A sculpture titled The Council of War occupies a prominent place in my library. Created in 1868 by the artist John Rogers, it depicts a seated Abraham Lincoln holding a large map and flanked by Lt. Gen. U.S. Grant and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Grant points toward the map with his right index finger while Stanton, cleaning his glasses, looks on. The idea for the grouping came from Stanton, who described a meeting in March 1864 when Grant, “after returning from his first visit to the Army of the Potomac, laid before the President the plan of operations he proposed to adopt.” Robert Todd Lincoln pronounced Rogers’ effort the most lifelike sculpted image of his father, and Stanton expressed similar admiration. Whenever I look at The Council of War, I imagine eavesdropping on three leaders who helped steer the United States toward victory during the war’s final tumultuous year.

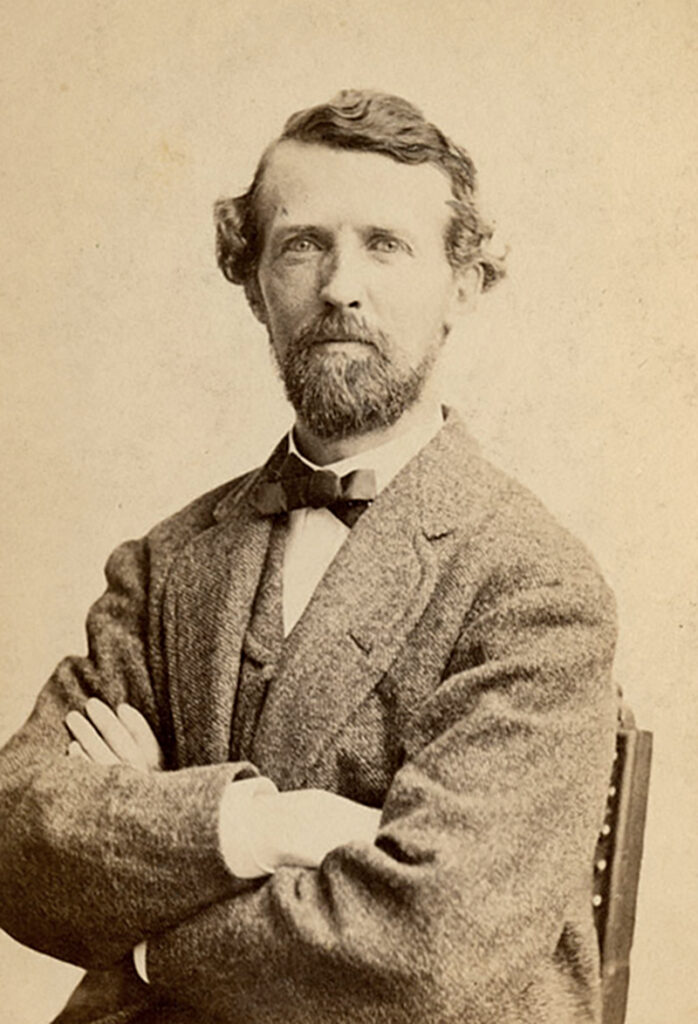

The Massachusetts-born Rogers (1829-1904) created scores of small-scale plaster sculptures for sale at modest cost to a middle-class audience. Between 1859 and the early 1890s, he sold an estimated 80,000 pieces. More than a dozen Civil War–related works reflected the artist’s staunchly pro-Union and pro-emancipation views. Although The Council of War features famous individuals, most of the works focus on common soldiers, civilians, and African Americans—usually in settings that resonated with the loyal citizenry at a fundamental level. A Boston newspaper characterized the wartime pieces as “packed with far reaching and penetrating suggestions of wide spread trials and joys.”

Two works from 1863 deal with correspondence between soldiers and their families and friends at home. Rogers explained the scene in Country Post Office: News From the Army: “An old shoemaker, who is postmaster also, has just opened the mailbag from the army. He is taking a provokingly long time to study out the address of a letter which a young lady by his side recognizes at once as for her.” One reviewer suggested the woman, eager to get her letter, could have been a wife, sister, or lover—which meant a wide range of viewers might see in Country Post Office their own personal experience. Mail Day reversed the perspective, offering a soldier with a writing table in his lap and a pensive look on his face. “It is the day for the mail to close,” wrote Rogers, “and a soldier is puzzling his brains so as to complete his letter in time.”

Rogers addressed disparate themes in a pair of works whose titles highlighted the war’s human damage. Wounded Scout: A Friend in the Swamp (1864) reflected his interest in Union combatants and emancipation. The dominant figure is a tall escaped slave who steadies a White soldier with an injured right arm. A political message resides in a copperhead snake that, Rogers observed, raises “its head to strike the negro while he is doing his friendly act.” The artist sent a copy to Abraham Lincoln, who thanked him for the “very pretty and suggestive, and, I should think, excellent…piece of art.” Abolitionist Lydia Maria Child thought the sculpture offered “a significant lesson of human brotherhood for all the coming ages.” Among Rogers’ most popular pieces, Wounded to the Rear, One More Shot (1864) portrays two soldiers, one struck in the arm and the other in the leg. Ordered to leave the firing line, they have stopped to fire a last round at the Rebels. This tribute to Union courage proved a favorite with veterans. For Joseph R. Hawley, a division commander during the war and long-time senator from Connecticut, “Nothing relating to the war in painting or sculpture surpasses ‘One More Shot.’”

Several of the sculptures echo Winslow Homer’s treatments of daily life among Union soldiers. The Camp Fire: Making Friends With the Cook (1862) presents a seated soldier reading from a newspaper to an African American standing over a kettle. The two men’s body language suggests a comfortable familiarity across racial lines. The Town Pump (1862) places an infantryman holding a cup and a woman with a bucket beside a common well, evoking the plight of thirsty soldiers on the march, while Camp Life of the Card Players (1862) shows two bare-headed Zouaves who have re-purposed a large drum as their playing surface.

Most of Rogers’ audience would have interpreted the Black figures in Wounded Scout and The Camp Fire as contrabands—Civil War parlance for African American refugees. Union Refugees (1863) deals with displaced White Unionists in the Confederacy. The three-person grouping, comprising an obviously exhausted couple and their small boy, received considerable praise when exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1863.

Rogers devoted his last Civil War–related piece, titled The Fugitive’s Story, to emancipation. It served as an artistic bookend to The Slave Auction (1859), a commercial failure that nonetheless had garnered some national attention for Rogers. As in The Council of War, he chose three major historical figures for The Fugitive’s Story—in this case abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison, John Greenleaf Whittier, and Henry Ward Beecher. Grouped around a desk, the three listen to an African American woman, who holds her child and tells about escaping enslavement. The Independent, a New York weekly Beecher had edited early in the Civil War, reported that Sojourner Truth wept upon seeing Rogers’ treatment of an enslaved mother who had shepherded her child to freedom.

Truth’s response suggests the emotional appeal of Rogers’ sculptures. A photograph of George Armstrong and Elizabeth Bacon Custer at Fort Abraham Lincoln in the early 1870s includes Wounded to the Rear on one end of a small table and Mail Call on the other. Mrs. Custer’s Boots and Saddles (1885) mentioned “two of the Rogers statuettes that we had carried about with us for years….our attachment for those little figures, and the associations connected with them, made us study out a way always to carry them.” Close examination of Rogers’ Civil War sculptures helps illuminate why so many Americans joined Sojourner Truth and the Custers in linking the artist’s work to important elements of the conflict.