ONLY A LONE BLACK MAN stood between Max Schmeling and world domination. The German boxer was 30 years old and a veteran of some 60 bruising fights when he saw American heavyweight champion Joe Louis pulverize Spain’s Paulino Uzcudun in December 1935 at New York’s Madison Square Garden. There was no way, insisted reporters, that Schmeling could beat Louis—at 21, the most awesome boxer in living memory. Didn’t Schmeling know Uzcudun had collapsed in his dressing room after the fight? Sure, said Schmeling, he knew all right. “[But] I saw something which made me think I had a chance,” he later recalled. “Joe had a wonderful straight hand, but he’d punch and then sometimes drop it.”

With a fight against Louis scheduled for six months later, in June 1936, Schmeling returned to Berlin armed with films of Louis in action and obsessively played them over and over. While a confident Louis womanized in Hollywood and skipped training to play golf, Schmeling prepared diligently; the German was considered easy pickings for Louis as he punched his way into contention for for the world heavyweight title. Schmeling broke his strict training regime on one notable occasion, when invited to lunch with Adolf Hitler in Munich. Hitler was worried that Schmeling was going to lose to a member of an inferior race. Schmeling was, after all, taking on a formidable adversary, tagged as the “Brown Bomber” or the “Sepia Slugger,” who’d finished off five top boxers, including Uzcudun, Primo Carnera (Mussolini’s favorite), “Kingfish” Levinsky, Max Baer, and Charley Retzlaff in a total of just 16 rounds. Hadn’t Schmeling already been humiliated in 1933 by Baer—of all things a Jew?

