The ambitious Ohio Republican dreaded being caught up with congressmen in complicated railroad scheme

Wracked with dread on a wintry Tuesday evening in 1873, U.S. Representative James A. Garfield retreated to the pages of his diary. “At 11 o’clock went before the Credit Mobilier Investigating Committee and made a statement of what I know concerning the Company,” Garfield, 41, wrote. “I am too proud to confess to any but my most intimate friends how deeply this whole matter has grieved me. While I did nothing in regard to it that can be construed into any act even of impropriety much less than corruption, I have still said from the start that the shadow of the cursed thing would cling to my name for many years. I believe my statement was regarded as clear and conclusive.”

Garfield had appeared earlier on January 14 before a House committee investigating sweetheart stock sales by a congressman to colleagues. In the years after the Civil War, Washington was awash in sleazy deals, but Garfield had avoided the mire—until now. In sworn testimony, the Ohioan insisted he “never owned, received, or agreed to take any stock of the Credit Mobilier or of the Union Pacific Railroad, nor any dividends or profits arising from either of them.”

That night, as Garfield was scribbling in his diary, he feared permanent stain from the scandal consuming the capital.

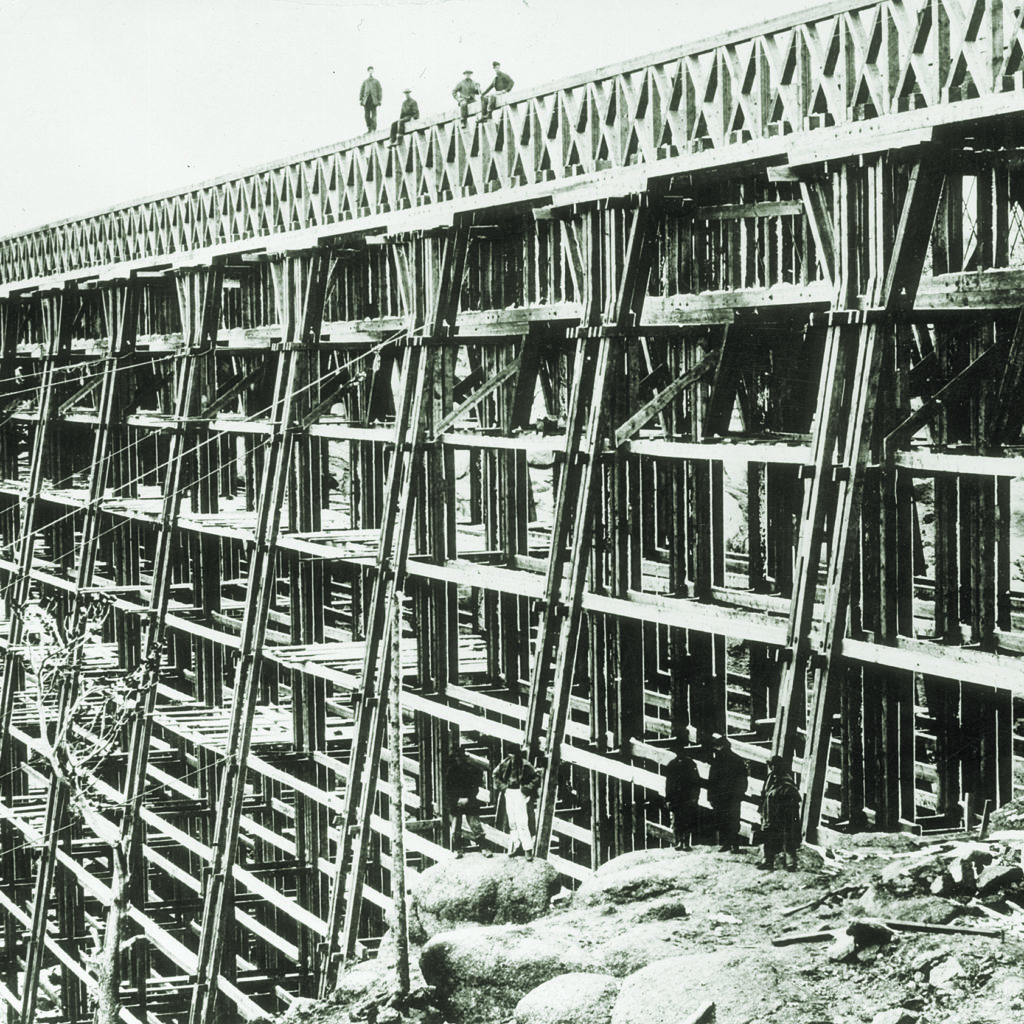

Garfield’s anxiety had its origins in the effort to construct a transcontinental railroad linking the country’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts. The visionary scheme aimed at establishing not only a passenger and freight transportation network but a grid of communities around which the nation could grow. Knowing the stakes and wanting to speed the project, Congress in 1862 passed the Pacific Railroad Act, authorizing issuance of generous land grants and government-backed bonds to the railroads. The companies building the rails, the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific, incurred huge expenses and took giant risks, hoping for enormous returns. No project in America’s preceding 90 years had been of remotely similar scope or significance. Nonetheless, the Union Pacific was having trouble drawing investors. Congress priced stocks and bonds such that it made the securities extremely tough to sell to Eastern speculators—until Union Pacific Vice President Thomas C. Durant devised a clever solution. Durant, who understood that the big money would come from building—not running—railroads, bought a dormant railroad finance company in 1864 and renamed it Credit Mobilier.

