, he sent his brother-in-law with instructions to inform the assembled officials Sitting Bull would only consider attending “whenever he found a white man who would tell the truth.” His absence didn’t stop the government from recruiting Sioux of lesser standing for a goodwill trip that fall to Washington, D.C. Assigned to the party as an interpreter, Johnnie handled not only the day-to-day communications between federal officials and their wards, but also the flood of reporters who swarmed the Indian contingent at every whistle-stop. Arriving in Washington on September 15, the group returned to the reservation via New York City in late October.

Bruguier resigned his agency position on May 31, 1873. By then the Army had sent Lt. Col. George Custer and the 7th U.S. Cavalry to Dakota Territory to protect Northern Pacific surveyors from attack. According to author and researcher John S. Gray, although Johnnie’s name doesn’t appear in official Army records as having accompanied Custer’s forces, he likely came along as an interpreter or scout or both.

During the 1873 Yellowstone Expedition two civilians—Dr. John Honsinger, a veterinarian, and Augustus Baliran, a sutler—were riding ahead of Custer’s main column, seeking water for their horses, when a party of Sioux warriors ambushed and killed them. Bruguier would soon learn the identity of the killer. That fall Edmond Palmer, O’Conner’s successor at the Grand River Agency—which had been moved up the Missouri and renamed Standing Rock—hired Johnnie. During that bleak and bitter Dakota winter some of the non-agency bands camped near the agency to take advantage of government rations. Lingering around the lodges of these new arrivals, Johnnie overheard Rain-in-the Face, the Hunkpapa war chief, bragging about having murdered Honsinger and Baliran.

On Feb. 10, 1874, Bruguier resigned his agency job and returned south along the Missouri to visit his family in Sioux City. En route he informed Colonel David S. Stanley, the commander at Fort Sully, about Rain-in-the-Face’s boastful confession. Stanley forwarded the information in a March 1 letter to department headquarters in St. Paul:

“John Bruyere [sic], an educated half-breed, came here from Standing Rock yesterday. He informs me that the Indian who murdered the veterinary surgeon, Honsinger, and Mr. Baliran last August on the Yellowstone is now at Standing Rock Agency and boasts daily of having killed both these men with his own hand. The Indian says that the rest of the party wanted to spare the lives of the two unfortunate men, but that he killed them himself. Besides Bruyere, several white men have heard the Indian make this boast. To corroborate all this, Bruyere brought down Honsinger’s saddle and equipment, which he bought from the Indian. There is no difficulty of proving the murder, if the Indian can be caught. The arrest of the Indian will be a matter requiring address and force, as it may lead to a collision with all the Uncpapas [sic] camped at Standing Rock. I respectfully advise that the arrest be entrusted to Lt. Col. G.A. Custer, with not less than 300 men.

“John Bruyere will be at home, 2 miles from Sioux City, about the time this letter reaches St. Paul and is perfectly willing to go as guide. He was out as scout last summer and is well known to General Custer. If the department commander thinks favorably of this arrest, I would suggest that he summon John Bruyere to come to St. Paul to learn the full probabilities of success. A dispatch, care of Captain [W.W.] Foster or Mr. John H. Charles, would reach Bruyere at once.

“Notwithstanding all the murders the Sioux have committed on this river, there has never yet been an arrest, and this seems to me to be a favorable opportunity. Standing Rock is only 25 miles from Fort Rice, and the march can be made in one night.”

Stanley’s superiors met his letter with decided inaction. But later that year Rain-in-the-Face, unrepentantly boastful as ever, reappeared at Standing Rock. Apparently, that bit of news made its way north to the desk of Colonel Custer at Fort Abraham Lincoln. Still furious over the two civilian murders during the Yellowstone Expedition, Custer dispatched Captain George W. Yates and two companies of cavalry to arrest Rain-in-the Face. Yates did so on December 14, and in his report the captain gave high praise to Bruguier for his reliability and good service to the troopers by helping them identify Rain-in-the-Face.

