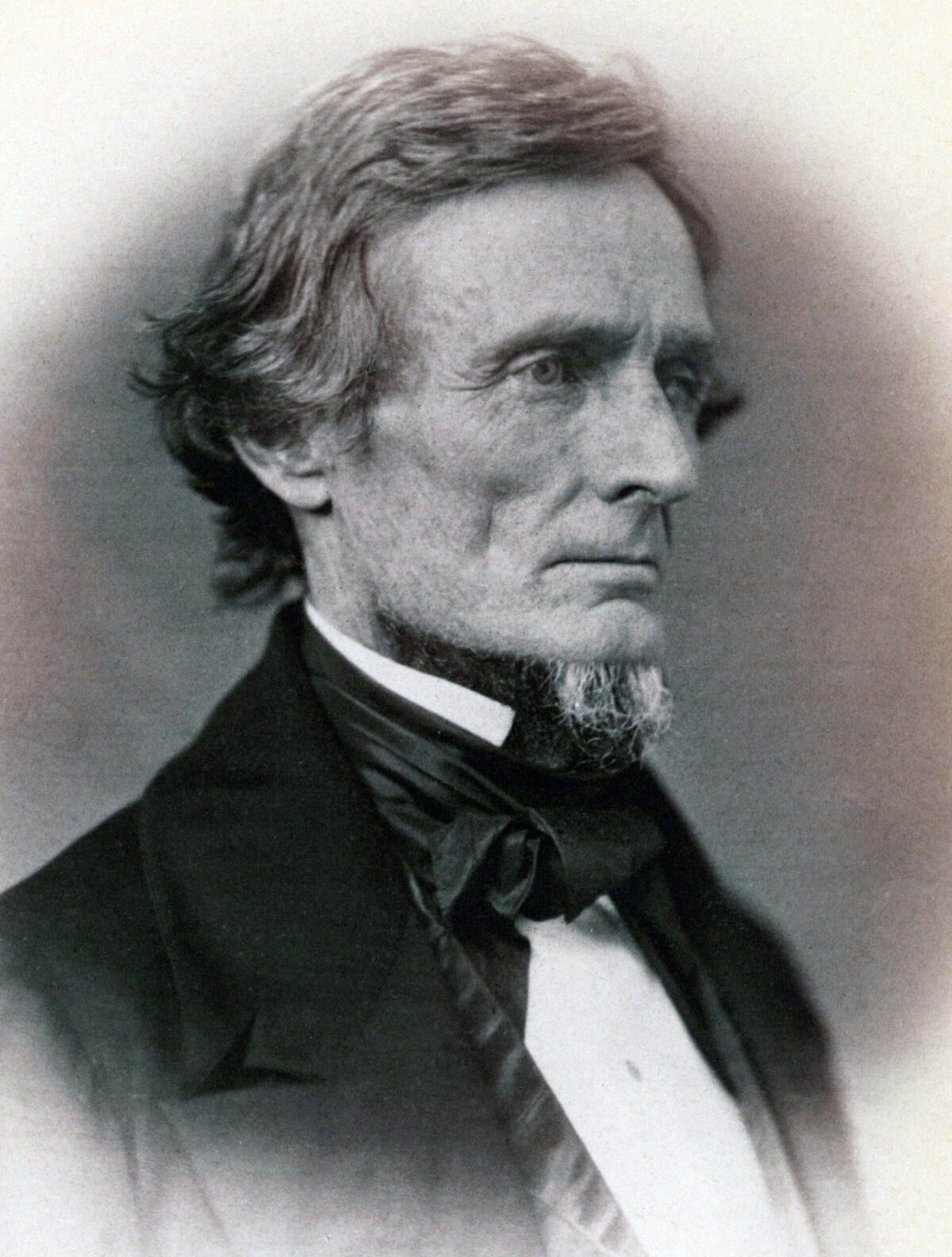

Jefferson Davis’ chief occupation before 1861 was politics. He had other vocations, of course. As a young man he served as an officer in the U.S. Army, and in the mid-1830s he became a cotton planter. But from his selection in 1844 as a Democratic presidential elector in Mississippi he had concentrated on politics, dedication that resulted in a notable public service career—the U.S. House of Representatives, the U.S. Senate and the Cabinet. In the 1850s Davis had established himself as the dominant political figure in Mississippi, and by the end of the decade he was a major leader in not only the Senate but the nation as a whole.