Durant used Credit Mobilier to soak the government-backed Union Pacific by overcharging the railroad for construction contracts. The company made millions of dollars in profits for its investors, a number of whom also sat on the Union Pacific board. A congressional committee that investigated the operations of Credit Mobilier concluded in 1873 that the company’s most lucrative contract with the Union Pacific produced almost $30 million in profits.

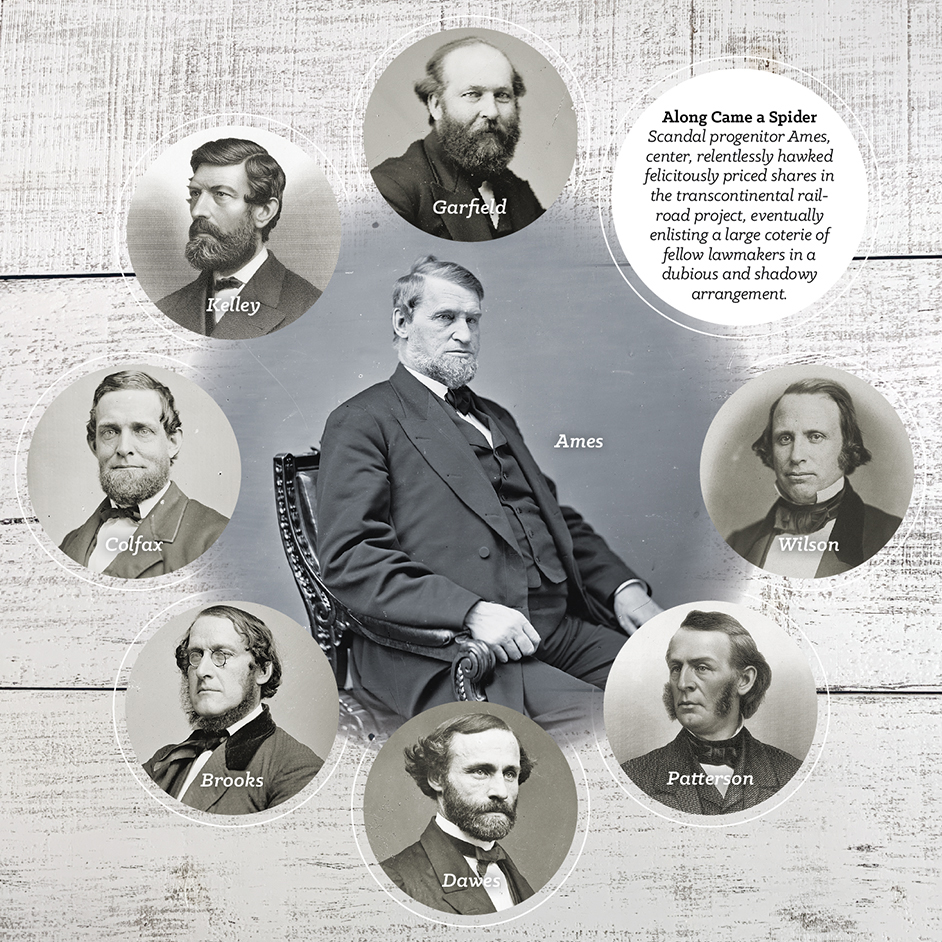

One of the most enthusiastic investors in the Union Pacific and in Credit Mobilier was U.S. Representative Oakes Ames (R-Massachusetts), whose family-owned shovel-making business had earned him the sobriquet “King of Spades.” After Ames and Durant—both Credit Mobilier board members—patched up a bitter feud over control of the railroad in the fall of 1867, they divided control of unallocated Credit Mobilier shares between them.

But another investor, Henry S. McComb, a railroad speculator and Durant ally, insisted that he should have received some of the extra stock as well. McComb pressed Ames to accommodate him. The King of Spades refused. Ames told McComb by letter that he was offering the shares in question to members of Congress as a way to win the Union Pacific support on Capitol Hill. “I have used this,” Ames said of the Credit Mobilier stock, “where it will produce most good for us, I think.” McComb was unconvinced. In November 1868, he sued Ames and Credit Mobilier demanding more shares.

