The House that Booth Built:

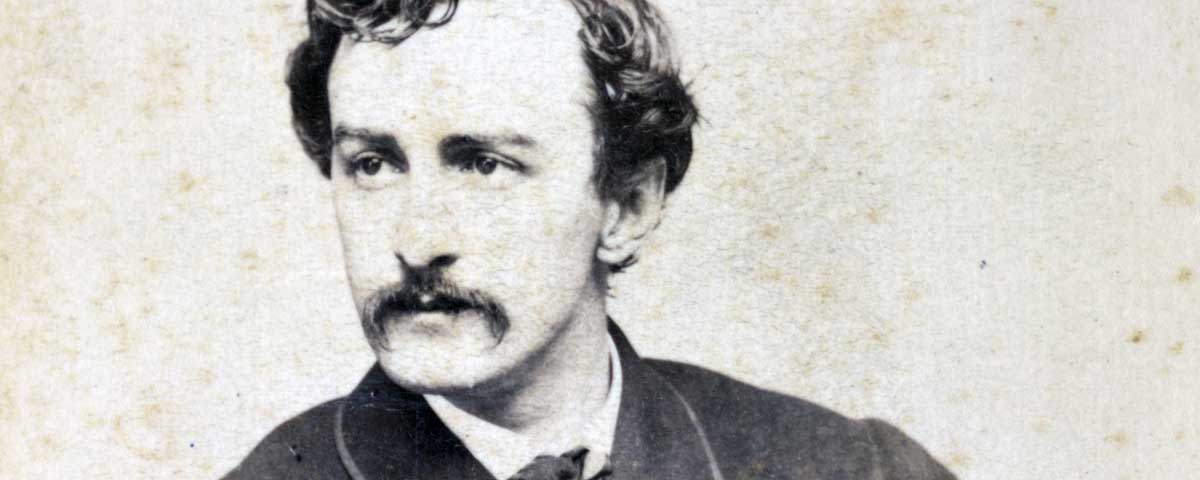

Maryland’s Tudor Hall, home of the theatrical Booth family, helped to shape a future assassin

After the tragic events of April 1865, the New York Tribune printed a rumor that the local residents around Bel Air, Md., could easily believe: Abraham Lincoln was probably not the first man John Wilkes Booth ever killed.

During the war, a small band of Unionists had camped not far from the Booth family home in Bel Air—a small town in Harford County, east of Baltimore—which the family had named Tudor Hall. As a border state, Maryland was torn between Union and Confederate partisans, often within a single family, and the Booths were no exception. This was a family of renowned actors, a household where giving free vent to the emotions was encouraged. On at least two occasions, the Tribune reported, the impetuous John, a longtime Southern sympathizer, had rushed into Tudor Hall, grabbed his rifle, and run off to join the local Confederates skirmishing against the bluecoats in the nearby woods.

Whether or not John actually killed anyone there is an open question. But history has recorded that, after Lincoln was assassinated, the neighbors had nothing good to say about him. “[N]one of the neighbors ever liked the family, who were the devil’s own play-acting people, and would do anything bad,” the Tribune quoted one man saying. Rumor had it that the young Booth of Bel Air liked to get his kicks by shooting local dogs or farm animals. Once a killer, always a killer, according to the locals.

And yet the story of Tudor Hall paints a more complicated picture of John Wilkes Booth and his tempestuous family. It was, in some ways, a happy home, given to flights of fancy, grand gestures and elaborate “play-acting.” It was a place where John pretended to be Romeo (or perhaps Juliet) from the balcony off his bedroom, where he is assumed to have carved the initials J.W.B. found on a nearby beech tree, and where he “was known to be loved,” according to subsequent owner Ella Mahoney, who wrote memoirs of Tudor Hall and the Booth family.

But Tudor Hall was also a house of dark corners, where the mercurial John had deliberately chosen an eastern-facing bedroom because he didn’t like to watch the sun set. There, the family mourned the loss of its gifted patriarch, Junius B. Booth Sr., who had chosen the house’s design and overseen its construction but died before he could live there.

As a master tragedian, the elder Booth knew something about messy affairs of the heart. In his professional life, Junius had played such tortured leading men as Hamlet, Caesar and Richard III, but his personal life was nearly as dramatic. In 1821 the London-born Booth had abandoned his wife Adelaide and young son in England (a daughter had died in infancy) to accompany his lover, Mary Anne Holmes, to America, where they set up housekeeping in downtown Baltimore. The couple would eventually have eight children together, four of whom would die in childhood. Their life was comfortable, supported by Booth’s soaring acting career, which sent him to the tread the boards in Boston, New York and other major cities. He soon longed for a bit of privacy and fresh air, and purchased a log cabin in Bel Air in 1823 to serve as a summer retreat for the family. It was there, on May 10, 1838, that John Wilkes Booth was born.

