On the afternoon of December 7, 1941, director John Ford and his wife were attending a luncheon at the home of Rear Admiral Andrew C. Pickens in Alexandria, Virginia. The host excused himself to take a call from the War Department. When he returned, he told his guests that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. “We are at war,” he said.

Ford was ready.

He had been born John Martin Feeney in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, on February 1, 1894, the son of Irish immigrants who had settled in nearby Portland, where the elder Feeney operated a bar. Young John played on the Portland High School football team and graduated in 1914. His high school nickname, probably because of his football prowess, was “Bull.”

When Feeney’s older brother Francis headed west and found work as an actor and director in California, young John followed—and assumed his brother’s stage name of Ford as well. Eventually John Ford began directing his own films. By the time of Pearl Harbor he was one of Hollywood’s most respected directors, with a resume that included The Iron Horse (1924), Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), How Green Was My Valley (1941), and even a Shirley Temple film, Wee Willie Winkie (1937). In his 1939 Western Stagecoach, Ford turned a relatively obscure actor named John Wayne into a star. That was also the first movie Ford shot in the Southwest’s Monument Valley, a setting he made iconic in his postwar Westerns.

Yet for all his talent, John Ford was a flawed human being with a strong streak of pure New England cussedness. “Actors were terrified of him because he liked to terrify them,” said John Carradine, who acted for Ford in several films. “He was a sadist.” Ford became known for the way he needled his actors, especially Wayne, during filming and for his tendency to go on drunken benders between projects. According to one acquaintance, “It was as though God had touched John Ford at the beginning of his life and said, ‘How would you like to be a very unique man—like no one else. However, you may scare some people.’”