A mes’s dual role as a member of Congress and major investor in the Union Pacific troubled some. “This man, worth millions, takes the position of Representative—seeks and gets it—for the purpose of promoting his private interest,” Navy Secretary Gideon Welles raged in his diary. But many in Congress were eager to do business with the King of Spades. As the feud with McComb was simmering during the winter of 1867-68, Ames was flogging the valuable Credit Mobilier shares to Capitol Hill colleagues wherever he caught them—on the floors of the House and the Senate, over dinner, and on the streets of the capital. Ames buttonholed Representative William “Pig Iron” Kelley (R-Pennsylvania) at a corner a few blocks from the White House. Kelley recalled Ames offering shares on terms so generous “I did not see how I could lose anything.” Garfield hesitated, but Ames kept pressing him. “He said if I was not able to pay for it, he would hold it for me `til I could pay, or until some of the dividends were payable,” Garfield testified. Ames eventually persuaded Garfield to accept 10 shares on those terms, investigators concluded, and recruited at least 10 other Hill colleagues willing to invest.

mes’s dual role as a member of Congress and major investor in the Union Pacific troubled some. “This man, worth millions, takes the position of Representative—seeks and gets it—for the purpose of promoting his private interest,” Navy Secretary Gideon Welles raged in his diary. But many in Congress were eager to do business with the King of Spades. As the feud with McComb was simmering during the winter of 1867-68, Ames was flogging the valuable Credit Mobilier shares to Capitol Hill colleagues wherever he caught them—on the floors of the House and the Senate, over dinner, and on the streets of the capital. Ames buttonholed Representative William “Pig Iron” Kelley (R-Pennsylvania) at a corner a few blocks from the White House. Kelley recalled Ames offering shares on terms so generous “I did not see how I could lose anything.” Garfield hesitated, but Ames kept pressing him. “He said if I was not able to pay for it, he would hold it for me `til I could pay, or until some of the dividends were payable,” Garfield testified. Ames eventually persuaded Garfield to accept 10 shares on those terms, investigators concluded, and recruited at least 10 other Hill colleagues willing to invest.

At least one went to bat for Ames. Representative Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts bought 10 Credit Mobilier shares for $1,000 in December 1867. Dawes then shepherded into law a bill authorizing the Union Pacific to move its headquarters away from New York—and beyond the reach of judges allied with Durant. Although the railroad failed to take advantage of the opportunity to relocate, the measure illustrates what Ames was hoping to get for his stock.

