Adam Sakowitz is a young man with a mission. The 25-year-old graduate student from Westbury, N.Y., is leading an effort to honor Senator John Glenn, who died on December 8, with a series of tangible memorials in Glenn’s home state of Ohio. Sakowitz hopes these will include a statue on the Ohio Statehouse grounds, historical markers at sites associated with Glenn’s life, recognition of his birthplace home in Cambridge on the National Register of Historic Places and eventually a museum dedicated to the former U.S. Marine Corps pilot and astronaut.

Glenn has been Sakowitz’s personal hero since 1998, when as a second-grader he watched the 77-year-old senator return to space aboard the shuttle Discovery. Glenn, of course, is best known as the first American to orbit the earth, in the Mercury capsule Friendship 7 on February 20, 1962. “My grandparents were at the tickertape parade for Glenn in 1962,” says Sakowitz, and they brought back buttons and other mementos that they later shared with him. He says Glenn’s space shuttle flight, during which he became the oldest person ever to fly in space, “had a tremendous impact on me.”

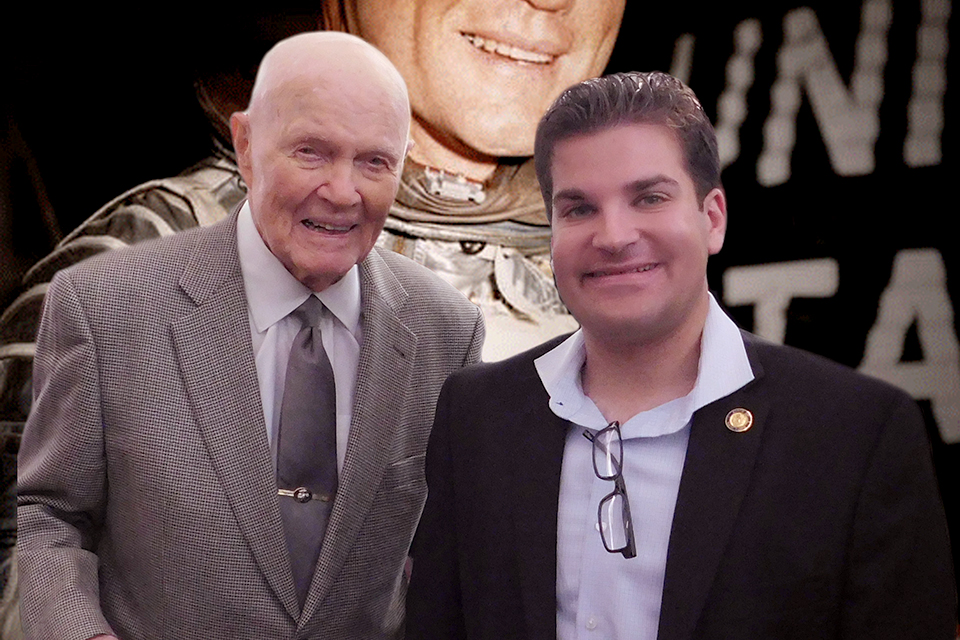

Currently pursuing a master’s degree in history at St. John’s University in Queens, Sakowitz notes: “I had the great privilege of meeting Glenn several times, the first in 2014. He was extremely humble, a good listener. Some of our conversations were remarkable.” He asked Glenn why he thought Ohio became a leader in aviation, with native sons such as the Wright brothers and Neil Armstrong. “He said Ohio had a pioneer spirit and tradition of rugged individualism,” qualities that helped foster an environment of creative thinking and experimentation among the state’s early aviators, and later led 24 Ohio natives to become astronauts.

While Glenn’s service as an astronaut and U.S. senator is well known, his time in the Marine Corps has garnered less attention. After earning his pilot’s certificate in July 1941 under the Civilian Pilot Training Program, Glenn enlisted in the Army Air Corps following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. When he wasn’t called up, Glenn enlisted as a naval aviation cadet, and later transferred to the Marine Corps. He flew 59 combat missions in F4U Corsairs in the Pacific, and went on to fly 90 combat sorties during two Korean War tours.

Sakowitz thinks those early years in combat informed Glenn’s later attitudes toward nuclear proliferation—the theme of a graduate paper he recently prepared. “These men who came back from World War II lost friends and saw the horrors of war,” he explains, “and their experiences changed them for the rest of their lives.” In his paper he cites two incidents in particular that profoundly affected Glenn: the loss of his good friend and wingman 1st Lt. Miles F. Goodman Jr. to anti-aircraft fire on July 9, 1944, and a mission that December in which he dropped a new weapon—napalm—for the first time. Of the former Glenn wrote in his autobiography, “…war had suddenly become very, very personal”; of the latter, “It was terrible to think what it was like on the ground in the middle of those flames.”

“I had been through World War II and Korea and knew what happens in conventional war,” Glenn wrote. “The horror of a nuclear holocaust was beyond imagining.” As a senator, that belief led him to become the chief architect of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act of 1978.

“Our country’s young people could learn so much from John Glenn,” says Sakowitz. To read his research paper, “A Soldier Prays for Peace,” click here.