With their loyalty to the U.S. in question, Japanese American soldiers wielded the native language of their parents to save American lives and shorten the Pacific War

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n a ridgetop near Nhpum Ga, Burma, the stench of animals rotting in the oppressive jungle heat was so strong, soldiers of the second battalion, 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) dubbed the place “Maggot Hill.” Stranded there as their provisions, ammunition, and hope dwindled, most of the men masked their terror with foxhole-talk of the girls and families waiting for them back home. But Sergeant Roy Matsumoto kept silent, one ear tuned to his fellow Americans, the other to the familiar rhythms of muffled enemy voices rising from the entrenchments at the base of the hill.

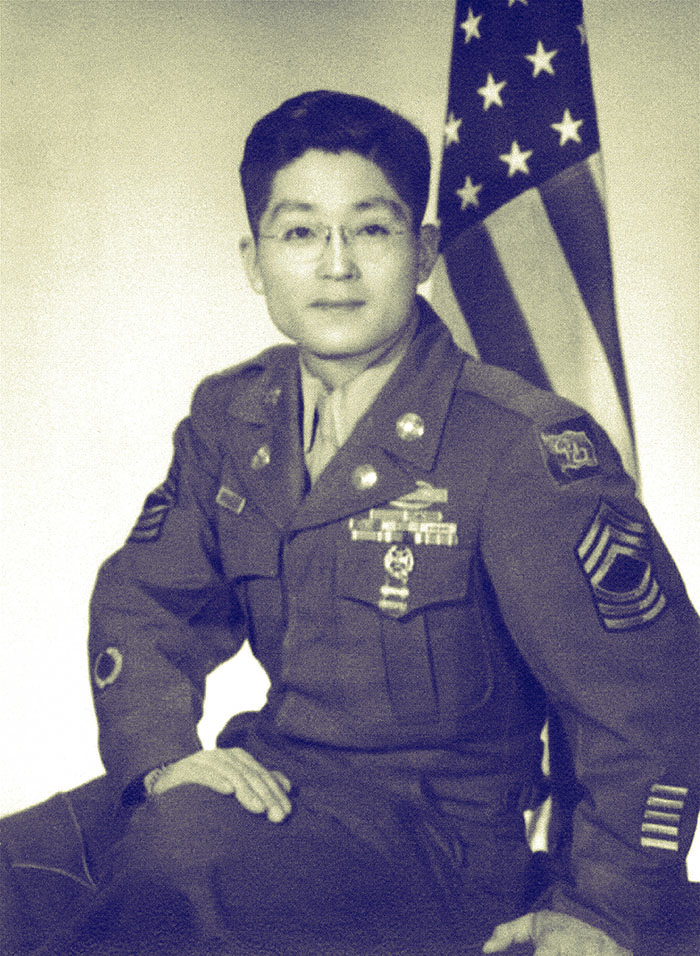

It was April 1944, nearly 14 years since the short, bespectacled sergeant had last seen his parents. Matsumoto, 30, had been born in Los Angeles in May 1913, the eldest son of first-generation Japanese immigrants. At age 8, his parents had sent him to their native Hiroshima to be brought up in Japan’s rigorous school system. The rest of the family soon followed, but when Matsumoto became too friendly with a girl at 17, his parents sent him back to California to finish his education and work in a family friend’s Japanese grocery store. In parting, his mother told him to always remain true to his country of birth.

In spring 1942 that loyalty was tested when Matsumoto and 120,000 other Americans of Japanese descent living on the West Coast were confined to inland internment camps. The outbreak of war with Japan had made their ethnic ties and understanding of the Japanese language subject to mistrust by the U.S. government. Yet those were the very characteristics that led the army to recruit Matsumoto for its top-secret Military Intelligence Service (MIS). Throughout the war, more than 6,000 Japanese Americans would serve in the MIS as translators and interrogators—often at great risk—for 130 units across the Pacific, including the famed Merrill’s Marauders of the 5307th, a precursor to today’s Army Rangers. (See “Conversation with Sam Wilson.”)

In February 1944 Matsumoto and 13 other Japanese American linguists followed Brigadier General Frank Merrill into northern Burma. The linguists’ mission was to interpret captured documents and interrogate prisoners as the 5307th fought against the Japanese 18th Division to retake the Burma Road, a critical Allied supply line connecting Burmese seaports to southwest China. Two months in, Matsumoto found himself isolated with the second battalion at Nhpum Ga, desperate for intelligence that might end the Japanese siege. As had become his nightly custom, Matsumoto shed his jingling pistol belt and helmet and crawled silently to within 15 muddy yards of the Japanese camp, close enough to make out the enemy chatter. His risky exploits paid off just before midnight, when an officer speaking a dialect Matsumoto had picked up during his grocery store days briefed his men for a predawn assault on Maggot Hill.