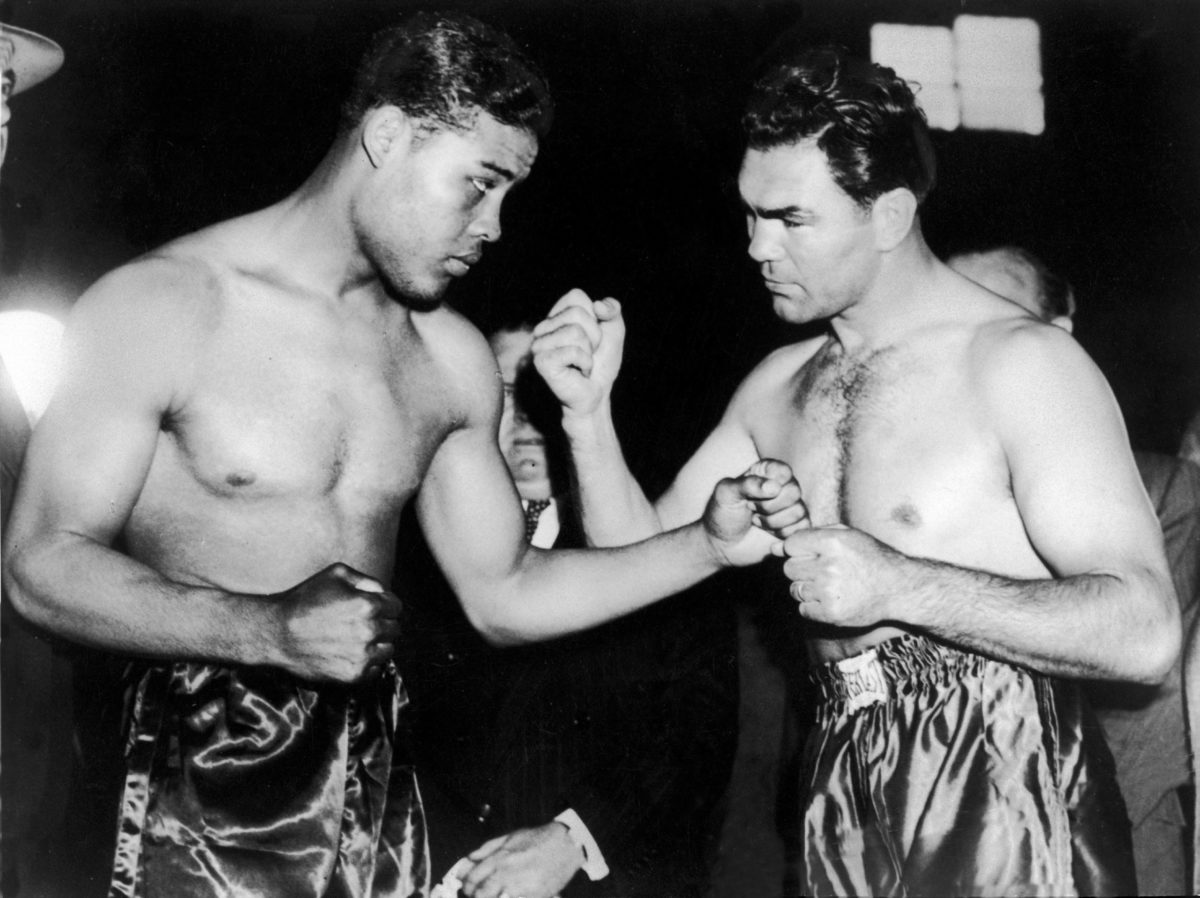

On June 19, 1936, Schmeling entered the ring in Yankee Stadium first, his glistening hair greased back above bushy brows. Within minutes, Schmeling showed that he had, after all, found Louis’s weakness. In the fourth round, sure enough, Louis dropped his guard. Schmeling hit him smack in the face. A split second later, Louis hit the canvas for the first time in his professional career.

Eight rounds later, Schmeling again caught Louis with a roundhouse right. Louis sagged to his knees and fell backward. The newsreels showed Schmeling leaping into the air in victory before a crowd of 45,000. Louis, the left side of his jaw badly swollen, didn’t leave his Harlem apartment for three days after his defeat, too humiliated to appear in public. “This stuff about Louis [being] the ‘dead-pan killer’ is so much bunk,” one smug reporter scoffed. “This 22-year-old Negro is made of much the same stuff as any other boy of his age. He proved it in the dressing room when he wept unashamed.”

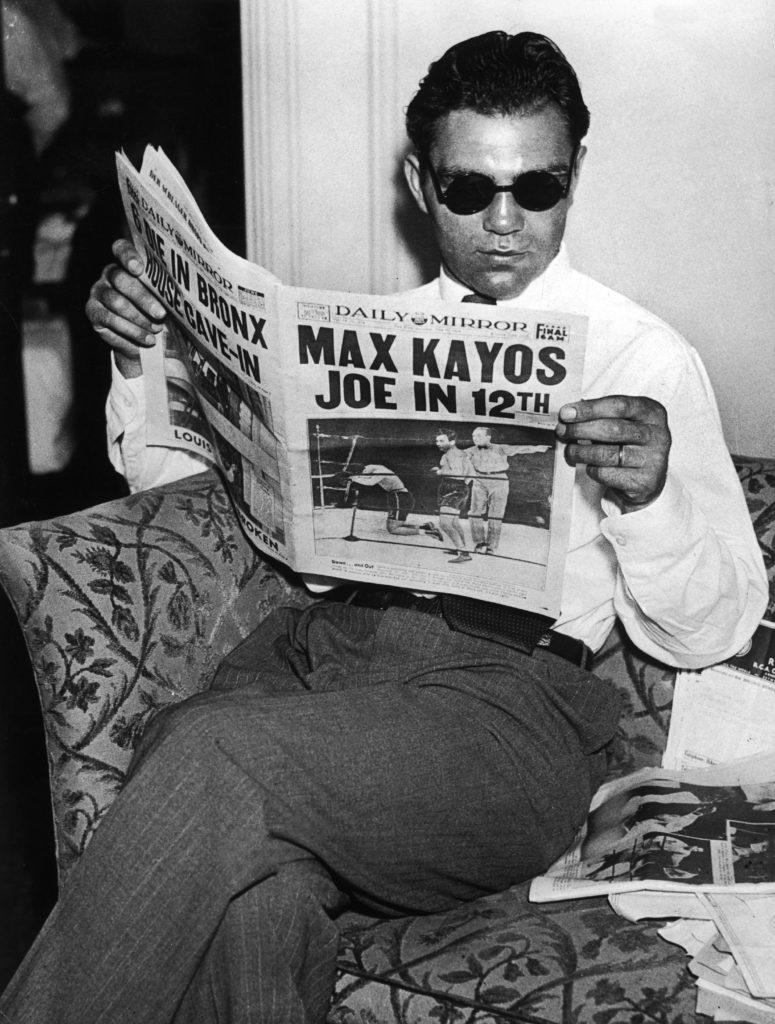

Black America grieved too. Their idol had fallen, defeated by “Hitler’s Heavyweight,” a member of the so-called master race. Some commentators even saw Louis’s defeat as a blow to the nascent civil rights movement. Schmeling later recalled the “hysteria and depression” he saw in Harlem as he was driven to his hotel after the fight. Back in Nazi Germany, Hitler was so delighted he sent a telegram: “Most cordial felicitations on your splendid victory.” Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels gushed: “I know that you have fought for Germany. Your victory is a German victory. We are proud of you. Heil Hitler and hearty greetings.”

