Farmer’s son endured combat, enslavement, and near-execution before his talents as a diplomat brought peace with the Algonquians

The name “John Smith” has come to convey anonymity, but one holder of that moniker stands out. Early American colonist John Smith may have made his name in America, but by the time the 27-year-old arrived at Jamestown, in Virginia, he had experienced a lifetime’s worth of experiences. As a youth, he ran away to be a mercenary, survived single combat, was captured and enslaved, escaping his Turkish captors in a harrowing bolt across eastern Europe. Sailing to Virginia, he so provoked compatriots that they nearly hanged him, but again Smith prevailed and brought to bear his talents, saving Jamestown from disaster and establishing the first permanent English settlement in North America.

Born in Lincolnshire in 1580, Smith hankered from boyhood for what he called “brave adventures.” His father, a prosperous farmer, died when his red-haired oldest son was 13, leaving young John seven acres of land. Apprenticed by guardians to a wealthy merchant, the boy ran away at 16 to join a company of English mercenaries in France, selling his satchel and schoolbooks to pay for his passage. He first went to war in the service of King Henry IV of France, then hired on in Holland to fight for the Dutch against their Spanish overlords.

Smith returned briefly to Lincolnshire and his inherited acres, but by 1600 was back on the continent, spending two years siding with the Austrians against the Ottoman Turks. In sequential hand-to-hand fights, the Englishman bested three Turks, offering his foes’ heads to Sigismund Bathory, prince of Transylvania. Promising Smith a pension, the prince honored him with a shield of arms featuring three severed heads.

Smith was 22 when he ran out of luck. Wounded at the Battle of Rottenton, in present-day Romania, and captured by the Turks, he and fellow prisoners stood herded on display “like beasts in a market-place” while merchants bid on them, he wrote in a 1630 memoir, The True Travels, Adventures, and Observations of Captain John Smith. Marched nearly 300 miles to Constantinople in ranks of “twentie and twentie chained by the neckes,” the captives went where their new masters ordered. Smith spent a year on a Turkish noble’s remote Black Sea estate as the lowest “slave of slaves.” Although living miserably, he later was able to recollect myriad details with anthropological precision, including clothing, landscape, buildings, and diet, such as Turks’ most common meal—couscous boiled with bits of horse entrails and other meat—and favorite drink—“Coffa.”

Smith kept alert for opportunities to escape, and finally did. As he was threshing grain in an isolated field, his owner arrived to oversee and “beat, spurne, and revile” him. Smith lost his temper and with the threshing bat crushed the noble’s skull. After donning the dead man’s clothes and hiding the body under a mound of hay, he mounted the man’s horse, riding west for 16 days in “feare and torment,” expecting to be recaptured by Turkish troops.

A friendly Russian garrison took in the fugitive, letting him recover. Smith crossed Europe, detouring to Transylvania for the promised pension, and in 1604 reached England.

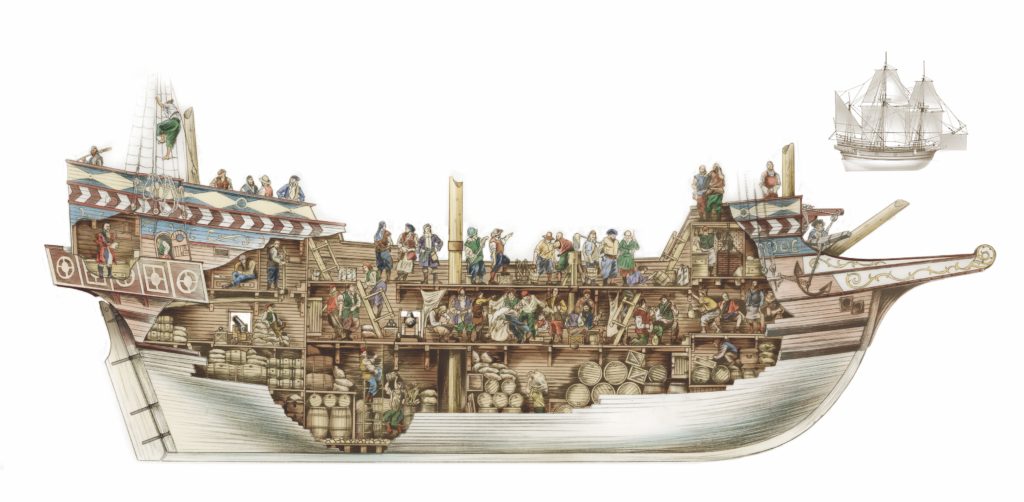

King James I, eager to gain a toehold in North America, had anointed private ventures aimed at commercializing the New World for England. James assigned the London Virginia Company to set up a proprietary colony on the American continent’s middle Atlantic coast. Smith signed on. In 1606 the company’s men sailed aboard Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery. The voyage took weeks longer than anticipated, forcing the passengers to consume supplies intended to sustain them ashore.