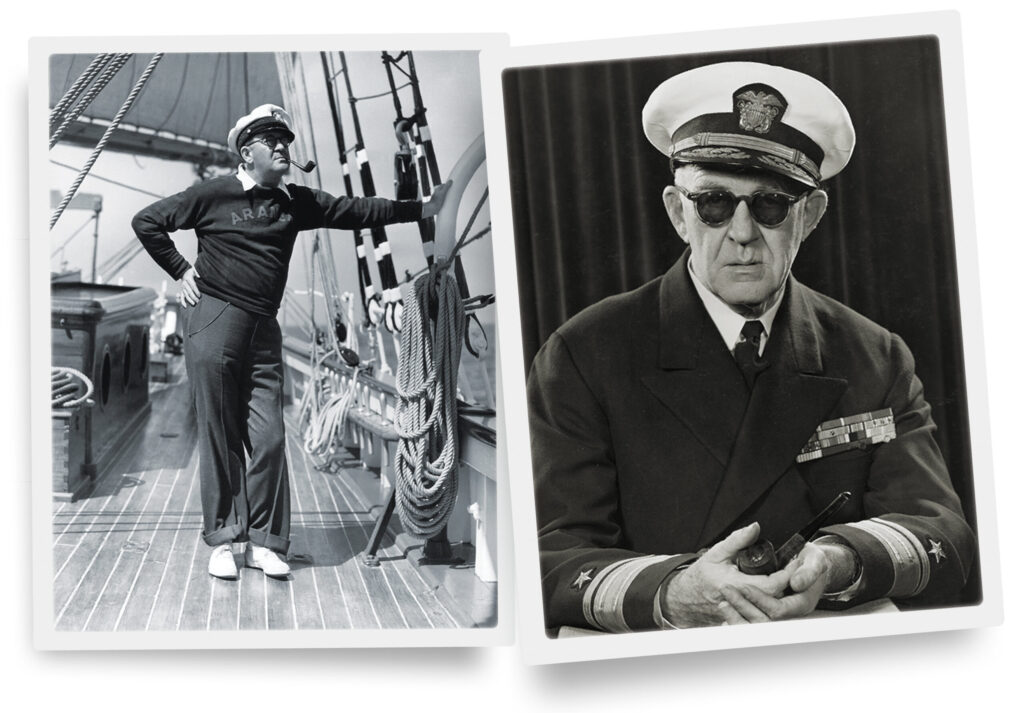

Ford had always nursed a love for the sea, perhaps inspired by his youth on Maine’s Casco Bay. In the 1930s he enlisted in the Navy Reserve with a commission as a lieutenant commander, and as tensions with Japan increased, he sometimes used his yacht Araner to shadow any Japanese vessels he encountered off the California coast. He started the Eleventh Naval District Motion Picture and Still Photographic Group in 1939 as a means of documenting the navy’s activities in the impending war and began recruiting friends from all aspects of the film industry to help. As he later said, “They are writers, directors, some actors, but mostly technicians, electricians, cutters, sound cutters, negative cutters, positive cutters, carpenters, and that sort of thing.” The navy called the 47-year-old Ford to active duty in September 1941 as a lieutenant commander and he went to Washington, where his photographic unit was assigned to work under William J. Donovan, the head of the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency.

In his new role Ford visited Iceland and Panama to survey the military situations there. After the attack on Pearl Harbor he received orders to head to Hawaii to film the aftermath. He and a crew embarked on the trip west on January 4, 1942. Twelve days later he was at Pearl Harbor, which he found “in a state of readiness. The Army and the Navy, all in good shape, everything taken care of, patrols going out regularly, everybody in high spirit[s]…”

On April 18, 1942, Lt. Col. James Doolittle and his raiders took off in twin-engine B-25 Mitchells from the carrier USS Hornet to bomb Tokyo. Although the Doolittle Raid did little physical damage to Japan, it dealt a psychological blow. Shocked by the American attack on its mainland, the Japanese military decided to move aggressively across the Pacific to prevent any more raids. One of its targets was a tiny atoll with an airstrip 1,110 miles northwest of Hawaii called Midway. It was little more than a speck in the vast Pacific, populated mostly by a species of albatross that people called gooney birds, but Midway was also the U.S. Navy’s westernmost base and home to a Marine detachment. Pan American World Airways had used Midway as a base for its Clippers, and navy submarines fueled there, too. A pair of Japanese destroyers had shelled Midway on the night of December 7, 1941, and the Japanese speculated that perhaps Doolittle’s men had taken off from the atoll for their attack. Furthermore, Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the mastermind behind the Pearl Harbor attack, believed that if he threatened Midway, he could draw the U.S. Pacific Fleet under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz out from Hawaii and into battle.

The U.S. Navy had cracked Japanese codes and knew that Midway was in the crosshairs, and Nimitz wanted Ford to photograph the fighting once it erupted. Sometime in late May 1942 he summoned Ford to his office at Pearl Harbor, said he had a dangerous assignment for him, and told him to report to Admiral David W. Bagley. Ford and cameraman Jack Mackenzie Jr. were soon zipping across the harbor in a speedboat for a rendezvous with a destroyer that was already underway. “Hadn’t the slightest idea what I was doing, where I was going,” Ford said. “I found out when I got on board the destination was Midway.”

All was quiet on Midway when Ford and Mackenzie arrived. “All the year around it’s the same out there on that little Pacific island,” Mackenzie told American Cinematographer magazine. “The grandest place in the whole ocean to find absolute quiet and peace—if that’s what you want.” Ford spent time photographing the island’s gooney birds and the PT boats that had accompanied the task force. He remained doubtful that the Japanese would really attack but, forewarned by the codebreakers, the navy had been scrambling to bolster the atoll’s defenses by flying in more aircraft and reinforcing the ground forces. “By June 4 there were 121 combat planes, 141 officers and 2,886 enlisted men on the atoll,” noted Samuel Eliot Morison in his history of naval operations during the war.

On June 3, Ford said, Commander Massie Hughes invited him aboard a PBY Catalina flying boats for a patrol. At first they saw nothing, Ford claimed, but then they got a glimpse of enemy vessels through a break in the clouds. When a couple of Japanese airplanes appeared to spot the PBY, Hughes headed into the clouds, and then descended for a wave-hugging return to Midway.

Something, Ford realized, “was about to pop.” Another Catalina spotted what appeared to be the Japanese invasion fleet and the commander of Naval Air Station Midway, Captain Cyril T. Simard, sent out B-17s and Catalinas to attack the vessels, with little result. Simard expected the Japanese to attack the next morning and suggested that Ford place himself on top of the powerhouse, where he would have a good view of the impending action as well as a telephone link to headquarters. Ford and Mackenzie set up and went to bed.