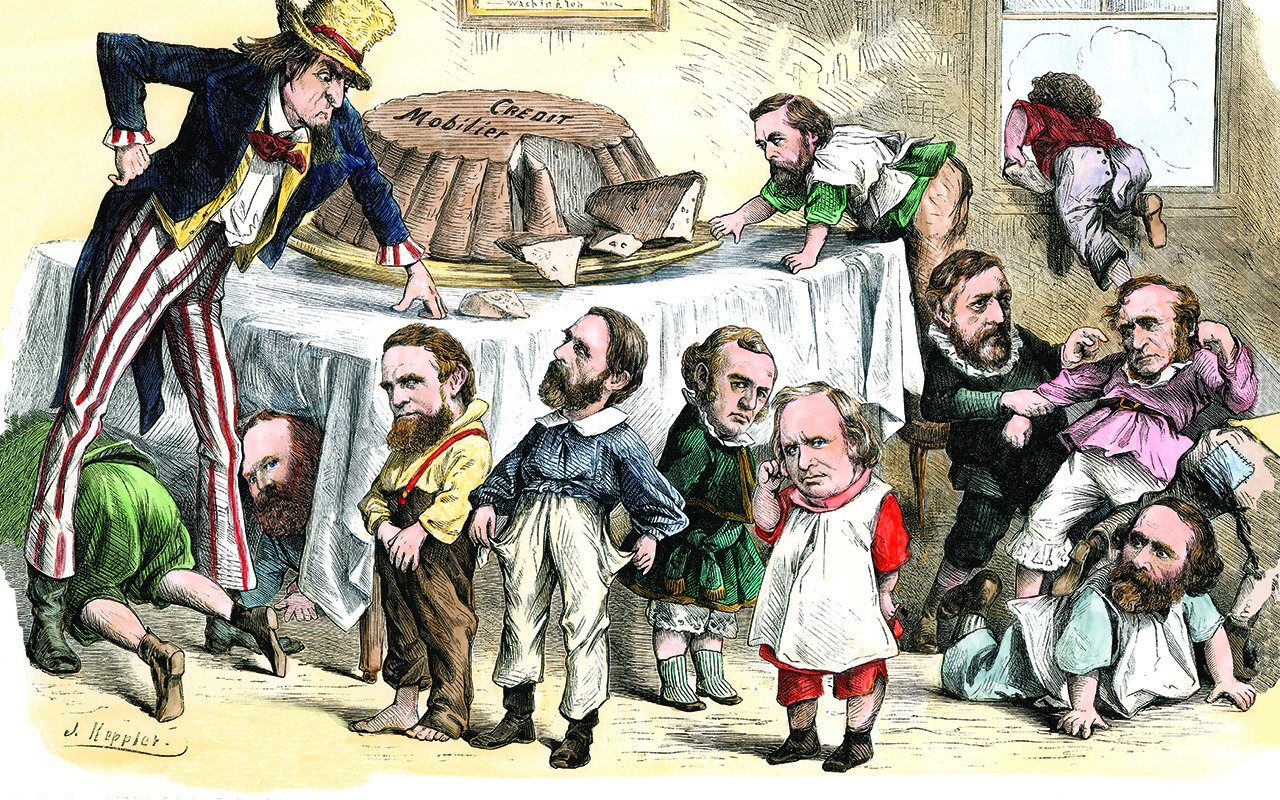

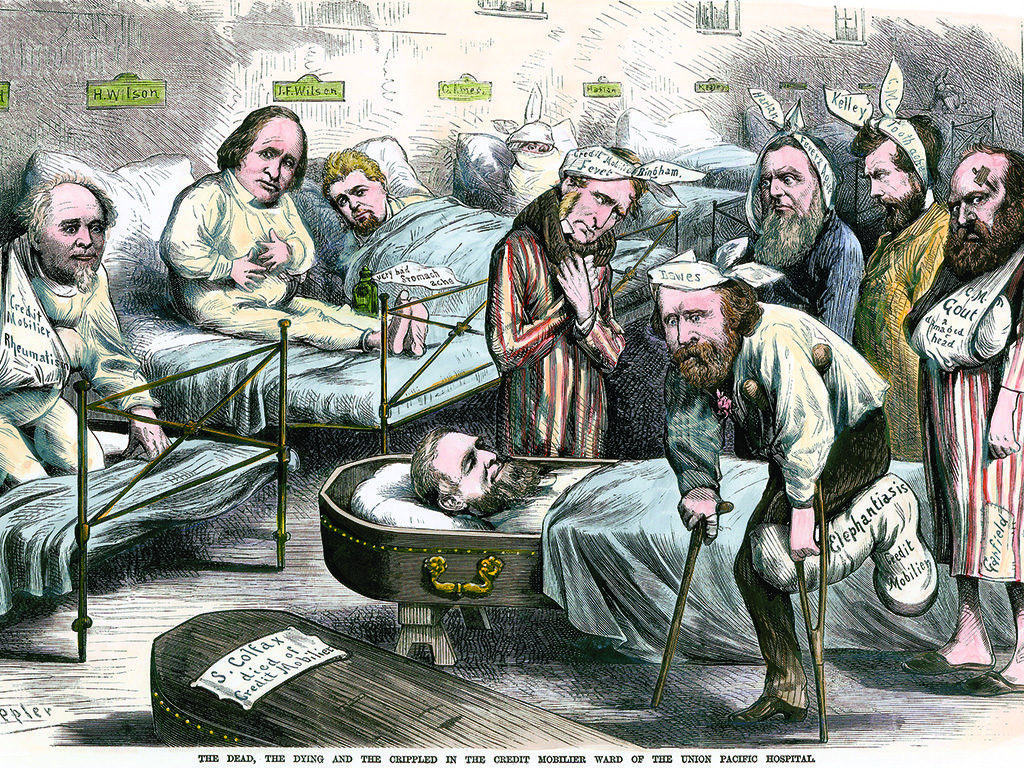

Credit Mobilier’s reach into Congress did not go unnoticed. In 1869, railroad finance expert Charles Francis Adams Jr., descended from two presidents, warned in an article in the North American Review that Credit Mobilier represented “a source of corruption in the politics of the land, and a resistless power in its legislature.” Americans paid little heed until September 4, 1872, when the muckraking New York Sun devoted most of its four broadsheet pages to an article headlined “The King of Frauds” detailing what McComb had said when testifying against Ames in his suit. Error-ridden and slanted—one subtitle read “Congressmen Who Have Robbed the People, and Who Now Support the National Robber”—the newspaper’s exposé nonetheless spelled out the fundamental facts.

In his lawsuit, McComb named 11 congressmen Ames had identified to him as recipients of Credit Mobilier shares in 1867-68. Along with Garfield, McComb listed former House speaker Schuyler Colfax, now vice president, and Senator Henry Wilson (R-Massachusetts), picked by President Ulysses S. Grant to replace Colfax on the ticket for his 1872 re-election run. Lesser figures named by the Sun included Senator James Patterson (R-New Hampshire) and U.S. Representative James Brooks (D-New York), who had bought Credit Mobilier stock independently of Ames. The Sun also presented damning transcripts of letters that Ames had written to McComb in early 1868. In those missives, Ames confided that his decision to place the Credit Mobilier stock with congressional colleagues was an effort to amplify the Union Pacific’s sway on Capitol Hill. “We want more friends in this Congress,” Ames told McComb, “& if a man will look into the law, (& it is difficult to get them to do so unless they have an interest to do so,) he cannot help being convinced that we should not be interfered with.”