Most of the 105 would-be colonizers were nobles able to afford an adventure but short on experience—soft-handed fellows for whom manual labor was an anathema. The remainder of the roster consisted of the gentlemen adventurers’ servants, a few carpenters and similar artisans—and Smith, who stood out sharply in background and temperament.

Although Smith was a landowner, he ranked far below the gentry in social status, sometimes a source of friction between him and his companions. Smith so annoyed expedition leader Edward Maria Wingfield that Wingfield accused the former mercenary of mutiny, had Smith clapped in irons, and considered hanging him as soon as a tree was within reach.

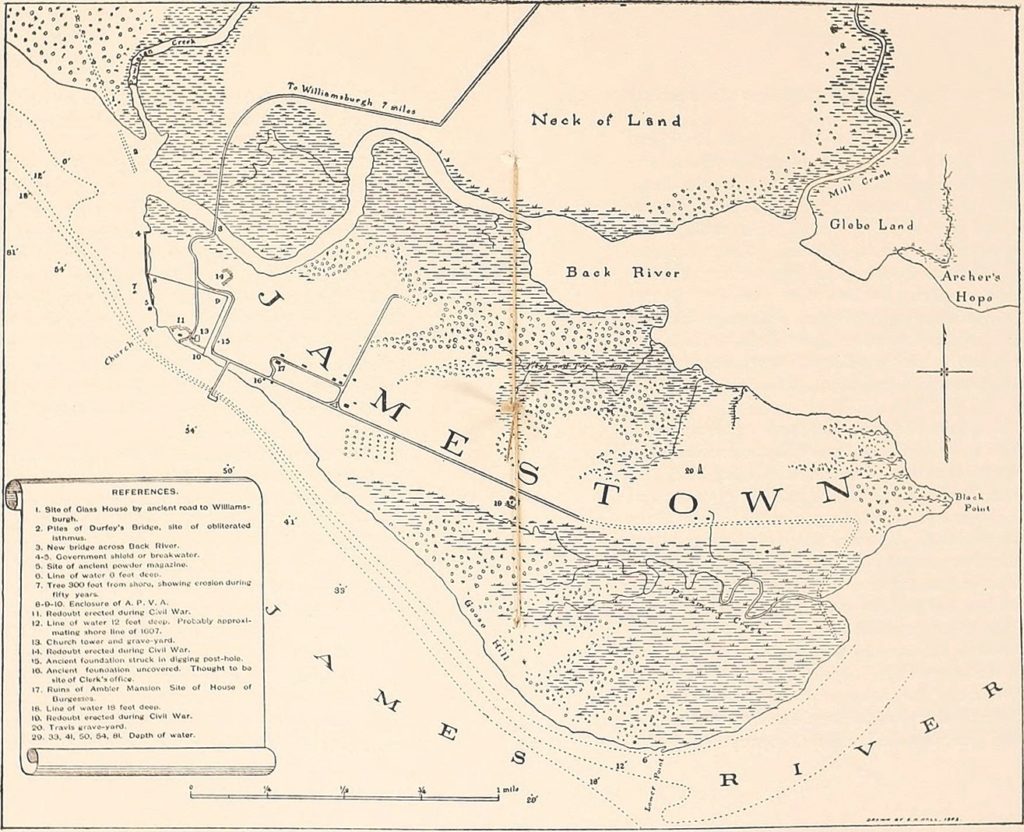

Sailing into an estuary called Chesapeake Bay on April 26, 1607, the new arrivals beheld an alien landscape, wild and overgrown, populated by unnamed beasts and forested to the very shore with immense trees. Weedy marshes marked the mouths of a dozen or so rivers emptying into the bay. Though generally mild of weather, the region in summer was punitively humid and, in Smith’s words, “hot as in Spaine.”

Anchoring at the marshy mouth of a river, the English sent a boat ashore, whereupon a volley of arrows seriously wounded two men. The next two weeks brought several Indian surprise attacks and two deaths. The expedition was down to its last barrels of barley and wheat, which casks, according to Smith, contained “as many wormes as graines.” The ships’ crews set sail for home with plans for a resupply run, but that would take months.

Opening their sealed orders, the colonists saw that their primary missions were to find valuable minerals, especially gold, and to use a small sailing barge, or shallop, to explore as far as possible up any rivers—especially streams that “bendeth toward the north-west” and perhaps led to the “northwest passage” said to link the Atlantic with the Pacific Ocean. The orders also listed Smith as a member of the colonial leadership council. Off came the irons.