When Schmeling arrived back in Germany, Hitler requested his presence. This time, the triumphant Schmeling brought his wife and mother to lunch with the Führer in Berlin. Hitler insisted on replaying Schmeling’s victory on film and slapped his thigh whenever Louis caught a punch. “Hitler was very interested in boxing,” Schmeling later recalled. “When we met, we did not speak about politics, only about the fight and the sporting situation. You have to remember the Berlin Olympic Games were due to start three weeks later. Of course, he was a devil. No question about it. And the whole system was rotten. But I couldn’t say Hitler was a beast when I met him. He was polite, charming.”

Yet, as with every other sports star in Nazi Germany, it was impossible for Schmeling to escape the shadow of National Socialism. Every matchup between a German and a rival from a democratic nation was increasingly politicized. Boxing in particular provided an ideal arena for opponents cast as representatives of rival ideologies. In knocking out Louis in 1936, Schmeling appeared to have added grist to Hitler’s fantasies of Aryan superiority. It was an association that would affect Schmeling—and Louis—for decades to come.

symbolic slugfest

A REMATCH BETWEEN Louis and Schmeling for the world heavyweight title was scheduled for June 22, 1938. Schmeling would be 32, Louis still only 24. But far more than age difference was now in play. Since the pair had last fought, the political climate had utterly changed. Nazi persecution of the Jews had increased, and Austria had been annexed. Europe teetered on the brink of war.

Judging by the American press, Schmeling was now Nazism personified. When he arrived in New York, a city he loved, police had to escort him to his hotel, where demonstrators shouted, “Boycott Nazi Schmeling.” As he walked along Fifth Avenue, passers-by gave him the Nazi salute. Throughout his stay in Manhattan, he received hate mail.

Four days before the fight, 18 American citizens were indicted on charges of spying for the Nazis—by which time President Franklin D. Roosevelt had already invited Joe Louis to the White House. “The politicization of sport which was pushed so hard by the Third Reich found a sort of echo on the other side of the Atlantic,” Schmeling recalled. “The one group came to emulate the other one, and this was bad for sport. At the time I was a young man with only the thought of a title fight in my head.”

Unlike many of his peers, Schmeling never joined the Nazi Party. He had no interest in politics. A proud German, he protested that he was, nonetheless, “no superman in any way.” He later added: “The unfortunate thing during the Thirties was that every German was seen as a Nazi. Even the people who were against Hitler.” Schmeling had refused to turn his back on Jewish friends in Germany, even after the enactment of the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which stripped Jews of German citizenship. Those friends included Dr. Kurt Schindler, who had accompanied him to New York for his first fight against Louis, and Paul Damski, a boxing promoter who had introduced Schmeling to the Czech film star Anny Ondra, whom Schmeling had married in 1933.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

comeback kid

THE DAY OF THE REMATCH was a humid Wednesday in New York. With a towel over his head, protected by a huddle of policemen, Schmeling was pelted with cigarette packs and paper cups as he made his way to the ring in the center of Yankee Stadium’s baseball field. Over a hundred million people around the world were listening to radio coverage. Among the 70,000 at the stadium, all seemingly on Louis’s side, were movie stars such as Clark Gable and Gary Cooper, eager to watch what promoters had termed the “Fight of the Century.”

Schmeling had entered the lion’s den. The crowd was so intimidating that “Doc” Casey, Schmeling’s American cornerman, dared not step into the ring. Yet Joe Louis faced perhaps even greater pressures. He had lost once to Schmeling. Defeat a second time was unimaginable to him. “Here I was, a Black man,” he later remembered. “I had the burden of representing all America. They tell me I was responsible for a lot of change in race relations in America…. White Americans—even while some of them were still lynching Black people in the South—were depending on me to K.O. Germany.”

