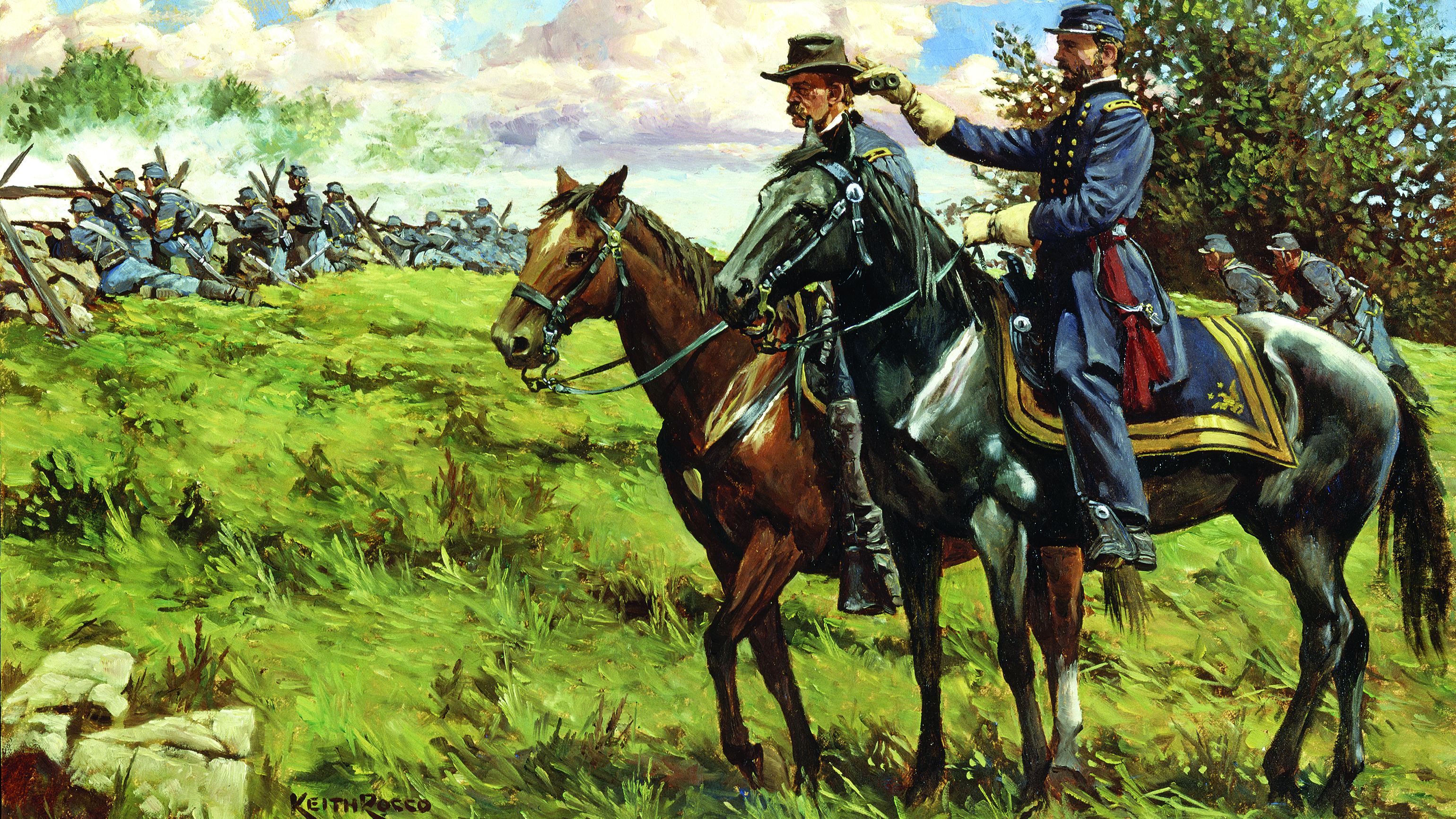

By sacrificing the 1st and 11th Corps, the doomed Union general gave Meade the edge he needed in July 2-3 fighting

IN OUR MEMORY of Gettysburg and the Union Army of the Potomac, it usually is assumed that Maj. Gen. John Reynolds was a great general with a sterling war record. Even back then, that seemed the case. “Reynolds was probably the most respected man in the Army of the Potomac,” writes John Hennessy, noting he attained that status “despite a combat record that included only one bright spot”—Second Bull Run, where he led a division. He had performed well as a brigade commander during the Seven Days, though captured after Gaines Mill. He was exchanged in time to fight at Second Bull Run but was detached during the Antietam Campaign—over his objections—to organize the Pennsylvania State Militia for the defense of the state. Upon his return, he was promoted to command the 1st Corps in place of wounded Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. His performance at Fredericksburg, though, was not particularly distinguished, and at Chancellorsville his corps played a relatively minor role.