Matsumoto reported his news to the American lieutenant in charge of the targeted platoon, and the ready Marauders annihilated the first enemy wave to charge the hill at 4 a.m. Stunned by the counterattack, a second wave of Japanese soldiers following close behind began to retreat in the breaking darkness. But Matsumoto leapt from his foxhole, stood between the two lines of fire and—in his best impression of a Japanese commander—shouted “Totsugeki! Susume!” ordering the enemy to advance. The ruse worked; the remaining soldiers rushed straight into an American ambush. Matsumoto’s actions would add another accolade to the trove Japanese American MIS soldiers would earn in a decade of exemplary service to a nation that had questioned their allegiance.

IN SPRING 1941, as Japan’s actions in the Pacific made war with the U.S. increasingly likely, U.S. Army intelligence officers Major John Weckerling and Captain Kai Rasmussen predicted the need for skilled linguists to support military operations abroad. Granted a $2,000 budget by the War Department to open the Fourth Army Intelligence School, under the Western Defense Command, Weckerling and Rasmussen began recruiting soldiers with an aptitude for the complex Japanese language.

The best candidates were Nisei, American-born progeny of parents who had come to the United States from Japan before immigration was banned in 1924. Most Nisei had a working knowledge of spoken Japanese and exposure to its writing system known as kanji, which gave them an edge in tackling the school’s accelerated curriculum. Weckerling and Rasmussen interviewed hundreds of Nisei soldiers and selected 58 of the most advanced linguists to begin lessons in an abandoned air hangar at the Fourth Army headquarters at the Presidio of San Francisco in November 1941. After the attack on Pearl Harbor raised skepticism of Japanese American loyalty, they added about a dozen white recruits to the class roster, hoping to cultivate them into officers who could lead the Nisei in the field.

Using photocopies of Japanese military handbooks Rasmussen had picked up as an attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo, and Japanese dictionaries purchased from bookstores in San Francisco, instructors coached students through intensive study of Japanese military lexicon and customs, including identification of uniforms and insignia.

With the February 1942 issuance of Executive Order 9066, the U.S. military barred Japanese Americans from the West Coast, ordered them to internment camps, and classified them as ineligible for service. Most Nisei already in the military were transferred to inland bases with no prospect of deployment. The school, too, had to move. Before doing so, the program commenced its first graduates: 40 Nisei students and two white reserve officers—both born to English-teaching parents in Tokyo. The remaining 28-some students had failed to meet the school’s high standards.

Shortly after the May ceremony, the school relocated to a rundown former Civilian Conservation Corps facility in Saint Paul, Minnesota, aptly named Camp Savage. Now named the Military Intelligence Service Language School, after the War Department had consolidated the army’s intelligence functions into the new Military Intelligence Service, the school was placed under Rasmussen’s command. A new class of 200 students began lessons there on June 1, 1942.

The first graduates, meanwhile, received their initial assignments. Ten Nisei went to Camp Savage as instructors. Five were sent to Alaska to help monitor Japanese radio traffic in the Aleutian Islands. Major David W. Swift, one of the two white graduates, led a team of eight Nisei to General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific headquarters in Australia to establish what would soon become the Allied Translator and Interpreter Section. The remaining graduates, including Captain John Burden, the other white officer, were assigned in small groups to units throughout the South Pacific.

Field commanders at this stage knew little of the linguist program and were leery of the Nisei soldiers. The first group to reach South Pacific headquarters in New Caledonia pulled driving or guard duty for weeks before being given the opportunity to scrutinize enemy communications in preparation for ground offensives in the Solomon Islands. “There was this innate distrust or fear of us that we had to overcome,” Jim Masaru Ariyasu, an MIS linguist, recalled in a 2006 interview. “We were in the midst of white officers, even generals, who were not in total confidence of us, and other GIs would look suspiciously at us and wonder what we were doing.”

After Burden arrived in Guadalcanal in October 1942, he convinced his superiors to deploy MIS teams to forward areas where they would have their first opportunity to interpret real-time intelligence. These Nisei linguists translated a captured Japanese operations plan that revealed locations of key armaments and ammunition, helping Allied forces anticipate enemy movements and secure Guadalcanal by February 1943. The Niseis’ performance proved invaluable to their fellow soldiers on the frontlines. “I am glad to say that those who opposed the use of Nisei the most are now their most enthusiastic advocates,” Burden would write to the school that March.

WECKERLING AND RASMUSSEN had been right in their predictions; commanders across the Pacific were soon begging for Japanese linguists. The army filled the order by combing through the ranks of Japanese Americans already in uniform.

