American painting style grew out of heroic scenes, martyrs’ deaths, and massive historic murals

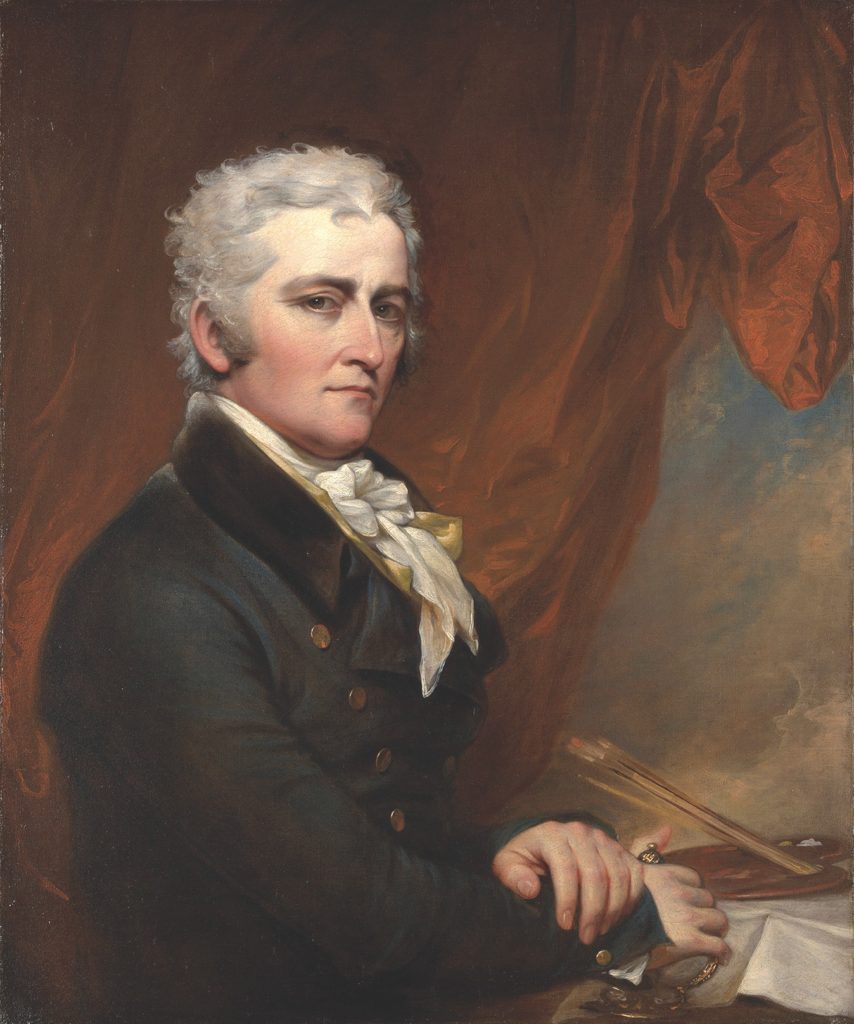

In 1780, John Trumbull arrived in London. He had left Connecticut for a business venture in France that failed. Now, fresh from that Parisian debacle, he meant to do what he had wanted since childhood: become an artist. A veteran of the rebellion still raging between the Empire and its American colonies, Trumbull had the political connections, the money, and the brass to set about buttonholing another American, Benjamin West, court painter to King George III, to take him on as a student. At West’s studio, Trumbull explained that he had obtained permission from Britain’s secretary of state for America, Lord George Germain, to study in London as long as he stayed out of politics. Wanting to test his visitor’s skills, West asked Trumbull to pick a painting from among those at hand and reproduce it as a drawing. Trumbull chose another artist’s copy of Raphael’s Madonna della Seggiola and set to work freehand. His dreams hung in the balance.

