James Reese Europe enjoyed pride of place in two Manhattan parades during 1919. The first was a cheering February 17 welcome to the soldiers of the U.S. Army’s 369th Infantry, returning after fighting in France to march up Fifth Avenue behind the battalion’s famed band, which Lieutenant Europe led.

The second event, less than three months later, was a funeral procession honoring Jim Europe, slain at 39. Both events were notable, because James Europe, like the rank and file of the 369th, was black. He also was the man who inserted into the mainstream the beat that became jazz and who insisted that white audiences and managers show black composers and black musicians respect. “Before he arrived in New York, jazz was a little-known word and if known at all was probably a vulgarity,” biographer R. Reid Badger wrote. “By the time of his death it had become an accepted term for describing a musical revolution.”

Europe certainly acknowledged racism, but, he told the New York Tribune, “I am not bitter about it. It is, after all, but a slight portion of the price my race must pay in its at times almost hopeless fight for a place in the sun. Some day it will be different and justice will prevail.”

Those 1919 parades mattered monumentally to black Americans, who turned out in thousands for each. Summoning an image of the regimental victory march, U.S. Poet Laureate Rita Dove wrote “The Return of Lieutenant James Reese Europe,” describing Europe’s band “stepping right up white-faced Fifth Avenue in a phalanx.” But Dove’s paean came 85 years later. In 1919, even mainstream—read white—newspapers emphasized Caucasian New York’s adulation for the man. Reporters noted that among onlookers waving flags from windows of their Fifth Avenue homes as the 369th marched past in February were industrialist Henry Frick and society doyenne Mrs. Vincent Astor.

Yachtsman John Wanamaker Jr., grandson of the department store founder, and fellow Manhattan aristocrat Hamilton Fish, about to be elected to Congress, were among those at the May funeral parade. “[O]ne of the most remarkable ever seen in this city,” the New York Sun reported. “The crowd that turned out to see the cortege jammed the sidewalk all along the line of march.” Floral tributes to Europe filled six vehicles. His was the first public funeral procession in New York City for an African American. By the time of his death, James Europe had become a one-man catalog of firsts.

James Europe began counting musical coups as soon as he moved north from his boyhood home in Washington, DC, in 1904 and after high school plunged into performing in New York, redefining African Americans’ role in American music. From a musical family—both parents played instruments—he had had a top-notch musical education, including instruction from the assistant director of the Marine Corps Band. The Europes had come to Washington from Mobile, Alabama, in 1889, when Henry Europe got a job at the headquarters of the U.S. Postal Service. Jim was nine. Enrolling in third grade at Lincoln Grammar School on Capitol Hill, the boy studied violin with Joseph Douglass, a grandson of Frederick Douglass. He went on to learn piano, adding music theory and instrumentation at M Street High. However, violin was his forte—until he arrived in New York to find pianists more needed than violinists.

In music as in comedy, timing is everything, and Europe, by intent and by fortune, had brilliant timing. Demand for black musicians in New York was booming. Besides brothels and gambling dens, Manhattan’s Tenderloin District, emanating from Sixth Avenue and the West 30s, was home to clubs and saloons that drew white patrons to hear black musicians play ragtime. That vigorous genre inspired a vogue for the “Texas Tommy,” the “turkey trot,” and other energetic dances like the foxtrot and one-step.

New York City was also the casting center for black musicals touring nationwide and for vaudeville bills that often included black acts. Europe immediately landed a spot as a cabaret pianist, and within a year was joining a new troupe, the Memphis Students.

The Students, a group of musicians, singers, and dancers, provided Europe with his first first. Organized into a standard ragtime ensemble of banjos, mandolins, and guitars, plus a saxophonist, the Students played Manhattan’s Victoria Theatre at 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue. Their shows proved such a hit that management booked them for a five-month stand. Thanks to that sax, some historians deem that Victoria Theatre residency the first time musicians played jazz on a stage in New York City.

As soon as the Students closed at the Victoria, Europe’s ability as an orchestra conductor and composer began bringing him gigs. By 1907, he was working on Broadway. As music director of The Shoo-Fly Regiment, he had charge of the orchestra and the show’s 40-member chorus. Regiment’s score included “On the Gay Luneta,” a Habanera-flavored number by Europe that became a modest hit.