Simard was right about the attack, although the morning of June 4 started off calmly enough. “Everything was very quiet and serene,” Ford said. He and Mackenzie shared the powerhouse with some Marines who had also stationed themselves on the roof. The filmmakers had a pair of 16mm cameras loaded with color film. Sometime around 6:30 that morning Ford was scanning the sky with binoculars when he spotted the first black dots that meant incoming Japanese aircraft. There were 108 airplanes in all, including 36 Nakajima B5N “Kate” bombers, 36 Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers, and 36 Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” fighters, and they had been launched from four carriers about 200 miles out to sea. Midway’s radar had already picked them up and the defenders were braced for the onslaught. “Everybody was very calm. I was amazed, sort of, at the lackadaisical air everybody took,” Ford said. It was as though this kind of thing happened all the time.

The Japanese planes roared in to attack. According to Ford, the lead pilot shocked everybody by flipping his Zero on its back and flying upside down about 100 feet off the ground in a show of bravado. “Everybody was amazed, nobody fired at him, until suddenly some Marine said, ‘What the Hell,’ let go at him and then shot him down,” said Ford. “He slid off into the sea.”

Then the attack started “in earnest.” Bombs exploded nearby, shaking the cameras. A plane dropped a bomb on the garrison’s hangar, which exploded. A piece of concrete struck Ford in the head and briefly knocked him out. “Just knocked me goofy for a bit, and I pulled myself out of it.” Recovering, Ford continued to film despite also receiving an ugly, three-inch shrapnel wound in his arm.

Mackenzie, who kept a lucky rabbit’s foot in his pocket, had also been knocked down by the blast, and he regretted missing a shot of the explosion because he had been reloading film when it happened. He recovered and scrambled down a ladder to the ground and resumed shooting. “By this time [the Japanese] had riddled the hangars and set them on fire,” he recalled. “The hospital too was smashed and on fire, and the commissary was all busted up and burning fierce and one of our oil tanks was on fire sending a plume of heavy black smoke up into the atmosphere. It was a merry little hell all around.”

It appeared to Ford that the Japanese avoided bombing the runway, perhaps, he thought, because they hoped to capture the island and use it later. They did bomb alongside it, and they focused a lot of attention on an airplane the Americans had left out in the open as a decoy. From what Ford saw, the enemy wasted a lot of effort to destroy it. “[T]hey lost about three planes trying to get to that fake plane, as it came into a cone of fire that was pretty dangerous,” he said.

One incident that angered Ford happened as he peered through his binoculars and saw a Zero attack and kill a Marine who had bailed out of his airplane. “This kid jumped and this Zero went after him and shot him out of his harness,” he said, and then the Japanese pilot returned to strafe the water where the Marine had come down.

Ford told his debriefers how impressed he had been by the Marines around him. “They were kids, oh, I would say from 18 to 22, none of them were older. They were the calmest people I have ever seen. They were up there popping away with rifles, having a swell time and none of them were alarmed.” He added, “I was really amazed. I thought that some kids, one or two would get scared, but no, they were having the time of their lives.”

But not all of them had escaped with their lives. Forty-nine of the atoll’s Marine defenders had been killed. Their aircraft—F4F Wildcats and obsolete F2A Brewster Buffaloes—were outmatched by the Japanese Zeros, and attacks flown from Midway against the Japanese vessels proved inconsequential at best and resulted in the loss of more aircraft.

