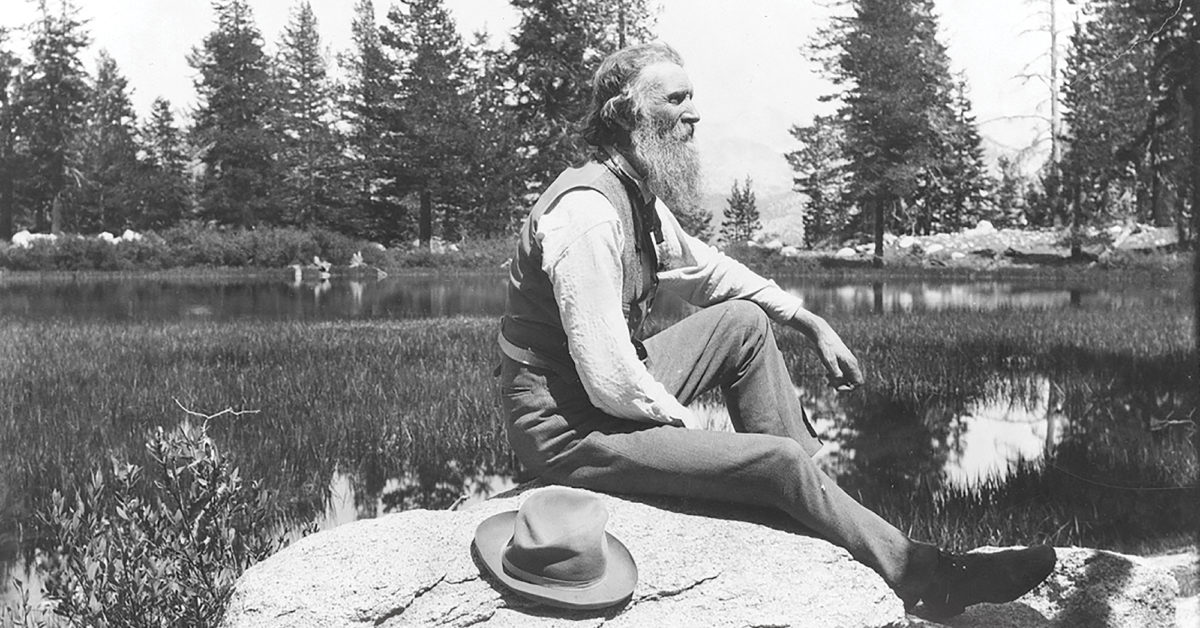

The storm chased John Muir down Mount Shasta in northern California. With clouds wheeling overhead, he descended from the summit as fast as possible. Even so, he’d barely reached the tree line when the first flakes fell—skirmishes before an onslaught of freezing snow. Having lived to the ripe old age of 36, Muir had been in such fixes before. In a frenzy of energy, he gathered wood and coaxed a fire to life. As he’d neglected to bring a tent, the Scot cozied up to the lee side of a log and went to sleep on a pile of leaves. The storm burst around him.

Though he’d initially set out on a day trip, Muir spent that second night on the mountain in early November 1874 listening to the tones of the wind, catching snow crystals and examining them under a lens. He awoke covered in snow. Instead of tramping directly down the mountain, however, Muir determined he would spiral around it.

“By this time I began to feel a little ‘gone’ from lack of food,” Muir recalled. “I’ve often spent two days without anything to eat and even felt better for it; but the third day is getting toward the point of being too much.”

Fortunately, Muir spied a plume of smoke. Working toward it, he came across a party of Mexican sheepherders and conveyed through gestures he was starving. The generous Mexicans prepared a meal for Muir and invited him to share their camp. In the morning they gifted him bread and coffee and bade him adios. For the next three days Muir continued hiking. On the seventh day he completed his circuit of Mount Shasta and strode into Strawberry Valley (site of the present-day city of Mount Shasta). Around noon he reached Sisson’s Tavern.

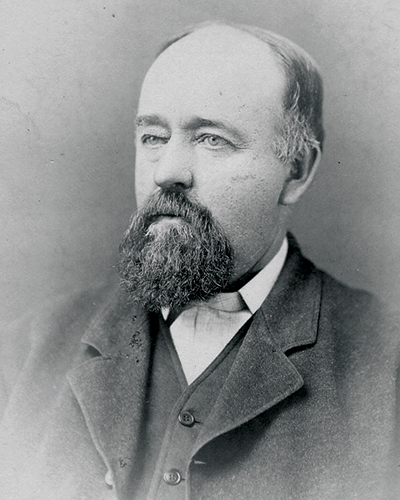

The tavern, which doubled as an inn, was owned and operated by Justin Sisson and wife Lydia. Seven days earlier—before embarking on his spur-of-the-moment, 120-mile ramble—Muir had told Lydia he wouldn’t be gone long and to expect him back for lunch.