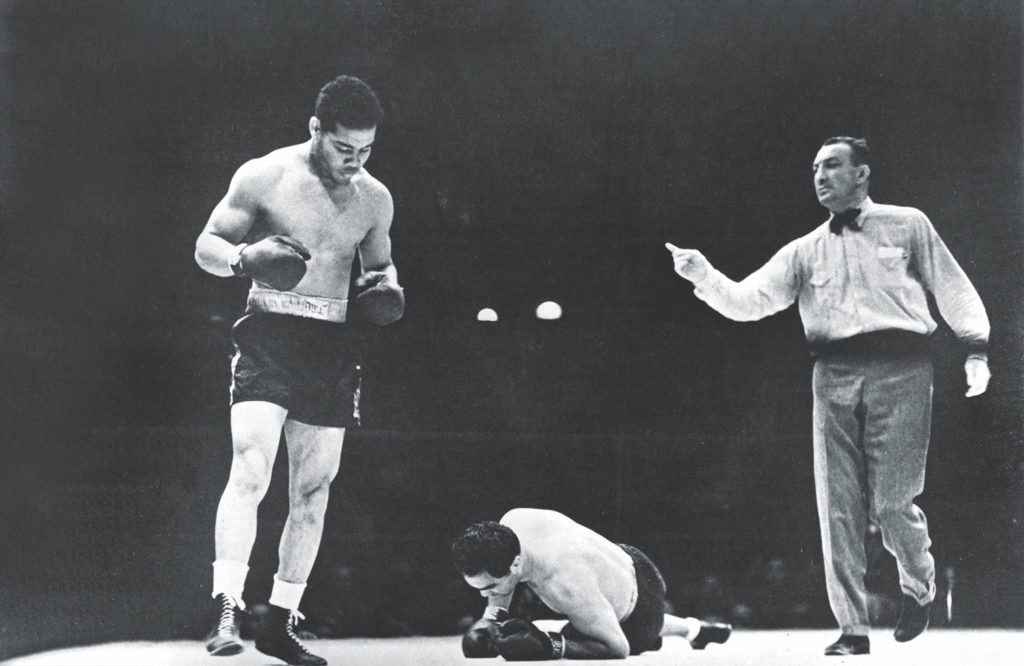

Louis, who took up boxing as a teen in Detroit, where he also worked at the Ford Motor Company, had learned the lesson of his 1936 defeat and opted to throw everything into the first rounds in the hope of out-punching Schmeling before the German’s technical skill could tell. His game plan worked. He had Schmeling on the ropes only a minute into the fight. Louis then jabbed to find his range and hit Schmeling with a right hook before smashing his fist into Schmeling’s left side, damaging a vertebra. Crying out in agony, the German went down but somehow got back on his feet, only for Louis to knock him down again. The referee began to count. By the time he reached “eight,” it was all over. Schmeling had lasted just 124 seconds of the first round.

