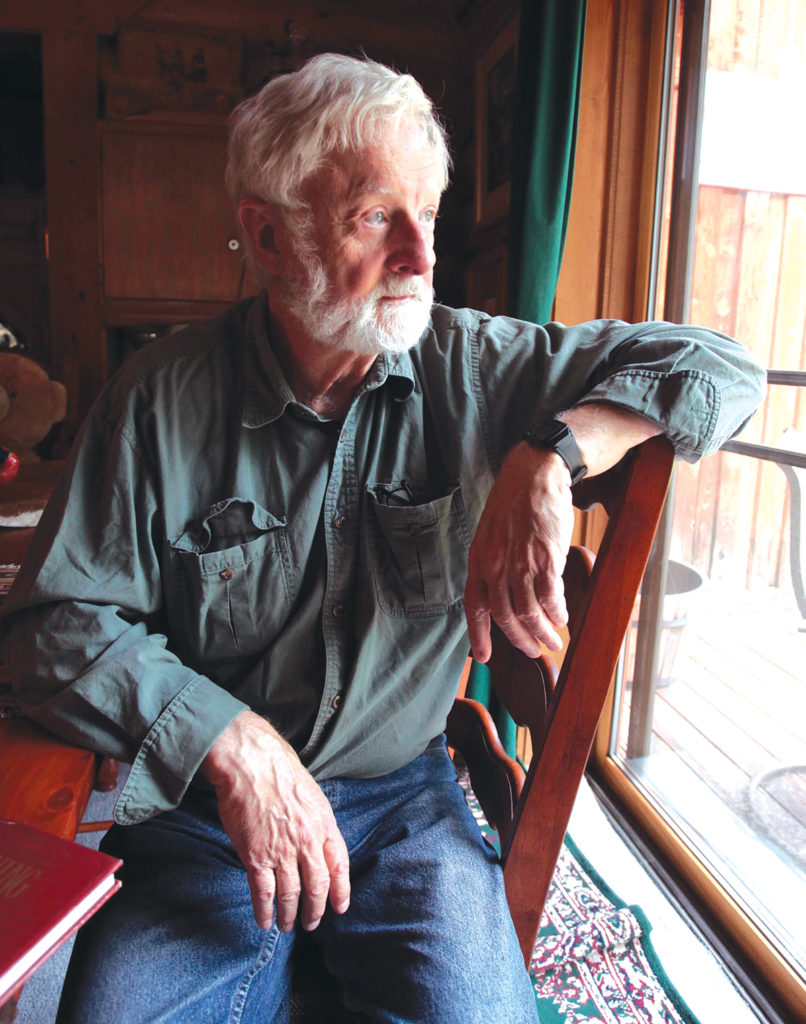

Artist Jerry C. Crandall, 87, died of COVID-19 on June 12, 2022, at home in western Montana, leaving behind widow Judy, two sons and a daughter from a previous marriage, as well as a cat (Billy the Kiddy) and a dog (Bridger James). He also leaves a 60-year legacy of historically accurate artwork, much of which deals with the American West.

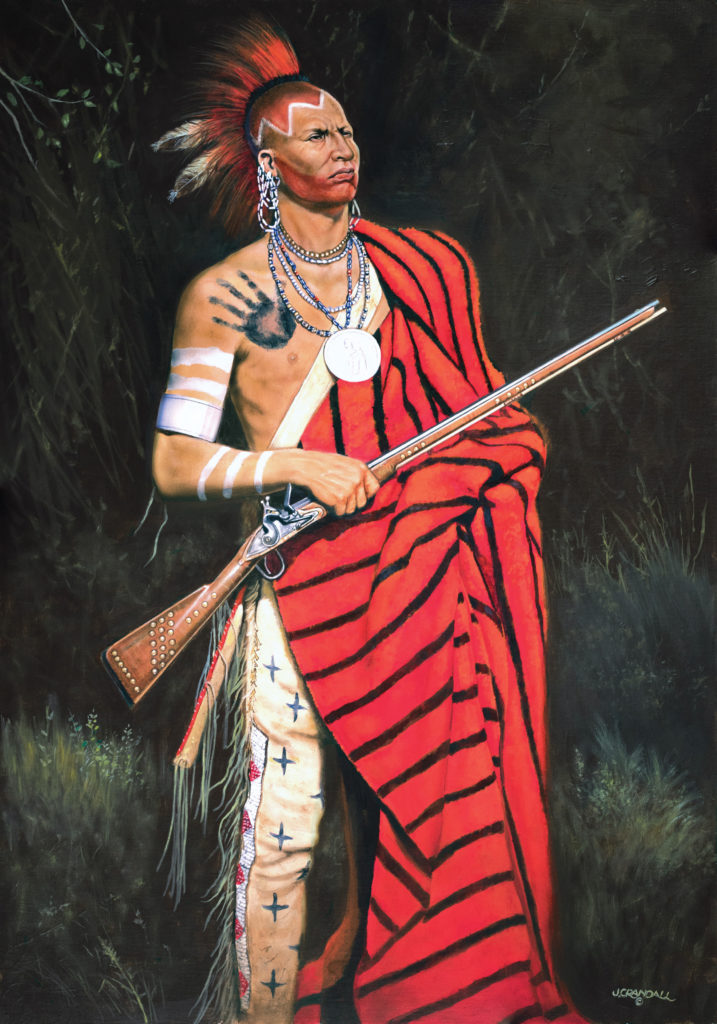

Judy Crandall recalls her husband’s attention to historical detail: “Jerry often said, ‘I want to accurately document a historical scene, to tell a story. It is OK for someone to criticize my art, but not my research.’” If the artist wanted to paint a charging cavalry soldier, for example, he first learned to ride in period gear like that trooper. In researching mountain men, he made and wore the clothes, fired the weapons, felt the cold. That painstaking approach also made him a natural as historical consultant for the TV miniseries Centennial (1978–79) and the big-screen films The Mountain Men (1980) and Tombstone (1993).