Spotting Muir, Lydia hailed her overdue guest. “Well, Mr. Muir,” she asked, “do you call this a short walk? Where have you been?”

Having summited and circumnavigated the 14,179-foot mountain while surviving on coffee, water and bread, the intrepid Scottish-American naturalist seemed able to endure any hardship. Muir’s next ascent of Shasta would test that assumption.

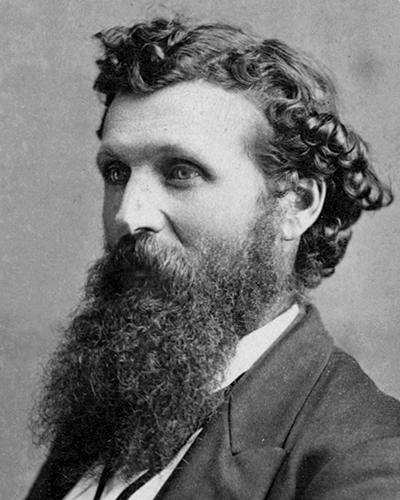

On April 29, 1875, Muir and fellow mountaineer Jerome Fay left Sisson’s Tavern bound for Mount Shasta toting blankets and a day’s worth of food, water and coffee. Their ascent had a scientific purpose—to make barometric observations at the summit while Captain Augustus F. Rodgers of the U.S. Coast Survey took readings at the base. Clad in his shirtsleeves, Muir was not as prepared for weather as the jacketed Fay, but without a cloud in the sky he felt little anxiety. Muir also had faith in Fay, whom he considered “a hardy and competent mountaineer.”

Born on March 3, 1838, in Chittenden County, Vt., Fay had journeyed to California in 1858 on a sheep and cattle drive. In 1870 he herded stock for rancher Josiah Edson in Gazelle. After moving 20 miles southeast to Strawberry Valley and partnering with Jerome Sisson, Fay tended bar at the tavern and guided climbing parties up Mount Shasta. It was in that capacity Fay met Muir, who was his junior by scarcely a month.

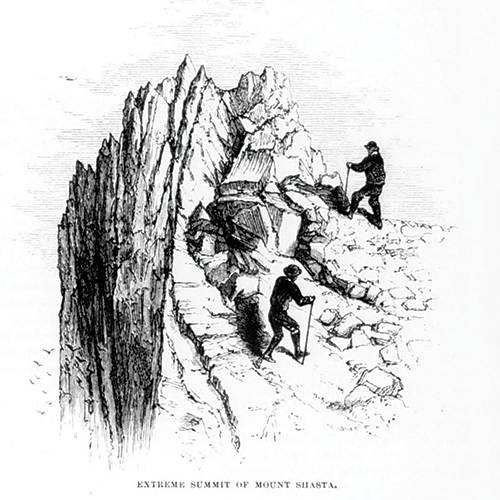

At midnight Muir and Fay lit a fire and made camp at the extreme edge of the timberline on a slab of red igneous volcanic rock Muir recognized as trachyte. After grabbing two hours of shallow sleep, they brewed coffee and broiled a slice of frozen venison on the coals. At 3:20 a.m. they set out.

“The crisp, icy sky was without a cloud,” Muir recalled, “and the stars lighted us on our way. Deep silence brooded the mountain, broken only by the night wind and an occasional rock falling from crumbling buttresses to the snow slopes below. The wild beauty of the morning stirred our pulses in glad exhilaration.”

The view was spectacular. To the northeast they could see Klamath and Rhett (present-day Tule) lakes and the lava beds (present-day Lava Beds National Monument) where two years earlier the U.S. Army had fought Kintpuash (aka “Captain Jack”) and his band of Modoc Indians. To the north yawned Shasta Valley. To the east and west dark coniferous forests carpeted lesser peaks. To the south rose the southernmost peak in the Cascade Range—10,457-foot Lassen Peak—around which “several hundred square miles of white cumuli spread out on the lava plain…squirming dreamily in the sunshine far beneath and exciting no alarm.”

