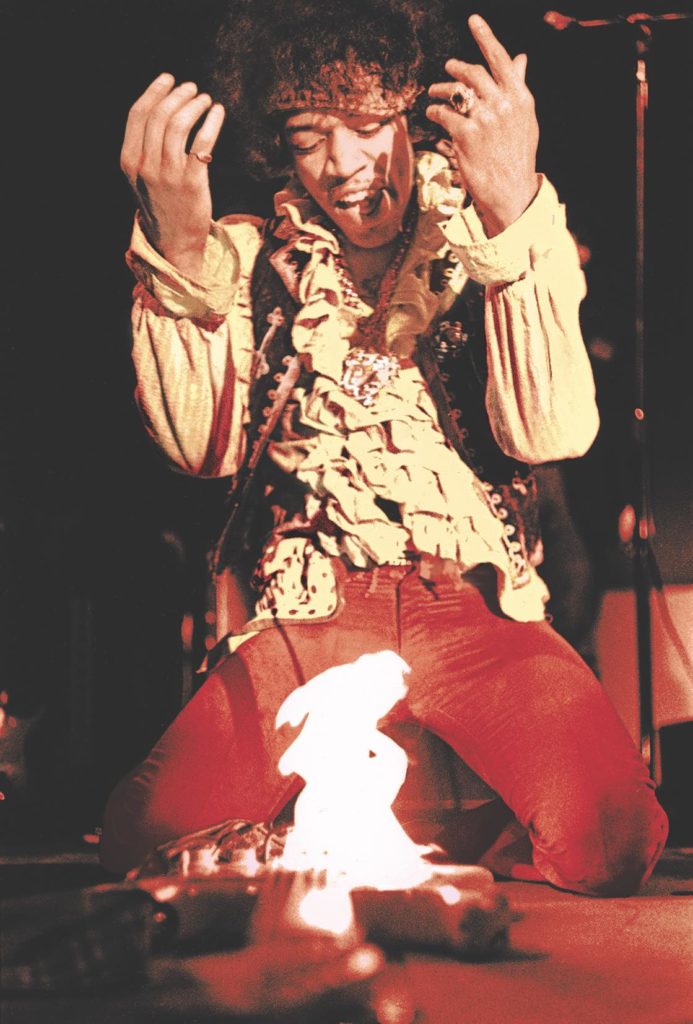

No matter where you served in Vietnam in the 1960s, the slashing rock ’n’ roll guitar of James “Jimi” Hendrix was heard on radios, record players and eight-track tape decks. Electric Ladyland, the critically acclaimed album released by Hendrix in 1968, sold millions of copies and showcased Hendrix’s incredible talents.

More than a few GIs soon came to think that “All Along the Watchtower” was really Hendrix’s tune—and not a cover of a song by Bob Dylan. “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary” also were played over and over. Rolling Stone magazine considers Hendrix to be the greatest guitar player of all time.

But many who served in Vietnam and admire Hendrix’s skill with a guitar do not know that he was a paratrooper in the 101st Airborne Division. They also do not know that Hendrix figured out how to cut short his three-year enlistment to launch his career as a musician by exploiting prejudices against homosexuality.

Trouble with the law

Hendrix, born in Seattle the day after Thanksgiving 1942, grew up poor and dropped out of high school. Some of his African American male friends, who like him had few job opportunities, joined the armed forces. Hendrix also considered enlisting, especially after he was arrested by the local police for riding in a stolen car.

After being arrested again just four days later for riding in another stolen car, Hendrix knew he would be prosecuted this time and could go to jail for 10 years. Yet he also knew that prosecutors in Seattle often were willing to make a deal—a plea bargain—with a young male defendant if he would leave town and join the Army. Hendrix went to an Army recruiter in Seattle and asked if it was possible to join the 101st Airborne Division. He had read about the “Screaming Eagles,” as the division’s soldiers were called, and wanted to be a paratrooper.

On May 16, 1961, a public defender representing Hendrix struck a plea bargain with the local district attorney. Hendrix received a two-year suspended prison sentence on the condition that he enlist in the Army. The following day, he enlisted for three years as a supply clerk and shipped out to Fort Ord, California, for basic training.