Crandall was born on April 1, 1935, in La Junta, Colo., near the site of Bent’s Fort on the Santa Fe Trail. His father loved history and art and encouraged Jerry to pursue both. Hired as an aviation artist by McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Co., in Long Beach, Calif., young Crandall worked on his own paintings in the evenings and on weekends. At one point a friend who brokered Western art took some of Jerry’s works to Fenn Galleries, in Santa Fe, and “came back with a very large check,” Judy says. “Sold them all.” Thus encouraged, in the summer of 1973 Crandall began painting full-time. His first show, with a fellow artist at Beverly Hills’ Petersen Galleries in April 1974, was a sellout. Jerry and Judy married on July 4, 1976, soon after the artist had rendered a portrait of Lt. Col. George Armstrong to mark the centennial of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. In 1982 the Crandalls moved to Sedona, Ariz., where Judy set to work promoting and advertising her husband’s work. In 1996 they moved to Montana.

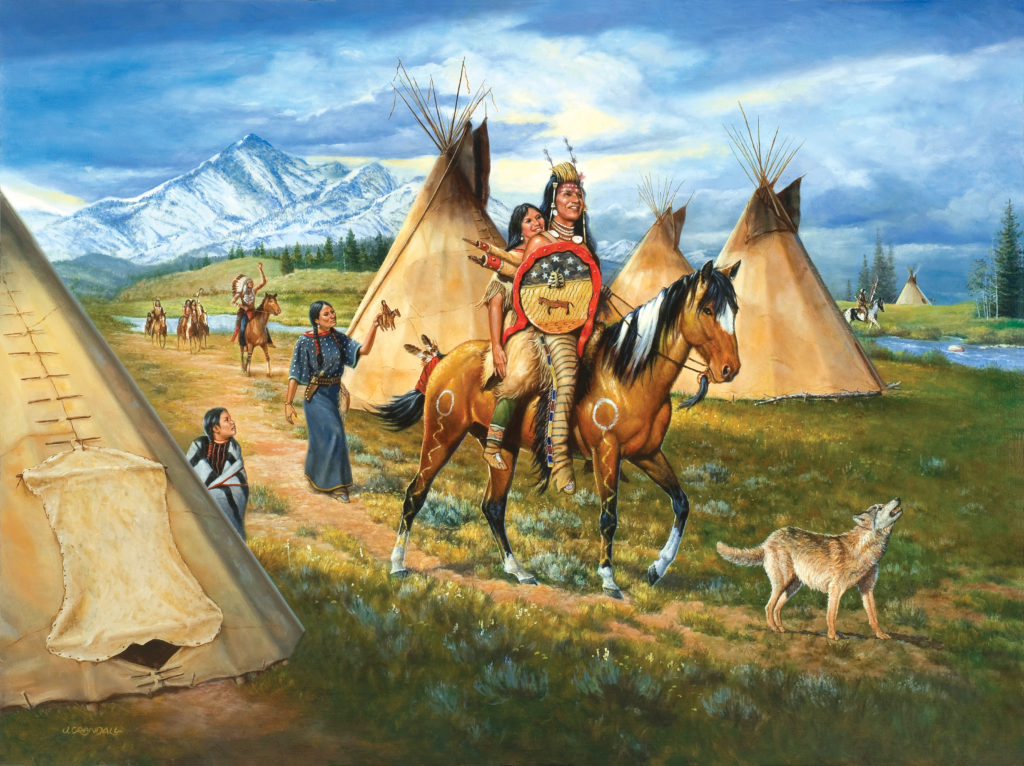

Crandall’s favorite subjects were American Indians and mountain men. “He loved their independent spirit, quest for exploration and colorful way of life,” Judy says. “These were tough people who Jerry wanted to correctly capture through historically correct paintings. Collectors eagerly sought out his work celebrating our unique Western history.”

Some of those paintings took months to complete. Others took years.

“An idea would jell after reading a journal, diary or other firsthand account of an event—and this process was complicated as well as time-consuming, as he wanted the painting to satisfy his objective,” Judy says. “Having the right model, re-creating the correct clothing and other necessary items were critical to the success of his work.

“He was always reading and researching something. He would make small sketches of images that grew in his mind based on his reading material. Once the painting was sketched out, he would paint every day until it was completed. He preferred to do one thing at a time, so once he decided on which project he wanted to tackle, he would go full force on it.”

Crandall also painted World War II scenes featuring pilots and planes of Germany’s Luftwaffe.

How does Judy think her husband would want to be remembered?

“That he was a student of history, the American West and World War II,” she says. “He wrote eight books on the Luftwaffe aircraft and men who flew these machines. Some have titled him an expert, and Jerry always corrected them, saying, ‘No, we are all students.’

“That he loved talking about his passionate love of history and always had time to talk to anyone and everyone who had questions.

“That he wanted to aid the movie industry by serving as a technical adviser, which he did for Centennial, The Mountain Men and some for Tombstone, in which he also did a stunt—falling off his horse on cue!” For such spunk Wild West salutes “Crash Crandall,” who threw himself soul, mind and, quite literally, body into his work.

For more on Jerry Crandall and his art visit eagle-editions.com.