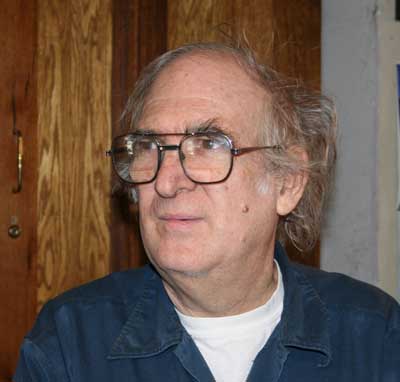

In the Hands of a Craftsman:

Master gunsmith John Zimmerman, an expert on Civil War firearms, is right at home in Harpers Ferry, W.Va.

How did you become a master gunsmith?

I grew up in Ohio and then was in Army ordnance for three years. When I got out, I went to gunsmithing school in Colorado. My family have been gunsmiths ever since they came to this country in the 1640s. They made guns for the Revolutionary War. One segment of the family worked in the armory here in Harpers Ferry from 1800 to 1842. In the Industrial Revolution, they were told they would no longer be gunsmiths and would have to tend machines. They didn’t like that; they were skilled artisans. That side of the family was named Hawken. They developed the Hawken rifle, which is a take-off on the Model 1803 Harpers Ferry rifle.

How long does it take to repair or restore a gun?

That depends on a hundred million different things. It can take anywhere from a week or two, to two or three years. The biggest thing is trying to find original parts. That can be like looking for a needle in a haystack a lot of times. Some people don’t want to have parts made; they’re insistent that everything be original. I try to find parts by going to gun shows, getting on the Internet, things of that sort. Trying to locate them can be a very difficult operation.

What about modern reproduction guns?

Most of them come from Italy or India, and they have foreign writing on them. We do what’s called “defarbing.” We take off the writing, move the serial number from the side to the bottom of the barrel and then restamp it with the appropriate markings of the period. The originals back then never had serial numbers. You cannot remove a serial number, but you can move it. As long as it’s on the gun somewhere and is legible, that keeps everybody happy. We take our time and rework the gun so it looks more like an original for the customer.

Are there limits on what you can restore?

I don’t restore guns manufactured after 1898, which is the cutoff date set in the 1968 Gun Control Act. I have to keep track of everything, and it’s a mountain of paperwork. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms could come in here anytime; if there’s so much as even an “i” that’s not dotted, that’s a $500 fine. There are some gray areas. For example, the 1873 Winchester is a problem because the cartridges for it are still made, whereas they aren’t for the ’76 Winchester.

What’s your connection to the Civil War?

Most of my customers are Civil War re-enactors, skirmish shooters, living historians and gun collectors. My great-grandfather, who ran the family gun shop in Ohio, was born in 1855, so he was too young to serve in the war. But he had two brothers and a brother-in-law that were killed. Another brother was in the ordnance department with Sherman’s army. We like to call him a pyromaniac in General Sherman’s arson squad. He said he burned off half the state of Georgia and the only thing he was ashamed of was not burning off the other half. After losing two brothers, he felt terrible revenge.