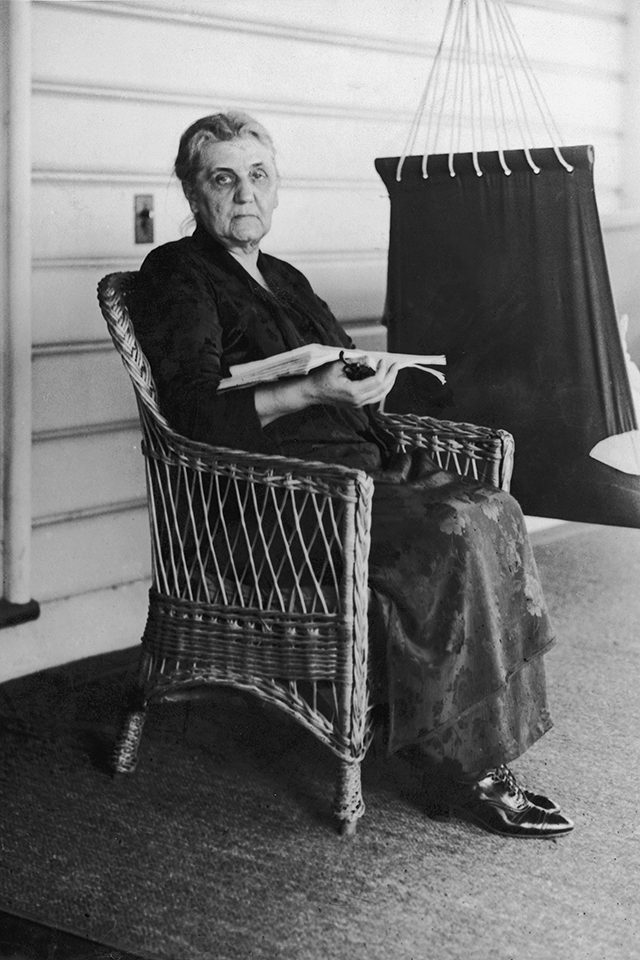

Progressive heroine’s reputation suffered when she tried to sell pacifism as patriotism

ON SUNDAY MORNING, JUNE 10, 1917, well-known activist Jane Addams stood at the podium of First Congregational Church in Evanston, Illinois. The atmosphere was electric. The pacifist sentiments Addams had long espoused had been drawing more and more criticism as the war in Europe ground on. In April, to her dismay, America had thrown in with the Allies against the Central Powers. Addams nonetheless was holding to her path, delivering speeches like the text before her on the rostrum entitled “Pacifism and Patriotism in Time of War.”

Addams had come to First Congregational knowing full well that she would encounter skeptics. This day was no different and yet more intense. As the activist spoke, her listeners, who included longtime friend and ally Orrin N. Carter, chief justice of the Illinois Supreme Court, sat in hostile silence until Addams delivered the line

“Opposition to the war is not necessarily cowardice.”

Justice Carter sprang to his feet.

“Anything that may tend to cast doubt on the justice of our cause in the present war is very unfortunate,” the jurist declared. “No pacifist measure, in my opinion, should be taken until the war is over.”

Addams had heard worse, but now she was enduring what may have been the most discomfiting public moment in a life that until recently had been one of fulfillment, accomplishment, and above all popular approval. A staunch progressive, Addams had won Americans’ hearts by founding Hull House, a pioneering social action center in Chicago, by being a force on behalf of woman suffrage, by speaking out against imperialism, and by advocating for workers. Now pacifism had made her a pariah, a role for which nothing in decades of public service and public approbation had readied her.

Jane Addams was born in 1860 in Cedarville, near Rockford, Illinois. The youngest of four children, she was two when her mother, Sarah Weber Addams, died. At four, the girl developed spinal tuberculosis, which left her with a crooked spine and a lifetime of ailments. Her father, an enterprising mill and factory owner, had been a friend of young Abraham Lincoln. John Addams encouraged his adoring youngest to read—she especially loved the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson—discussed current events with her, and introduced her to political figures. He represented Cedarville for seven terms in the state Senate. Himself raised a Quaker, John Huy Addams did not bring up his children in a particular church, but Jane wrote later that he connected her to “the moral concerns of life.” A grave, thoughtful child, she announced that she wanted to live among the poor, perhaps practicing medicine—at which point her vision and her father’s sharply diverged. Though Jane excelled at Rockford Female Seminary, a local college, her father refused to approve her request to transfer to more rigorous Smith College in Massachusetts. Like most men of his era, John Addams focused his ambitions on his son, Harry.