Before Shoo-Fly Regiment, Broadway and environs had booked no all-black musicals, despite New York’s status as a hub for black performers. The African-American songwriting team of Bob Cole, J. Rosamond Johnson, and Rosamond’s brother James Weldon Johnson, a Harlem poet and civil rights activist, had been writing and plugging songs like “Under the Bamboo Tree” to white producers. White casts’ performances gave the creators a series of veiled successes. Shoo-Fly was the trio’s effort at moving blackness into the footlights. A tale of students at a thinly disguised Tuskegee Institute volunteering to fight in the Spanish-American War, Shoo-Fly wallowed in stereotypes but reflected reality—the hard-fighting exploits of black Buffalo Soldiers in the Philippines and Cuba (“Rough Ride,” February 2018). Road-tested for seven months before hitting Broadway, Shoo-Fly Regiment was “the most ambitious effort yet attempted by a colored company,” wrote the critic for the Topeka Daily Capital in Kansas.

Shoo-Fly Regiment closed on August 17, 1907. Europe scuffled among musical jobs at hotels and cabarets and with black musicals like Mr. Lode of Koal, starring African-American vaudevillian Bert Williams. However, pricier venues kept black musicians generally at bay. When a house did hire African-American performers, management paid them less than white musicians, sometimes on the assumption that blacks, while skilled ear players, were not able to read sheet music.

To end-run racial barriers, Europe adopted a business persona—part union organizer, part booking agent, part impresario. He formed the Clef Club, crediting the best musicians he could find. They performed as an orchestra, in smaller ensembles, and on assignment to other groups. In another Europe first, his Clef Club broke ground by placing black musicians with prestigious white orchestras, guaranteeing their professionalism and holding clients to fair contracts and decent wages. The cream of his musicians made up the 100-member Clef Club Orchestra, which debuted spectacularly in May 1910 at Harlem’s Manhattan Casino. “Between five and six thousand persons were present,” the Washington Bee reported. “It was certainly the largest gathering of colored people New York has ever witnessed.” To end the program the group performed a rousing Europe composition, “Clef Club March.” The Clef Club began appearing around New York, performing light classics but always closing with “Clef Club March.”

The orchestra returned to Manhattan Casino in 1911, drawing listeners from as far away as Boston, Baltimore, and Washington for what a newspaper called “the crowning social and musical function of the season.” The concert—an amalgam of orchestral numbers, solo vocals, and dancing both tap and balletic, began at 8:15 p.m. At 11 p.m., the Clef Club Orchestra stood down. Once the hall was cleared of chairs, concertgoers danced until 4 a.m. to the Thomas Colored Orchestra of New York. On the strength of rave reviews for those and other shows, Europe on May 2, 1912, brought his very big band to Carnegie Hall for a program featuring works by African-American composers.

For its debut at the nation’s most prestigious music venue, the Clef Club Orchestra swelled to 125 members, arranged around an 85-piece plectrum section of mandolins, bandores, guitars, and banjos. Imbuing the feel of a symphony orchestra with a black cadence, Europe was intent on letting the musical world know that black musicians’ heritage, while different, was no less worthy than mainstream standards for “classical” music in place since the 1800s.

“We have developed a kind of symphony music that, no matter what else you think, is different and distinctive, and that lends itself to the playing of the peculiar compositions of our race,” Europe said. “Although we have first violins, the place of second violins with us is taken by mandolins and banjos. This gives that peculiar strumming accompaniment to our music. Then for the background we employ 10 pianos. The result is a background of chords which are essentially typical of Negro harmony. Other peculiarities are our use of two clarinets instead of an oboe. As a substitute for the French horn we use two baritone horns, and in place of the bassoon we employ the trombone.”

At Manhattan Casino, Clef Club’s audiences had been black. The Carnegie Hall crowd knew no color line; blacks and whites snapped up tickets, and, as University of California professor emeritus Olly Wilson wrote afterward, “Carnegie Hall obviously rocked that evening.” With this show, Europe “stormed the bastion of the white musical establishment and made many members of New York’s cultural elite aware of Negro music for the first time,” composer Gunther Schuller wrote 60 years later.

“That first concert of Negro music in Carnegie Hall was an ear-opener,” wrote ethnomusicologist Natalie Curtis-Burlin, who attended. “The dance craze was then sweeping the city, and the Negro players were feverishly demanded. The sun shone, the colored musicians became professionals.”

Most Clef Club players had been toggling between playing and holding straight jobs. The Carnegie set opened doors to full-time musicianship. Europe and cohort began making a living wage, advancing from triumph to triumph. “Jim Europe was the living open sesame to the colored porters of this city,” said Fred Johnson, later to lead the Clef Club. “He took them from their porter’s places and raised them to positions of importance as real musicians.”

