In the days after Japan’s December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, one woman was subjected to more intense vituperation than any other American. Letters and wires called her “a disgrace and a traitor”; one stated, “when concentration camps open you should be occupant number one.” The object of this vilification was Republican Congresswoman Jeannette Rankin, the representative of Montana’s First District.

In Dillon, in the southwest corner of the state, the Kiwanis and the Rotary Club fired off a joint telegram to Rankin, reading: “You have done a great disservice to the state of Montana and to the American People.” The Pioneer newspaper in Big Timber suggested “she be publicly spanked on the floor of the House.” Radio commentators used such harsh language in denouncing her that some stations masked their broadcasts with music.

The transgression that earned Rankin, 61, such calumny happened just after 1:00 p.m. on December 8 in the Capitol in Washington, as Irving Swanson, a clerk in the House of Representatives, read members roll call, recording their votes on the fateful resolution declaring war against Japan. “Yea” after “yea” came in like an echo as Swanson read the names at a pace of 20 per minute until he got to Rankin, who in a firm voice announced her stance: “No.” Other House members began hissing.

It was the only vote in either house of Congress against the declaration of war for which President Roosevelt had asked.

For Rankin it was a repeat performance. She was then in her second term in the House. Her first had begun on April 2, 1917, when she was sworn in as the first woman to serve in the United States Congress. Five days later—on April 7—Congress voted on a resolution for entry into World War I and she had voted “no” then as well.

In 1917, however, ambivalence about the country going to battle in Europe was not uncommon. The mood in the United States following the Pearl Harbor attack was quite different. On the Sunday of the attack, Rankin and her sister Edna were on a train from Washington to a speaking engagement in Detroit when she learned that Roosevelt would be addressing a joint session of Congress the next day. She got off the train in Pittsburgh and returned to the Capitol. At her home the phone rang nonstop. The first call was from her brother Wellington, her top political adviser and fundraiser for her political campaigns, urging her not to repeat her World War I “no” vote. So many other callers and visitors repeated that message that Rankin felt she had to escape.

“I didn’t let anybody approach me,” she later told her biographer, Hannah Josephson. “I got in my car and disappeared. Nobody could reach me. I just drove around Washington and got madder and madder” until it was time to go to Congress for the presidential address.

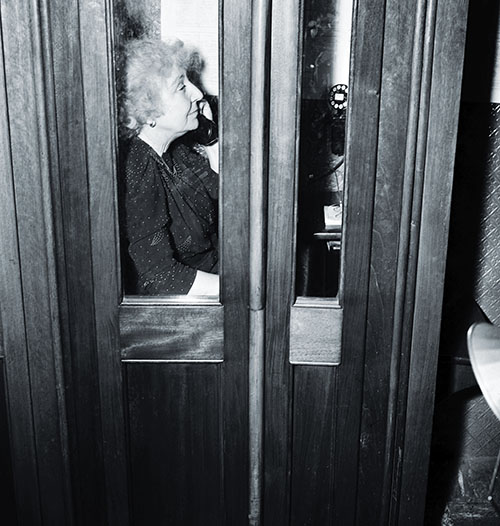

A lifelong pacifist, Rankin did not waver in her determination to vote against the war resolution. But on the day after the shocking and devastating Pearl Harbor attack, the country was in no mood for pacifism. Rankin’s “no” subjected her to such an immediate onslaught from reporters that she retreated to the members’ cloakroom where she hid in a phone booth and called for Capitol Police to escort her back to her office.

RANKIN’S OPPOSITION TO WAR should not have been a shocker. Her anti-intervention position was a key reason for her 1940 campaign for Congress. “If I don’t run,” Rankin said 44 years later to a student writing his master’s thesis about her career, “the women who don’t want war will have no one to vote for.”

Rankin had been an ardent advocate for women’s suffrage; it was largely through her efforts that women won the right to vote in Montana in 1914—two years before she was elected to Congress. In 1910, Denver news reporter and women’s rights activist Minnie J. Reynolds had persuaded Rankin that pacifism was an inherent part of feminism. “The women produce the boys and the men take them off and kill them in war,” Reynolds argued. Rankin’s reading of Benjamin Kidd’s 1918 book, The Science of Power, solidified her commitment to Reynold’s feminist-pacifist ideology. Kidd found in men a natural inclination to battle while he found in women a preference for peaceful settling of disputes. Rankin called Kidd’s opus the “most important book” she had ever read.

Not only had she opposed American participation in World War I, but in the interwar years she was active in pacifist organizations; she was the chief lobbyist for the National Council for the Prevention of War from 1929 until she left the job to campaign for reelection to Congress in 1940. The antiwar slogan under which she successfully ran was “Keep Our Men Out of Europe.”