From 1845, when he entered the House, until the breakup of the Union, Davis was an absentee planter, spending considerably more time in Washington than in Mississippi. In 1860 he was a professional politician and an extraordinarily successful one. When the cataclysm of the secession crisis ripped the nation, it also tore Davis. He was no fire-eater, no sectional extremist, and though he believed in the constitutionality of secession, he never advocated leaving the Union. He always identified himself as an American.

Rejecting the notion propounded by Republican politicians such as Abraham Lincoln that the nation could not exist half-slave and half-free, Davis pointed to great American heroes like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson and Zachary Taylor, slave owners all. Furthermore, in his judgment, the Constitution protected slavery, a view shared by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Even Lincoln’s election in 1860 did not turn Davis into a secessionist. After all, fully 60 percent of American voters cast their ballots for candidates who had no problem with slavery in the nation. In the Senate he unsuccessfully strove to avoid the disintegration of the Union. The failure of the Union massively affected Davis. The old politics, the politics he had mastered, had failed. He believed ambition and selfishness had led men to lose sight of the main goal, preserving the Constitutional Union of the Founding Fathers. He termed the day of his farewell remarks to the Senate “the saddest day of my life.”

For Davis the creation of the Confederate States of America in February 1861 opened a new political world and forced him to find a new political center. Chosen president, he discovered that core in his total commitment to the fledgling nation. “Our cause is just and holy,” he announced to the Confederate Congress in April 1861. Over the next four years words like just, holy, noble, sacred, sacrifice filled his public statements and pervaded his personal letters.

As president of the infant nation, Davis would make an indelible imprint on the political world of the Confederacy. That world included the military, for the Confederate Constitution, like its U.S. counterpart, designated the president as commander in chief of all armed forces. The military quickly assumed a central place because almost from birth the Confederacy found itself immersed in the cauldron of war.

Too often those who discuss Confederate military history treat it as beyond or apart from politics, except for the individual politics of personality squabbles. That approach is absolutely wrong. The entire subject of Confederate military history is in a basic sense political.

This reality did not escape Jefferson Davis. His antebellum background prepared him for it. He understood that political consideration formed the keystone of Confederate military pol icy. To a wartime aide he spoke of having “to conduct a war and a political campaign as a joint operation,” and he never forgot “the necessity of consulting public opinion instead of being guided simply by military principles.”

Examining Davis’ actions and decisions in three critical areas, each central to the politics of command— strategic fundamentals, major appointments and command relationships—helps us to understand what occurred during his presidency.

First, strategic fundamentals: At the onset of the conflict Confederates considered the size of their country, stretching more than 1,000 miles from the Atlantic Ocean westward across the Mississippi to Texas, a military asset. The Union faced an immense task, to subdue a widely scattered population and occupy so much territory. But at the same time Davis had to make choices about which portions to defend, should the United States mount an attack sufficiently powerful to threaten the entire border. When the Union did make such an assault, the Confederate defenses were stretched far too thin and broke at several points. Since the 1860s, critics have pounded Davis for failing to concentrate his forces at those points.

Such criticisms assume that Davis as commander in chief dealt with military problems as hermetically sealed from all other influences. Davis, however, understood that decisions about what to defend in his far-flung country were political as well as military. In 1863 he informed his commander in the vast Trans-Mississippi theater that “the general truth, that power increased by the concentration of an army, is, under our peculiar circumstances, subject to modification.” He went on to amplify, “The evacuation of any portion of territory involves not only the loss of supplies, but in every instance has been attended by a greater or less loss of troops….” As a result, each situation presented “a complex problem to solve.”

After the war he addressed critics, saying, “It was easy to say other places were less important and it was the frequent plea, but if it had been heeded as advised, dissatisfaction, distress, desertions of soldiers, opposition of State Govts would have soon changed ‘apathy’ into collapse.”

For many Confederates the great motive to fight came from defense of home against an invader. Home meant locality, maybe the state, but often not beyond those boundaries. In 1862 this was especially true in Davis’ far west, the Trans-Mississippi, where the commanding general reported citizens and state troops as “luke warm” and “disheartened.” The president fully comprehended that situation, assuring political leaders that “no effect should be speared [sic] to promote the defense of the Trans-Missi. Dept….”

Throughout the war Davis strove to meld the political and military. He did not always succeed, a reality that he recognized. Davis, in fact, should get substantial credit for comprehending the fundamental political certainty that he had to face in his strategic decisions.