Europe and his Clef Club Orchestra, now darlings of Manhattan’s upper crust, returned to Carnegie Hall in 1913 and 1914. The bandleader also had multiple ensembles working a society ball circuit whose rounds he made nightly. “Our Negro orchestras have nearly cleared the field,” Europe bragged to the New York Herald in 1913. In one week that August his schedule included a dance hosted by a Vanderbilt and another put on by an Astor. In 1915, Europe’s orchestras had revenues of $100,000—today, nearly $2.4 million.

Black musicians and black music had become chic with white socialites, but racism persisted, underlain by musical jealousy. “In this occupation, as in all other desirable ones here in America, the Negro’s color is a handicap, and wherever he achieves success he does so in the face of doubly severe competition,” Europe told the New York Evening Sun. However, white players had trouble with ragtime’s backbeat tempo and syncopation; they just could not swing. In contrast, “music rendered by a Negro orchestra rarely has the mechanical quality which is fatal to dancing,” Europe said. “The Negro has a superior sense of rhythm, peculiarly adapting him for dance music. The art of playing the modern syncopated music to him is a natural gift.”

Europe’s and his sidemen’s gifts brought another first. White dancers Vernon and Irene Castle were the country’s most popular hoofers. The married couple’s innovation had been to junk the formality of Gilded Age ballroom dance, substituting elegant athleticism, precise but exuberant. They performed and taught styles absorbed from the cabaret scene, like the foxtrot, and displayed daring beyond the dance floor.

In 1913, the Castles began performing with Europe and an 11-piece band they had had him recruit backing them on numbers like Europe’s composition “Castle House Rag.” In touring with a black orchestra, the Castles might as well have been detonating a cultural bomb. They knew exactly what they were doing.

“The colored bands jazz a tune,” Irene Castle said. “That is to say, they slur the notes, they syncopate, and each instrument puts in a world of little fancy bits of its own.” The Castles, who fostered the foxtrot into a craze and then a standby, credited Europe with introducing them to what he called an “essentially Negro dance.”

Between tours with the Castles, Europe and band signed with the Victor label. At sessions in December 1913 and February 1914 in the Victor studios at 234 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, the group recorded “Castle House Rag” and seven other tunes from their sets with the Castles; that October the band laid down two more sides. Previously, Victor’s only black artists had been the Jubilee Quartet, specializing in proper renditions of spirituals. Europe’s Victor sessions reveled in a profoundly black sense of rhythm. “Castle House Rag,” while not quite jazz, came closer than any other mainstream recording. The dense melody, performed with muscular vigor, clocked in at a propulsive 118 beats per minute. The 78-rpm disc ranked 10 in sales for 1914; Victor pressed copies until 1920. Europe did not go into the studio again until 1919, when he did so as an international star and a veteran of World War I.

The Great War wrote the James Reese Europe story’s most illustrious chapter. But for the war, he might have been a hit in his namesake continent much earlier—he and his orchestra had a Continental tour with the Castles scheduled until the fighting began on July 28, 1914. Instead, Europe dove into club and private party bookings. In September 1916, he and fellow performer and songwriter Noble Sissle joined the 15th New York Regiment, a unit of the National Guard in Harlem and a real-world variant on the theme of The Shoo-Fly Regiment. New York Governor Charles S. Whitmore had formed the unit at the suggestion of Charles W. Fillmore, a veteran of Spanish-American War service as a Buffalo Soldier. Fillmore served as senior captain under Commander William Hayward, a Caucasian. When Europe, who saw a Harlem-based Guard unit as a step toward equality for African Americans, passed the examination for a commission, he was made a second lieutenant.

Europe was assigned to command the regiment’s machine gun company. Hayward asked him to organize a regimental band, even inveigling funding to pay players Europe recruited. In April 1917, the United States entered the war. That winter, the regiment, mobilized as the 369th U.S. Infantry, sailed to France—though, courtesy of U.S. Army racism, it was cut out of a farewell parade given other New York units. The 369th landed at Brest on December 27. Seconded to the French Army because the American Expeditionary Forces refused to field a black unit, the men of Harlem fought fiercely at Belleau Wood and in the Second Battle of the Marne. They were in combat for 191 days, longer than any AEF unit, earning the nickname “Harlem Hellfighters.” The first French Croix de Guerre medals for valor awarded Americans went to Hellfighters.

When the 369th reached the front, Europe trained his men how to use the French Chauchat machine gun and throw hand grenades. He was the first black American officer to lead soldiers into combat; with Europe in command, the 369th conducted raids into no man’s land until poison gas struck down Europe.

After several weeks’ recuperation, Europe recovered sufficiently to be able to lead the Hellfighters band at performances for American and French troops and French civilians—a wildly successful morale boost, “filling France full of jazz,” Sissle said. Ordered to Paris in conjunction with an Allied conference to play the Théâtre des Champ-Elysées, the band was such a sensation that its theatrical booking stretched to eight weeks.