Cloud of Suspicion

Till then Bruguier’s life and career had run along fairly conventional lines. He might have gone down as an obscure footnote in the chronicles of the Old West. But an incident at the agency on Dec. 14, 1874—exactly a year to the day after Rain-in-the-Face’s arrest—recast Johnnie in the minds of many from trusted scout to wanted murderer. The Bismarck Tribune broke the news:

“STANDING ROCK, D.T., Dec. 16: A sad affair occurred here Tuesday evening [December 14] about 10 o’clock that has resulted in the death of William McGee, an employee at the agency, from a blow delivered by Billy Brughier [sic], a half-breed Indian. It seems McGee was about retiring when Brughier and his brother John, the agency interpreter, entered the room considerably under the influence of liquor. McGee evidently endeavored to get one or both of the boys to bed when Billy fired two shots at him from his revolver, missing his aim entirely; he then struck him a terrible blow with his revolver just above the left ear, fracturing the skull in four different places. Word was immediately sent to the guard at the garrison for assistance in searching for the murderer, who had immediately proceeded to the stable and, mounting his pony, had fled to Two Bear’s camp, about 2 miles above the agency. Lieutenant G.B. Walker, of the 6th Infantry, proceeded to the Indian camp yesterday with a small party in search of Brughier, but it was found that he had fled. He is supposed to have gone to Bismarck and from there to Minnesota in order to get among the Red River half-breeds, he having expressed such as his intention.

“McGee was a quiet, hardworking man and leaves a father, mother and daughter living at last accounts near Martinsburg, [W.]Va.

“Assistant Surgeon T.A. Davis and Dr. S.S. Turner held a postmortem examination of the remains this morning.

“This same Brughier, but a few days ago, attempted to shoot John McCarthy, of Bismarck, and when under the influence of liquor is always trying to kill someone.”

Within days an Army patrol tracked down Billy and turned him over to federal officials in Bismarck. Sentenced to a 10-year prison term in June 1875, he was pardoned by the Dakota territorial governor on New Year’s Day 1882, having served just seven years of his sentence.

Although Johnnie hadn’t struck the deadly blow, he, too, had fled and was eventually charged as an accomplice in the murder. In the minds of many of his contemporaries, as well as subsequent historians investigating the matter, his flight only established his guilt.

The Bruguiers had both relatives and fast friends among the Sioux, and Johnnie drew on those contacts to hide him. On hearing a warrant had been sworn out against him, he headed southwest into the Black Hills. In February 1876 the warrant reached the U.S. marshal in Yankton, who dispatched a posse into the hills to seek out the half-blood fugitive. But Johnnie eluded them, and the posse returned to Yankton in July without its man.

According to a 1932 letter written by nephew John Bruguier, his uncle soon sought refuge in the lodge of Sitting Bull himself. In late August 1876, mere weeks after the shocking defeat of Custer’s 7th Cavalry command on Montana’s Little Bighorn River, Johnnie arrived in the Hunkpapa camp wearing the garb of an Army scout. Warriors were ready to brain him on the spot until Sitting Bull intervened. “Well, if you are going to kill this man, kill him,” the iconic leader reportedly told his warriors, “and if you are not, give him a drink of water, something to eat and a pipe of peace to smoke.” Thus accepted into Sitting Bull’s band, Bruguier served as an interpreter in many tense encounters between the Army and the fugitive Hunkpapa leader, who stalwartly refused to surrender, let alone move to the reservation.

By year’s end a weary Bruguier resolved to get back into the good graces of his former employer. Breaking off from Sitting Bull, he joined Iron Dog’s Hunkpapa band, which that October 31 made a winter truce with agent Thomas J. Mitchell at Fort Peck. Johnnie approached Mitchell with a Little Bighorn relic one of Sitting Bull’s warriors must have looted from the battlefield—a paymaster’s check for $127 made out to Captain Yates and endorsed over to Captain William W. Cooke. Both Yates and Cooke had died with Custer on June 25. The peace offering worked, as Mitchell welcomed Bruguier back into the fold.