Davis had to contend with the civilian-professional leadership quandary. As a West Point alumnus and a former Regular Army officer, Davis preferred professionals—every full general he named was a West Point graduate. Yet he knew he would have to appoint political generals, so he made his appointments with two considerations. First, he insisted his political generals have a positive impact on his administration and his cause. Second, even when dealing with professionals, he listened seriously to his political leaders.

Discussing appointments with Governor Isham Harris of Tennessee in the summer of 1861, Davis made clear his awareness of the political value accruing from the right choices. Harris expressed concern that the president had paid too little attention to previous political affiliations in awarding army commissions to Tennesseans. According to the governor, “positive political necessity” required more military slots for former Whigs. Explaining his initial appointments, Davis responded that “the magnitude and supreme importance of the present crisis” had caused him “to forget the past.”

Likewise, in the summer of 1862 Davis faced a nagging political problem caused by John C. Pemberton, a Philadelphia-born West Pointer who followed his Virginia wife into the Confederacy. Pemberton enjoyed an excellent military reputation without having really earned it. The president saw Pemberton as a selfless patriot committed to the Confederate cause. In the spring of 1862, Maj. Gen. Pemberton assumed his duties in Charleston.

South Carolinians, though, never accepted Pemberton, and Governor Francis W. Pickens urged Davis to remove the general. Davis defended Pemberton, amazingly calling him “one of the best Generals in our service,” but realized that political considerations required a change. When he reassigned Pemberton, he replaced him in September with General P.G.T. Beauregard, the victor of Fort Sumter.

By the summer of 1862, Davis had decided that Beauregard, the first Confederate military hero, was no longer fit to head a major field army and the South Atlantic slot was a good post for him because it entailed chiefly coastal defense requiring engineering skills that Beauregard possessed.

The following year Davis counseled his Trans-Mississippi commander, General Edmund Kirby Smith, on the need to cultivate state officials. He knew Smith could never meet all local demands, but he advised him, “much discontent may be avoided by giving such explanations to the Governors of the States as will prevent them from misconstruing your action….” Davis concluded that the governors could become Smith’s “valuable coadjutors.”

Heeding his president’s advice, Smith invited notables from the four states in his department to meet in Marshall, Texas. Governors, members of Congress, and other prominent men from Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri and Texas attended and published proceedings proclaiming their confidence in the cause. In this instance, civil-military relations meshed perfectly.

Up to that point in the war, Davis had not betrayed his prewar political professionalism. But in all politics, personal relationships are critical; they often determine success or failure. By most accounts Davis too often failed here. But why?

Davis’ reaction to the disruption of the Union holds the basic clue. The failure of the old Union delivered a severe emotional and psychological blow to Davis. The Confederacy must not fail, and to it he gave his absolute commitment. Davis believed no room remained for the human foibles that had brought down the Union. Ambition, greed, vanity and selfishness had to be banished from this sacred crusade. In his own mind he was utterly selfless. “The cause” he told a Raleigh, N.C., audience in January 1863, “is above all personal or political considerations, and the man who, at a time like this, cannot sink such considerations, is unworthy of power.”

The best way to understand his motivation perhaps is to observe how he dealt with three of his key generals. Each instance was critical in its own way for his performance as commander in chief and for his cause.

At the onset of the war President Davis liked and respected Joseph E. Johnston. Then late in the summer of 1861, Davis sent to Congress the seniority list for the five full generals. Much to his dismay, Johnston found himself ranked fourth, not first, as he assumed. Johnston was insulted; he was the only Confederate officer to have held a permanent brigadier generalship in the pre-1861 U.S. Army.

Davis claimed to have followed West Point class and standing within a class— Samuel Cooper, 1815; Albert Sidney Johnston, 1826; Robert E. Lee and Joseph Johnston, 1829 (second and thirteenth respectively); and Beauregard, 1838. He said he placed Albert Johnston and Lee ahead of Joe Johnston because they had been line officers, whereas Joe Johnston’s generalship derived solely from his staff assignment as quartermaster general. In addition, Davis asserted that considering prewar U.S. Army rank applied neither to Lee nor Joe Johnston, because both had entered Confederate service from the Virginia state forces, where Lee had higher rank. Although there was some validity there, Davis was clearly rationalizing his actions.

Johnston was infuriated and hurt, and penned a lengthy, agitated letter to the president in which he announced: “I now and here claim, that notwithstanding these nominations by the President and their confirmation by the Congress, I still rightfully hold the rank of first general in the Armies of the Southern Confederacy.”

