Shohei Ooka was drafted into the Imperial Japanese army shortly after New Year’s Day in 1944. The 35-year-old Ooka was an unlikely soldier. A professional literary critic fluent in French and English, he loved European culture and considered himself a disciple of French philosopher Stendhal, famed for his romanticism and liberal principles.

A husband and father of two young children, Ooka resented being drafted to fight in the war. Scribbling a caption on a February 1944 photo of himself in uniform, Ooka wrote: “Second Class Private—and not very happy about it. I must try to keep my hatred for the military from turning into a hatred for humankind.”

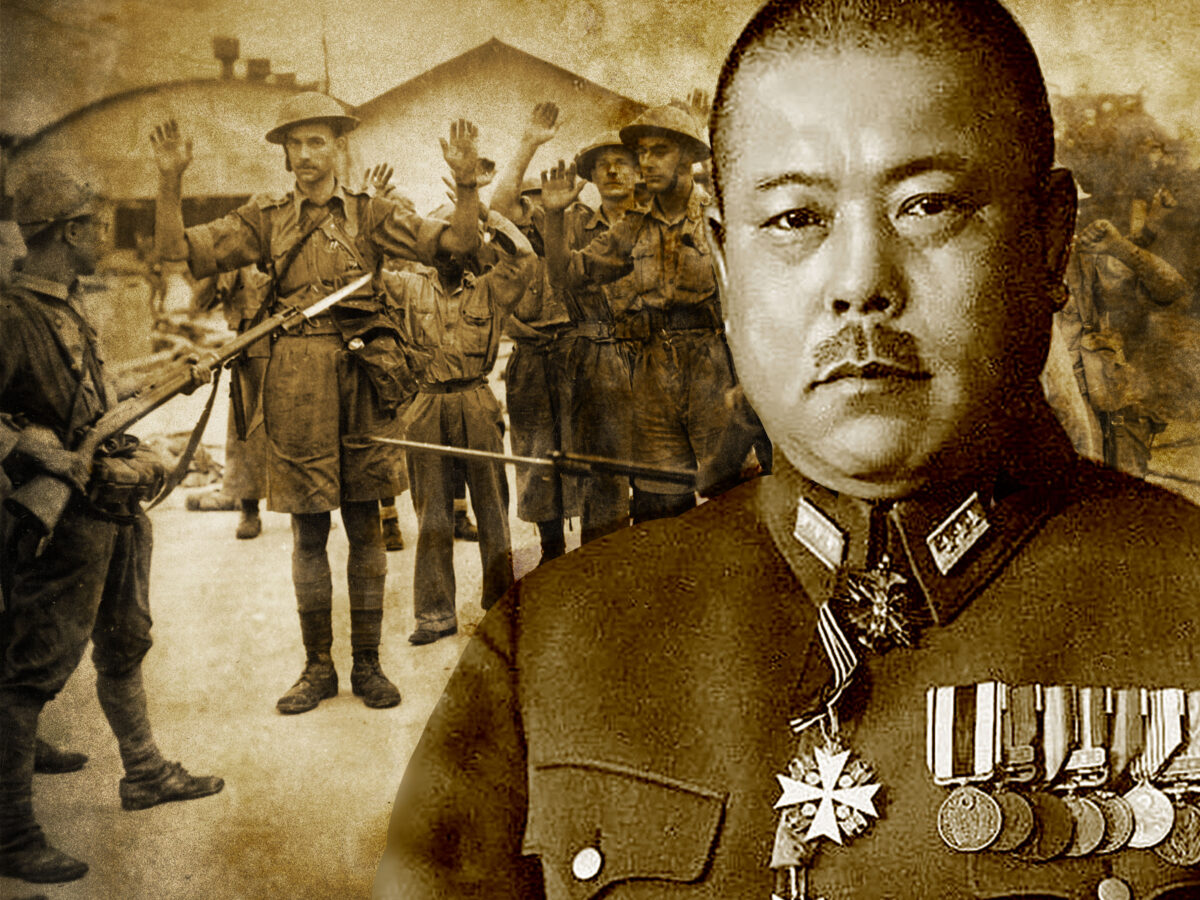

After reporting to a depot in Tokyo and receiving several weeks of poor training, he was packed off with a newly formed infantry battalion to the Philippines to help stave off the impending American landing on Mindoro. Two U.S. regimental combat teams landed there on Dec. 15, 1944 to pave the way for an assault on Luzon, facing less than 1,000 Japanese troops effectively abandoned by Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita.