John Trumbull, youngest of six children, was born on June 6, 1756, in Lebanon, Connecticut. Father Jonathan, a prominent merchant, was Connecticut’s colonial governor. Mother Faith traced her New World roots to Mayflower passengers John and Priscilla Alden. The Trumbulls were a powerful Connecticut mercantile and political family whose children enjoyed fine educations in religion, business, politics, and classical studies. Older sister Faith had taken up oil painting. Her mother and namesake hung the daughter’s works in the parlor. John, seeing those canvases, attempted to reproduce them in pencil on the “nicely sanded floors” soon to be “constantly scrawled” upon with his childish drawings. The boy was around 10 when business reversals upended the family’s comfortable life. John became a loner, immersed in drawing. In 1771, besotted by John Singleton Copley’s English-style portraits of members of the American elite, he begged his father to let him study under Copley. Trumbull senior refused, sending his youngest to Harvard accompanied by older brother Jonathan, a 1759 Harvard alumnus. A mutual friend of Jonathan’s and Copley’s brought the brothers to the painter’s Beacon Hill house. Meeting his idol and seeing his work reinforced the youth’s desire to paint.

In addition to his coursework at Harvard, which owned and displayed many Copleys, John Trumbull, seeking to develop his technique, copied those canvases. He studied mathematician Brooke Taylor’s and artist Joshua Kirby’s theories on perspective and artist William Hogarth’s 1753 book Analysis of Beauty. Strongly interested in historical themes, at 18 he attempted his first original work, Death of Paulus Emilius at the Battle of Cannae, a composition he peopled with figures borrowed from engravings.

War interrupted Trumbull’s education. His oldest brother Joseph, thanks to their father’s sway, was a colonel in the Continental Army, in charge of commissaries. John joined up too, expecting Congress to issue him a formal commission reflecting his June 1776 enlistment. At Joseph’s urging, John, concealing himself in undergrowth at a point overlooking Boston, sketched British troop formations and bastions. Joseph saw that the sketches reached General George Washington. The general already had in hand British plans for those positions, but Trumbull’s enterprise and artistry earned him reassignment as an aide to Washington.

Although stationed in Roxbury during the Battle of Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill, Trumbull was near enough to hear the cannonades and see the burning buildings; later he heard details of the fight from veterans. When Congress issued him a commission, it was dated months later than his actual enlistment, infuriating him. In February 1777 he resigned from the army.

Returning to the family home in Lebanon, Trumbull had family and friends sit for him and also painted scenes from the Bible, antiquity, and mythology. His work was amateurish. In 1777’s Jonathan Trumbull Jr. with Mrs. Trumbull and Faith Trumbull, his subjects’ heads are woefully out of proportion, his rendering of fabric appears stiff, and his use of space is flat. However, the composition itself is strong and evocative. He moved to Boston, renting a room in a house once occupied by John Smibert, the first American artist to train in Britain. Smibert, a noted portraitist of the 1730s who designed the city’s first public market, Faneuil Hall, had died in 1751. Some of his work still hung in the house, and Trumbull soaked up those paintings’ details.

Entering the commodities trade in 1779, Trumbull headed to Paris. That venture failed, propelling him a year later to London and his pursuit of West as a teacher, largely for the other man’s expertise in historical painting. However, as King George III’s official painter West had to stay away from certain subject areas, like the American rebellion.

At their first meeting, Trumbull amazed West. Traditionally, artists used squares to achieve perspective, but West’s visitor, working freehand, was reproducing the Raphael copy with accuracy and vivacity. West agreed to take Trumbull on as an apprentice. The arrangement progressed until autumn 1780, during which time Trumbull painted, from memory, his first portrait of George Washington. The general stands on a hill above the Hudson River, flanked by his personal slave Billy Lee on horseback, with West Point off at a distance. On October 2, as a partial coda to the Benedict Arnold affair, the Americans hanged Major John André (“Tracks of a Traitor,” October 2017). In retaliation, British authorities arrested Trumbull on charges of espionage.

West’s patronage served him well; he was allowed to spend his seven-month term in relative comfort at Tothillfields-Bridewell prison, where by the time he was released in June 1781 he had completed a copy of Antonio Correggio’s St. Jerome’s of Parma.