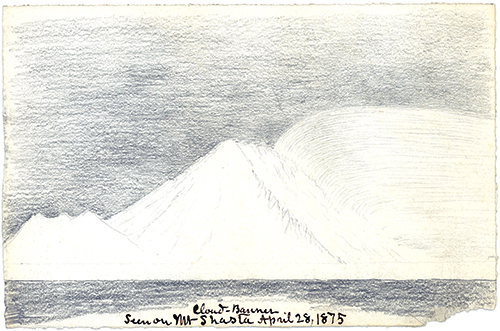

After resting from their climb, Muir and Fay took readings. At 9 a.m. the thermometer registered 34 degrees in the shade. Four hours later, while a venturesome bumblebee buzzed about their heads, the mercury topped out at 50 degrees. As the wind picked up, Shasta Valley filled with clouds, eclipsing the distant lakes. Meanwhile, the clouds that had gathered around Lassen Peak drifted northward. Soon the banks merged, circling Shasta in an eerie white blanket. From their lofty perch Muir and Fay recognized the gathering clouds for what they were—the stirrings of a snowstorm.

‘The wild beauty of the morning stirred our pulses in glad exhilaration’

John Muir

“It began to declare itself shortly after noon,” Muir recalled, “and I entertained the idea of abandoning my purpose of making a 3 p.m. observation, as agreed on by Captain Rodgers and myself, and at once make a push down to our safe camp in the timber.”

A spring day that had begun with such promise had transformed into a wintry nightmare.

Just beyond the thermal area Muir halted beneath the shelter of a giant block of trachyte to let Fay catch up. Ahead of them was the perilous snow ridge, where a single misstep could prove fatal. Despite the howling wind, blinding snow, lightning and deepening gloom, Muir still believed they could negotiate it. But Fay cautioned against the attempt. Even if they could grope their way through the stygian darkness, he explained, the wind would surely hurl them into the void. Muir thought otherwise, but Fay wouldn’t budge. Although not convinced, Muir decided not to leave his friend, even if it meant freezing to death.

But Fay had a plan. He dashed from the lava block—struggling 20 or 30 yards through the storm as if caught in a flood—to the thermal area. Muir was compelled to follow.

“Here,” Fay said, as they shivered amid the sputtering and hissing fumaroles, “we shall be safe from the frost.”

“Yes,” Muir said, “we can lie in this mud and gravel, hot at least on one side. But how shall we protect our lungs from the acid gases? And how, after our clothing is saturated with melting snow, shall we be able to reach camp without freezing, even after the storm is over? We shall have to await the sunshine. And when will it come?”

With no other option, the mountaineers lay on their backs in the scalding muck, Fay in his coat, Muir in shirtsleeves. Weak from exhaustion, they shivered uncontrollably as the freezing wind tore at their exposed skin and the scalding steam cooked their backsides.

A spring day that had begun with such promise had transformed into a wintry nightmare

As the night deepened, 2 feet of snow piled on Muir and Fay. At first they were glad for the snow, hoping it would buffer them from the freezing wind. But as the snow froze to their skin and slipped into the hollows of their clothing, their misery only magnified. The snow fell for two hours before subsiding. “The clouds broke and vanished, not a snowflake was left in the sky, and the stars shone out with pure and tranquil radiance,” Muir marveled.

But the winds did not cease. Bereft of strength, the mountaineers resigned themselves to a miserable night covered in snow and icicles, while they boiled from beneath. To stand up and expose themselves fully to the wind might have proved fatal. But the fumaroles posed their own hazards. When the heat became unbearable, Muir and Fay stuffed the vents beneath them with snow and trachyte, or shifted position by crab walking on their heels and elbows. As they shifted about, the incrustations often gave way, exposing concealed vents and scalding them anew. Muir worried that if the wind were to suddenly die, they might inhale excessive carbonic acid and fall into a sleep from which they would never wake.

Bereft of strength, the mountaineers resigned themselves to a miserable night covered in snow and icicles, while they boiled from beneath

“I warned Jerome against forgetting himself for a single moment, even should his sufferings admit of such a thing,” Muir reflected. “Accordingly, when, during the long dreary watches of the night, we roused suddenly from a state of half consciousness, we called each other excitedly by name, each fearing the other was benumbed or dead.”

Muir also tried to coax Fay into sharing tales about Indian encounters or bear hunting. But his companion was in no mood for storytelling. Instead, Fay obsessed over how long the storm might last, whether Justin Sisson would attempt a rescue, and just how long they could possibly last in that hellhole. Muir tried to cheer them both by insisting that no spring storm on Shasta lasted more than a day, and that one day Fay would be able to regale family and friends with stories of this wretched night.