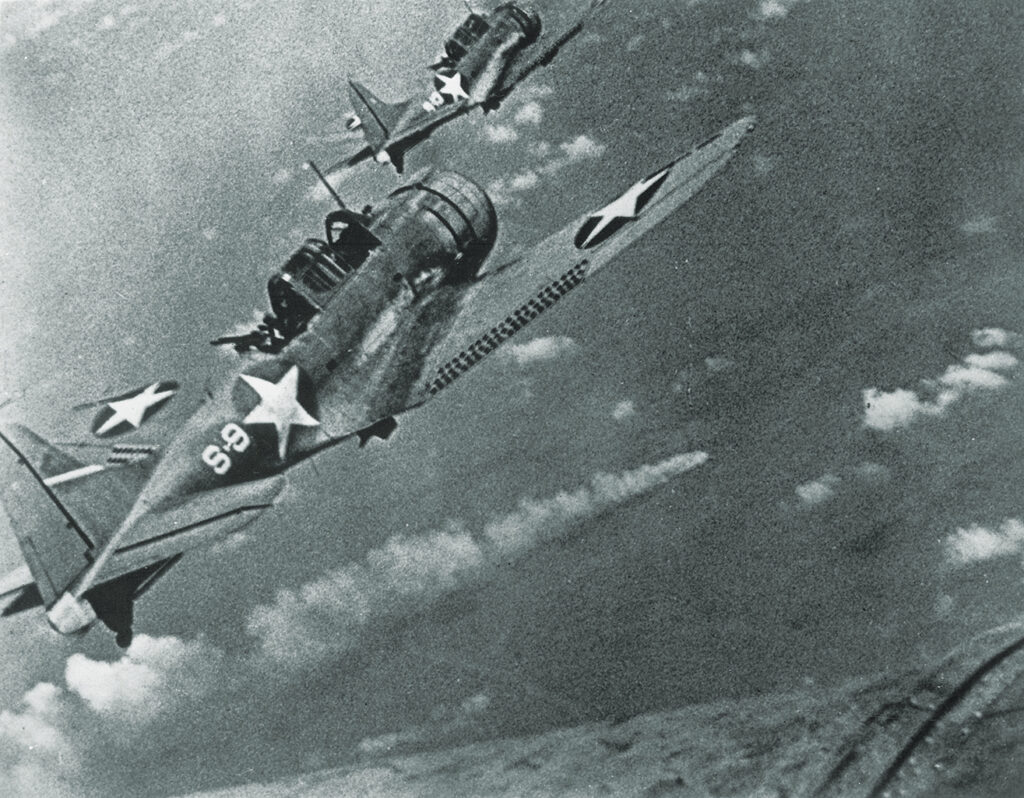

The attack on the atoll lasted only about 20 minutes. The Japanese did not return to follow it up with an invasion because they ran into difficulties out to sea. Yamamoto had accomplished his goal of drawing the Pacific Fleet into battle, but the results were not what the Japanese had desired. American carrier-based dive bombers pounced on the Japanese ships and sank four of its aircraft carriers—and one reason the American airplanes found the enemy ships at a disadvantage is because the carriers had to recover, refuel, and rearm the aircraft that had returned from the attack on the island. Although the U.S. lost the carrier Yorktown, the Battle of Midway at sea proved to be a disaster for Japan and a turning point in the Pacific war.