As soon as Rankin got back to Congress in January 1941, she organized a grassroots campaign of letters from mothers opposing American entry into the war then raging abroad. Two months later, she opposed Roosevelt’s Lend-Lease legislation. And in May, she gave a Mother’s Day speech on the House floor in which she declared: “There is nothing in the world the mothers of this country would like on this Mother’s Day so much as an assurance that their sons are not going to war.”

Knowing her stance was a lost cause, she nonetheless pressed her anti-intervention views. In June, she offered an amendment to budget authorization legislation for the War Department that read: “no appropriation in this act shall be used to send our army or air forces to fight in foreign lands outside of the Americas or our insular possessions except in case of attack.” Rankin’s other fruitless legislative initiatives to counter the nation’s drift toward war included attempts to stall the draft until voters had approved conscription, to ban the arming of civilian ships, and to remove the death penalty for wartime sabotage.

She was an astute enough politician to know that in her solitary “no” on the declaration of war she was bucking the mood of her constituents. Shortly after she got back to her office, she hastily drafted a statement trying to explain her vote. “I believed that such a momentous vote—one which would mean peace or war for our country—should be based on more authentic evidence than the radio reports now at hand,” she wrote in the communication to Montana newspapers. “Sending our boys to the Orient will not protect this country…. Taking our army and navy across thousands of miles of ocean to fight and die cannot come under the heading of protecting our shores.”

On December 11 she let the record show she was in the House but not taking a position by saying merely “present”—in such a whisper that the clerk had to ask her to repeat her vote—on the resolutions of war against Germany and Italy. She was not in Washington in June 1942 when Congress declared war on Bulgaria, Hungary, and Rumania.

As she served out her term through 1942, Rankin had lost her political clout. She often appeared to be going through the motions without much commitment. While in 1941 she had virtually never missed a vote, by the fall of 1942 she was absent for 80 percent of recorded votes in the House. On the first anniversary of the vote declaring war on Japan, she entered into the Congressional Record a long analysis of how the United States was, in her view, essentially tricked into World War II by Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. “Three years before Pearl Harbor, Britain’s imperialists had figured out just how to bring the United States once more to their aid,” she wrote. She saw as part of the plot Roosevelt’s 1940 decision to impose sanctions on Japan in hopes of fomenting retaliation.

HER DECEMBER 8 “NO” VOTE did draw some admiration for the courage she displayed. “Lord, it was a brave thing,” famed Kansas editor William Allen White wrote in his Emporia Gazette, “and its bravery somehow discounts its folly.” But Rankin’s views found little support.

It had not been that way before. Forty-nine other House members voted along with her 24 years earlier when she cast her vote against American participation in World War I. She received extra protection then against political retaliation when the leader of the House Democrats, Claude Kitchin of North Carolina, also voted “no,” as well as six senators. In 1917, opposition about sending Americans to fight in Europe was particularly strong in Western states like Montana. As a result, Rankin’s anti-intervention stance did not hurt her politically in the 1918 election. But a bad decision did.

Rankin had originally been elected to Congress as one of Montana’s two at-large House members. Before the 1918 election, the legislature changed the process and set up two separate congressional districts. Rankin would have had to run in the Second District, where she felt a Republican had no chance of winning, so she set her sights on the U.S. Senate, hoping to defeat incumbent Democrat Thomas Walsh. After losing the Republican primary for the Senate seat, she ran as an independent, coming in third with about 20 percent of the vote. The irony: a Republican, Carl Riddick, won the House seat Rankin had feared to compete for.

Rankin knew that the second vote in her political career against a declaration of war was political suicide. Her brother Wellington had warned her “Montana is 100 percent against you.” So she did not even try to run for reelection in 1942. Her replacement in the House was Mike Mansfield, who went on to serve 34 years in Congress, the final 16 as Senate majority leader.

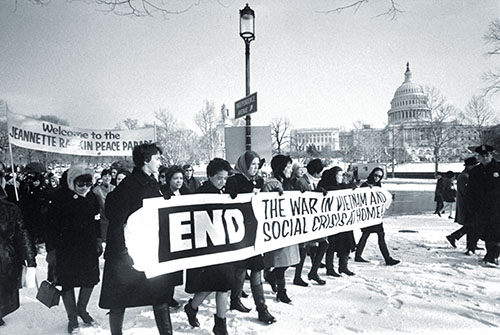

While her elective career was over, her efforts as a crusader were not. She continued to preach pacifism, traveled frequently to India to confer with Mahatma Gandhi, and found an increasingly receptive audience for her antiwar rhetoric as the United States became mired in the Vietnam War. In fact, before she died on May 19, 1973, at age 92 she was considering emphasizing her opposition to the war by running for Congress again.

In 1985, the state which had once been 100 percent against Rankin selected her to join Western painter Charles Marion Russell as its two representatives among the 100 famous Americans whose statues are on display in the U.S. Capitol. ✯

This story was originally published in the November/December 2016 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.