In the spring of 1940, Nazi officials launched AB-Aktion (Ausserordentliche Befriedungsaktion, or “Extraordinary Pacification Action”), the second phase of a systematic campaign to eliminate intellectuals, politicians, clergy, and other influential leaders in German-occupied Poland. Those the Nazis targeted were either placed in concentration camps or murdered by paramilitary death squads at secret locations. One series of mass executions took place in a secluded forest near the small village of Palmiry. The dead included Janusz Kusociński—an Olympic hero, decorated soldier, and national icon.

Janusz Tadeusz Kusociński was born on January 15, 1907, in Warsaw. Armed conflict would take a heavy toll on his family, beginning with his oldest brother, Zygmunt, who was killed in France during World War I. Another brother died in the Polish-Bolshevik War in 1920. Young Janusz showed early potential on the football pitch and also excelled at palant, a popular bat-and-ball sport similar to baseball. His athleticism continued to develop after he joined the sports club RKS Sarmata, where he picked up the nickname “Kusy,” but after falling behind in school, his father sent him to the State Secondary School of Horticulture so he could learn a trade as a gardener.

The chances of Kusociński becoming an Olympian runner, let alone a gold medalist and world record holder, appeared slim. But as fate would have it, after being pulled from the grandstands as a last-minute replacement at a track meet in 1925, the feisty 18-year-old, who stood 5′ 5″ with a modest build, responded with an impressive performance, propelling his club to victory and setting in motion an improbable path to glory.

Kusy soon attracted the attention of Estonian decathlete Aleksander Klumberg, who had recently been named head coach of Polish national athletics. Klumberg, a bronze medalist at the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris, recognized the young man’s raw potential and encouraged him to embrace a more rigorous workload involving gymnastics and intense interval training, similar to the training elite Finnish runners of the day employed. The plan worked. Beginning in 1928, Kusociński won the first of 10 Polish titles in events ranging from 800 to 10,000 meters while setting 25 national records.

Kusociński had to place his running career on hold while he completed two years of compulsory military duty in the Polish Army. As a member of the 36th Legion Infantry Regiment, he achieved the rank of corporal before completing his service in 1930. He then resumed his winning ways, capturing national titles for 800, 1,500, and 5,000 meters and cross country. His grueling training regimen saw him work out twice a day, which he scheduled around his job as a gardener at Łazienki Park, the largest open-air grounds in Warsaw. He understood that unwavering dedication and discipline were vital if he wanted to beat the world’s best athletes. In his biography, he described the austere training he undertook: “Regardless of snow or rain, gale or frost, dressed as warmly as possible, in a few sweaters, I run Lazinki Park.”

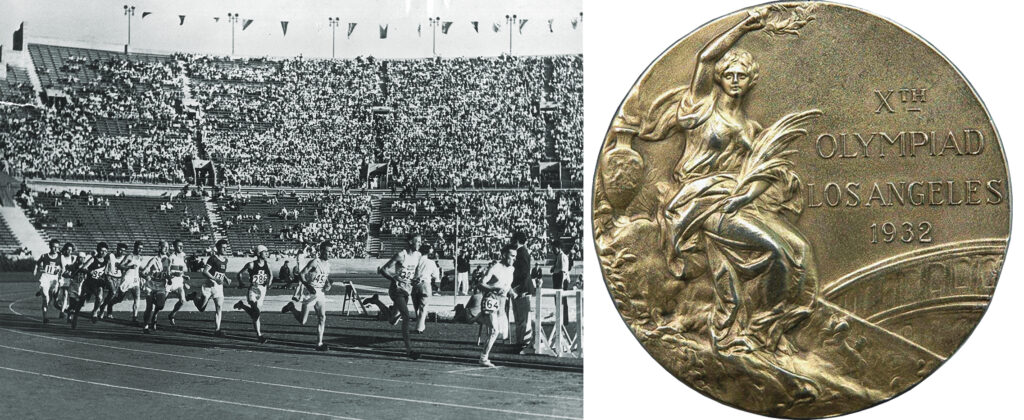

Throughout the 1920s, Finland’s Paavo Nurmi domi-nated middle- and long-distance running, winning nine Olympic gold medals. But his iron grip on the sport had begun to slip, and even Finnish newspapers were now hailing Kusociński as the “Polish Nurmi.” In June 1932, Kusy broke the world record for 3,000 meters with a time of 8:18.8. Less than two weeks later, he shaved 13 seconds off the four-mile all-time best, clocking 19:02.6. Both records had previously belonged to Nurmi. The Warsaw runner then set his sights on representing his country that summer at the Olympic Games in Los Angeles—and a showdown with the “Flying Finns.”