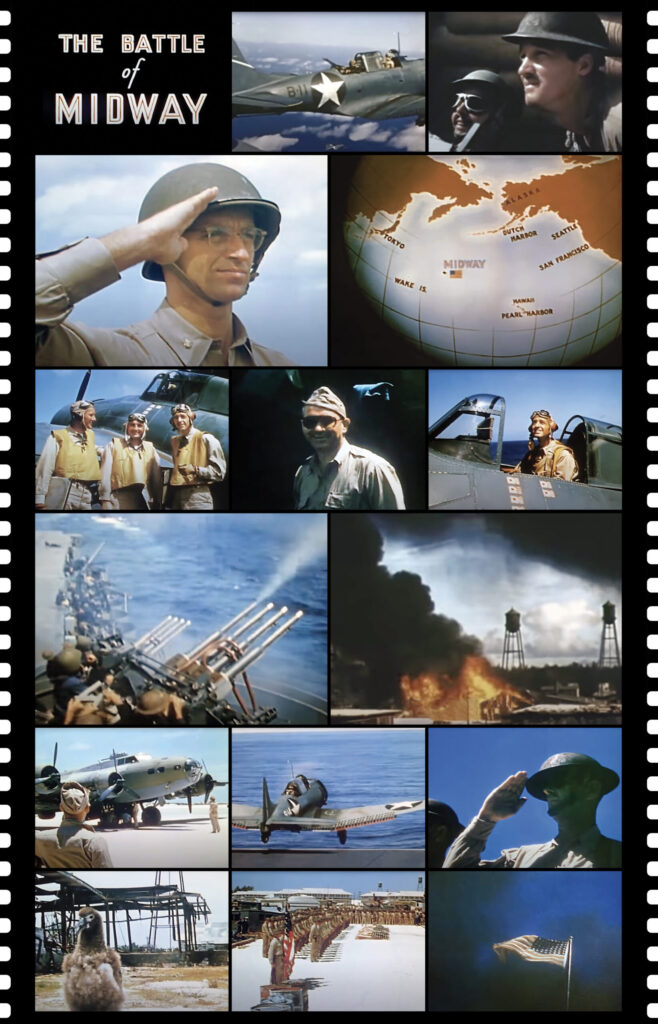

Ford returned to the United States with the raw footage from his small portion of the fight as well as footage shot by another of his cameramen, Lieutenant Kenneth M. Pier, who had been aboard the carrier Hornet at sea. He began shaping the footage into a short film with the assistance of some Hollywood friends—Henry Fonda and Jane Darwell from The Grapes of Wrath provided voices, Donald Crisp from How Green Was My Valley added narration, and Alfred Newman, who oversaw music for Twentieth Century-Fox, wrote the score. Ford insisted that his editors include a brief shot of Major James Roosevelt, the president’s son, in the final cut. If he did that to curry favor with Roosevelt, it worked. After screening the 18-minute short at the White House, the president told his chief of staff, “I want every mother in American to see this film.” The Battle of Midway began appearing in theaters, as a short before the main feature, in September. Critic James Agee called it “a brave attempt to make a record—quick, jerky, vivid, fragmentary, luminous—of a moment of desperate peril to the nation.”

“Even now, far removed from Midway and the war, The Battle of Midway resonates,” wrote Ford biographer Scott Eyman. “It remains one of Ford’s great achievements.”

Ford had a bumpier experience with another film from his unit. Cinematographer Gregg Toland had taken the lead in putting together a documentary about the Pearl Harbor attack, but the military men who previewed the work gave it scathing notices. They objected to the way the filmmakers had recreated events for their cameras, the film’s virulent portrayal of the Japanese, and the way it left the “distinct impression that the Navy was not on the job,” in the words of Admiral Harold Stark. Ford had it recut from 85 minutes to 34, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences voted December 7th best short documentary at the 1944 Oscars.

Ford continued his work for the navy. He ventured into harm’s way again in late 1942 when he oversaw shooting in North Africa. One person he encountered there was Darryl F. Zanuck, the production chief of Twentieth Century-Fox, for whom Ford had made The Grapes of Wrath and How Green Was My Valley. Zanuck had received a commission in the Signal Corps and was working on his own documentary. “Can’t I ever get away from you?” Ford grumbled to him. “I’ll bet a dollar to a doughnut that if I ever go to Heaven, you’ll be waiting at the door for me under a sign reading, ‘Produced by Darryl F. Zanuck.’”

Ford later went to Asia to film activity in Burma and China, and in June 1944 he supervised filming of the D-Day landings, activity marred when he went on an epic three-day bender in mid-June. Once he sobered up, Ford spent time aboard a PT boat commanded by John D. Bulkeley, who had rescued Douglas MacArthur from Corregidor in March 1942 and was the centerpiece of William Lindsay White’s book They Were Expendable, an account of PT boat crews in the Philippines. (See “Battle Films,” page 76.) When Ford returned to the United States to start work on the film version of White’s book, his time in the war zones were over.

After the war, Ford continued his film career, directing a series of classic Westerns with John Wayne. (Ford enjoyed needling Wayne over his lack of service in the military.) Those films included Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and The Searchers (1956). The director is now considered one of the great artists of Hollywood’s Golden Age. When filmmaker Orson Welles, no slouch behind the camera himself, was asked who his three favorite directors were, he answered “John Ford, John Ford, John Ford.”

For the rest of his days, until he died in 1973, Ford remained proud of his navy service and was “shameless” in his pursuit of official medals and ribbons. Befitting a man who had a character in one of his movies say, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” Ford often burnished the legend of his experiences at Midway and elsewhere. In truth, he had no need to embellish.