American volunteers took up arms again in the 1948 War of Independence

IN 1945, amid revelations about Hitler’s Final Solution for Europe’s Jews, many Holocaust survivors emigrated to the United States. Others, convinced of the need for a Jewish homeland, clamored to go to Palestine. That region, bounded by Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, and Trans-Jordan, comprised most of the biblical Holy Land. The Muslim conquest of Palestine in the 7th century had left the population largely Arab. In the 1880s, however, Jews from across Europe, weary of persecution and embracing Zionism, a movement espousing the restoration of a Jewish nation, began settling in Palestine.

Over millennia, many nations had controlled Palestine. Since the 1920s, under a mandate from the League of Nations, Britain had been administering the region, trying to maintain peace between Arab and Jew.

In 1948 Jews in Palestine declared a land of Israel there. War broke out as adjoining Arab states arrayed their armies against the new state. The fledgling Israel Defense Forces, which came to total nearly 118,000 troops, included some 1,250 Americans, mostly World War II veterans.

Under League of Nations Mandate governance, Palestine had been a cultural and political powder keg, with British authorities constantly snuffing fuses lit by Arabs, the region’s majority, and Zionist militias—the Lehi, or Stern Gang, the Irgun, and the Haganah. The first two were rough-and-tumble guerrilla fighters, the last a more mainstream creation of the Jewish Agency, the unofficial government of Jewish Palestine. In 1939, seeking to cosset its Arab allies in the Middle East, Britain set quotas on Jewish immigration. Jewish activists countered by sending toward the region shiploads of European refugees—a Haganah operation, known as Aliyah Bet, or “plan B”, that recruited American volunteers. World War II interrupted that flow, which resumed in 1945, with the Royal Navy intercepting most Aliyah Bet vessels before they could land. In Palestine, the Stern Gang, the Irgun, and the Haganah were conducting irregular operations against British forces and Arab opponents.

By 1947-48, Zionism was enjoying increasing support in the United States. The first North American volunteers to put themselves on the line numbered about 240. These Americans and Canadians helped man Aliyah Bet ships, many of them acquired in the United States by F & B Shipping, a Haganah front whose initials stood for “F___ Britain.”

One of these seamen was Paul Kaye, a Jewish U.S. Navy veteran who was living in New York when he answered his phone to hear a voice he did not recognize. “We would like to know if you would like to help your people,” the caller said. “Be on the corner of 39th Street and Lexington Avenue on Thursday at 4 p.m. You’ll see a man with a black leather jacket. If he puts a newspaper under his arm, follow him. If he throws it out, walk away—you’re being followed.” Kaye followed instructions, watching his contact until the man put a newspaper under his arm. Following the fellow into a building, Kaye found himself face to face with a third man. “We would like you to run small ships between Cyprus and Palestine,” the recruiter explained. “If the British catch you, they’ll hang you.” “Let’s go!” answered Kaye. Kaye’s first berth was Hatikvah—Hebrew for “Hope”—which sailed from Baltimore, Maryland, to board 1,500 Holocaust survivors at Marseilles, France, then make a run at the British blockade. The Royal Navy prevailed. Mandate authorities detained the Hatikvah passengers at a camp near Haifa. Kaye escaped to France, where he worked with the Jewish underground.

In 1947, the United Nations voted to partition Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state. Arab and Jewish irregulars responded with bombings, sabotage, and ambushes. Arab volunteers from neighboring countries began to enter Palestine and organized into the Arab Liberation Army. In the United States, President Harry S. Truman sympathized with the Jewish cause. However, many high-ranking State Department officials feared recognition of a Jewish state would cause Arab oil-producing nations to restrict oil supplies to the United States and trigger instability, perhaps boosting the Soviet role in the region. “There are 30 million Arabs on one side and about 600,000 Jews on the other,” said Defense Secretary James Forrestal.

In December, the United States embargoed sale of American arms to anyone from Palestine. To maintain a clandestine flow of weapons and materiél to its personnel in Palestine, the Haganah sent emissaries to the United

States. Si Spiegelman, born in Belgium and brought to New York as a child refugee, belonged to a religious Zionist youth group. He recalls how, with a friend, he collected military weapons brought home as souvenirs by ex-GIs sympathetic to the cause and shipped them to contacts in Palestine labeled “machinery.” In Los Angeles, California, Elihu King, another former Zionist youth group member, wrote in a memoir about degreasing army surplus machine guns for use by Jewish forces in Palestine. American supporters of the Haganah came from all over, including the underworld. Jewish mobster and Las Vegas kingpin Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, introduced to a Haganah fundraiser, asked, “Jews are fighting?”