Some runners effortlessly bound down the track with the grace of a gazelle. Not Kusy. He ran ugly—more like a charging rhino—working hard every step of the way. This contrast set the stage for the Olympic 10,000-meter final, featuring a clash between the Pole and two Finnish runners, Volmari Iso-Hollo and Lasse Virtanen (Nurmi didn’t compete after being disqualified on allegations of violating the amateur code). Adding to the drama, a new pair of track spikes gave Kusociński cuts and blisters on both feet and he ran the last eight laps in excruciating pain. Entering the bell lap, he trailed Iso-Hollo before kicking past his rival on the final curve en route to a new Olympic record. Poland now had its first-ever male Olympic champion.

His elation, however, was short-lived. The deep lacerations on his feet forced him to withdraw from the 1,500-meter and 5,000-meter events—races in which he was expected to medal. Although disappointed, Kusociński returned home a conquering hero, regaling people with stories of his 10k triumph and how he met Hollywood stars Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and Tom Mix. Kusy’s own celebrity led to packed stadiums whenever he competed, and his races were often broadcast on the radio. But his relentless drive for success had become a double-edged sword. An innate stubbornness and high pain threshold eventually led to multiple surgeries to repair the degenerative menisci on his knees. While recovering, Kusociński utilized the downtime to explore some new avenues, including coaching, pursuing a degree in physical education, and becoming editor-in-chief of Poland’s oldest daily sports newspaper, Kurier Sportowy.

Lingering injuries prevented him from defending his Olympic title in 1936. Nonetheless, he attended the Games in Berlin as a reporter and technical adviser to the Polish athletics team. At the German capital, which featured the largest Olympiad to date, the world witnessed Adolf Hitler blatantly propagandize his master race ideology. The heroics of American Jessie Owens aside, the home team ruled the podium, hauling in a total of 101 medals.

In 1939, Kusy made a triumphant return to the track, winning the 10,000-meter event at the Polish championships. He capped the season by breaking the national record twice for 5,000 meters and looked forward to taking another crack at the Olympics the following year, with an eye on the marathon. The Games of the XI Olympiad had been originally awarded to Tokyo, but a confluence of factors, including Japan’s war with China, resulted in Olympic organizers naming Helsinki as the replacement host city. Such details, however, are now a trivial footnote in history. Both the 1940 and 1944 Games were canceled because of World War II—hostilities that were sparked by Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939.

Hitler attempted to justify the attack by falsely claiming German forces had acted in self-defense, stemming from “false flag” incidents staged along the Polish border. The deceit included a fake assault on a radio station in Gleiwitz—a ruse involving murder victims dressed in Polish Army uniforms. The Wehrmacht wasted little time before unleashing more than 2,000 tanks supported by massive air cover from the Luftwaffe.

The offensive also introduced a new term to describe the Nazis’ fast-moving tactic: blitzkrieg (“lightning war”). Created in response to Germany’s failures in WWI and the need to overcome trench warfare deadlock, blitzkrieg hinged on the ability to penetrate a weak point in an enemy’s line while launching unprecedented speed of movement on the battlefield.

The battleship Schleswig-Holstein fired the opening shots of World War II when it unleashed its guns from the port of Danzig (Gdańsk) on the Polish garrison at Westerplatte. German ground forces, spearheaded by 11 Panzer divisions, rolled into Poland on several fronts, closely supported by Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers. Army Group North, under General Fedor von Bock, launched a two-pronged attack with the Third Army advancing south from East Prussia and the Fourth Army pushing east across the Polish Corridor to seize Danzig. Meanwhile, General Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group South attacked from southeastern Germany and Slovakia.

At the outbreak of war, Kusociński attempted to enlist in the army, but his previous surgeries rendered him “category D” (incapable of active military service). Nonetheless, he volunteered with the 360th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Battalion, and posted to Czerniakowski (IX) Fort, a section of the outer ring that formed the Twierdza War-szawa (Warsaw Fortress). Built in the late 19th century under Russian Tsarist rule, the large, pentagon-shaped garrison secured the city from the south and featured a deep and wide moat. Kusociński, armed with a heavy machine gun and FB Vis 9mm pistol, commanded a platoon responsible for defending a bridge spanning the Vistula River.

German troops reached the southwestern suburbs of Warsaw by September 8. The undermanned and outgunned Poles managed to repel the initial attack before coming under siege as relentless artillery and aerial bombardment pounded the bustling, cosmopolitan city of 1.3 million. Making matters worse, the Soviet Union entered the war on September 17, having signed a secret pact with Germany to divide Poland in half. The lack of support from Western Allies further exacerbated the hopeless situation.