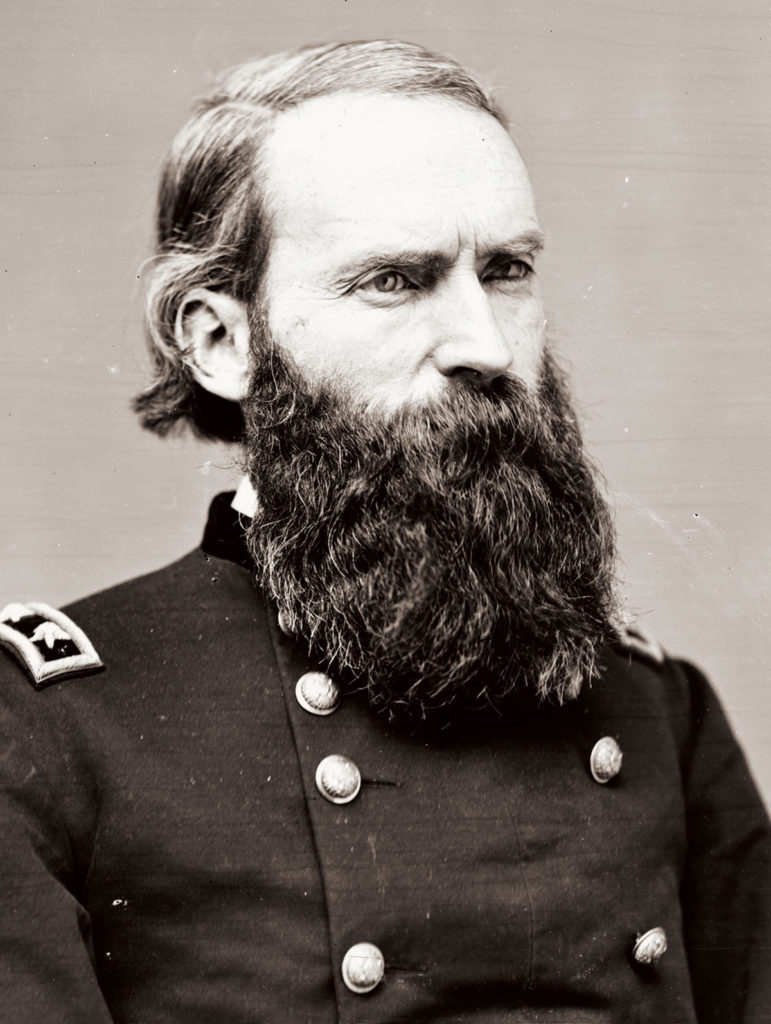

Meanwhile, the Army kept hot on the trail of Sitting Bull. Colonel Nelson Miles, tasked with bringing in the elusive chief, tapped Bruguier for advice. On November 17 the two made a deal: Johnnie would employ his significant skills to track down and bring Sitting Bull to the negotiating table, and Miles would do what he could to assist Bruguier with his legal trouble. When Miles set out with his troops after Sitting Bull, he made use of Johnnie’s intelligence. The colonel must have been pleased, as on December 17, a month after striking their deal, Miles hired Bruguier as a regular Army scout.

Johnnie proved invaluable in subsequent Army campaigns against Crazy Horse, Lame Deer and Chief Joseph. He frequently rode alone into hostile Indian camps, bearing messages to and from field commanders and Indian chiefs. His superiors praised his courage and mentioned him in dispatches as a reliable and trusted scout.

Regardless, Bruguier remained under a cloud of suspicion in the murder of William McGee, and on Sept. 27, 1879, authorities finally arrested the fugitive scout at Fort Keogh, in southeastern Montana Territory. Though Johnnie faced federal prosecution, he took heart from the fact that nearly every citizen of neighboring Miles City signed a petition of clemency on his behalf. Town namesake Colonel Miles also let it be loudly known Bruguier was the best scout he had ever employed, and that he was convinced of Johnnie’s innocence. The case went to trial in Fargo on December 30 and 31. Despite the determined efforts of the district attorney to blacken the scout’s character, the jury deliberated but a half hour before returning a verdict of not guilty.

Bruguier continued to serve off and on as a scout for his old friend Miles, who was promoted to brigadier general in 1880 and major general in 1890. That year Johnnie retired from Army service and settled near Poplar, Mont., on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation. There, on June 13, 1898, the old scout’s lifeless body was discovered on a lonely road. His head had been caved in with a wagon wrench. Authorities soon arrested another half blood, Ernest Strikler, for the crime. The motive went unrecorded, but it’s ironic that a man who had been in the thick of things on either side of the Indian wars was ultimately brought down by a wrench rather than a bullet or a tomahawk.

Aaron Robert Woodard, who writes out of Hartford, S.D., teaches history and government at Purdue University Global and American history at Bellevue University. For further reading he recommends The History of Dakota Territory, by George W. Kingsbury; History of South Dakota, by Doane Robinson; and “What Made Johnnie Bruguier Run?” by John S. Gray, published in the spring 1964 (Vol. 14, No. 2) issue of Montana: The Magazine of Western History and available online.