Wandering in the jungle, the Japanese prowled for food and succumbed to malaria as they sought to hide from American forces. Ooka and his comrades camped in the mountains for 40 days “until an attack by American forces on January 24 sent us scattering in every direction,” he wrote.

Driven to the edge of his sanity, Ooka attempted to hide in the jungles but was captured on Jan. 25, 1945. He spent the duration of the war in an American POW camp on Leyte. Repatriated to Japan at the end of 1945, Ooka became a writer and worked as a lecturer on French literature at Tokyo’s Meiji University.

Ooka was haunted for the rest of his life by the war, which he documented in his autobiographical 1948 book Taken Captive. His 1951 war novel Fires on the Plain, based on his and other POWs’ gruesome experiences, was later adapted into an award-winning 1959 film.

The following excerpt is Ooka’s account of his failed suicide attempts and capture by American forces from an English edition of Taken Captive, translated and edited by Wayne P. Lammers. Recurring themes in the book are Ooka’s feelings of guilt about comrades who died, his failure to understand his own behavior in brutal circumstances and his decision to stop fighting. The book opens with a quote from Tannisho, a 13th century Japanese Buddhist treatise, which reads: “It is not from goodness of heart that you do not kill.”

His firsthand account begins here.

“Failed To Explode”

My life today owes itself to the accident that the hand grenade I carried was a dud. Of course, since they say that 60 percent of the hand grenades issued to Japanese troops in the Pacific were duds, my good fortune cannot be considered an especially rare stroke of luck.

The relative ease with which I was able to cross over the line that should have marked the end of my life probably owed to my physical infirmity at the time.

In my mind I tried to picture the faces of all those I had loved, but I could not bring any of their images into focus with the clarity of a picture. Feeling a little sorry for them as they milled vaguely about in the depths of my consciousness, I smiled, said, “So long,” and struck the head of the fuze against a nearby rock. The fuze assembly flew off, but the grenade failed to explode.

I examined the grenade minus its fuze. A hole ran down from the middle of the grenade from its now exposed top, and at the bottom of this hole was a small round protuberance—obviously the detonator. I looked at it and shuddered. This was the only time during my day and night alone in the woods that I consciously experienced genuine terror.

I gathered up the pieces of the fuze assembly and put them back together. The slender rod that fit down into the hole appeared too short to reach the detonator inside. I struck the assembly against the rock again, but the grenade remained intact.

“The Irony of Fate”

I had to smile. The irony of fate that refused to grant me even a quick and easy death seemed funny to me somehow. Everything that had befallen me in the last twenty-four hours had been altogether one great irony. I clicked my tongue in irritation and hurled the grenade deep in the forest…

Recommended for you

I next attempted to kill myself with my rifle. Sitting up, I removed my right boot and then held the barrel to my forehead with both hands as I tried to push the trigger with my big toe. (I had learned this arrangement from the veterans during basic training in Japan.) To my chagrin, I immediately lost my balance and rolled over onto my side. I’m sure to botch it up this way, I thought. Recalling a story I had read about a man who shot himself twice in the mouth but succeeded only in blowing away his cheek, I decided it would be wiser to wait until my fever subsided at least a little.

In this case, too, if I had been more determined, I would surely have thought to push the trigger with a stick…Instead, I behaved like a man who only halfheartedly wished to kill himself. At the same time, I must ultimately consider myself fortunate that the rifle barrel in my hands moved away from my forehead when I lost my balance and fell over, thus preventing me from realizing that I could in fact shoot myself in that position.