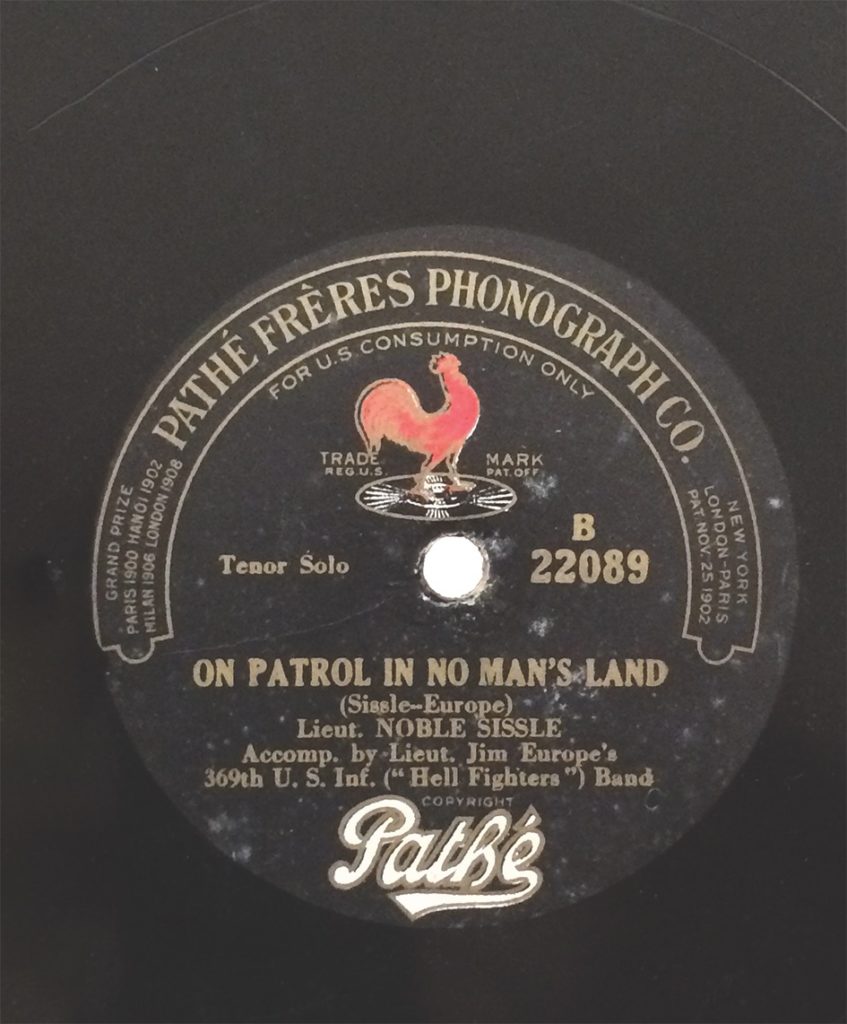

Europe’s music attracted French label Pathé, which arranged for recording sessions to take place in America when the musicians mustered out. The Hellfighters were the first New York unit to sail home. Hayward pushed hard to prevent a repeat of the insult that had marked their departure for combat. His insistence won his men a parade that saw the Hellfighters march on February 17 from Washington Square in Greenwich Village to Fifth Avenue and 142nd Street in Harlem. The regiment demobilized on February 28, 1919. Now civilians, band members were to tour nationally as the Jazz Military Band. In March, the men cut 18 sides for Pathé, hit the road, and returned on May 7 to the New York City studio to cut six more tunes. Pathé advertised the recordings as the work of “the world’s greatest exponent of syncopation”—James Europe.

Swinging harder and more freely than the 1914 Victor recordings had, the Pathé sides were unequivocally jazz—some reflecting life during wartime. “On Patrol in No Man’s Land” includes the lyric, “Drop! There’s a rocket from the Boche barrage/Down, hug the ground, close as you can, don’t stand, creep and crawl.”

The Pathé 78s and the Jazz Military Band’s 1919 national tour, with Sissle singing lead, had a synergistic effect. These one-night stands had audiences and critics alike raving about the group’s blend of military marches and black jazz. “The whole program magnificently expresses the devil-may-care spirit of the American army and the elemental glee of the colored race,” wrote the reviewer for the Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger. “We won France playing music which was ours and not a pale imitation of others, and if we are to develop in America we must develop along our own lines,” Europe said.

