Some American wars have begun with a bang—World War II—others only after long wrangling: the Gulf and Iraq wars.

And some never began, though every ingredient, from latent hostility to bad behavior, was in place. The Lincoln administration, consumed though it was by its death struggle with the Confederacy, nearly took on Britain at the same time. How did the guns not go off?

Bad blood between Britain and America was a living memory in 1861: Winfield Scott, the U.S. Army’s 74-year-old commanding general, started soldiering in the War of 1812.

Britain, proud for having ended slavery in its empire in 1833, might have been expected to back the Union. Sympathy for the underdog, upper-class regard for the hierarchical South, and the need for cotton to feed the textile trade tugged at many Britons.

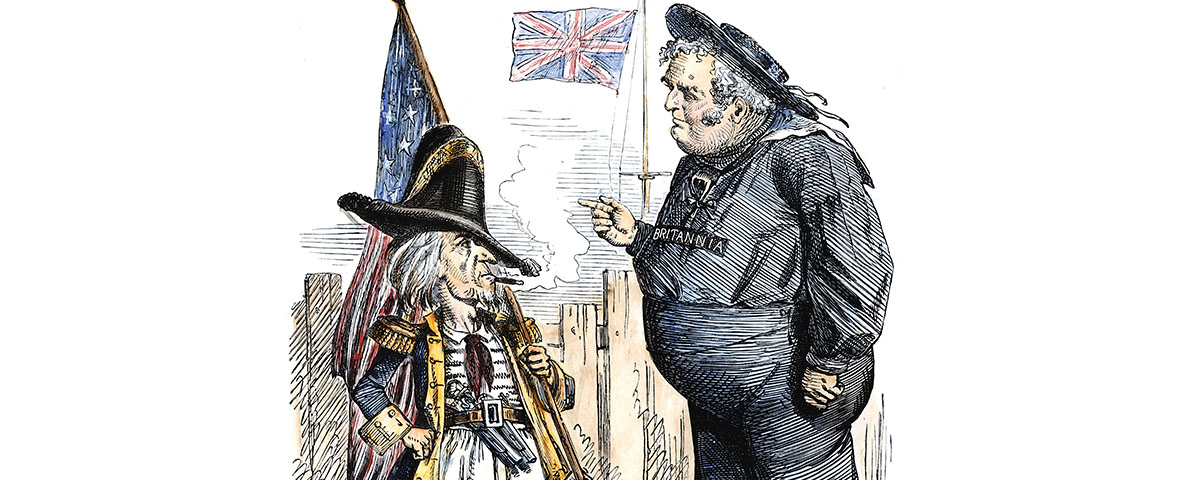

Bellicose personalities held positions of power in both Washington and London.

William Seward, Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state, was an expansionist who would buy Alaska and Midway Island and bid on the Danish West Indies. Any would-be imperialist automatically was bound to collide with the Brits, masters of that game. As New York’s governor, Seward had cultivated Irish immigrants; would his friends’ foe be his foe? An assertive and presidentially minded fellow, Seward quickly came to respect and even love Lincoln, but his take-charge habits persisted.

Britain’s Prime Minister Henry Temple, the Viscount Palmerston, was, if anything, more brash. His sharp elbows and occasional blunders moved foreign countries, the House of Lords, and Queen Victoria herself to complain. Henry Adams, son of Lincoln’s minister to Britain, Charles Francis Adams, wrote that Palmerston “could no more resist scoring a point in diplomacy than in whist.”

Seward struck first, on April 1, 1861, before Fort Sumter fell. In a memo blandly headed, “Some thoughts for the President’s consideration,” Seward proposed to solidify the Union by picking quarrels with Spain, France, Russia, and Britain, “to rouse a vigorous continental spirit of independence.” Lincoln nixed that scheme. In May, Seward floated another. Britain had declared neutrality, allowing Confederate vessels to resupply—but not arm—at British ports. Seward wanted Charles Francis Adams to warn the Foreign Office that if Britain meddled in American affairs “we shall cease to be friends and become once more, as we have twice before been forced to be, enemies…” Lincoln revised Seward’s note before sending a version to Adams, who dialed down the language more in delivering the message.

