During his presidency, he spent most of his waking hours directing the Confederate war effort.

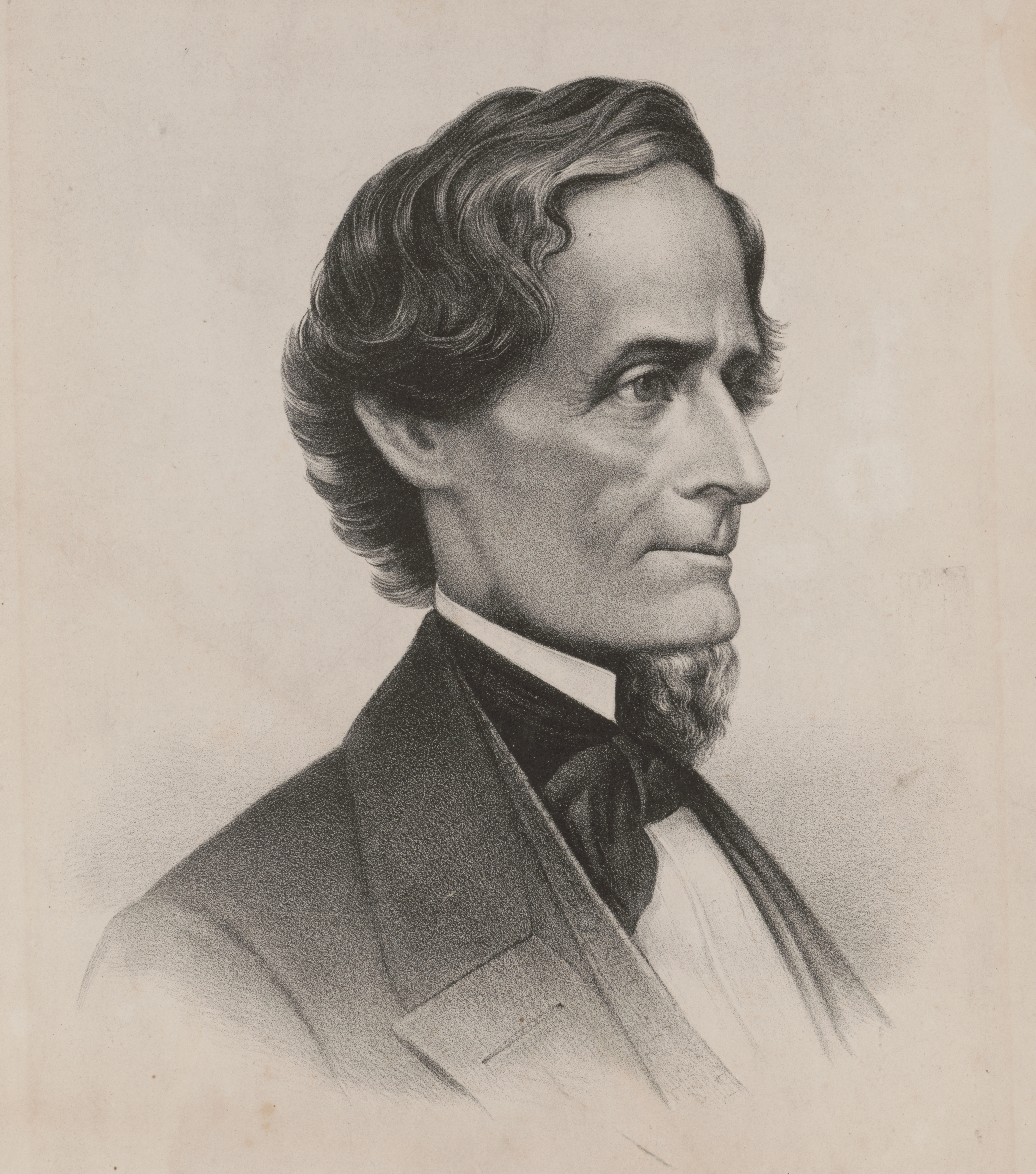

As president of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis was in charge of policy, national strategy, and military strategy and operations during the four and a half years of the Civil War. As commander in chief of the newly formed Confederate army and navy, his workaholic devotion to detail led him to spend most of his time on military matters. Indeed, given his West Point training (1824–1828) and his field experience in the Mexican War, many expected him to take personal command of the CSA forces—and starting with his surprise appearance at the first Battle of Manassas in July 1861, he very nearly did just that. In Embattled Rebel, his new biography of Davis, James McPherson says that as the fighting approached the new Confederate capital in Richmond, Virginia, the president “left his office, mounted his horse and rode toward the sound of the guns.”