Returning home, Trumbull declined offers to go into business and continued to resist his father’s urgings that he become a lawyer, protesting that he wished to emulate the great artists of olden times. “Connecticut is not Athens,” Trumbull senior answered. The two never discussed the subject again.

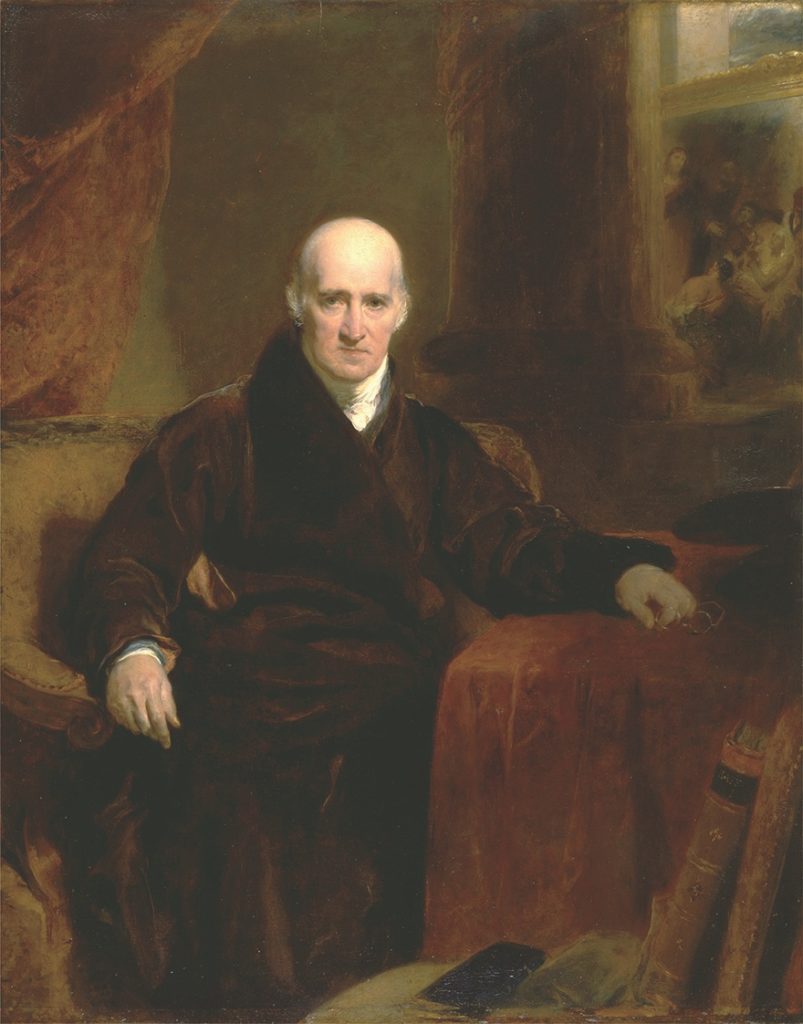

In 1783, with peace impending, Trumbull returned to London. His hero, Copley, had been living and working in London since 1774, exhibiting such paintings as Watson and the Shark, which had led him to be accepted for membership in the Royal Academy. Trumbull took evening classes at the academy and spent his days painting in West’s studio, where he, William Dunlap, and other students absorbed lessons from the master on technique and the “great style,” a neoclassicist school emphasizing clarity and harmonious proportions. Copley and West encouraged Trumbull to take on American historical subjects. Amid their urging and rampant examples in London galleries of heroic paintings on British themes, Trumbull found his calling and began working on what would become his oeuvre. West’s Death of General Wolfe influenced Trumbull’s The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, June 17, 1775, and The Death of General Montgomery in The Attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775. Copley’s much-praised The Death of Major Pierson also exerted influence on the younger man. Trumbull undertook Warren in 1785 and Montgomery in 1786. In commemorating those early revolutionary moments using the “great style” he portrayed Warren and Montgomery as martyrs expiring in their comrades’ arms.