At first, the young private liked military life. After two months at Fort Ord, he received orders for Fort Campbell, Kentucky. He arrived there on Nov. 8, 1961, and immediately began airborne training. “Here I am,” he wrote to his father, “exactly where I wanted to go. I’m in the 101st Airborne . . . [it’s] pretty rough, but I can’t complain, and I don’t regret it . . . so far.”

Becoming a Screaming Eagle

Hendrix made his first jump out of an airplane that winter. “The first jump was really outta sight,” he later told a friend. Like many paratroopers, Hendrix feared that his parachute might fail. He overcame it, made five jumps and earned his parachutist badge, along with the extra $55 a month that came with being on jump status. Hendrix was promoted to private first class in January 1962 and completed the requirements to wear the Screaming Eagle patch. He was so proud of that patch that he bought extra ones to send to his family.

Only a few months later, however, Hendrix decided that he liked the Army—and soldiering—less and less. The military was interfering with his true love: rock ’n’ roll music. Hendrix had his guitar with him and recruited friends for a band that got weekend gigs in Nashville and at military bases as far away as Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Hendrix knew that he could not simply quit the Army, and if he went AWOL he might be court-martialed and sent to prison. In April 1962, having finished just 10 months of his 36-month enlistment, Hendrix spoke to an Army psychiatrist at Fort Campbell and told him that “he had developed homosexual tendencies and had begun fantasizing about his [male] bunkmates.” On a subsequent visit, Hendrix told the doctor that he was “in love” with a male member of his squad.

Those were fabricated claims about his sexuality that Hendrix knew could get him out of uniform. Under Army regulations then in force, a gay soldier was subject to separation because his presence in the Army was thought to impair morale and discipline.

Being Gay Meant Being ‘Unfit’

According to the regulation, this “unfitness to serve” was attributed to the Army’s then-reasoning that “homosexuality is a manifestation of a severe personality defect which appreciably limits the ability of such individuals to function effectively in society.”

In practice, that meant a soldier who demonstrated “by behavior a preference for sexual activity with persons of the same sex” could be discharged with a general or an undesirable discharge—although an honorable discharge might be given in exceptional cases. Hendrix was sufficiently familiar with the regulation. He knew what he needed to say.

In May 1962, Capt. John Halbert, a doctor, gave Hendrix a comprehensive medical examination. Halbert concluded that Hendrix suffered from “homosexuality” and recommended he be discharged because of his “homosexual tendencies.” He was discharged for “unsuitability” on July 2, 1962.

Hendrix must have received at least a general discharge under honorable conditions, as his final paycheck included “a bonus for twenty-one days of unused leave.” Had he received a discharge under “Other Than Honorable” conditions, there would have been no bonus.

After his discharge, Hendrix embarked on a red-hot career as a musician. He never admitted how he had used his knowledge of Army regulations to obtain an “early-out” and return to civilian life. Instead, he told his friends that he had broken his ankle on his 26th jump and was discharged for that physical disability. However, his Army record contains no evidence that Hendrix was discharged due to an injury.

Dying a rock star at 27

Had he lived longer, Hendrix likely would have been surprised at the changing attitudes about the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community in America—and in the U.S. Army. Unfortunately for Hendrix, his “reckless mixing of drugs and alcohol,” as Charles R. Cross described it in his 2005 biography Room Full of Mirrors, resulted in his death in London on Sept. 18, 1970. He was 27 years old.

Hendrix is not the only musician or celebrity from that era who served in the armed forces. Johnny Cash served in the Air Force from 1950 to 1954, and Elvis Presley was in the Army from 1958 to 1960. Only Jimi Hendrix had the distinction of being a paratrooper, and it seems his knowledge of law and regulations got him back into civilian life earlier than might have otherwise been expected.

Fred L. Borch is a retired judge advocate colonel who serves as the regimental historian for the Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps. He is the president of the Orders and Medals Society of America and the author of several books on American military decorations.

This article appeared in the June 2022 issue of Vietnam magazine.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.