The colonists called their impromptu settlement Jamestown and the river the James, both after their royal patron. The enterprise got off to a bad start. Fresh water was in short supply. Mosquitoes and humidity were not.

The artisans built a protective palisade, but not huts to replace tents that rotted quickly in the humidity. Only when Smith chivvied them did the men plant crops.

Doggedly obeying orders, colonists wasted months digging glittery, useless iron pyrite, also known as fool’s gold. They slogged only 60 miles or so up rivers before running into impassable white water. The Englishmen never achieved amity or did much business with local Indians.

Around two dozen Algonquian tribes—at least 15,000 people—lived in the area, subsisting on what they hunted, fished, and gathered, as well as growing and harvesting beans, corn, pumpkins, tobacco, and other crops. Small villages, usually on waterways, dotted the region. Each tribe had its own leader, but most paid tribute to the paramount regional chief, Wahunsonacock, leader of the Powhatan tribe. The English, who called him Powhatan, struggled with the Algonquians from the start. Commercially minded tribes offered to arrange a truce between the English and less friendly groups, but sporadic violence persisted. As of September 1607, 50 Englishmen had died, mostly from disease arising from unhealthy living conditions. Survivors were running out of food.

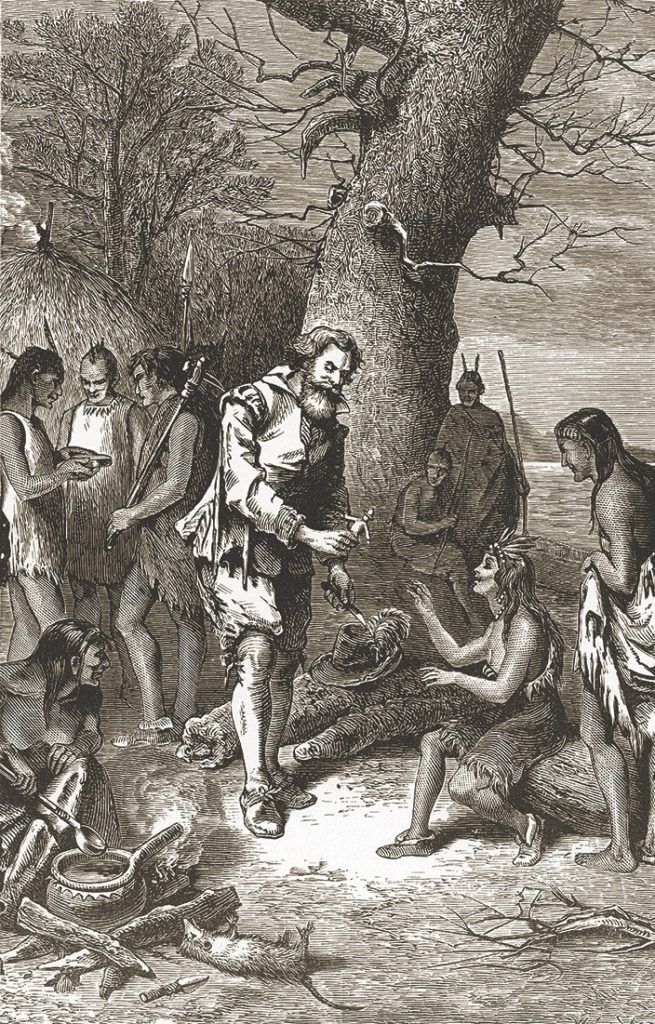

Smith’s survival instincts and experience with other cultures now came to good use. Roaming the vicinity of Jamestown in search of tribes willing to trade corn and meat for copper, hatchets, knives, and other artifacts, he struck deals with the Chickahominy and other tribes. Traveling by river, the red-bearded Smith would find people waiting on the banks with baskets of corn. He bartered for “Venison, Turkies, wild foule, bread,” and other provisions, and learned Algonquian. In December 1607, he and nine companions sailed, poled and rowed the expedition’s shallop as far up the Chickahominy River as they could. Smith and two other men continued by canoe to a locale farther upstream. Smith was away hunting when members of the band led by Opechancanough, Powhatan’s brother, killed the other two Englishmen. Seizing Smith, the Powhatan marched the Englishman to a village where they confined him to a longhouse. After two days, Smith’s captors took him to another village, Pamunkey, home of Opechancanough, for several days of ceremonial dancing and eating, staged in part, a dancer told Smith, to divine the Englishman’s aims—“if he intended them well or no.”