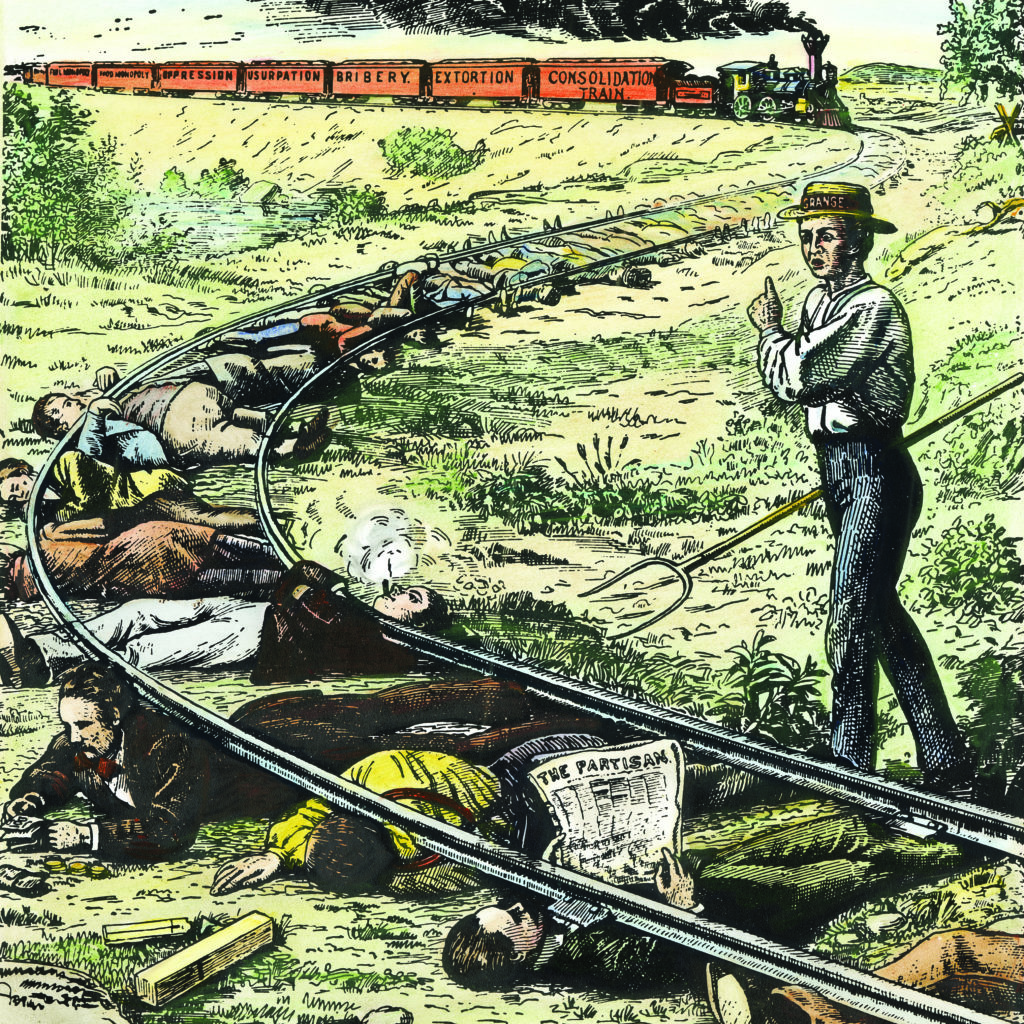

The sensational reporting galvanized readers. Southern and Northern Democrats, who were eager to undo Reconstruction, cited the stories as evidence of Republican corruption.

Conservative critics believed Credit Mobilier exemplified the dangers of government involvement in business. The exposé also spoke to growing concern about the way railroads were transforming the nation’s economy.

Americans celebrated the completion of the transcontinental connection in 1869, but their enthusiasm curdled as railroads flaunted their domination of state legislatures from Albany to Sacramento. Farmers in the Mississippi Valley and the South, angry about extortionate freight rates and monopoly power, flocked to the nominally apolitical Patrons of Husbandry—also known as the Grange—to counter railroad influence. Newspapers nationwide ran stories inspired by the Sun scoop. The once obscure phrase “Credit Mobilier” quickly became shorthand for the assumption that railroads were corrupting American politics.