Jane Addams was not alone in feeling a patriarchal thumb on her aspirations. “She hides her hurt,” she wrote of the her generation of middle-class Americanwomen. “Her zeal and her emotions are turned inwards, and the result is an unhappy woman, whose heart is consumed by vain regrets and desires.” Jane barely had graduated from seminary in 1881 when John Huy Addams suddenly died. The loss of her father and a substantial inheritance enlarged his daughter’s possibilities, but what Jane Addams later called “the family claim”—the unwritten assumption that a young single woman’s first duty was to family, in her case siblings and stepmother—outweighed any wish to engage with the world.

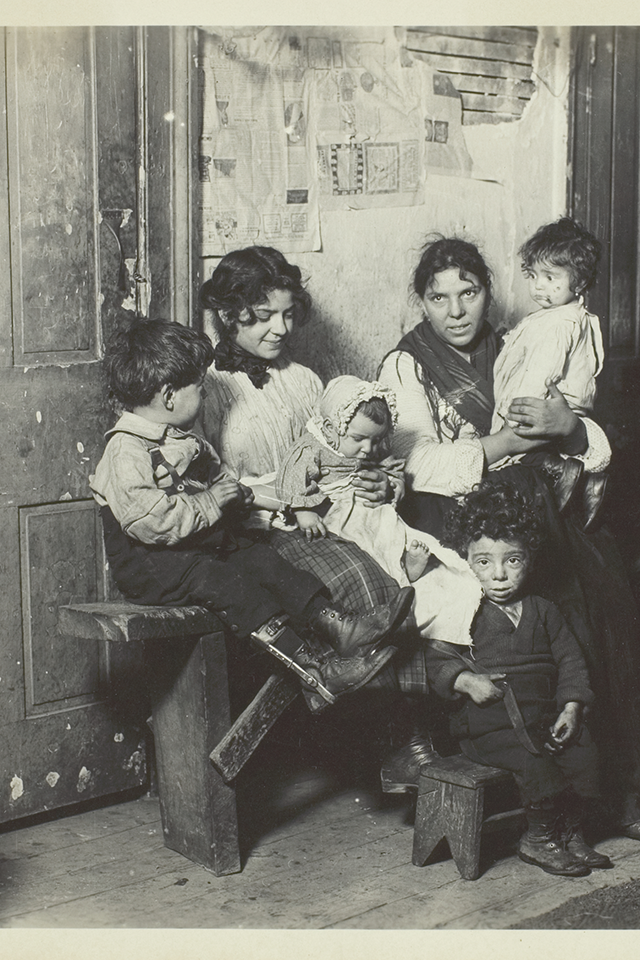

In this wish to engage, Addams had company. The Civil War having claimed hundreds of thousands of men with whom women might have made matches, Addams’s female peers stepped into more diverse and meaningful roles, paid or unpaid, in a society transformed by the typewriter, the sewing machine, and other labor-saving, job-creating inventions. Industrialization and immigration had cities bursting at the seams—overcrowded, filthy, and disease-ridden. A collective reform impulse emerged, bringing women like Addams fresh prospects and role models in a movement eventually labeled “progressivism.”

After John Addams died, the family moved to Philadelphia, where Harry entered medical school. Jane also took classes, but back trouble led to a mental breakdown and hospitalization. Nerve specialist S. Weir Mitchell convinced Jane, as he had many other young women, that her physical woes stemmed from self-absorption and failure of will. Returning to Cedarville, she earnestly embraced Mitchell’s diagnosis, eschewing self-pity and striving to be “the highest, gentlest and kindliest spirit.” A risky spinal surgery and a long recovery restrained in a heavy corset further tested her.