At some point Muir and Fay began to hallucinate, imagining resiny pine logs from which they could build a fire. In the night sky Muir could make out Ursa Major, but the heavens soon took on a life of their own. Every planet seemed visible, glowing with lances of light like blossoming lilies close enough to touch. Even the ground thousands of feet below them became discernible. Frozen, burnt, starved, and oxygen- and sleep-deprived, Muir and Fay swore they could actually see the secluded valleys, haunts of the bear and deer, and tall brown fir trees with fernlike branches and trunks spotted with orange lichen. Then the banshee wind would sweep down with a flurry of snow, shattering the mirage, and the pain of reality would settle in.

“Muir?” Fay asked, his voice faint. “Are you suffering much?”

“Yes,” Muir replied, struggling to keep a lightness to his voice. “The pains of a Scandinavian hell, at once frozen and burned. But never mind, Jerome; the night will wear away at last, and tomorrow we go a-Maying, and what campfires we will make, and what sunbaths we will take!”

In such a manner Muir and Fay passed the night. Some 13 hours after having lain down amid the fumaroles, light touched the peaks. But as the cloudless May day dawned, and the wind abated, the mountaineers felt no warmer. They decided to wait till the sun was higher to stir and begin their descent. At about 8 a.m. on May 1, seventeen hours into their ordeal, they finally stood. Their feet and trousers were frozen. Though he’d survived the fury of the storm without a coat, Muir’s left arm was benumbed and useless. But he wasn’t overly worried. He knew mountaineers held a secret reserve of energy he called the “second self” that they could tap in an emergency.

Summoning those last reserves of strength, Muir and Fay began their descent. They found that the moaning wind had swept the treacherous ridge of almost all snow, making it easier to traverse. Once beyond it the pair made rapid if inelegant progress, shuffling through and sliding across the fresh snow. Lacking the ability to catch themselves, they lurched inexorably forward. After descending 3,000 feet, the mountaineers began to feel the reviving warmth of the sun.

At 10 a.m. their camp came into view. A half hour later they heard Sisson shouting through the firs. Concerned by their conspicuous absence, the tavernkeeper had determined to ride to their rescue. Moments later he burst into sight, leading fresh horses. Although starving, Muir and Fay desired hot coffee more than anything. That Sisson happily provided. Then, after a two-hour descent, the horseback trio emerged dreamlike on a trail festooned with violets, lilies and larkspur. At 4 p.m. they finally reached Strawberry Valley and Sisson’s Tavern, where Muir and Fay promptly collapsed into a deep sleep.

The next morning Muir awoke to sunbeams pouring through the window of his room. In the distance he could see Shasta—on whose summit he and Fay had survived a Scandinavian hell—crowned with trees and clouds.

“How fresh and sunful and newborn our beautiful world appeared!” Muir recalled. “Sisson’s children came in with wildflowers and covered my bed, and the sufferings of our long, freezing storm period on the mountaintop seemed all a dream.”

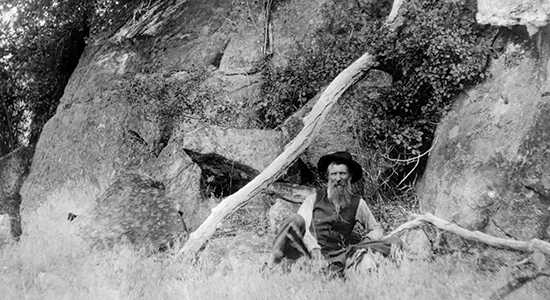

Muir went on to have many more adventures and gain renown as “Father of the National Parks.” In his old age he developed a slight limp he attributed to that sleepless night on Mount Shasta. He also credited Fay with having saved his life by refusing to attempt a descent amid the blizzard. In 1880 Fay married Lucy Edson, a sister of the rancher for whom he’d worked in Gazelle. Sadly, she died two years later at age 46. For the rest of his life the mountaineer regaled listeners with the adventures he and Muir had shared in the wilds of California. On Dec. 28, 1912, 74-year-old Fay died of heart failure aboard a passenger car in Redding as his train left the station. His ashes are buried beside those of his beloved Lucy at the roadside Foulke Cemetery just south of Gazelle.

Matthew Bernstein, when not rambling through the California wilderness, teaches at Matrix for Success Academy and Los Angeles City College. For further reading he recommends A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir, by Donald Worster, and The Wild Muir: Twenty-two of John Muir’s Greatest Adventures, selected and introduced by Lee Stetson.