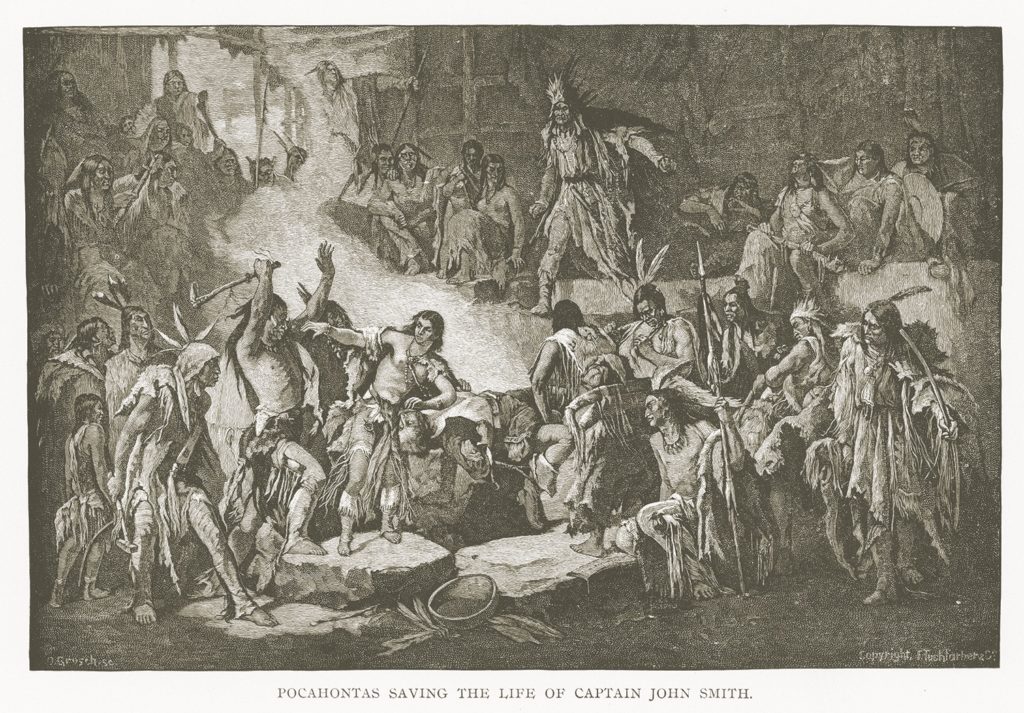

At the beginning of January 1608, Smith’s captors took him to Werowocomoco, the village where Chief Powhatan held court. Using a native word for an animal previously unknown to him, Smith later described the scene in his history of Virginia: Powhatan sat before a fire “upon a seat like a bedsted … covered with a great robe, made of Rarowcun [raccoon] skinnes, and all the tayles hanging by.” More than 200 courtiers, including family members, milled about. A woman brought Smith water with which to wash his hands. Someone else brought food, whereupon “a long consultation was held.” At the end of this discussion, several men laid “two great stones” before Powhatan, dragged Smith onto the rocks, and raised their clubs “to beat out his braines.” At the last moment, the king’s daughter Pocahontas, 13, flung herself down beside Smith, cradled his head, and “laid her owne upon his, to save him from death.” Powhatan waved off the would-be executioners.

The Indian king and the Englishman began negotiating. A deal coalesced.

“Hee promised to give me Corne, Venison, or what I wanted to feede us,” Smith wrote in 1609. “Hatchets and Copper wee should make him, and none should disturbe us.” A detachment of Powhatan’s men escorted Smith to Jamestown.

Though he made much of the dramatic scene in later writings, Smith didn’t mention this episode in early reports to England.