Finally, in early 1883, Addams set off with friends and relatives on the traditional “Grand Tour” of the Continent popular with young adults of her class. Addams found herself riveted by industrial London’s “dark heart,” the East End. Historically a locale of docks, slaughterhouses, and other “noxious trades,” the East End crammed into tenements London’s poorest residents. One Saturday evening, a missionary the young American had met at her boarding house took Addams on a tour of the district, where dilapidated housing looked onto streets dense with beggars, urchins, animal carcasses, and filth. Addams gaped at East Enders scrabbling to buy decaying meat and decaying produce, a penitential contrast to the culturally elevated circuit she had been making of authors’ graves, museums, and theaters around the city. “All huge London came to seem unreal save the poverty in its East End,” she later wrote.

To Addams, the East End seemed a personal reproof that she considered as she toured the Continent, gravitating unblinking to city upon city’s poorer quarters. At home, she bristled at her stepmother’s preoccupation with the social whirl; she and her father’s widow fell out permanently in 1887, when Jane’s stepbrother proposed marriage and Jane rebuffed him.

Reverberations of her experiences in the East End led Addams to seek insight in faith. Schooled in the Bible at college, she pondered Christ’s example. An 1886 translation of Leo Tolstoy’s My Religion: What I Believe, chronicling the Russian count’s efforts to emulate Christ in embracing poverty and nonviolence, captivated Addams. But she did not know what meaningful action to undertake.

Addams found her course in late 1887, reading in Century magazine of Toynbee Hall, a British “settlement house.” For decades, would-be reformers in America and England had struggled to fight urban poverty. Neither government had programs for disadvantaged citizens beyond pointedly harsh municipal poorhouses, poor farms, or workhouses; the indigent had to look to private charities, churches, and beggary.” In Britain, radical thinkers were finding inspiration in the writings of economist and social theorist Arnold Toynbee, who favored transmitting values over palliating poverty with donations. Adherents of Toynbee had installed progressively inclined privileged individuals in slums to offer neighbors fellowship and learning. These “settlers” and their “settlement houses,” while paternalistic, sought to reach across class lines.

As the Century article explained, East End clergyman Samuel Barnett and wife Henrietta had bought a disused school near their rectory. The couple invited 15 Oxford graduates to move into the building’s upper floors, naming their project for Toynbee. The young men had day jobs elsewhere in London, but after working hours offered neighborhood residents classes and cultural programs convened on Toynbee Hall’s main floor. The settlement workers also investigated social conditions in the neighborhood.

Bearing a letter of introduction, Jane went to London and looked up the Barnetts. The couple introduced their visitor to the Oxford contingent and its activities. Toynbee Hall was “so free from ‘professional doing good,’ so unaffectedly sincere and so productive of good results in its classes and libraries that it seems perfectly ideal,” Addams wrote to her sister Alice.

Energized, Addams moved to Chicago, where industry had attracted a large immigrant population. When the city’s west side was still green, industrialist and developer

Charles Jerald Hull had built a country house there. Hull recently had died, and now his Italianate mansion stood in a polyglot slum. The three-story brick pile at 800 South Halsted Street looked to Addams as if it could be a Toynbee Hall. Hull’s heir agreed to rent the place, eventually forgoing payment. Addams paid for renovations out of her inheritance. In 1889, she, seminary classmate Ellen Starr, and a housekeeper moved in. New York City boasted America’s first settlement house, the Neighborhood Guild, founded in 1886 on the Lower East Side, but Hull House was the first staffed with female settlers.

.

Addams wanted Hull House to be a community center and source of moral uplift. Her neighbors at first were wary but soon youngsters were flocking to afternoon art classes and adults to evening receptions and cultural programs. Visitors liked the entertainment but pushed for practical help with employers, garbage removal, and ethnic frictions. Within the year, Addams was mediating labor disputes.

Hull House’s success drew allies and applicants seeking to work and live there. As Addams and Hull House exerted more influence, the reputations of both grew—as did the operation itself, eventually occupying 13 buildings. Over the years, dozens of female reformers resided at Hull House, their experience often carrying into other projects.