“Events have cast on our arms and our hopes the gloomiest shadows,” Davis lamented to General Joseph E. Johnston in February 1862. The president summoned Johnston to a strategy conference with cabinet members on February 19 and 20. For many hours they discussed the vulnerability of Johnston’s army at Centreville to a flanking movement by McClellan’s large force via the Occoquan or Rappahannock River. They agreed that Johnston should pull back to a more defensible position south of the Rappahannock. But the wretched condition of roads caused by winter rains and the chaotic state of the railroads made a quick withdrawal impossible. Davis ordered Johnston to send his large guns, camp equipage, and huge stockpiles of meat and other supplies southward as transportation became available, and to prepare to retreat with the army when he received definite orders.

In early March, however, Johnston began a precipitate withdrawal when his scouts detected Federal activity that he thought was the beginning of McClellan’s flanking movement. Without informing Richmond (he feared a leak), Johnston fell back so quickly that he was compelled to leave behind or destroy his heavy guns, ammunition, and mounds of supplies, including 750 tons of meat and other foodstuffs. In Richmond Davis heard rumors of this destruction and retreat, but as he later told the general, “I was at a loss to believe it.” When he finally heard the truth from Johnston on March 15, the president’s distress at the losses the Confederacy could ill afford was acute.

Davis’s confidence in Johnston had been waning for some time. As things went from bad to worse during February and March, the president decided to recall Robert E. Lee from the southern Atlantic coast to become general in chief of all armies. Davis and Lee had known each other since their days at West Point (Davis graduated one year ahead of Lee). They had worked together cordially in the early months of the war when Lee served as a military adviser to the president after the government moved to Richmond. Davis used Lee as a sort of troubleshooter, sending him in July 1861 to western Virginia to regain control of the region from Union forces, and to South Carolina in November to reorganize coastal defense. For reasons largely beyond his control, Lee had failed to accomplish much in what became West Virginia and had met with partial success along the southern Atlantic coast only by withdrawing Confederate defenses inland beyond reach of Union gunboats.

Despite this mixed record, Davis retained his faith in Lee’s abilities and wanted him by his side. The president had his congressional allies introduce a bill to create the position of “Commanding General of the Armies of the Confederate States,” intending to name Lee to the post. But Davis’s critics in Congress, who blamed him for Confederate reverses, amended the bill to enable the “commanding general” to take direct control of any army in the field without authorization from the president. Davis believed that this provision would usurp his constitutional powers as commander in chief, and he vetoed the bill on March 14. A day earlier he had issued an order assigning Lee to duty in Richmond and charging him “with the conduct of military operations…under the direction of the President.”

Lee’s first task was to help Davis decide what to do about the situation in Virginia. From his desk in Richmond, Lee instructed Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson to make diversionary attacks with his small army in the Shenandoah Valley to prevent the Federals from concentrating all of their troops against Richmond. During the next two months Jackson carried out these orders in spectacular fashion. Meanwhile, McClellan’s army began landing near Fort Monroe at the tip of the peninsula in Virginia formed by the James and York Rivers, 70 miles southeast of Richmond. When the Federals advanced toward the Confederate defenses held by Major General John B. Magruder’s 12,000 troops, Davis and Lee ordered Johnston to send part of his army from the Rappahannock to Magruder. As the Union buildup continued, they instructed him to bring his whole army to the peninsula. Johnston proceeded to do so, but after inspecting Magruder’s line at Yorktown, he recommended that the Confederates withdraw all the way back to Richmond, concentrate the Virginia forces there, and strip the Carolinas and Georgia of troops to fight the decisive battle of the war at Richmond. Winning there, they could then reoccupy the regions temporarily yielded to the enemy.

Here was a bold suggestion for a high-risk strategy of concentration for an offensive-defensive of the kind later associated with Lee. But on this occasion Lee opposed the idea. In an all-day meeting of Davis, Lee, Johnston, and Secretary of War Randolph on April 14, Lee and Johnston discussed the matter at great length. Lee argued for making the fight at Yorktown, where the big guns at the Gloucester Narrows on the York River and the CSS Virginia on the James River would protect the army’s flanks. An old navy man, Randolph pointed out that pulling back from Yorktown would mean abandoning Norfolk with its Gosport Navy Yard, where the Virginia had been rebuilt from the captured USS Merrimack. Davis listened carefully to the arguments, took an active part in the discussion, and finally decided in Lee’s and Randolph’s favor. The Confederates would make their stand at Yorktown, where Johnston took command of 60,000 troops facing McClellan with 110,000.

