That Jo Mora became an artist wasn’t a surprise. Mora’s father was a sculptor, and his brother a painter. But few could have predicted Jo would become known for paintings, sculpture and musings centered on the American West.

Joseph Jacinto “Jo” Mora was born in Uruguay on Oct. 22, 1876, and moved with his family to the Eastern United States a year later. After studying art in New York and Boston, he got his first commission in 1895, to paint a mural in a Brooklyn skating rink, and two years later landed a job at The Boston Traveler newspaper as an illustrator and cartoonist.

That wasn’t exactly Charles M. Russell’s path to creating a Western art legacy.

So what led Mora to work as a cowboy and live with the Hopis while learning about and rendering art that portrays Indian culture? What prompted him to write and illustrate books about American cowboys and early California vaqueros and spend his last 27 years in northern California?

“I think it starts with his dad,” says Peter Hiller, author of the 2021 biography The Life and Times of Jo Mora: Iconic Artist of the American West. “His dad was also a cattleman and moved to Uruguay before Jo was born.…His dad would tell him stories, and his memories were based on stories his dad told him.”

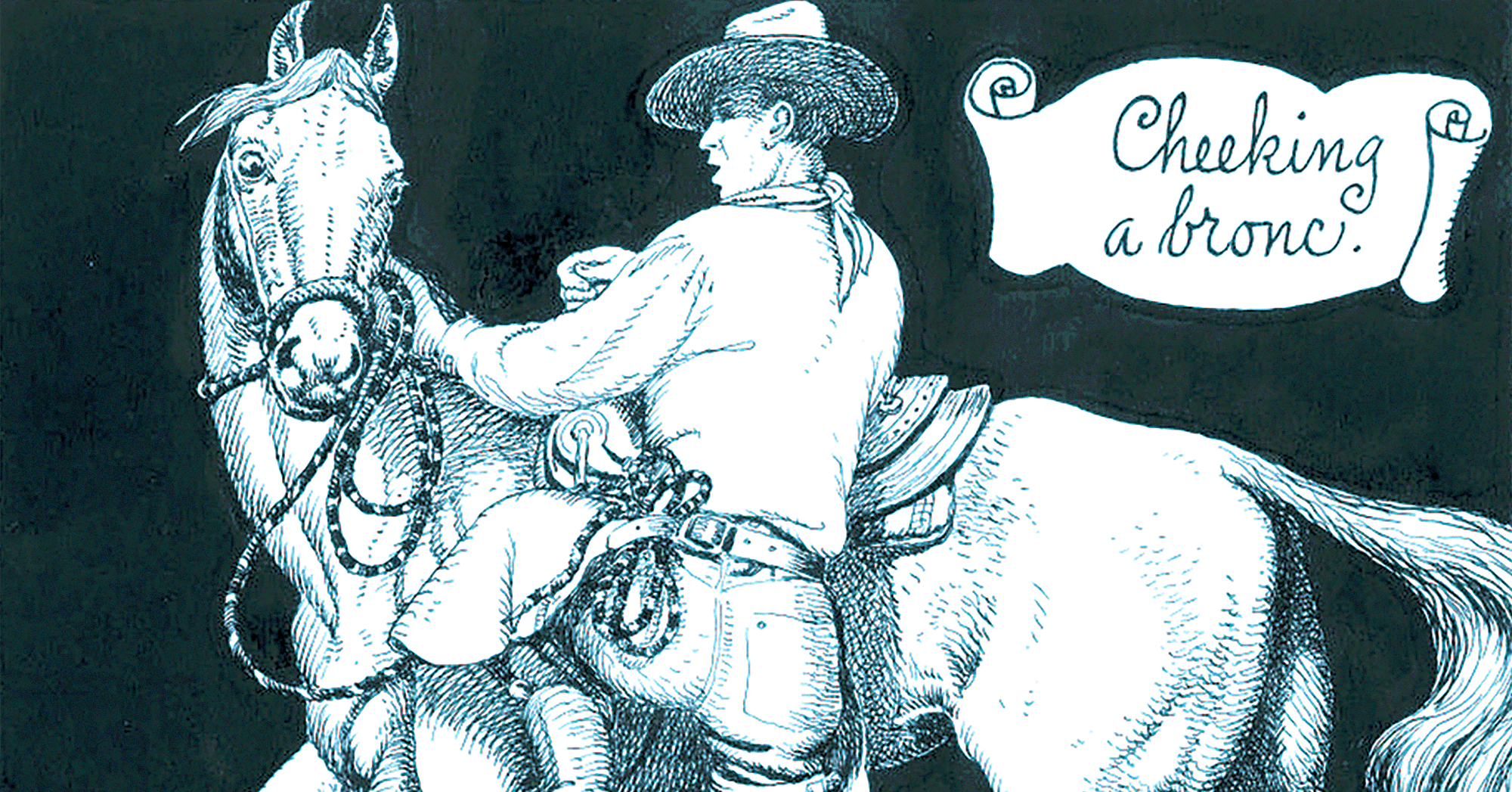

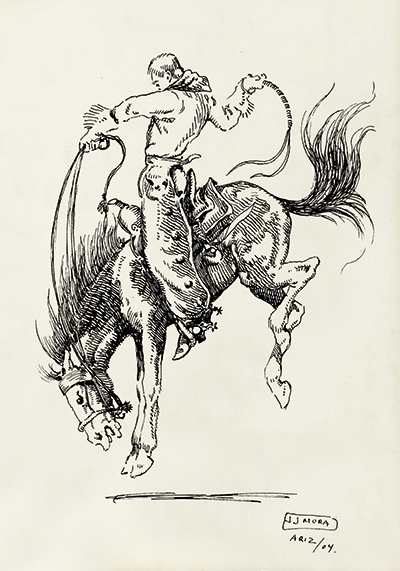

When Mora was in his mid-20s he headed west, first to California. “And he did exactly what he intended to do,” Hiller says. That included cowboying on Western ranches and working with California vaqueros. When Frederic Remington first saw the young artist’s work, he offered encouragement. “Son, you’re doing fine,” Mora recalled the artist telling him. “Just stay with it.”

Mora did. At one ranch he turned an abandoned shack into his studio—“after dispossessing the tarantulas and scorpions,” the artist recalled—and worked on clay sculptures whenever he had free time. Meanwhile, he became a good rider and cowhand.