After Addams convinced union organizer Mary Kenney to help with neighborhood labor disputes, Kenney moved into Hull House; years later, she founded a settlement house in Boston. Fleeing an abusive spouse, activist Florence Kelley moved into Hull House; her interest in urban research and lobbying got Addams thinking about politics and power. When University of Chicago professors like John Dewey lectured at Hull House, a partnership was born. Settlement houses multiplied in American cities. By 1900 there were 100, mostly staffed by young women.

In early 1894, Addams helped found the Civic Federation of Chicago, which sought to improve city services by allying business, labor, and academic leaders to exert collective pressure. That spring, industrialist George Pullman cut wages and laid off workers at his enormous Chicago railcar factory. The American Railway Union, whose members built, operated, and maintained rail equipment, called a strike against Pullman. Addams, resolutely remaining impartial, led the federation in attempting to negotiate a settlement. The effort failed. The strike against the railroads went nationwide, stirring violence and ending in federal intervention by President Grover Cleveland. Both sides attacked Addams, who, shocked by the vitriol, emerged highly regarded for her evenhandedness. For this and similar efforts, organizations showered Addams with honors. The Daughters of the American Revolution made her an honorary member, for instance.

Addams began to receive requests to speak before civic and other groups. Eyeing her bank balance, eroded by outlays to renovate and operate Hull House, she saw in lecturing and writing the opportunity for a revenue stream. Her renown soon had other progressive groups, including national and international suffrage organizations, proffering leadership roles.

The 1898 Spanish-American War and concern about European militarism had spurred a growing pacifist movement. Another offshoot of progressivism, this cadre, Addams included, viewed war as an outdated barbarity that could be rendered obsolete by an international body dedicated to peaceful mediation of international disputes. In 1911, Andrew Carnegie put up $10 million for an Endowment for International Peace. Philosopher William James and colleagues, noting war’s emotional

appeal, advocated a “moral equivalent,” perhaps national service, to bearing arms.

By 1912, Addams was well regarded enough to be tapped to place fellow progressive Theodore Roosevelt’s name in nomination as Progressive—or “Bull Moose”—Party candidate for the presidency. Roosevelt was anything but a peacemaker. The presidency had deepened his belief that “by war alone can we acquire those virile qualities necessary to win in the stern strife of actual life.” Addams believed in a life of mutual and democratic engagement but, even though she saw war as being intrinsic to Roosevelt’s worldview, she nominated him. Roosevelt lost.

When Europe did go to war in August 1914, a revitalized peace movement drew Addams into its international leadership. The following January, she and others of like mind founded the Women’s Peace Party in Washington, DC; the group named Addams its president. The party endorsed “continuous mediation” of the European war conflict by neutral nations. In 1915, most Americans opposed taking a side. This wariness encouraged the peace group to hope President Woodrow Wilson would identify the United States, a neutral nation, as a negotiator. Wilson met and exchanged letters with Addams but the president committed to nothing.

In April 1915, Addams and other Women’s Peace Party representatives sailed to the Netherlands for an International Congress of Women. At The Hague, many of the 1,500 pacifists, enthusiastically embracing the continuous mediation concept, knew Addams from international suffrage meetings; they named her the event’s president.

After the congress, she and other envoys toured warring and neutral countries, talking with foreign ministers as well as wounded soldiers and civilians. As the fact-finding tour was under way, a German submarine torpedoed the liner Lusitania off Ireland, killing Americans. Interventionists demanded the United States prepare for war; public sentiment for pacifism curdled.

Addams returned to America in July 1915 oblivious to the bellicose shift in national attitude. Addressing a peace rally at New York’s Carnegie Hall, she followed a written speech with extemporaneous remarks about meeting young military casualties in Europe, describing their complaints that “this war was an old man’s war” and their stories of needing a drink to make a bayonet charge. Addams said needing alcohol to fight exposed humanity’s fundamental goodness, rekindling her hope for the world. The next day’s papers excoriated her, and she came under persistent attack. In a letter to The New York Times, war correspondent Richard Harding Davis claimed Addams had impugned every soldier. “Miss Addams denies him the credit of his sacrifice. She strips him of honor and courage,” Davis wrote, calling her remarks an insult “flung by a complacent and self-satisfied woman at men who gave their lives.” A Louisville paper termed Addams “a foolish, garrulous woman.” Another derided her as “a silly, vain, impertinent old maid…who is now meddling with matters far beyond her capacity.” The New York Times said women lacked the intellect to grasp the notion of war and the soldier’s role.