Instead of attacking, McClellan dug in his siege artillery and prepared to pulverize the Confederate defenses. This preparation continued for several weeks while the armies skirmished but did little damage to each other. Despite having been overruled by Davis, Johnston still intended to evacuate the Yorktown line without a fight. He delayed that move until McClellan was ready to open with his heavy artillery. Johnston failed to keep Davis and Lee informed of his intention until the last minute on May 1, when he told the president that he must pull out the next night. Davis was shocked. He replied that such a sudden retreat would mean the loss of Norfolk and possibly of the Virginia and other ships under construction there. Johnston consented to wait—for one more day. On the night of May 3–4 his army stealthily left the Yorktown line and began a retreat toward Richmond. The Confederates fought a rearguard battle with the cautiously pursuing Federals at Williamsburg, and continued to a new line behind the Chickahominy River 20 miles from Richmond. Norfolk fell to the enemy, and the Virginia’s crew had to blow her up because her draft was too great to get up the James River.

Davis was dismayed by these developments. A congressman reported that he found the president “greatly depressed in spirits.” Davis’s niece from Mississippi was visiting the Confederate White House at the time. She wrote to her mother that “Uncle Jeff. is miserable.…Our reverses distressed him so much.… Everybody looks drooping and sinking.…I am ready to sink with despair.” Davis and several cabinet members sent their families away from Richmond for safety. The secretary of war boxed up his archives ready for shipment before the capital fell. The Treasury Department loaded its specie reserves on a special train that kept steam up for an immediate departure.

Davis allowed his anguish to leak into a letter to Johnston lamenting “the drooping cause of our country.” The ostensible purpose of the letter was to prod Johnston into carrying out Davis’s orders to group regiments from the same state together in brigades as a boost to morale. “Some have expressed surprise at my patience with you when orders to you were not observed,” the president told his general. Johnston recognized this rebuke for what it was, an expression of exasperation with Johnston’s conduct of the campaign. If he had received such a letter from someone who could be “held to personal accountability,” Johnston told his wife, he would have challenged him to a duel.

In this time of troubles, Davis turned to religion. He had been attending St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond and had grown friendly with its rector, the Reverend Charles Minnigerode. Davis could not remember whether he had been baptized as a child, so he asked Minnigerode to baptize him and confirm him as a member of the church on May 6. One of Davis’s newspaper tormentors, the Richmond Examiner, waxed sarcastic about this event: “When we find the President standing in a corner telling his beads, and relying on a miracle to save the country, instead of mounting his horse and putting forth every power of the Government to defeat the enemy, the effect is depressing in the extreme.”

But Davis was in fact mounting his horse and exerting all of his energy to try to defeat the enemy. A fine horseman, Davis was in the habit of riding out in the afternoon for exercise and diversion. He used these occasions to visit army headquarters on the Chickahominy and the batteries placed at Drewry’s Bluff on the James River seven miles from Richmond to stop the Union navy. Those guns did indeed drive back Northern warships, including the Monitor, on May 15, saving Richmond from the fate of New Orleans three weeks earlier, when the city had surrendered with naval guns trained on its streets.

But Richmond still seemed in great danger from General McClellan’s large army approaching the capital at a snail’s pace. Although Johnston chose not to reveal his plans to Davis (or Lee), the president expected him to defend the line of the Chickahominy and even to launch a counterattack if he stopped McClellan along that sluggish stream. Davis still had not lost entire faith in Johnston, despite his previous disappointments. “As on all former occasions,” he told the general on May 17, “my design is to suggest not to direct, recognizing the impossibility of any one to decide in advance and reposing confidently as well on your ability as your zeal it is my wish to leave you with the fullest powers to exercise your judgment.”

Unknown to Davis, Johnston had already decided to withdraw to a new position just three or four miles east of Richmond. When the president rode out the next day to visit Johnston on the Chickahominy, he was taken aback when he encountered the army before he had ridden more than a few miles. Davis confronted Johnston and asked why he had pulled back so close to the capital. The general replied that the ground was so swampy and the drinking water so bad in the Chickahominy lowlands that he had moved to better ground and a safer supply of water. Davis was unnerved. Do you intend to give up Richmond without a battle? he asked. Johnston’s reply was equivocal. The president responded with asperity. He told Johnston, according to one of Davis’s aides who was present, “that if he was not going to give battle, he would appoint someone to the command who would.”