Yes, the Haganah man said.

“Fighting, as in killing?”

Yes.

Satisfied, Siegel supplied cash by the suitcase full.

To recruit fighters, Haganah emissaries set up the group Land and Labor for Palestine. Officially, Land and Labor was placing American volunteers in industrial and agricultural jobs in Palestine to free resident Jews for military duty; in reality, when Yanks arrived, they went into the IDF. As had been so in the 1930s during the Spanish Civil War, Americans joining this fight were violating a federal ban on citizens participating in combat on behalf of a foreign power. The U.S. State Department warned that those who did could lose their citizenship, although this rarely happened.

Encounters between American Jews and Jews born in Palestine could be tense. The latter, who called themselves sabras after a species of desert cactus, stereotyped diasporic Jews in general as timid and complacent and American Jews in particular as whiners. Sabras resented Americans’ intense ties to their homeland, insisting volunteers set aside national identity and regard themselves foremost as Jews.

Land and Labor opened its first branch in New York City at the Breslin Hotel. Soon L&L had operations going in all major American cities with large Jewish populations, according to David J. Bercuson in his 1984 book The Secret Army. Recruiters often worked through Jewish veterans’ organizations, sometimes obtaining lists of Americans who had served during the war and telephoning those with Jewish-sounding names. Merely phoning was risking surveillance and arrest; in 1947-48, American passports bore the message, “This passport is not valid for travel to or in any foreign state for the purpose of entering or serving in the armed forces of such a state.”

American volunteers for the war in Palestine sometimes belonged to Zionist youth groups. These ranged from the socialist Hashomer Hatzair, or Young Guard, which espoused a binational Jewish-Arab state, to the right-wing Betar, advocate of a Jewish state “on both banks of the Jordan.” Others, raised in assimilated families, had had little connection to Jewishness until the war. Women volunteered, usually as nurses. A handful of non-Jews volunteered as well.

Not all American volunteers came through Land and Labor—they joined the Haganah in Europe and in Palestine itself. In 1947, Zipporah Porath, an American, was studying at Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

At a student hangout someone passed Porath a note asking her to set up an appointment with a stranger. At their first meeting, the man asked, “Are you ready to defend Jerusalem?” Eventually, in a high school basement, Porath underwent interrogation and, taking a Bible in one hand and a pistol in the other, recited the Haganah oath of allegiance.

Most recruits passed through the Land and Labor suites at the Hotel Breslin for a brief interview and perfunctory medical exam. Spiegelman recalls that just before he embarked for Palestine, he and other recruits underwent indoctrination at a farm near Peekskill, up the Hudson River from New York City. “The reason they held it there was so nobody would talk—there were no telephones,” Spiegelman says. “If they held it in New York City, somebody would have said something.” When interacting with the authorities or anyone suspected of snitching, volunteers soft-pedaled information about their destination and reasons for travel. Spiegelman—whose parents had lived in Poland before they moved to Belgium, where he was born, eventually escaping Europe and coming to New York—had obtained a Polish passport that circulated among shipmates. To avoid snags over their country’s ban on serving in a foreign military, as American volunteers boarded ship they surreptitiously passed the Polish identity card hand to hand, each in turning presenting it.

Typically, volunteers reached Palestine through Marseilles, France. Early arrivals sailed to Haifa aboard Marine Carp, a former Liberty ship. Elihu King remembered the accommodations as “frugal”—women slept six to a cabin; men, in huge compartments full of bunks. Marine Carp was en route in May 1948 when Israel declared statehood and surrounding Arab countries, along with Saudi Arabia, declared war. When Carp docked at Beirut, Lebanon, Lebanese troops imprisoned the ship’s Jewish male passengers.

At Haifa, Spiegelman and companions underwent a few days of “sketchy” military training. Trainers issued them uniforms or parts of uniform and offered rudimentary instruction in Hebrew, Israel’s official language. The

Haganah was now the Israel Defense Forces. Some IDF units were heavy with English speakers—mainly Americans, Canadians, and South Africans. “If you wanted an English-speaking unit,” said Spiegelman, “you went to the 72nd or 79th Battalion.” In Machal: Overseas Volunteers in the Israel’s War of Independence, author Yaacov Markovitzky reports that in summer 1948 the 7th Armored Brigade had 170 English-speaking volunteers, a tally that by October was nearing 300. Canadian WWII veteran Ben Dunkelman commanded the brigade, which as soon as Israel declared statehood saw plenty of action, since five Arab armies had invaded the new state from many points on the compass. When Operation Dekel—“Palm Tree”—in July resulted in the capture of Nazareth from the Arab Liberation Army, Dunkelman refused to obey orders to expel Nazareth’s Arab residents. In October’s Operation Hiram, the 7th and other brigades captured the Upper Galilee from the Arab Liberation Army and a Syrian battalion. In the aftermath of Hiram, allegations arose of atrocities against Arab civilians, especially at Safsaf, where more than 50 villagers died; IDF inquiry results remain classified.