I laid the rifle down beside me. Instead of putting my right boot back on, I took off my left boot as well and lay down again. I seem to remember the sun having climbed quite high into the sky by this time. I had apparently been contemplating and going through the motions of my suicide in an extremely dilatory fashion. My thirst must have remained, but I have no recollection of it.

Decision to Surrender

I do not know whether I dozed off or passed out, but the next thing I remember is gradually becoming aware of a blunt object striking my body over and over. Just as I realized it was a boot kicking me in the side, I felt my arm being grabbed roughly, and I returned to full consciousness.

One GI had hold of my right arm, and another had his rifle pointed at me, nearly touching me. “Don’t move. We’re taking you prisoner,” the one with the rifle said.

I stared at him and he stared at me. A moment passed. I saw that he understood I had no intention of resisting.

Later, at the POW camps, the Americans often asked me: “Did you give yourself up, or were you taken prisoner?” No doubt they wanted to see if it was true that we Japanese would kill ourselves rather than give ourselves up.

I made a point of answering proudly, “I was taken prisoner.”

“Do you think we killed our prisoners?” they asked next.

“I’m not fool enough to believe that kind of propaganda,” I answered.

“Then why didn’t you give yourself up?”

“It’s a question of honor. I have nothing against surrendering as such, but my own sense of pride would not let me submit voluntarily to the enemy.”

Now that I am no longer a prisoner trying desperately to hold onto my self-respect, I can take a different view of the event. Since I gave up all resistance quite willingly when faced with that rifle, I can admit that I did, after all, give myself up. The difference between surrendering to the enemy with a white flag raised and casting down one’s arms when surrounded is merely a matter of degree.

The first GI gathered up my rifle and sword while the second kept his weapon trained on me. “Get up and start walking,” he said.

“I can’t walk.”

“Walk, walk,” they both repeated.

Taken to The American Camp

We went down the path I had come up the day before. I stumbled from one tree to the next as far as the dry streambed and then sank to my knees with nothing to hold onto. One of the GIs put his arm through mine to help me along.

Noticing the canteen at his waist, I said, “Water?”

He shook his canteen to show me it was empty and said, “No.” He turned to look at his companion.

“No,” he said.

We reached the clearing of the day before, where I had first descended into this canyon. Helmets, a mess kit, a pot of half-cooked rice, a crushed gas mask and sundry other items lay strewn about. I saw no blood, but I did not doubt that many men from my unit had died there. One of the sergeants had been carefully ripening some bananas. Seeing them scattered on the ground made my heart weep.

The climb to our former command post was arduous. As we neared the hut, the GI who was helping me walk shouted continually, “Don’t shoot. Don’t shoot.”

At the hut, they turned me over to four or five other GIs, who checked me carefully for hidden weapons. I was then escorted along the ridgeline to a plateau cultivated by the Mangyans [indigenous people of Mindoro island, Philippines]. A force of some five hundred Americans had set up camp there…

The Diary of the Dead

The interrogation must have taken at least an hour. The commander repeated certain important questions several times. Trying to be sure I gave the same answer every time made me tense. The effort exhausted me.

The commander took out a Japanese soldier’s diary and told me to translate what it said. I welcomed this respite from the barrage of questions and set about translating the diary line by line. It was written in a childish hand, and the opening entry was from when our company had been stationed in San Jose [city in eastern Mindoro]. The author declared he had stopped keeping a diary after joining the army, but since he could not find anything else to do for diversion, he had decided that setting things down in a diary when off duty would in no way compromise the discharge of his responsibilities…The entry went on and on in this jejune vein—words placed there in case the diary fell into the hands of his superior officer, no doubt. That was all, however. There were no further entries.