The Sun blockbuster exploded as Garfield was out in the Montana Territory, concluding a visit with the Flathead Indians. The Ohioan devoted September 8 to catching up with his mail and the news. Garfield had every reason to look forward to his return to Washington. With Grant poised to crush the quixotic editor-turned-politician Horace Greeley in the November election, many more years of Republican dominance seemed assured. Garfield’s political ascent, which had begun with his 1859 election to the State Senate and to Congress in 1862—with time off during the Civil War to lead Ohio troops as a Union general—showed no signs of slowing. Back East, he would be resuming his duties as chairman of the powerful House Appropriations Committee and a political partnership with House Speaker James G. Blaine. A rude shock greeted him, however, in the form of newspaper stories and headlines screaming about Credit Mobilier. As he was on his way home, Garfield struggled to grasp his circumstances. “I find my own name dragged into some story which I do not understand but see only referred to in the newspapers,” he confided in his diary on September 9. As his train was nearing Ohio, Garfield dashed off a note to Colfax inquiring “about the nature of the slander against him and me and others.” Responding by mail, Colfax professed indifference to the revelations, but the vice president later made an emotional denial before a hometown crowd in South Bend, Indiana, that would be proven false. Back in Washington, Garfield turned for additional advice to a high-powered capital attorney. Pennsylvanian Jeremiah Sullivan Black, a Democrat, had been a state judge and attorney general and secretary of state during the Buchanan administration. If anyone could erase Garfield’s uncertainties, it was this consummate Washington insider, to whom Garfield referred as “a great and delightful friend.”

Black may have been a treasured confidant, but he was not a disinterested observer. He had represented McComb in his suit against Ames and had tipped a Washington correspondent for the Sun to McComb’s testimony. Seeking counsel on how best to respond to the Credit Mobilier revelations, Garfield was relying on the man responsible for leaking them.

Black assured Garfield that all was well. Ames was guilty of offering a bribe, Black advised, but because Garfield had not known bribery to be Ames’s purpose, Garfield was not guilty of accepting a payoff. Garfield should remain calm and profess ignorance about Ames’s intentions, Black said, adding that this stance “shows that you were not the instrument of his corruption, but the victim of his deception.”

Placated, Garfield met with Blaine in early December to plan an investigation into the Sun allegations. The next day, the House formed a committee of two regular Republicans, one Liberal Republican, and two Democrats, to look into the charges. U.S. Representative Luke Potter Poland (R-Vermont), headed the panel. At first meeting in secret, the committee took testimony from Ames and McComb. When protests by the press and the public forced the proceedings into the open, members and former members of Congress trooped into the committee room to tell their sides. Most denied buying shares or claimed to have backed out of deals shortly after purchasing shares. Ames insisted that there was nothing wrong with a member of Congress holding stock in a corporation that could be affected by the legislation of Congress. The Sun wryly headlined a series of stories on the hearings “Trial of the Innocents.”

With the press and Capitol Hill fixated on the scandal, Garfield found staying as cool as Black had advised easier said than done. As the day of his testimony was approaching, Garfield battled a nausea-inducing bout with nerves. The House floor, usually a refuge where lawmakers could immerse themselves in legislative debate or gossip, offered no relief. Garfield felt the House to be consumed by a “feeling of panic” caused by the continuing “discussion of the Credit Mobilier and the Pacific R.R,” he wrote in his diary. On January 14, Garfield testified as Black had counseled. He admitted under oath that he had discussed purchasing Credit Mobilier stock with Ames but said he never actually agreed to buy shares—and claimed not to have known at the time what exactly Credit Mobilier did. “You never examined the charter of the Credit Mobilier to see what were its objects?” committee member George McCrary (R-Iowa) asked.

“No sir,” Garfield replied. “I never saw it.” He was under the impression, Garfield maintained, that the company built housing.

“You did not know that the object was to build the Union Pacific Railroad?”

“No sir,” Garfield said. “I did not.”

Garfield’s denial echoed similar dodges by Colfax, Kelley, Patterson, Wilson, and others. The evasions infuriated the King of Spades. As congressmen who had bought stock from Ames were trying to put as much distance between themselves and Credit Mobilier as possible, the Massachusetts Republican again addressed the investigative committee. He explained in detail his transactions with members of the House and Senate. Patterson, the Republican senator from New Hampshire, was Ames’s first target.

Having once denied to the committee that he had bought Credit Mobilier shares from Ames, former schoolteacher Patterson returned to admit under oath that he had bought the shares. Ames looked on as Patterson squirmed “like one of the poor delinquents he used to torture” in the classroom, the Sun reported.

The next day, Ames elaborated, testifying that many lawmakers had held shares far longer than claimed and as a result had reaped substantial dividends. Ames’s revelations enraged James Garfield. The King of Spades “is evidently determined to drag down as many men with him as possible,” Garfield steamed in his diary on January 22. “How far he will be successful it remains to be seen. But in the present condition of the public mind, he will probably succeed in throwing a cloud over the good name of many people. He seems to me as bad a man as can well be.”