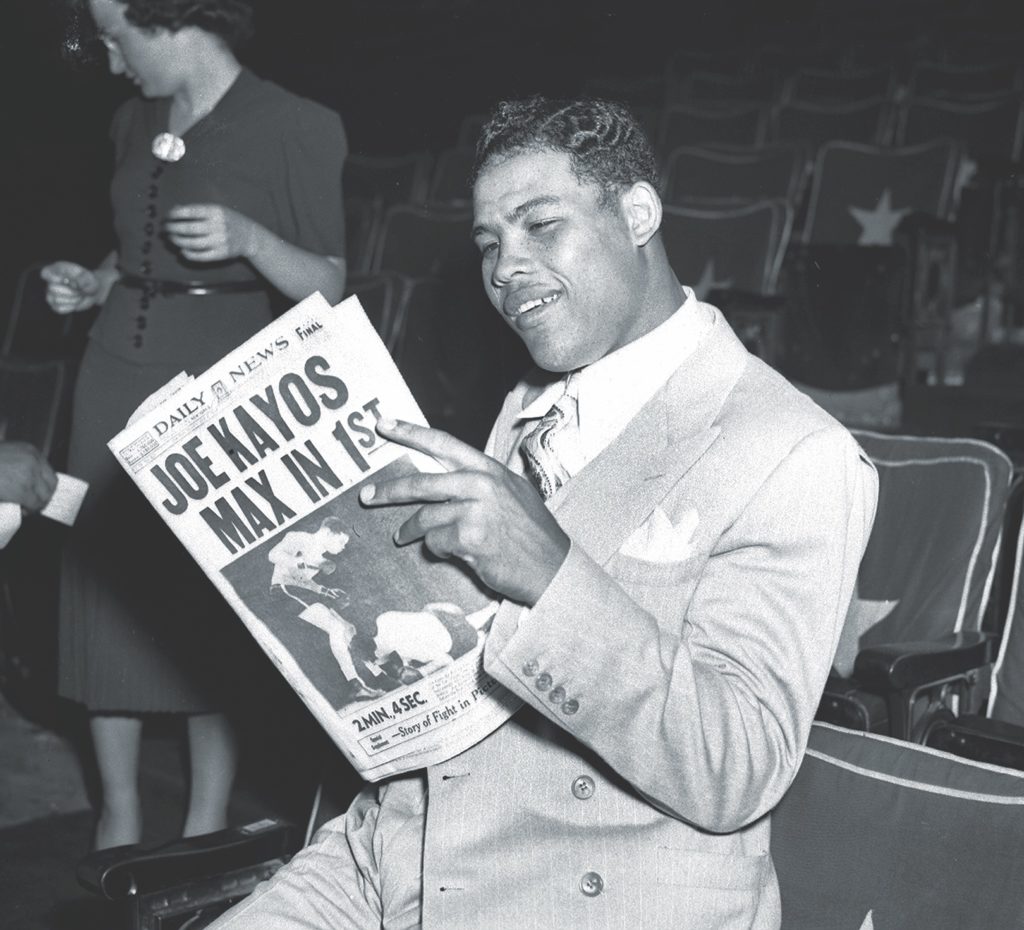

Louis’s victory set off delirious street parties in Black neighborhoods from Harlem to Oakland. It was as if Hitler himself had been laid out before a baying crowd. Heywood Broun, a journalist from the New York World-Telegram, wrote: “One hundred years from now, some historian may theorize, in a footnote at least, that the decline of Nazi prestige began with a left hook delivered by a former unskilled automotive worker.”

Schmeling’s name disappeared from the sports pages upon his return to Germany. There was no invite to sip tea with Hitler. Schmeling had, it seemed, discredited the master race. Only much later would he realize how the loss to Louis had a silver lining: “A victory over Joe Louis would have made me forever the ‘Aryan Show Horse’ of the Third Reich.”

Schmeling was protected to an extent by his celebrity and enormous popularity among ordinary Germans, and he used his fame cannily and at times honorably, refusing to drop his U.S.-based manager, Joe Jacobs, who was Jewish, much to Goebbels’s annoyance. During Kristallnacht, on November 9, 1938, as synagogues blazed and pogroms raged throughout Germany, Schmeling is even said to have secretly provided refuge to two Jewish boys, Werner and Henri Lewin—sons of an acquaintance—in his apartment in the Excelsior Hotel in Berlin. “Max Schmeling risked everything he had for us,” Henri told the Los Angeles Times in 1989. He told me that what he’d done for me and my brother Werner in 1938 was ‘doing the duty of a man.’”

down and out

BOTH SCHMELING AND LOUIS, whose rivalry had foreshadowed the supreme contest of World War II, would go on to do their duty in uniform, serving their countries. After Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Schmeling had to undergo a physical examination for the Wehrmacht. Despite his boxing injuries and being nearly 34, beyond draft age, he was called up. He felt as if he was being singled out for punishment. It was rumored that Goebbels and Hitler hoped Schmeling would “die a hero’s death,” thus atoning for his defeat to Louis. Schmeling later maintained that his induction had been arranged with “Hitler’s support and approval.”

In summer 1940, Schmeling was ordered to join a Luftwaffe Fallschirmjaeger parachute unit. He still didn’t believe he would see action—he was too well-known, too valuable surely, to waste in battle. He was wrong. On May 20, 1941, he boarded a Junkers Ju-52 bound for Crete. It was just after dawn the next day when he lined up with soldiers far younger, heard the sound of antiaircraft fire, and then jumped at about 500 feet above the ground: “I could see how some parachutes didn’t open and bodies smashed to the ground; other chutes were torn to shreds by machine gun fire,” he recalled. Schmeling landed badly in a vineyard, aggravating the injury to his vertebra that Louis had inflicted in 1938. He came under heavy fire before blacking out and was eventually taken to a German hospital in Athens to recover. He had spent just two days at the front.