Davis was taken aback. Johnston’s language was surely inappropriate from a military subordinate to a superior; but even more important the letter told Davis that his general cared more about rank than the cause. He replied: “I have just received and read your letter of the 12th instant. Its language is, as you say unusual; its arguments and statements utterly one-sided, and its insinuations as unfounded as they are unbecoming.”

Never again during the war did the two men correspond about this matter, though its memory embittered Johnston for the rest of his life. Johnston had revealed the human flaws of pride and ambition, which Davis could not countenance. Davis, however, still respected Johnston’s military ability and gave him important commands, the Department of the West in the fall of 1862 and the Army of Tennessee in December 1863. But Johnston began associating with anti-Davis politicians.

At almost the same time Davis’ relationship with Joe Johnston began to sour, his faith in Beauregard also degenerated. The president was pleased with Beauregard at Fort Sumter, and so delighted with First Manassas that he promoted the officer to full general in the field. Davis quickly became disillusioned, however.

The first instance occurred in the fall of 1861, with Beauregard’s official report on First Manassas. The general filled this report with puffery, strongly implying that he alone had made victory possible and would have marched on Washington but for Davis’ remonstrance. In addition, he pointedly noted that even before the battle, the president had quashed his offensive plan. He sent the report to friendly politicians as well as the War Department.

Davis considered such self-advertisement unacceptable. A disgusted commander in chief told his general that if they “did differ in opinion as to the measure and purpose of contemplated campaigns, such fact could have no appropriate place in the report of the battle.” The president said he “labor[ed] assiduously in my present position,” and “my best hope has been, and is, that my co-laborers, purified and elevated by the sanctity of the cause they defend, would forget themselves in their zeal for the public welfare.”

Despite his displeasure, Davis stuck with Beauregard, sending him west in early 1862 to assist Albert Sidney Johnston. Following Johnston’s death at Shiloh in April, Beauregard assumed command of the Army of Tennessee, concentrated at Corinth, in north eastern Mississippi. He informed the War Department that he would hold it “to the last extremity.” But when a powerful Union force approached, he re treated 50 miles south to Tupelo.

Then in mid-June Beauregard, without requesting permission from the War Department and even without prior notification, placed himself on sick leave and departed, placing his deputy in charge. A chronically ill Davis was appalled. Once more, in Davis’ view, Beauregard had placed his personal concerns ahead of duty and cause; on June 20, he removed Beauregard.

Beauregard was furious. Feeling that a presidential vendetta underlay his removal, he castigated Davis as “that living specimen of gall and hatred.” The gulf between the two men steadily deepened. Davis put Beauregard in the military wilderness of coastal protection until the final fall of the war, when he was utterly desperate for a senior commander.

In direct contrast to his perception of Joseph Johnston and Beauregard as men who could not or would not subordinate the personal to the cause, Davis viewed Braxton Bragg as a selfless, dedicated patriot. That loyalty began at Pensacola, Fla., Bragg’s initial posting. When his command there was decimated to fill the main armies, Bragg did not complain. He did his work of organizing and training. That impressed Davis, who saw a general who valued the cause above himself. To his brother, the president wrote positively about Bragg, noting the general was in “no degree a courtier.” In the winter of 1861-62 Bragg went to A.S. Johnston’s command. Positive reports from friends and family members on Bragg’s performance at Shiloh and in Mississippi reinforced Davis’ initial judgment. After Shiloh he made Bragg a full general.

Davis’ conviction about Bragg had far-reaching repercussions when the president stuck with Bragg as commander of the Army of Tennessee far longer than he should have. In fact, arguably his most disastrous command decision in the war was retaining Bragg in October 1863, even after a personal visit to the army revealed the venomous relations rampant among its general officers. Just a month later the Army of Tennessee suffered a crushing defeat at Missionary Ridge in Chattanooga, and both the general and the president realized a change was inevitable. Bragg resigned his command of the Army of Tennessee.

Consumed with leading a holy mission and convinced of his own super human commitment to the Confederacy, Davis could not deal effectively with anyone whose commitment was less total than his own. In the case of Johnston and Beauregard, he did not act toward them in a manner to get the most from them despite their flaws. With Bragg, Davis’ loyalty to his ideal overrode his judgment.

Focusing on the politics of command reveals Davis’ strengths and weak – nesses as commander in chief. In a great irony, his incredible commitment to the Confederacy undermined its chance for success.

William J. Cooper Jr. is Boyd Professor of History at Louisiana State University. This article is excerpted from his book Jefferson Davis and the Civil War Era, forthcoming from LSU Press in October 2008.

Originally published in the August 2008 issue of Civil War Times. To subscribe, click here.