I can vividly remember the first few interviews I did with veterans of the Second World War. One was with Wendy Maxwell, who had been a secretary to General Hastings Ismay (later Lord Ismay), military adviser to the British War Cabinet. She’d attended cabinet meetings and all the Allied conferences and had been at Nuremberg, too. It seemed incredible that the very elegant lady sitting opposite me had been a witness to such enormous events and met so many towering figures from history. A few weeks later, I chatted with a Battle of Britain Spitfire pilot, Geoff Wellum, in his local pub. He was terrific, holding his beer in one hand, an ashtray in the other (that’s how long ago it was) and saying, “So, I’m in my Spit, and this Me-109 is bearing down on me…”

Over the next few years I talked to veterans all over the world: Germans, Austrians, South Africans, Australians, French, Indians, Brits, and, of course, Americans. I reckon I’ve visited more than 30 states in my time. It was a huge privilege; these veterans were a living, tactile link to the past and helped me shift from a world that, in my mind’s eye, was monochrome to one of vivid color.

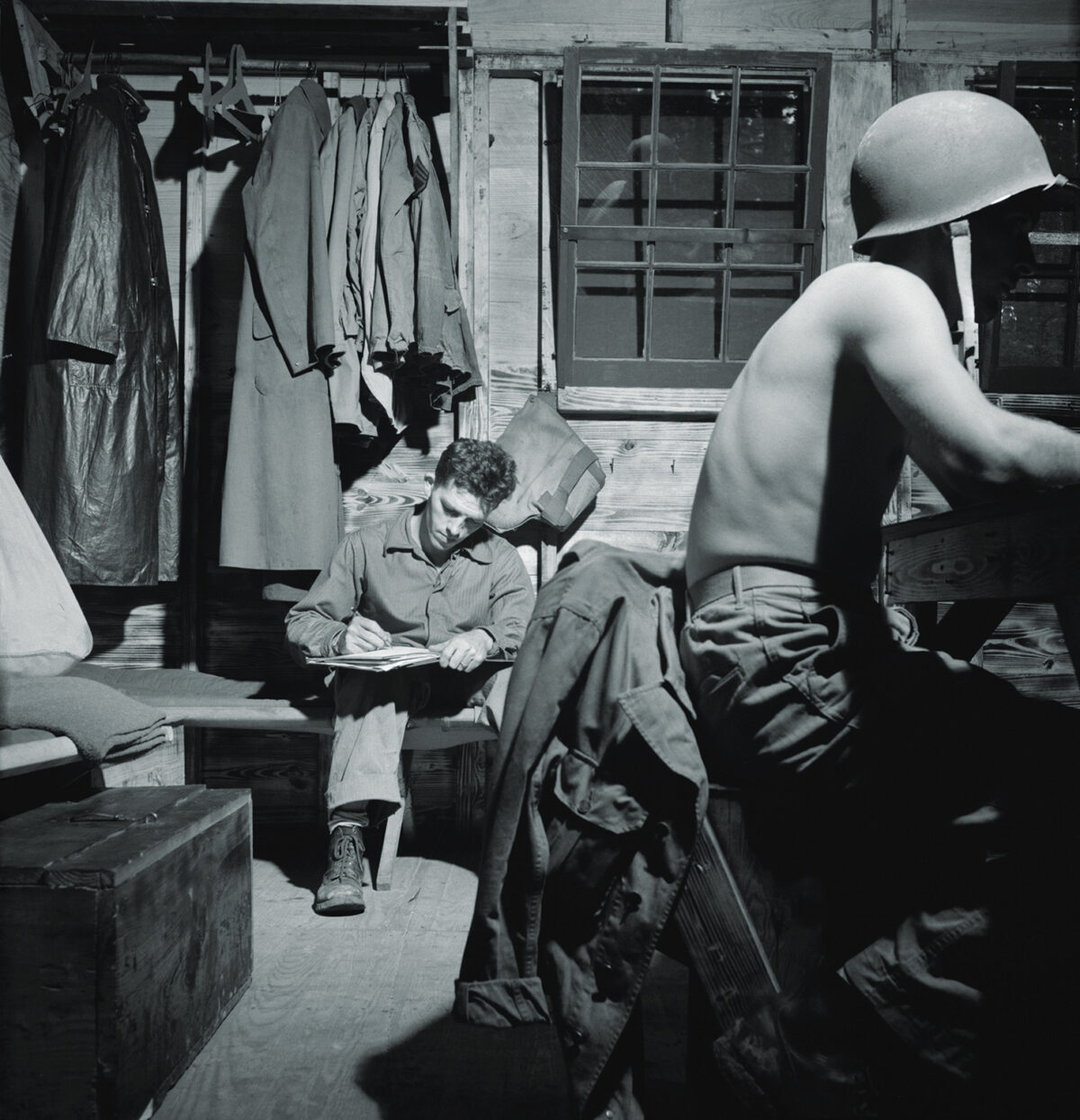

These 300 or so interviews of mine are all preserved, as are tens of thousands of others, so we do have an excellent—although sadly not comprehensive—global archive of veterans’ testimonies, but that greatest generation is now slipping away. It’s sad and makes me feel wistful and yet, as I have been discovering, there are still plenty of untapped voices from the war for the generations that follow to discover. A couple of years ago I was working on a book about a British tank regiment, and while I had a few interviews with veterans, I discovered it was the letters and diaries of those who served that were the most interesting and valuable. I was struck by their immediacy; after all, they had no idea how the war would play out, or even if they would make it through.

It was also astonishing how their young selves shone off every page. There was one 32-year-old tank commander who wrote the most touching letters back to his wife, full of longing, regret, hopes, and anxiety, but also of humor, too. I really felt I got to know him very well, and in writing about him was putting flesh back onto bones that had long ago been laid to rest. Another was a young officer who turned 21 on the day the Allies liberated Paris, August 25, 1944. He was very clearly a boy-man: old enough to command men and tanks in battle, but still young enough to be dependent on his parents and with a lack of worldliness that was very engaging. I cannot stress enough how upsetting it was to learn that he died less than a month later, on September 23.

I’ve since been doing some work on the Italian campaign and have deliberately decided to use contemporary sources as much as possible. The diaries and letters, written at a precise moment in time and on a particular day, are very moving. These servicemen obsess about letters from home and about aircraft in the skies. The Germans worry endlessly about the future, the fate of Germany, and what will happen to their families and homes back in the Reich. The Americans curse and grumble about the mud and rain but are extraordinarily stoic and phlegmatic. I’m in awe. One set of letters I’ve been reading are by an Australian serving in an Irish battalion who writes heartbreakingly to his wife about his best friend, a fellow officer, dying in his arms. It’s devastating to read, although even more tragic is that he, too, loses his life. And that’s it. The letters end.

I still believe oral histories are of immense value and feel very lucky to have spoken to so many veterans while I still had the chance, but men and women who are long gone from this world have been coming back to life for me in their words from 80 years ago, their young selves bursting from their pens. It has been utterly illuminating.