As fellow lawmakers were trying without success to clear their names, Garfield swung between optimism and despair. On February 8, he wrote a friend in Ohio that “men here are recovering their balance a little and begin to think with more calmness on the merits of the case” but stopped short of forecasting an end to his troubles. It was “too early,” Garfield cautioned his correspondent, “to tell into what conclusions the public judgment” would be. Writing in his diary a day later after dining with Black, he struck a gloomier note, dismissing the other man’s sunny predictions. Garfield said he doubted Black saw “all the forces that are now at work to injure and defame.”

Weeks of tension climaxed on February 18, 1873, with release of the Poland committee report. That body’s findings and recommendations resounded through the House chamber for about an hour as the House clerk read the document aloud and implicated lawmakers grimaced and glared. “The report produced a profound sensation and was listened to with silence and painful interest,” Garfield wrote in his diary. Garfield pursed his lips and avoided eye contact as the clerk read a committee finding that he had bought 10 shares from Ames and received $329—$8,060 today—in dividends. The committee concluded that virtually every individual on the roster McComb’s provided had made money on Credit Mobilier shares sold by Ames. Poland demanded that the House expel Ames and Brooks.

Despite the committee’s findings, Garfield felt vindicated. In an outcome that infuriated Democrats and the public, the committee concluded that Ames had been attempting to use Credit Mobilier stock to sway lawmakers’ votes—but also that Garfield and others who bought the stock were innocent of wrongdoing. The Poland committee could not “find that any of these members of Congress have been affected in their official action in consequence of their interest in Credit Mobilier stock.” Black, the influential capital insider who distinguished between offering and receiving a bribe, had been right.

But if Garfield thought the worst was past, he was badly mistaken. The Senate failed to vote on the expulsion of Patterson recommended by the Senate committee examining the scandal. Public fury intensified when, just before leaving town, Congress voted itself a retroactive pay increase—accomplished by attaching the bump up to an appropriations bill that Garfield had managed.

On top of everything else, the aftershocks of the Panic of 1873, an economic plunge which triggered the worst economic crisis in American history until the Great Depression of the 1930s, intensified the ensuing political crisis.

Garfield responded with dispatch. He quickly refunded his own raise, a gesture that the local press applauded. He published a paper defending himself against the Credit Mobilier allegations and he campaigned energetically across his district. These efforts helped fend off disaster, but Garfield also benefited from a divided opposition that fielded two candidates—a Democrat and an Independent who had been nominated by Garfield’s Republican foes.

Democratic attempts to link Garfield to a paving contract scandal in Washington, DC, went nowhere. Garfield hung on to win re-election in 1874 even as Republicans lost dominance of the House for the first time since 1858.

His escape accelerated Garfield’s rise through Republican ranks. When Blaine went to the Senate in 1876, Garfield became House Republican leader. In 1880, divided Republicans turned to Garfield over Grant and Blaine as their presidential nominee (“Porch Politics,” August 2016).