The author had not inscribed his name, and I did not recognize the hand, but I knew it had to have belonged to one of our young reservists from the class of 1943. Though these greenhorns had proved themselves to be utterly ignorant of anything, they were also kind and generous and worked hard to cover for the cunning and indolence of us older men. They knew nothing about pacing themselves to conserve their strength, so when they fell ill they were quick to die.

I looked up from the diary. The commander was looking at me with eyes that seemed to hold both sympathy and familiarity. We spoke at the same moment.

“That’s all.”

“That’s enough.”

This brought my interrogation to an end.

The commander turned sideways and said in a low murmur, “We’ll get you something to eat, now. Someday you’ll be able to go home.” I lay there vacantly, my spirit too tired to respond.

One of the soldiers returned the papers to the haversack. The owner’s name stitched on the flap flashed before my eyes. It had belonged to “K,” the son of the rakugo [a type of Japanese solo stage performance] critic, the fellow who had protested “Aren’t we going together?” when we were preparing to evacuate the squad hut and I decided I would get a head start.

My shock was immense. I turned my face away and screamed, “Kill me! Shoot me now! How can I alone go on living when all my buddies have died?”

“Be glad to,” I heard someone say. I turned toward the voice to find a man leveling his automatic rifle at me. “Go ahead,” I said, spreading my chest, but my face twisted into a frown when I saw the playful gleam in his eye. The commander walked away as though he had never even heard my cries.

Sick with Malaria

A package of cookies fell on my chest. I looked up to see a ruddy young soldier with a dark stubble of a beard standing over me. His face was blank. When I thanked him, he silently shifted the rifle on his shoulder and walked away.

I resumed my observation of the American troops around me. Never before had I seen men of such varied skin tones and hair color gathered together in a single place. Most of them seemed to be off duty—though a few had work to do. A man with a mobile radio unit on his back stopped near me with the entire sky spread out behind him. He adjusted something and then moved on. One group of men was taking turns peering through what looked like a surveyor’s telescope on a tripod.

Far away in the direction of the telescope pointed rose a range of green mountains. Somewhere among those mountains was the ridge over San Jose where our detached platoon was camped. I gazed off at the distant range, caressing each beautiful peak, each gentle mountain fold with my eyes. The platoon could be under attack even now, I thought. I mentally reviewed everything I had said during my interrogation, trying to reassure myself I had said nothing that could be harmful to them.

A burly, middle-aged soldier approached and took my pictures. Coming closer he said, “What’re you sick with?”

“Malaria,” I answered.

He felt my forehead with his hand. “Open your mouth,” he commanded. When I obeyed, he tossed in five or six yellow pills and said, “Now take a drink.” After watching me wash the pills down he explained, “I’m the doctor,” then walked off.

To an Unexpected Future

Flames rose from the hut that had housed our command post, as well as from the squad hut with the sick soldiers where I had first rested the day before. I had never seen columns of flame rise so high. Perhaps the huts had been doused with gasoline to help burn the corpses of the dead.

Evening approached. The American troops built fires in the holes I had thought looked like graves and started preparing dinner. An amiable-looking youth brought me some food. I had no appetite. I merely nibbled at a cookie…Except for being awakened several times during the night to take more pills, I slept soundly.

The next morning the commander said, “Today we return to San Jose. The troops will board ship directly south of here, but you will go from Bulalacao [a city on the southeast coast of Mindoro, opposite San Jose on Mindoro’s southwestern coast]. Can you walk?”

“I’ll do my best.”

With GIs supporting me on either side, I managed to stay on my feet all the way down the mountain. Several Filipinos carried me by stretcher from there to Bulalacao, ten kilometers away. Once they had hoisted the stretcher onto their shoulders, all I could see from where I lay was the bright sky and the leafy treetops lining both sides of the road. Watching the beautiful green foliage flow by me on and on as the stretcher moved forward, it finally began to sink in that I had been saved—that the duration of my life now extended indefinitely into the future. It struck me, too, just how bizarre an existence I had been leading, facing death at every turn.