As enemy troops closed in on the fortress, Kusy was shot in the thigh but refused to leave his post. According to fellow soldier Józef Korolkiewicz, “At some point, Janusz Kusociński’s machine gun jammed. While the servicemen struggled with dismantling and cleaning the seized parts…he leaned out of his position and shot his Vis pistol towards the crawling Germans. A moment later, the machine gun re-launched. Almost simultaneously, Kusociński is wounded again. Despite being injured for the second time, he does not want to leave his position. Both his legs are now injured.”

Warsaw fell on September 28, 1939. For Kusociński’s actions, the Polish government-in-exile awarded him the Cross of Valor, a military citation awarded for “deeds of valor and courage on the field of battle.” He spent several weeks in a hospital, where nurse Zofia Biernacka treated his wounds. Years later, she recalled her encounter with the famous Olympian: “I remember that during dressing changes, looking at his small and slim legs, I wondered how he could achieve such world-class success. I even made a note about it during the dressing. Then I heard the answer: ‘At the stadium, I was driven by ambition and love for my homeland.’”

After recovering, Kusy became involved with the Polish Resistance, joining an underground military organization called “Wolves.” He adopted the pseudonym “Prawdzic” (“True”) and took a job as a waiter in the Pod Cockem, a popular bar that allowed him to pass along critical information. The position also him put under surveillance by the Gestapo, who arrested him on March 28, 1940, in front of the house he shared with his mother and sister. Over the next three months, the Nazi secret police carried out lengthy interrogations marked by routine beatings and torture. Most of the abuse took place at Pawiak Prison, which more or less served as an inner-city concentration camp for political prisoners or anyone considered a threat to the Third Reich. The Nazis used a variety of methods to extract information, such as starvation, dog attacks, and ripping out fingernails. Kusy gave them nothing.

Mass executions had been taking place in Poland since the start of the German occupation. Although early campaigns specifically targeted Polish leadership from academic, political, and cultural circles, the massacres served as a prelude to genocide throughout Europe that culminated with the Holocaust. Executions during AB-Aktion were usually carried out by SS units and the Ordnungspolizei (“Order Police”). In an effort to maintain secrecy, the Nazis shifted the killings to the Kampinos Forest, located near the village of Palmiry, about 19 miles northwest of Warsaw. There, Nazi officials undertook several precautions to carry out their plans. Forestry crews cut down trees to enlarge a clearing; the Arbeitsdienst (Reich Labor Service) dug graves in the shape of long ditches, assisted by members of Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) who camped nearby; and German police undertook intensive patrolling to secure the area.

Transport trucks departed Pawiak at dawn to give prisoners the impression they were going to another prison or labor camp. Nazi officials reinforced the subterfuge by allowing them to take their documents and luggage. Some victims who saw through the ruse tossed out hastily written letters and personal items from the trucks. Upon arrival at the murder site, the condemned men and women were forced to line up along the edge of the pits, blindfolded. The Nazis shot them with machine guns, then killed anyone still alive with pistols. After filling in the ditches, work crews added a layer of moss and planted pine trees over the graves.

From 1939 to 1941, the Nazis murdered more than 1,700 Poles in the massacres at Palmiry. Records show that 358 victims, including Kusociński, were murdered in a single operation on June 20-21, 1940. According to eyewitness accounts, Kusociński had been severely beaten and could barely stand. Two other Olympians died with him: sprinter Feliks Żuber and cyclist Tomasz Stankiewicz.

Although the perpetrators went to great lengths to carefully cover up their crimes, the deaths at Palmiry would eventually be exposed. Local residents and Polish forest service workers knew about the executions and had marked the location of the graves. After the war, Poles exhumed hundreds of bodies, including the remains of Kusociński, found with fragments of a striped suit, a comb he received from his sister while in prison, and a figure of St. Anthony. Polish authorities later transformed the area into a war cemetery and established the Palmiry Museum-Memorial Site. Among the long rows of burial plots, Kusy’s gravestone stands tallest.

Those directly involved in the murders were never held responsible, except for SS-Standartenführer Josef Albert Meisinger. Known as the “Butcher of Warsaw,” Meisinger had authorized the killings at Palmiry while serving as commander of the Security Police in the Warsaw District. After the war, Meisinger was tried by Polish authorities and hanged at Mokotów Prison in March 1947.

The legacy of Janusz Kusociński remains a source of immeasurable national pride in Poland. There are several schools, streets, athletic facilities, a Polish Ocean Lines ship, and an airplane of LOT Polish Airlines that have been named after him. In 2009, the Polish government posthumously awarded Kusociński the Commander’s Cross with Star of the Order of Polonia Restituta “for outstanding contribution to the independence of the Polish Republic, and for sporting achievements in the field of athletics.”