Davis rode back to Richmond and summoned his cabinet and General Lee to a meeting the following day. He also asked Johnston to attend, so that everyone could learn his intentions. The afternoon of the meeting, Davis wrote to his wife: “I have been waiting all day for [Johnston] to communicate his plans.… We are uncertain of everything except that a battle must be near at hand.” Johnston never showed up, but Davis went ahead with the conference, where he expressed his anxiety about the fate of Richmond. According to Postmaster General John Reagan, Lee became emotional. “Richmond must not be given up,” he declared. “It shall not be given up.” As Lee spoke, Reagan recalled, “tears ran down his cheeks. I have seen him on many occasions and at times when the very fate of the Confederacy hung in the balance, but I never saw him show equally deep emotion.”

The next day Davis assured a delegation from the Virginia legislature that Richmond would indeed be defended. “A thrill of joy electrifies every heart,” wrote the diary-keeping War Department clerk John B. Jones. “A smile of triumph is on every lip.” Johnston finally seemed to get the message. He discovered that McClellan had crossed to the southwest bank of the Chickahominy with part of his army, leaving the rest on the other side. Johnston informed Lee that he intended to cross the stream with three divisions and attack the force on the northeast bank on May 22. Davis had earlier discussed precisely such a tactical operation with Lee, so he approved Johnston’s plan. On the 22nd the president rode out to the bluff overlooking the Chickahominy, then down to the river itself, to “see the action commence,” as he wrote to his wife. But he found nothing happening and no one to tell him why the attack had been called off. Only later did General Gustavus Smith, whose division was to lead the attack, tell Davis that a local citizen had informed him that the enemy was strongly posted behind Beaver Dam Creek, so he had decided not to attack. This was not the first time that Smith had frozen under pressure. Davis was disconsolate. “Thus ended the offensive-defensive programme,” he wrote, “from which Lee expected much, and of which I was hopeful.”

Almost the same scenario repeated itself exactly a week later, on May 29. Once again Johnston planned to attack McClellan’s right flank north of the Chickahominy, and once again he called it off without informing Davis. The president discovered the cancellation only after riding out to the river on another futile mission. Johnston had changed his mind and decided to assault the two corps south of the Chickahominy and nearest Richmond. The general later explained that he did not tell Davis of this change “because it seemed to me that to do so would be to transfer my responsibilities to his shoulders. I could not consult him without adopting the course he might advise, so that to ask his advice would have been, in my opinion, to ask him to command for me.”

Johnston’s peculiar notion of the correct relationship with his commander in chief meant that Davis first learned of the general’s changed plan of attack when he heard artillery firing on the afternoon of May 31. He quickly left his office, mounted his horse, and rode toward the sound of the guns. When he arrived near the village of Seven Pines (which gave its name to the battle), he saw Johnston riding away toward the front. Davis’s aides were convinced that the general left to avoid the president. The battle was going badly for the Confederates. Major General James Longstreet’s division had taken the wrong road and blocked the advance of other divisions. The attack started late, and although it initially succeeded in routing one Union corps, reinforcements streamed across an almost flooded bridge over the Chickahominy and drove the Confederates back.

Davis came under artillery and musket fire as he and his aides tried to rally retreating soldiers. A reporter for a Memphis newspaper described the president “sitting on his ‘battle horse’ immediately behind our line of battle.…I was much struck with the calm, impassive expression of his countenance and his proud bearing as he sat erect and motionless, intently gazing at the enemy.…Bullets whistled plentifully around, but he never bootled his eye for them.”

Davis issued orders and sent couriers for reinforcements, but as dusk approached it was clear that the Confederate attack had ground to a halt. At that moment, stretcher bearers passed the president’s party carrying a seriously wounded Johnston to the rear. All animosity forgotten, Davis rushed to Johnston’s side and spoke to him with genuine concern. “The old fellow bore his suffering most heroically,” Davis wrote to his wife. It was obvious that Johnston would be out of action for several months. As Davis and Lee rode together back to Richmond that night, the president told him that he was now the commander of what Lee would soon designate the Army of Northern Virginia. A new era would dawn with that army’s new name and new commander. “God will I trust give us wisdom to see and valor to execute the measures necessary to vindicate the just cause,” wrote Davis as he entered into his new command relationship with Lee.

James M. McPherson is the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Battle Cry of Freedom. This is excerpted from Embattled Rebel, by James M. McPherson, published by The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, October 2014. Copyright © by James McPherson.

Originally published in the January 2015 issue of Military History Quarterly. To subscribe, click here.