Visiting London from Paris in 1785, American Minister to France Thomas Jefferson met Trumbull, admired his work, and invited the artist to call on him in Paris. Trumbull did, taking up residence in Jefferson’s home at the Grille de Chaillot. The men developed a close friendship and with Jefferson’s invaluable but fanciful feedback, Trumbull sketched The Declaration of Independence, a crowded scene that would have 48 human subjects in the initial version. By 1787, Trumbull had completed the composition in London, shelving the canvas to go to America and chase down the men whose faces he now had to incorporate into the work.

Arriving in New York in 1789, he visited President George Washington at his Manhattan residence. Washington agreed to sit for a portrait, dedicating one or two hours three times a week to the process and even exercising on horseback for his artist friend’s benefit. In 1790, commissioned by Martha Washington, Trumbull completed a full length portrait, George Washington at Verplanck’s Point, New York, 1782, Reviewing the French Troops After the Victory at Yorktown. The painting and Washington’s endorsement earned Trumbull his first large public commission, a 108”x72” painting to hang in New York’s City Hall. He completed Washington and the Departure of the British Garrison from New York City the same year.

From 1789 to 1793, Trumbull also traveled the East Coast painting 48 individual portraits—36 from life, the rest from existing works or by substituting deceased subjects’ sons. He painted some portraits onto the original canvas and made copies of the rest to be added later, completing Declaration in 1817. Trumbull gave Jefferson, primary drafter of the Declaration, pride of compositional place.

intended wife’s death and the resulting grief kept Trumbull out of the studio for almost seven years. He extended that break 1794-97, working abroad as a diplomat—first as secretary to John Jay in England until the signing of the Jay Treaty in November 1794 and then as a minor character in the fractious Franco-American episode now known as the XYZ Affair.

In 1800, he married Sarah Hope Harvey in London, moved his bride to America, and resumed painting. He showed Bunker’s Hill in New York and became a member and then vice president of the American Academy of the Fine Arts. His career proceeded until imposition of the Embargo Act of 1807 destroyed the American economy. Trumbull’s commissions dried up.

In 1808, in a flourish of bad timing, Trumbull returned to England, where tension over conflicts with the United States prevented him from landing assignments. He fell into debt, executing only a few religious paintings such as 1811’s The Woman Taken in Adultery and Our Savior and Little Children in 1812. West, now president of the Royal Academy, saw to it that Trumbull’s works were displayed there. With war impending in 1812, Trumbull tried to return home to the United States but was only allowed to relocate from London to the city of Bath, 115 miles west.

When Trumbull did get back to the United States in 1815, his countrymen were more receptive to his work. An 1817 showing of Declaration at the U.S. House of Representatives earned him a $32,000 commission from Congress to execute four 12’x18’ oils, one an enlargement of Declaration, to hang in the Capitol Rotunda. He completed the larger Declaration in 1818, followed by Surrender of Lord Cornwallis in 1819; Surrender of General Burgoyne, in 1821; and General George Washington Resigning His Commission to Congress, in 1824. To mark the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the four canvases were installed in the Rotunda on July 4, 1826.

Art is fashion, and fashion changes.

By the 1830s, art critic William Dunlap, a rival since their days as West’s students, was lambasting Trumbull’s historical paintings as inaccurate and lacking credibility—“among the greatest and unaccountable failures of the age,” he called them, impugning Trumbull for quitting the Army in the middle of the Revolution and spending much of that war and all of the War of 1812 living abroad.

Strapped, Trumbull sold his stock of existing paintings to Yale, creating the first American gallery associated with a university, in exchange for an annuity of $1,000 yearly for life. He wrote and published an autobiography defending his work; the book sold badly.

Trumbull was 87 when he died on November 10, 1843. He is appreciated today for his focus on American subjects, which helped establish a new genre, American art, and idealistically imagining the nation’s origins.

This story appeared in the February 2020 issue of American History.