Americans could be found almost everywhere in the IDF (See “Wings Over the Desert,” and “Brothers in Arms,” below). Spiegelman joined a unit that fought in the Bet She’an, an area in northeast Israel. After serving aboard two clandestine refugee ships, Paul Kaye joined an underwater demolition team in the fledgling Israeli navy. During the siege of Jerusalem during the first half of 1948, residents of Jewish west Jerusalem, cut off from the rest of the country by Arab forces, lived on canned sardines, powdered milk, and crackers. Zipporah Porath was a nurse and medic in besieged Jerusalem. Elihu King, after rotating through several units, ended up in the Negev Brigade, named for the desert where it fought the Egyptian Army.

American volunteers encountered problems expected and unexpected—such as friction with the military establishment, going unpaid, fluid policy toward them and their role, and not knowing Hebrew. To integrate them, the IDF set up the Mahal—or Machal—division, named for a Hebrew acronym meaning “Overseas Volunteers” and dedicated to smoothing the way. Machal published newspapers and training materials in English, French, and other languages and opened a social center in Tel Aviv where volunteers could meet.

The best-known American volunteer may have been David “Mickey” Marcus. A West Point-educated New Yorker who served as a U.S. attorney in his hometown in the 1930s, Marcus, a colonel in the U.S. Army, was an advisor at the Allied conferences at Teheran, Yalta, and Potsdam. In late 1947, the Jewish Agency recruited him. Though he spoke little Hebrew, Marcus wrote training manuals for the Haganah and the IDF and in the Negev Desert formulated a small-unit doctrine that focused aggressive nighttime hit-and-run tactics against a well-equipped Egyptian army. Marcus helped break the Arab siege of Jerusalem by supervising construction of the “Burma Road,” a bypass around Arab positions that reconnected the city with the rest of the country. In May 1948, the IDF made Marcus a general. He located his headquarters in a former monastery near Jerusalem. Late on June 10, Marcus, draping himself in a white blanket against the evening chill, told the sentry on duty he was going for a stroll. The general was in uniform but wearing no insignia. While Marcus was out, the sentry he spoke to went off duty, replaced by an 18-year-old who only spoke Hebrew. Seeing a figure dressed like an Arab approach, the young soldier asked in Hebrew for the password. Marcus answered in English. The sentry fired a warning shot. Marcus ran for the monastery, prompting the sentry and other soldiers to fire, killing their commander. Marcus is buried in the cemetery at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York.

In March 1949, Israeli forces secured the southern Negev, ending the war, during which 119 overseas volunteers, 40 of them North Americans, had died. Surviving American volunteers mostly returned home—some satisfied at having helped birth Israel, others wincing at the culture clash they had encountered fighting on behalf of a Jewish state.

For years, Israel did little to recognize foreign volunteers who served in the War of Independence. The country’s leaders emphasized self-reliance, a stance at odds with accepting help from abroad. But in 1993, at Sha’ar Hagai, near the old Burma Road, Israeli officials dedicated a monument honoring the overseas volunteers killed in Israel’s struggle for survival. The story of 1948’s American volunteers is carried on by the American Veterans of Israel Legacy Foundation, whose ranks include a dwindling number of veterans and family members and which maintains a virtual museum at israelvets.com.

[hr]

Wings Over the Desert

In the Israeli fight for independence, American volunteers were key to the air war. Until late 1947, the Jewish state-in-the-making had few pilots and only a handful of small planes. Al Schwimmer, a Trans-World Airlines flight engineer, got into the act when Yehuda Arazi, a Jewish Agency representative, asked for help procuring aircraft. From his work, Schwimmer knew of surplus military planes stored on the West Coast available for sale to any American veteran. He left TWA and moved to California. With Arazi, Schwimmer and Florida-born Irv Schindler, who had ferried planes from the States to Europe during the war, set up Service Airways.