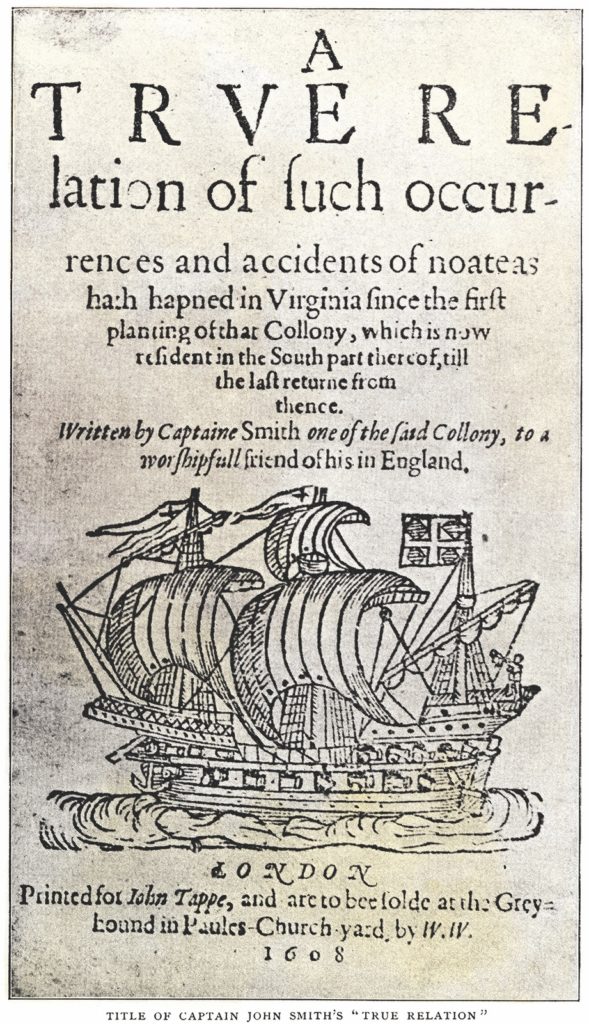

In a 1608 letter to British overseers published as A True Relation of Virginia, Smith describes Powhatan’s court down to the great robe “made of Rarowcun,” and details the agreements, but doesn’t mention Pocahontas. Not until the 1624 Generall Historie, a much longer book, does he tell the complete story. These discrepancies have led skeptics to suggest Smith was a fabulist, but other records of the time indicate that the story is true. Lately historians have said that the sequence of events might have been an elaborate ritual designed to “adopt” Smith into the Powhatan tribe, with no threat to his life—a reading Smith likely would not have made. Considering events of his earlier life, the scene at the court simply might not have seemed to him to be worth including in a brief official report.

Things started looking up for Jamestown. The larder was stocked, and a period of relative peace and stability unrolled. The colonists and the Powhatan met often, with Smith the designated interpreter and chief English negotiator. He put an end to gold fever, whose victims had eschewed other labor to chase the yellow metal, by announcing, “He that will not work shall not eat.” With more men building and planting, Jamestown started to take shape.

Over the next two years, Smith made a lasting impact, putting the colony on a stable footing, and gathering useful information for his investors and the government, until an accidental explosion injured him. He returned to England in October 1609. His boosterish 1614 Map of Virginia paints the region’s rivers, soil, weather, and other natural features as attractive. “No place is more convenient for pleasure, profit, and man’s sustenance,” he writes, mentioning a plum-like fruit, Putchamin (persimmon) that when ripe is “as delicious as an Apricocke.” The “Opassom,” he declares, “hath an head like a Swine and a taile like a Rat.” He explored the headwaters of the James River—site of present-day Richmond—and several tributaries, and characterized their length and navigability, as well as the people who lived along their banks.

Smith’s volume explicated Powhatan life, including how the tribe cultivated crops, what members wore, how they governed themselves, and how they buried their dead. Nearly all we know about the now-extinct Virginia Algonquian language comes from Smith’s records; whenever writing about a non-English phenomenon known in his part of the New World, he used the Algonquian word. He opens A Map of Virginia with a glossary of words and phrases that includes tomahawk and moccasin. Other Smith-sustained Algonquianisms include hickory and caucus, which originally referred to a tribal elder.

In 1614, after Smith had recuperated from the injuries that had sent him back to England, he again crossed the ocean to North America, this time to what is now Massachusetts. He was the first to map the coast around Cape Cod and to investigate the plants and animals of what he called New England. Algonquian terms he noted there include muskrat, terrapin, hominy, and moose (“a beast bigger than a Stagge”). In 1620, the Pilgrims sailed with a copy of Smith’s work, which may have influenced their choice of Plymouth as a place to settle.

Smith’s value to Jamestown came to light after he left. Without his leadership, the colony fell into disarray. The year that followed Smith’s departure became known as “the starving time.” Men retreated into their lazy ways, gobbling supplies, not planting. Relations with the Powhatan soured almost immediately. The Indians “no sooner understood Smith was gone but they all revolted,” a colonist wrote. Trading stopped. Violence proliferated. Supply ships, blown off course, were stranded for months in the Bahamas. Jamestown hung on. By 1611, rebuilding was under way. Within a decade, the leaders realized that a popular type of tobacco grew well in Virginia, assuring the colony’s future.

Smith tried to return to Jamestown in 1615, but French pirates attacked his ship and took him prisoner. After he spent months in captivity, the pirate ship came near enough to the French coast that Smith could chance escape by small boat. He succeeded, and stayed in England for good, composing his memoirs. John Smith died in 1631.

This story appeared in the April 2020 issue of American History.