Hiroyuki Nishimura, 24, was one such recruit. He had been drafted in February 1942 during his freshman year at the University of Washington and was stationed at Camp Crowder, Missouri, when MIS recruiters came calling. As a boy in Seattle, Nishimura had grudgingly clocked hundreds of after school hours hunched over textbooks in Japanese language classes while his white peers rounded the bases of nearby ballfields. He half-heartedly completed the recruiters’ tests but protested, “I have no appreciation for Japanese—too hard.” A week later, the army ordered him to Camp Savage.

About one in eight Nisei born on the mainland United States had been sent to Japan for part of their education by parents who favored their homeland’s school system. Although the U.S. government was particularly distrustful of these individuals, known as Kibei, they were highly prized recruits for the MIS.

While stationed at Fort Warren, Wyoming, in July 1942, Oregon-born Takashi Matsui, a Kibei educated in Fukuoka, Japan, was overheard poking fun at the poor translations in a Japanese pamphlet in the library. He was soon sent to Camp Savage, where Rasmussen tested his language skills and put him on a fast-track to graduate with its first class in December. Shortly after, Matsui was appointed an instructor. By then the school had plucked most suitable candidates from the existing army ranks and received permission from the War Department to dispatch Matsui and other instructors to administer language tests at internment camps, offering high-scoring Nisei the chance to trade their barbed-wire confines for khaki uniforms. Nearly 2,000 internees volunteered for army service—among them Roy Matsumoto.

Many Nisei joined the MIS because it gave them the opportunity to serve and to prove their allegiance to the United States. But some who volunteered from the camps faced opposition from peers and family who believed Nisei should not aid the army that had incarcerated them. Daisuke Kitagawa, a minister interned at the Tule Lake War Relocation Center in northeast California, recalled the tense atmosphere in which many of the camp’s Nisei volunteered despite the objections of their Issei, or first-generation immigrant parents. As he wrote in his memoirs, “Some acted secretly; some after several days and nights of bitter argument with their parents.”

RASMUSSEN TRUSTED THE task of preparing the MIS linguists for the field to John F. Aiso, a prominent Harvard-educated Nisei attorney. As director of academic training, Aiso set extremely high standards for the Nisei, who made up 85 percent of the student population. He constantly reminded them that their performance would have a direct impact on Japanese Americans’ future in the United States.

Most recruits rose to the challenge. At Camp Savage, students attended seven-hour classes each day, mastering not only the language and military customs, but Japanese history and culture, document analysis, and interrogation techniques. After two more hours of compulsory evening study, many stayed up late into the night, poring over their books in the ever-lit latrines. Medical staff would note a dramatic rise in the number of eyeglass prescriptions due to eye strain.

As Rasmussen received dispatches from the front about the effectiveness of the training program, Aiso adjusted the curriculum. He incorporated Japanese films into culture classes and recruited veteran linguists to visit as guest lecturers while home on leave.

Initially the school had taught harsh interrogation techniques. Instructors played the role of prisoner while students relished the opportunity to shout and threaten them with violence when they resisted cooperation. But as early as the Guadalcanal Campaign, linguists in theater reported that such measures were unnecessary. Since Japan’s “code of honor” called for suicide above surrender, its soldiers were ill-prepared for capture. Prisoners who had expected to be tortured and killed were stunned by the humane treatment they received and often answered their captors’ questions without hesitation, relieved to learn that the Nisei were Americans rather than disguised Japanese officers sent to punish them for being captured. On rare occasions when prisoners resisted questioning, linguists could usually secure their cooperation by simply stating that the Red Cross would notify the prisoner’s spouse or parents that he had been captured alive—an act that would bring shame to the family. The school accordingly began teaching more compassionate interrogation methods.

Despite the Nisei students’ exceptional academic performance, they remained under constant Counter Intelligence Corps surveillance for any signs of possible disloyalty. With few exceptions, the War Department refused to commission them. To cultivate leaders for the linguists, the MIS Language School continued to recruit white soldiers with knowledge of Japanese language and customs or with high intelligence test scores. When the War Department requested language personnel, Aiso and a group of advisers handpicked students for assignments. Typically, a white officer was matched with a team of Nisei soldiers trained as interrogators, interpreters, and translators. Although the teams wore U.S. Army uniforms, they could be attached to the Marines, U.S. Navy, or allied militaries.

The increasing demand for linguists led the MIS Language School to relocate to larger facilities at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, in August 1944 and expand its admissions to include 50 Nisei members of the Women’s Army Corps and linguists of other races. But the majority of MIS linguists remained Nisei men, who served in the field at great personal risk. If captured, they could be tortured or executed as traitors, and any family still in Japan might face reprisal. Interaction with friendly troops also posed dangers, as Nisei were sometimes mistaken for the enemy. So when Nisei reported for field assignments, they were typically paraded before their new units to reduce the risk of friendly fire. The strategy was not foolproof, however, as Hiroyuki Nishimura learned while serving with the 26th British Indian Infantry Division in Burma in late 1944.