[divider_flat]What seems to have impressed people about Reynolds was not his combat record but his competence. He also exuded confidence, which subordinates found infectious, and wasn’t public with his politics or his opinion of other officers. To his men, he was “one of the soldier generals of the army,” and though he and Hooker had a shaky relationship after Chancellorsville, Hooker said of Reynolds that during the opening stages of the Gettysburg Campaign, “I have never had an officer under me acquit himself so handsomely.”

Abraham Lincoln met privately with Reynolds on June 2, 1863. It is widely speculated that the president offered him command of the Army of the Potomac and that the general declined because he believed he wouldn’t have the freedom to act as needed. Whether that is true is irrelevant. The point is, Lincoln would not have met privately with a corps commander if he hadn’t respected him and valued his opinion.

As a general, Reynolds’ biggest test came on July 1 at Gettysburg. He was on the field there only briefly before he was killed, yet his actions that morning profoundly shaped the battle that followed. The question is whether he rose to the occasion or instead demonstrated that he was overrated and behaved recklessly in placing the army at risk.

On June 30, Reynolds was placed in command of the Left Wing of the Army of the Potomac, which included the 1st, 3rd, and 11th Corps. The assignment reflected the confidence army commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade had in Reynolds’ leadership and judgment. Reynolds’ orders for July 1 were to advance the 1st Corps to Gettysburg to support Brig. Gen. John Buford’s cavalry. Those orders contained a key provision: Reynolds had authority “without waiting for the enemy or further orders” to fall back toward Emmitsburg, Md., if he felt the situation warranted, but that “your present position was given more with a view to an advance on Gettysburg than a defensive point.”

Meade would revise his plans during the night and on July 1 issued a circular, now known as the Pipe Creek Circular, directing the army to defensive positions behind Pipe Creek near Taneytown, Md., if contact was made with the Confederates. Because of an unforseen delay, Reynolds never received the revisions.

Reynolds, who did not expect fighting on July 1, rode in advance of his troops to meet with Buford and examine the ground at Gettysburg. It proved a crucial decision. The first evidence that something was amiss was when civilians were encountered fleeing south on the Emmitsburg Road, describing fighting ahead.

When he soon learned the Rebels were advancing on the Chambersburg Pike, Reynolds hurried to the Lutheran Seminary, west of town, and found Buford. We do not know precisely what the cavalryman told the general, but it is possible to surmise it from his report and dispatches. His outposts were being driven in by A.P. Hill’s Corps, James Longstreet’s Corps was in Hill’s rear, and Richard Ewell’s Corps was north of Gettysburg.

This meant that up to 60,000 Rebels were approaching on the pike, with 30,000 more north of town. Reynolds had only a 3,500-man division within an hour’s march. The rest of the 1st Corps would not arrive before 11 a.m.; the 11th Corps not until early afternoon. He needed to make an immediate decision.

Reynolds’ orders offered him three options. First, he could withdraw Buford and the 1st Corps and concentrate them with the 3rd and 11th Corps above Emmitsburg—the safest option, though ceding the initiative to the enemy.

Second, he could have Buford screen the enemy advance and position the 1st and 11th Corps on and around Cemetery Hill. This high ground was the best defensive terrain in the area, but it put the Federals at risk if overwhelmed by the then-stronger Confederate force.

Third, he could engage the Rebels beyond Gettysburg, trading men for time. This was his riskiest option, but it kept up a screen of the key terrain south of town as well as the road network that would bring the rest of the army to the field. Reynolds chose this riskiest option.

Although Reynolds would pay with his life, subsequent events proved the wisdom of his audacity. He, not Lee, had chosen the battlefield, and the sacrifice of the 1st and 11th Corps let the rest of the army occupy Cemetery Ridge, Little Round Top and Culp’s Hill, giving Meade the edge in the July 2-3 fighting. Had the army followed Meade’s Pipe Creek Plan, the always dangerous Lee would have been accorded the initiative.

Reynolds, of course, should not be held up as the architect of Union victory at Gettysburg. Many, including Meade, deserve a share of the credit for that. But in his brief time on the field, the general resoundingly answered the question of whether he deserved the confidence and trust that people such as Meade, Lincoln, and others had in him, and, we might add, his place in the battle’s history.

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.