“For him it wasn’t book learning,” Hiller says. “It was actually doing it.”

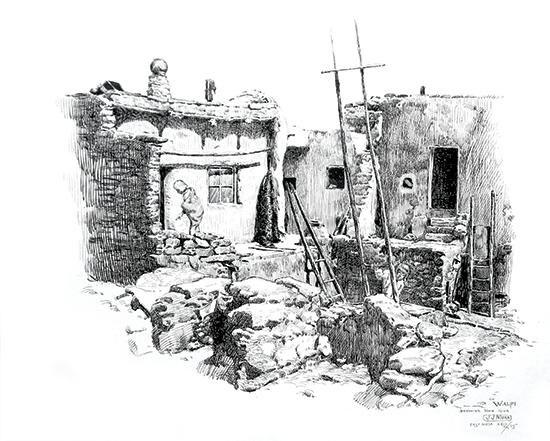

In 1904 Mora moved to northern Arizona, where he forged a lasting relationship with Hopis and Navajos. He learned the languages of both and lived with the Hopis for almost three years.

“[Mora] wrote to his parents, ‘If I don’t leave now, I’m gonna spend the rest of my life here,’” Hiller says. “He was included in ceremonies. He wasn’t there as a tourist, passing through. He was there to adsorb them and be a humble guest and learn as much as he could about the cultures, which he did. He wasn’t the only one who spent time there in the early 1900s, but he might have been the single person who so graciously let them embrace him instead of him imposing himself on them. I think some of the other artists and photographers took but didn’t give back. Jo certainly gave back.”

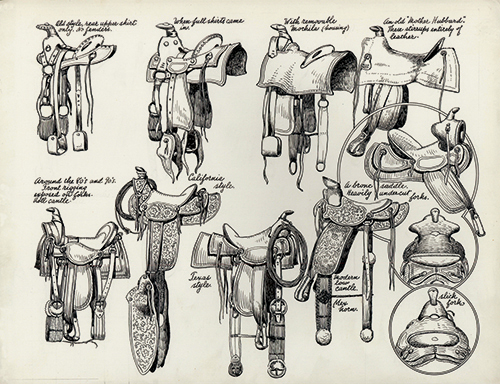

Mora also worked as a printmaker, pictorial cartographer, architect and photographer. As a writer he’s best known for Trail Dust and Saddle Leather (1946) and Californios: The Saga of the Hard-Riding Vaqueros, America’s First Cowboys (1949), which was published posthumously. Mora died in Monterey, Calif., on Oct. 10, 1947. Among other books to revisit his work was the 1979 retrospective The Year of the Hopi: Paintings and Photography by Joseph Mora, 1904–1906, published by the Smithsonian Institution.

Ironically, Mora’s broad range of subject matter may have hurt him. “Not many artists work in the variety of mediums he worked in, and that’s probably an asset for him,” Hiller says. “But it was also maybe why he’s not as well known, because he didn’t have the singular focus of a Remington or a Russell, who painted and sculpted, and that was about it.”

But Mora left a legacy, nonetheless: “A celebration of the American West and Native American cultures,” Hiller says. For more information visit the Jo Mora Trust. WW