By all accounts, Junius threw himself into farming, planting a vineyard and orchard, harvesting crops and corralling horses and cows. He sent away for farming journals and studied them closely. Despite his fervor, Junius took a humane approach to his animals. He insisted that no livestock be slaughtered on his property, purchasing meat at neighboring farms. Several of his children, including John, were raised as vegetarians. Junius, who was accustomed to velvet and brocade in his costumes, farmed his land barefoot and was known to neighbors simply as Farmer Booth.

In the mid-1840s, when Junius sought to upgrade their homestead, he turned to an architectural pattern book published by William H. Ranlett in 1847. Ranlett was a well-known architect whose most famous work is the Hermitage, now a national historic landmark in New Jersey. Booth chose Ranlett’s design for a 1½-story Gothic Revival cottage with a front-facing gable and Palladian symmetry. The brick house was painted green to reflect its bucolic surroundings, and the interior living rooms and parlors were cozy, with a fireplace in the middle of the main room. A free-standing kitchen was only feet away. For the construction, Booth chose James J. Gifford, a respected carpenter in the region. (Ironically, Gifford would later be employed by John T. Ford to build his theater in Washington, D.C.)

It is perhaps not surprising that a renowned actor could pull off leading a double life. For years, Junius sent money home to support his family in England, and it is thought that Adelaide was none the wiser about his home life in America (though one never knows). But by the late 1840s, the truth was out. Adelaide and Junius were divorced in 1851. That same year, some 30 years after their affair began, Junius and Mary Ann were married. Their official union, like those in the Shakespearian tragedies he knew so well, was short-lived. The following year, Junius contracted consumption of the bowels after a six-night stand in New Orleans and expired on a riverboat en route to Ohio. His last words, according to his daughter Asia, were “pray, pray, pray.”

After his passing, one admirer wrote a tribute to Junius in a literary journal, saying, “There are no more actors.” For the grieving actor sons, including John and older brother Edwin, also a leading light of the American stage, the death of their father was no doubt the hardest act to follow.

Now without its head, the family moved into their new home, Tudor Hall. Edwin stayed only briefly, but John resided there with his mother, sisters Asia and Rosalie, and younger brother Joseph. According to Asia, there was little for the young Booths to do, perhaps a blessing and curse for youngsters with active imaginations. Occasionally Asia and John attended a church event or dance, but mostly they read aloud to each other or recited lines from plays or whiled away the hours climbing the great cherry tree near the house. Once, when some of Asia’s friends visited, John whipped up a simple supper of pancakes. He sometimes fell into melancholy, reminding family and friends that a fortune-teller had predicted he would meet a bad end and die young. As the nation moved toward war, his support of the South became more trenchant, leading to arguments with his Unionist brother Edwin. (Years later, when Edwin received a trunk of John’s, filled with costumes and love letters, he burned them.)

By the outbreak of the Civil War, the Booths had rented Tudor Hall to the King family from Washington, D.C. Although they kept some belongings at Tudor Hall, they rarely returned, except for John, who had “a strong affection for his boyhood home and friends,” according to Ella Mahoney. He mostly toured the country as an actor whose reputation was growing (his early outings, when he was still a teenager, earned scathing reviews, but he had grown accomplished in his craft). He was well-known to Ford’s Theatre audiences, and once pointed directly to President Lincoln in his box during a scene. In his last appearance there in March 1865, he played Duke Pescara in The Apostate—the lead role, and a villain.

A month later, John turned his villain act into reality. By April 15, 1865, Lincoln was dead, John Wilkes Booth was on the run in southern Maryland, and soldiers surrounded Tudor Hall. Mrs. King stepped out onto the balcony—perhaps the same one young John had once play-acted on—where the troops called up to her, demanding to be let in. For 10 days they came and went, searching the house and grounds in vain. They didn’t know that the assassin was never to return to his beloved home.

The last act of the most dramatic role of his career was playing out, ensuring that his fame would forever eclipse that of his older brother or father. On April 26, 1865, after he was shot at the Garrett Farm in Virginia, John Wilkes Booth died near dawn, the time of day he had loved best.

Kim O’Connell, based in Arlington, Va., has a master’s degree in historic preservation. She wishes to thank Tom Fink, president of the Junius B. Booth Society, for his research and assistance with this story. This article was originally published in the June 2015 issue of Civil War Times.