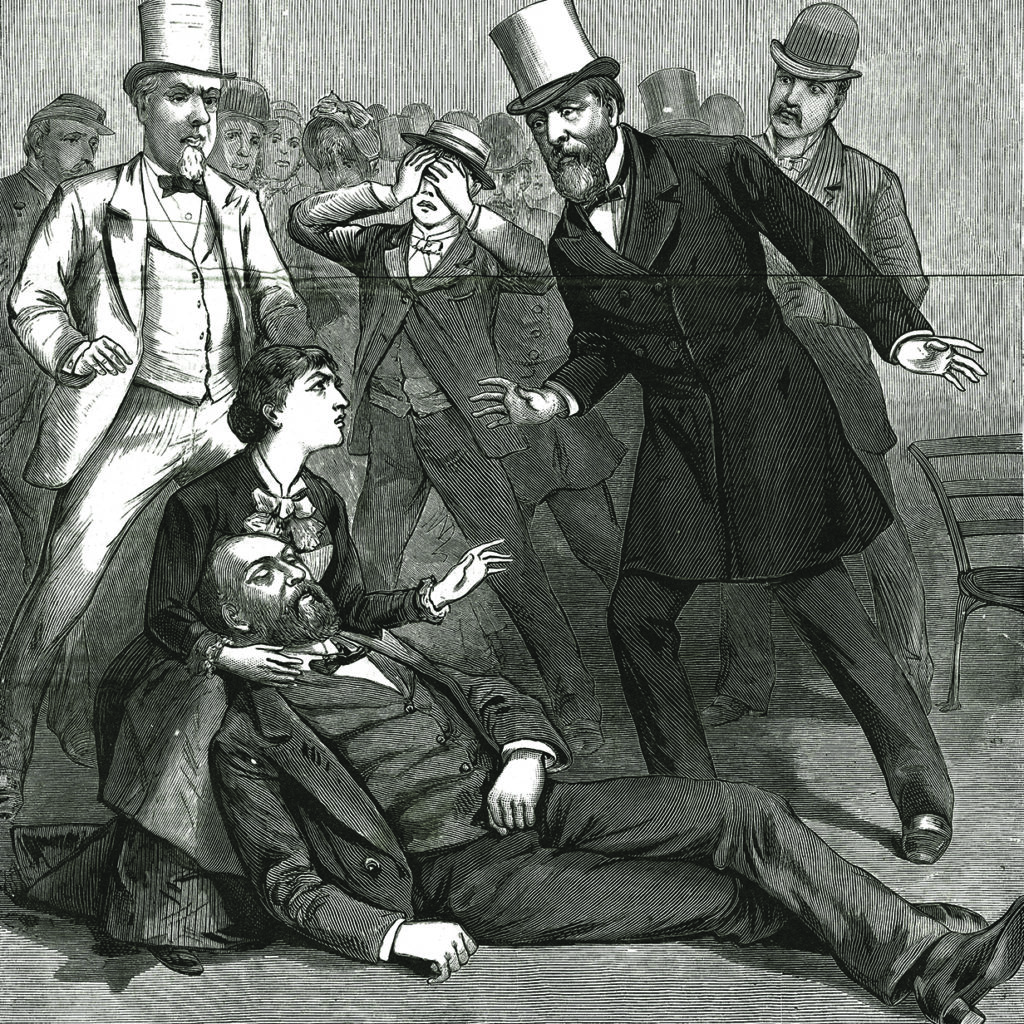

As Garfield had feared, the specter of Credit Mobilier lingered. During the 1880 campaign Democrats made the scandalous affair a rallying cry. “Are honest men willing to put at the head of the most important nation on the globe a man whose oath has been squarely contradicted as was Gen. Garfield’s oath in the Credit Mobilier report?” the Democratic Washington Post asked. The answer was yes—barely. Garfield’s 59-vote Electoral College win masked a razor-thin 8,355-vote popular margin over Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock. On July 2, 1881, the president was waiting to board a train in Washington when a delusional man ritually characterized as a “disgruntled officer-seeker” shot and badly wounded him. Garfield died September 19 from infections caused by doctors’ unsanitary handling of his injuries.

Historians convinced that intraparty feuding consumed Garfield’s presidency damn him with faint praise. “His stormy presidency was brief, and in some respects unfortunate, but he did leave the office stronger than when he found it,” biographer Allan Peskin wrote in 1978. Just after his death, though, the once-jaundiced Post was more effusive. “The events of his wonderful life, supplemented by the sad dramatic incidents of the past two and half months, will make such chapters of history as will be read with ever-increasing interest for centuries to come.” The paper made no mention of Credit Mobilier or Garfield’s hand in the scandal that less than a decade earlier rocked the capital. The “shadow of the cursed thing” had lifted, at last.

______

A Credit Mobilier Primer

In passing the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, Congress intended to promote construction of the transcontinental railroad with $48,000 in governmentbacked bonds and 6,400 acres in land grants for every mile of track laid. Despite the proffered federal largesse, investors stayed away because the law barred the railroad from selling its securities at less than face value and put investors on the hook should the venture fail. In addition, the railroad was to be built across the vast expanse of the West to serve markets and communities that did not yet exist.

By 1864, the Union Pacific needed to raise capital—and fast—or construction of the transcontinental line would stall.

Swashbuckling Union Pacific Vice President Thomas C. Durant, nicknamed “the Napoleon of Railways,” improvised a solution. Durant bought a Pennsylvania-chartered construction company he rechristened “Credit Mobilier,” borrowing a prominent French bank’s glamorous name. Durant used Credit Mobilier to build his railroad. More importantly, Credit Mobilier could generate profits for itself and dividends for Union Pacific stockholders by inflating construction costs and taking payment in Union Pacific securities.

Unlike the railroad, Credit Mobilier, upon receiving Union Pacific shares in payment, could resell those shares at the market price rather than the rate Congresshad set. And customers who obtained Union Pacific stock through Credit Mobilier avoided the liability hanging over those who invested directly in the railroad.

Durant’s arrangement allowed investors to pay themselves to build the Union Pacific, an arrangement commonly used by other railroads that in this instance raised questions about whether the government was being fleeced.

Representative Oakes Ames (R-Massachusetts), an avid railroad investor, believed Credit Mobilier offered a “practical scheme” for profitably investing in the Union Pacific. He poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into the venture and recruited fellow New Englanders to invest before falling out with Durant in a battle for control of the Union Pacific and its lucrative construction subsidiary. In autumn 1867, as Ames and Durant resolved their differences, they divided unallocated Credit Mobilier shares and formalized a $48 million construction contract with the railroad. A congressional committee found that Credit Mobilier billed the railroad $57.1 million for construction when the actual cost was $27.1 million, producing a profit of almost $30 million—$513 million today. The lucrative pact made Credit Mobilier shares much more valuable—one investor estimated that the stock doubled in value as a result—just as Ames began to peddle them on Capitol Hill. —Robert B. Mitchell

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age by Robert B Mitchell, Edinborough Press, 2017; $22.95