Reporters pressed Addams to respond, but she refused. “The story had struck athwart the popular and long-cherished perception of the nobility and heroism of the soldier,” she wrote later, observing that critics fixated on her as “a choice specimen of a woman’s sentimental nonsense.” In October 1915, she wrote an essay on pacifism for the New York Independent. Critics again distorted her meaning. Letter writers spewed abuse at her. Promoters canceled lectures; when Addams did appear, she faced stony audiences or catcalls. Long-time allies shunned her. Friends like Justice Carter broke with her. “I do not suppose I shall ever be applauded in Chicago again,” Addams told an intimate.

Decades of popularity had not prepared Addams, 57, for censure. She experienced a crisis of confidence. “In the hours of self-doubt and self-distrust the question again and again arises, has the individual…the right to stand out against millions of his fellow countrymen?” she wrote. She slowly realized that she was but one target among many. The public at large and a war-hungry press were pummeling anyone identified with pacifism.

Addams pressed on. Through much of 1916, illness, perhaps stress-related, consumed her energies. That autumn, presidential candidates Roosevelt and Wilson both sought her endorsement, hoping her support would help capture ballots in Illinois and 11 other states that now allowed women to vote in presidential elections. Roosevelt, who had quit the Progressive Party, was a long shot for the Republican nomination. Addams, always generous to opponents, allowed the ex-president to visit her. Democrat Wilson, campaigning for a second term with the slogan “He kept us out of war,” sent Addams five dozen roses. That October, after deliberating, she came out for Wilson—but only his domestic policies. Wilson sent another bouquet.

In late February 1917, Addams, now associated with the latest incarnation of pacifist thinking, the Emergency Peace Federation, met with the re-elected Wilson to discuss alternatives to war. To have a seat at peace talks, the president insisted, the United States had to join the fighting, and in April, the United States did. To muzzle pacifist criticism, Wilson proposed the Espionage Act. The bill’s ban on “disloyal speech” would make dissent a crime. Addams testified against the measure, to no avail. The Espionage Act and amendments known as the Sedition Act became law.

Jane Addams achieved personal peace amid public ire by hewing to what she called her “vision of the truth” and the “obligation to affirm it.” During the war years, Addams sometimes spoke publicly—always monitored by government officials—never directly criticizing the government but rather recommending peaceable solutions to conflict. She discussed the principle of honorable dissent and the definition of patriotism. Listeners were truculently silent or openly hostile; some called for her arrest on charges of disloyalty, but no charges ever were brought.

Addams’s rehabilitation began even before the war had ended. In late 1917, American “food czar” Herbert Hoover recruited her as a spokeswoman for Wilson administration nutrition and conservation efforts. Addams toured the country urging Americans to rethink their eating habits, talking about how feeding the hungry could unleash “a new and powerful force.” Months later, presaging the approach he would take during peace talks at Versailles, Wilson incorporated into his Fourteen Points speech ideas from the 1915 peace congress Addams had steered at The Hague.

The 1918 armistice accelerated Addams’s comeback. Once again, the peace movement regrouped, and the following year Addams again was elected president—this time of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, dedicated to international goodwill and gender equality. Addams spent the 1920s promoting these goals, in the decade’s latter years drawing fire for advocating defense budget reductions. In response, the DAR rescinded her honorary membership. “I had supposed at the time that had been for life but it was apparently only for good behavior,” Addams joked. Increasingly fragile health tethered her to Chicago.

In 1931, the Nobel Committee awarded Addams, 71, its Peace Prize—the first American woman so honored. “In honoring Miss Addams, we also pay homage to the work which women can do for the cause of peace and fraternity among nations,” the committee declared.

Jane Addams died on May 22, 1935 and was hailed in a New York Times obituary as “a priestess of understanding among neighbors and of peace among nations.” She is buried in Cedarville. The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom is still active. The institution she founded on Chicago’s west side in 1889 stayed relevant through the 20th century, meeting immigrants’ social and cultural needs. Closed as a settlement house in 2012, Hull House is now a museum.