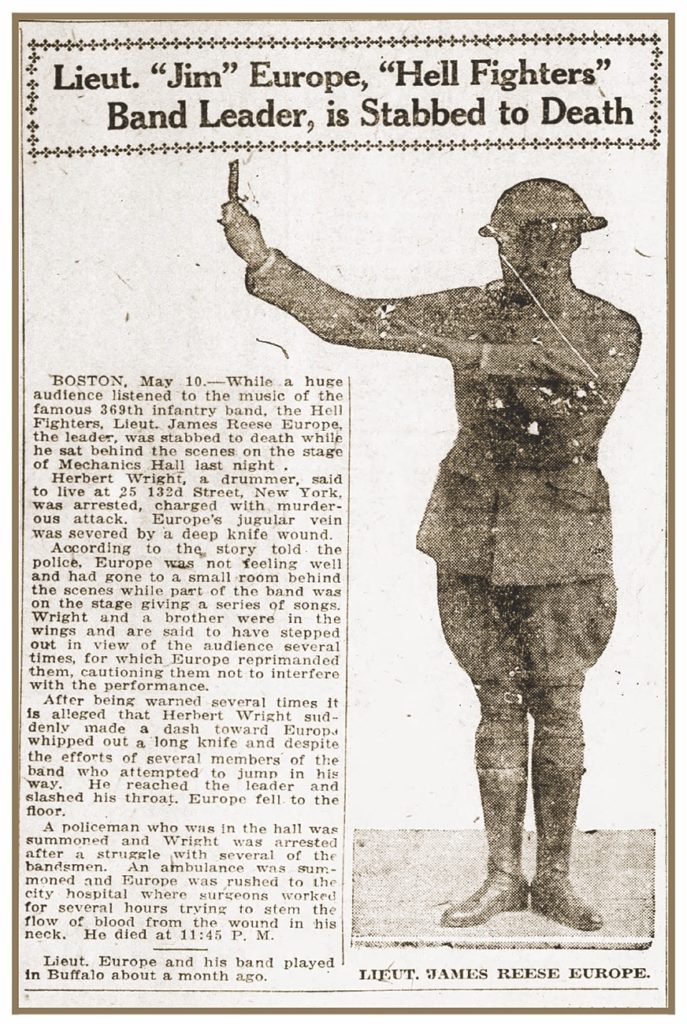

In Boston, the promoter had booked the Jazz Military Band at Mechanics Hall beginning May 9. During the first show, drummers and brothers Steve and Herbert Wright, billed as the “Percussion Twins,” annoyed their boss by giggling and wandering offstage during numbers. At intermission, the bandleader upbraided the percussionists. An angry Herbert Wright lunged at Europe with a penknife, striking him in the neck. The wound seemed minor.

Before leaving to be treated at Boston City Hospital, Europe insisted the band go back on. Wright’s blade had severed an artery. Doctor could not stanch the bleeding. Europe died early on May 10, 11 weeks after his 39th birthday.

James Europe returned to Harlem in a coffin to a cavalcade of mourning. Buffalo Soldier and fellow Hellfighter Chester Fillmore was one of his pallbearers.

The New York Clipper wrote, “He was only a black man, was Jim, but they laid him away as though he had belonged to a more fortunate race.” On May 13, three separate services took place. “Early in the morning Negroes marched in hundreds into the funeral parlor on West 131st Street, where the famous Negro entertainer then lay,” the Sun reported of a wake that included a Masonic service. “They packed the adjacent streets.”

James Reese Europe’s final first was that parade to St. Mark’s African Methodist Episcopal Church on West 53rd Street, an unprecedented honor for a black man. The musicians who had played with him in the Hellfighters band marched in silence, but a new ensemble organized by the reconstituted regiment did play. After a service at St. Mark’s, a military escort and long cortege followed the coffin to Pennsylvania Station for transport to Washington, DC, and interment at Arlington National Cemetery.

In subsequent decades, African-American performers deployed their will and their skill to resist oppression, as Europe had, meanwhile remaking popular music and culture. Europe and other pioneers of self-expression made as much difference in American life as they did on the American stage, setting the stage for the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century.

Noble Sissle’s songwriting partner, Eubie Blake, who lived through and participated in much of that struggle, called Europe “the Martin Luther King of music.” As part of a 1989 Landmarks of Jazz series, a modern simulacrum of the Clef Club Orchestra recreated the original 1912 set on the Carnegie Hall stage. In 2004 the Library of Congress, adding “Castle House Rag” to the National Recording Registry, called the tune “electrifying.” Library historians recognize no true jazz recordings released until three years after the Victor “Castle House Rag.”

This article was written in American History Magazine. For more, subscribe here.