On May 30, the Times of London reported: “SCHMELING KILLED IN CRETE.” They ran a correction the next day. Reporters in the U.S. made sure to inform Joe Louis that his old rival had in fact survived. “Smellin’ said some bad things about me and my people,” claimed Louis, but then added: “I’m glad he’s not dead.”

Louis spoke to the press again as the United States plunged into the abyss after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941: “I was mad, I was furious, you name it. Hell, this is my country. Don’t come around sneaking up and attacking it. If a fighter had done that to me, I would have smashed him. I’m strictly for fair deals and open fighting.”

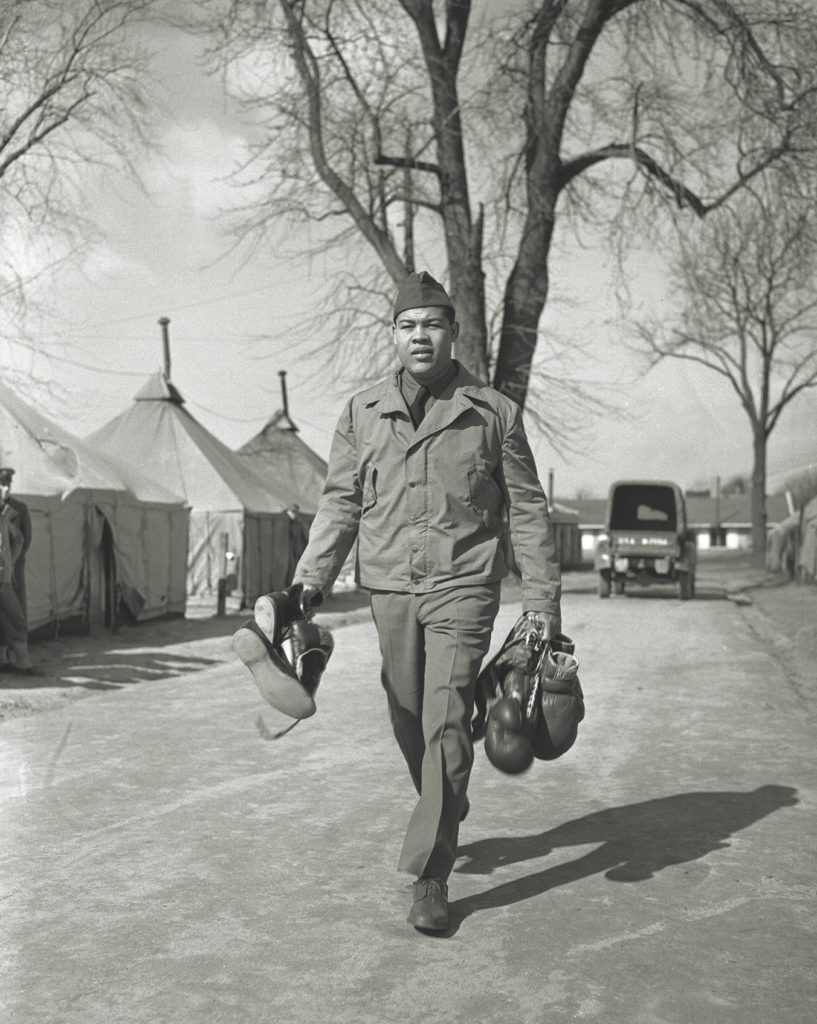

On January 10, 1942, Louis enlisted in the U.S. Army. “Joe has a date for a return engagement with Max Schmeling,” trumpeted the Chicago Tribune. Louis was soon busy raising morale across the United States, appearing in exhibition bouts and even risking his world title to raise funds for the war effort. “There’s a lot wrong with our country,” he said, “but nothin’ Hitler could fix.” In March 1942, he declared in New York: “I have only done what any red-blooded American would do. We gonna do our part, and we’ll win, because we’re on God’s side.”

“On God’s side” were words to inspire, and they were soon emblazoned on propaganda posters. President Roosevelt sent an appreciative telegram. “An aroused American,” Liberty magazine proclaimed, “like an aroused Joe Louis, can be a fearful thing to a hated enemy. A lot of other Max Schmelings in Berlin—and their yellow counterparts in Tokyo—are learning what one Max Schmeling learned in a New York ring.”