One evening, while Nishimura was staking a bivouac in the dense jungles north of Rangoon, a group of British soldiers from a neighboring camp detained him, suspecting he was a defecting Japanese fighter disguised in a U.S. Army uniform. By the glow of a kerosene lantern, a British commander studied Nishimura’s face while the Indian sergeant assigned as his bodyguard nervously vouched for his identity. After confirming the story with headquarters, the British officer dismissed the rattled pair back into the night.

California-born Harry Akune, a Kibei who had volunteered for the MIS from a Colorado internment camp, had a close call in the Philippines. In February 1945 the commander of the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regimental Combat Team asked Akune to accompany his men as the single linguist on an airborne attempt to retake Corregidor, the small Japanese-held island fortress guarding the entrance to Manila Bay. Akune agreed and on February 16, made his virgin parachute jump onto the island with a borrowed rifle and no helmet. After missing the landing zone, Akune scrambled up an embankment to find half a dozen American rifles pointed at him.

“I thought, ‘Oh my God. If one of them let go, all of them’s gonna let go. I’m gonna be full of holes,’” Akune recalled in a 2003 interview for Densho, an online digital repository of Japanese American history. He threw down his rifle and raised his hands just in time for one of the men to recognize him and order the others not to fire.

As the 503rd established a perimeter on the island, Akune sifted through captured documents as quickly as he received them and soon discovered that the 850 enemy troops they had expected to find on the island actually numbered more than 5,000. The intelligence allowed the 503rd to plan an effective attack and within two weeks Corregidor was in American hands.

These and other MIS missions were top-secret, as MacArthur and fellow commanders were adamant that the Japanese not discover one of their most valuable intelligence assets. The Nisei soldiers of the MIS achieved some of the greatest intelligence feats of the Pacific War, interpreting the information that led to the April 1943 assassination of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto and translating the captured Z Plan, which exposed Japan’s 1944 South Pacific defense strategy. Their operations stretched from Washington, DC, to Delhi, and ranged in scope from translating progress reports on Japan’s atomic weapons program for the Manhattan Project to questioning prisoners taken during hostile beach landings. Years later, MacArthur’s chief of intelligence, Major General Charles Willoughby, would say the Nisei “shortened the Pacific War by two years and saved possibly a million American lives and saved probably billions of dollars.”

THE JAPANESE SURRENDER signaled a new era for the MIS. With the lifting of Executive Order 9066, the MIS Language School moved to the Presidio of Monterey, California, in June 1946. Over the next seven years, some 3,000 Nisei linguists would use their translation skills in occupied Japan, drafting the new constitution, liaising between U.S. authorities and local populations, and repatriating Japanese citizens from former territories.

Nisei soldiers arriving in Japan for the first time were often eager to explore their heritage. For Kibei, occupation assignments often prompted family reunions. After four years as an MIS instructor, in 1946 Takashi Matsui was reassigned to lead an interrogation unit in Japan. Before taking his new post, the army offered him leave to visit his parents in Fukuoka. Matsui was later among about 70 Nisei linguists who assisted with Japanese war crimes tribunals.

Occupation duties also provided an unexpected reunion for Roy Matsumoto, who had assumed that his parents and five siblings were killed when the first atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima. While interrogating Japanese POWs in China in 1946, Matsumoto recognized a cousin’s name on a prison roster. His cousin informed him that his parents had moved from Hiroshima to the countryside before the bombing. Eventually, Matsumoto would be reunited with his entire family—including two brothers who had served in the Japanese military.

IN 1963 THE MIS Language School became the Defense Language Institute, which today trains U.S. and foreign linguists in more than two dozen languages. The Nisei MIS achievements remained classified until 1972 but, as John Aiso had predicted, their outstanding performance—along with the distinguished service of the Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team and 100th Infantry Battalion in Europe—helped stem the tides of racism and create new opportunities for Japanese Americans in the United States. In 1981 Hiroyuki Nishimura was one of hundreds of Nisei who provided testimony to the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, which would eventually offer apologies and reparations to the internees.

The MIS linguists received the Congressional Gold Medal in 2010, adding to a long list of individual valor decorations. Aiso and Harry Akune were both inducted to the Mili-tary Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame, along with Roy Matsumoto, who also received the Legion of Merit and was named to the Army Ranger Hall of Fame. With the signature humility of his generation, Matsumoto dismissed the accolades in a 2003 interview for Densho. “I have the knowledge that we survived, and that’s the most important thing for me,” he said. ✯