An incident at sea gave the two countries something to quarrel about. In November 1861 the frigate USS San Jacinto, cruising in the Bahama Channel, stopped a British mail boat, the Trent, with Confederate diplomats James Mason and John Slidell aboard. Union sailors seized the men, carrying them to Boston Harbor to be imprisoned. This unfriendly act dumbfounded Britain—nations at peace do not wantonly board each other’s ships—and Palmerston wrote a sharp note meant for Seward. To that draft Prince Albert, Victoria’s husband, dying of typhoid, added language hinting that the seizure had not been official policy. Lincoln and Seward took the proffered out. In January 1862 the two Confederates were put aboard a second British mail ship.

Palmerston’s chance to goad came in May 1862. In New Orleans, which the Union had taken, a woman emptied a chamber pot onto U.S. Navy Flag Officer David Farragut. Major General Benjamin Butler, the Crescent City’s military governor, ordered that ladies insulting Union troops be deemed women “of the town,” or whores. Palmerston sent a note voicing “disgust” to Adams, who deflected the PM by asking if his letter had been official or personal, then insisting they communicate via British foreign secretary Earl Russell.

Britain’s least friendly act was allowing the Confederacy to order British-made warships. In May 1862, John Laird Sons & Co. of Birkenhead launched a sloop that, once armed in the Azores, was christened the CSS Alabama. For two years Alabama preyed on Union shipping. To Union protests, the British government responded that since the vessel had been armed after it sailed, Britain had no legal responsibility for its actions. Next in the Laird production line were two ironclads fitted with prows with which to ram U.S. Navy ships blockading Southern ports. The rams, ostensibly commissioned by the khedive of Egypt, were to be named North Carolina and Mississippi upon delivery to their actual purchasers.

In September 1863, Adams declared in a note to Russell that the rams were meant to wage “war against the United States”—a clear violation of neutrality. The note from Adams crossed one from Russell explaining that the Egyptian cover story barred him from interfering with the rams’ completion or delivery. Adams, in a second note, composed one of the mildest, most menacing sentences in American diplomacy: “It would be superfluous in me to point out to your lordship that this is war.”

Adams neither blustered nor quibbled about what Russell and his government were permitting; he simply noted the consequences—a Yankee foreshadowing of Michael Corleone’s “You’re nothing to me now.”

Before Adams sent that second note, Russell and Palmerston decided to buy the rams for the Royal Navy, defusing the crisis. Why back down? The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, had unified British liberals behind the Union; workingmen of Manchester sent Lincoln an address looking forward to “the victory of the free north.” In July, the free North won major victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Britain saw no percentage in risking neutrality violations for a lost cause. In 1864, the USS Kearsarge sank the Alabama; Britain ultimately paid the United States $15.5 million in damages for claims against Alabama’s depredations. After Lincoln’s assassination, the Earl Russell led the House of Lords in a unanimous vote of “sorrow and indignation…at that atrocious deed.”

Can America and North Korea achieve similar amity against the backdrop of a much darker past? The Korean War (aka Conflict) ended in armistice, not a peace treaty.

Since then North Korea’s provocations have ranged from seizing the USS Pueblo in 1968 to axe-murdering two American soldiers in the DMZ in 1974. Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama tried to engage North Korea in agreements limiting its nuclear program to peaceful uses, only to face lies and tests of atomic bombs and intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Rhetoric has gone way beyond Seward’s and Palmerston’s prose. In a September speech to the United Nations General Assembly, President Donald Trump called Chairman Kim Jong Un “Rocket Man…on a suicide mission for himself and for his regime.” Kim called Trump a “mentally deranged U.S. dotard.”

The great difference between the two situations is that 19th-century America and Britain were civilized states; modern North Korea is a family dictatorship, simultaneously feudal and communist, bent on becoming a world power.

With skill and luck, wars sometimes do not happen. Fingers crossed.