Corporal Joe Louis was on God’s side—but he was not blind to his own country’s failings and did not remain silent, protesting the ill treatment of his fellow Black soldiers, especially in the South. In one encounter in 1942 in Alabama, Louis was with future world middleweight champion Sugar Ray Robinson when an MP told him to leave a “Whites Only” waiting area: “Soldier, your color belongs in the other bus station.”

“What’s my color got to do with it?” an angry Louis asked. “I’m wearing a uniform the same as you.”

“Down here, you do as you’re told.”

The MP was about to club Louis when Robinson intervened, pulling the MP to the ground. Other MPs approached but then one called out: “Hey, that’s Joe Louis.”

Louis and Robinson were hauled away to face justice but Louis, protesting that he had been threatened, asked a provost marshal if he could “call Washington,” and the incident was smoothed over. “If I was just an average Black G.I.,” Louis recalled, “I would have wound up in the stockades.”

In March 1943, the month after the German defeat at Stalingrad, Schmeling was discharged from the Wehrmacht with the lowly rank of corporal. Even so, there were reports that he had been lost in combat—with some G.I.s even searching for his grave. An American officer in command of a Graves Registration unit complained: “We are thinking of putting up a sign at the [cemetery] gate saying, ‘Max Schmeling positively isn’t buried here.’”

As German defeat became ever more likely, Schmeling appeared before troops to raise morale, receiving ecstatic applause. But he also worked with the Red Cross, “with permission from the Wehrmacht,” he said, “helping with prisoners of war. I was to visit Stalags from time to time and talk to prisoners, find out how they were doing, and add a little diversion to the monotonous life of the POW.” Schmeling added that his role was “a kind of gesture by the Wehrmacht to try to demonstrate humane treatment of the enemy in a war that was going increasingly badly.”

Sometimes accompanied by senior Wehrmacht officers, Schmeling was said to have tried to improve conditions in some camps. He himself maintained that he’d intervened with authorities to spare the life of an American colonel, P-51 pilot Henry R. Spicer, who had been sentenced to death for “attempting an armed escape.” Some prisoners asked for his autograph; others shunned him, urinating on photographs that “Hitler’s Heavyweight” had handed out. On one occasion, when a Black POW approached the boxer, another prisoner cried out: “Here comes Joe!” Schmeling couldn’t help but laugh out loud.

In April 1945, the Red Army fought relentlessly toward the heart of Berlin. Schmeling managed to escape before the Soviets encircled the city and made his way to Hamburg in the last days of the war. Much of the city, including his own house, lay in ruins, a frequent target of Allied bombers since 1939.

Schmeling did his best to rise from the ashes of Nazi Germany, like millions of his countrymen, and tried to set up a publishing company in Hamburg in the summer of 1945. His first publication would be Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, which the Nazis had ludicrously banned. But the venture failed when the occupying British Military Government refused to issue a publishing license: Schmeling was regarded as a tarnished figure, a tool of the Nazis. He needed a home but, while working on enlarging a small house, was arrested for failing to get planning permission and jailed for three months.

Joe Louis was discharged in October 1945. He had appeared before some five million servicemen and had given 96 exhibition bouts, traveling more than 70,000 miles in service to his country, for which he was awarded the Legion of Merit medal. He appeared in nine more exhibition bouts in as many weeks at the end of 1945, and retained his world title in two fights in 1946.

Schmeling, meanwhile, was at an all-time low, depressed and living “hand to mouth.” To obtain a boxing license so he, too, could return to the ring, he had to go through a formal process and answer a “denazification questionnaire.” Finally, a British military tribunal cleared him in 1947 of being a Nazi and he was given what was known as a “Persilschein”—a “Persil certificate,” named after a laundry detergent. And so Schmeling put on his gloves once more and in September 1947 won his first fight since 1939. He was victorious again that December. But he could no longer defy age and his old injuries. In October 1948, aged 43, he lost a brutal 10-round fight and decided to retire.

Joe Louis retired three years later at age 37 after losing to Rocky Marciano in 1951. In 69 professional fights, he had lost just three times.