The company bought C-46 and C-47 transports and Lockheed Constellations. Schwimmer and compatriots shuttled the planes to New Jersey as the Haganah was setting up an air base in Italy from which to fly to Palestine.

In February 1948, Schindler and other volunteers began ferrying Service Airways planes to Europe—duty that included nightclubbing in Rome. In the 2014 documentary Above and Beyond, director Nancy Spielberg shows the American airmen in the air and on the town.

American authorities’ suspicions of a Haganah connection caused the route to the Middle East to meander through country upon country before planes touched down in Palestine. Eventually, the United States moved to impound the Service Airways fleet.

However, Schindler, using connections in Panama, formed a new airline, and kept flights going. Pilots also flew C-46s to Czechoslovakia, which had an arms deal with Israel. The Czechs had sold the Israelis 25 Avia S-199 fighters, a variant on the German Messerschmitt Bf-109, and, later on, a large quantity of British-made Supermarine Spitfires.

Former U.S. Marine aviator Lou Lenart described the S-199 as “the worst piece of crap I have ever flown,” jerry-rigged from wartime parts. Israeli mechanics disassembled the cobbled-together fighters, packed the components into C-46s, and flew them to Palestine to be reconstituted. The rebuilt planes saw action in May 1948. Egyptian forces were 30 miles from Tel Aviv, making their way north until Lenart led a flight of four S-199s on a bombing and strafing run that surprised the Egyptians, who had thought the Israelis had no air power.

The next day, American pilot Milton Rubenfeld, who like many of his dual-allegiance compatriots spoke no Hebrew, was flying in tandem with Israeli pilot Ezer Weizmann. When the two attacked an Iraqi column in north-central Israel, unfriendly fire disabled Rubenfeld’s S-199. He had to bail out over the Mediterranean.

In the water Rubenfeld extricated himself from his plane and began swimming toward shore. Armed kibbutzniks there, mistaking him for an Arab, opened fire. “Shabbos!” Rubenfeld shouted, exclaiming the Yiddish for Sabbath. “Gefilte fish!” Hearing familiar words, his attackers put down their rifles and rescued him. In time Rubenfeld returned stateside, where his son Paul changed the family name to Reubens, became a comic actor, and achieved fame as Pee-Wee Herman.

[hr]

Brothers in Arms

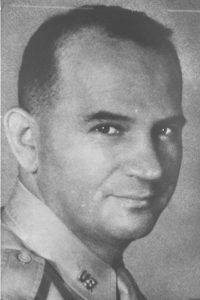

My father’s name was Harlow Geberer. He and his brother Milton were born in the Bronx, New York, in 1922 and 1920 to Benjamin and Minnie Geberer, who had emigrated to the United States from Romania. The boys had a sister, Beatrice. Milton, who in his teens joined a left-wing Zionist youth group, briefly attended college, but at a young age married and became a father. He studied Hebrew and Arabic. During World War II he served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Harlow also joined up, becoming a sergeant in the military police and participating in the Normandy invasion. After the war, Harlow became involved in a Zionist group, among whose members he met my mother. In 1947, traveling aboard the vessel Marine Carp, Milton and family moved to Jerusalem, where he worked in the Jewish Agency publications department. When the war for independence started, Milton joined the Haganah, which prized his language skills and promoted him to major. In May 1948, a reporter interviewed him. “The Arabs are good shots, but lousy fighters,” Milton said. “When we move in, they usually move out, but their snipers hurt us.” On May 17, near the Jerusalem railroad station, an Arab sniper shot him dead. Harlow volunteered in New York and also sailed for Palestine aboard Marine Carp. He was at sea when Israel declared independence and troops from five Arab states, including Lebanon, invaded the country. The Carp was to dock in Beirut, then sail to Haifa, Israel—but Lebanon was now at war with Israel. The ship’s captain radioed the U.S. consul in Beirut that he had many young Jewish men aboard and feared for their safety. The consul assured him there would be no trouble. At Beirut, officials took the ship’s Jewish male passengers into custody and detained them at Baalbek. The Carp then sailed for Haifa. Many suspected the State Department had tipped off the Lebanese. While my father and the rest were behind bars, he learned of his brother’s death. When Marine Carp returned to Beirut, authorities ordered the imprisoned volunteers to return home. Some disembarked at Palermo, Italy, and made their way to Israel to fight, but my dad returned to the States. In 1949, he and my mother went to Israel. They stayed a year, but my mother’s asthma landed them back in New York. —Raanan Geberer

This story was published in February 2019 in American History.