Schmeling went on to find work with Coca-Cola, eventually running his own bottling plant and amassing a considerable fortune in the German economy’s postwar boom. When he died in February 2005 at age 99, he was celebrated as Germany’s best-loved boxer.

Fate was not so kind to Joe Louis. His last decades were darkened by demeaning comebacks, a broken marriage, booze, drugs, and mental illness. Louis had somehow blown the millions of dollars he had made since turning professional in 1934 (his generosity was legendary in Harlem), and had failed to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxes. Had Las Vegas high-rollers not stepped in, finding him a $50,000-a-year job in 1971 greeting guests at Caesar’s Palace, Louis might have spent his last decade standing in welfare queues before his death in 1981.

in each others’ corner

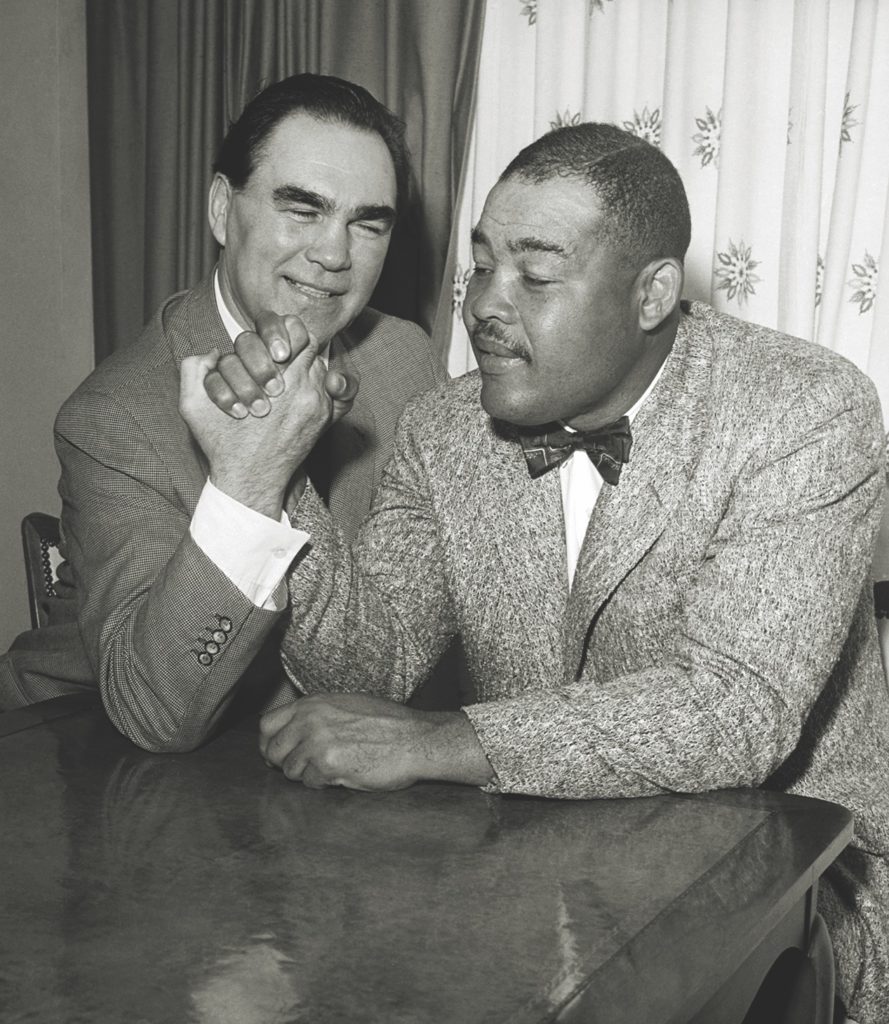

ONE OF JOE LOUIS’S COMFORTS in his last years was his friendship with Max Schmeling. In 1954, haunted by memories of the animosity the press had whipped up in 1938, Schmeling tracked Louis down to Chicago. Louis was stunned to see Schmeling, but after a few seconds he exclaimed: “Max! How good to see you again.” Schmeling vividly recalled how embracing Louis for the first time outside a boxing ring meant far more to him than would a third bout against the fighter even Muhammad Ali had once called “the greatest.”

The two boxers reminisced over coffee. There were no hard feelings—far from it. Schmeling realized just how much “the hatreds of the times” had conspired to separate them. “From that day, our friendship really started,” remembered Schmeling. “We had never really been enemies.”