Ever since 1968, I have been meaning to compose a letter to the Godfather of Soul that begins something like this:

Dear Mr. James Brown,

First, I want to thank you for coming to Vietnam and performing for the soldiers at Long Binh. Second, I want to apologize for the racist behavior of Eddie and Jerry. I should have known better than to bring them along.

But, now that the hardest-working man in show business is gone, I am writing this confession instead.

Few of the obituaries I have read mention James Brown’s visit to Vietnam in June of 1968, a scant two months after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Not only were cities in America erupting in flames, racial tensions were running high in the combat zone. At the time, I was a human target stationed at a small outpost near Bien Hoa called the Train Compound. The Air Force personnel assigned there were part of the 12th Combat Support Group, which directed airstrikes throughout III Corps. I was a radio operator, and my job was to transmit and receive information between ground units and forward air controllers who directed these strikes. One of the great ironies of this situation is that Eddie and Jerry were part of our “intelligence unit.”

It was such a great morale booster when celebrities came to Vietnam, we all came unglued. In the movie Apocalypse Now, there is that hilarious and frightening scene when the Playboy bunnies copter in to perform in front of 1,000 fired-up soldiers. At Train Compound, we never drew any Playmates, but I do remember Donna Douglas of The Beverly Hillbillies showing up. To my great consternation, I was pulling a shift at the communications post and missed her. The performer most famous for visiting war zones, of course, was the legendary Bob Hope, who entertained three generations of soldiers from World War II to the Gulf War. While I was stationed in Vietnam, he visited Cam Ranh Bay. Because he was considered a national treasure, he arrived under heavy security and his performance was announced only three hours before his plane touched down on the tarmac.

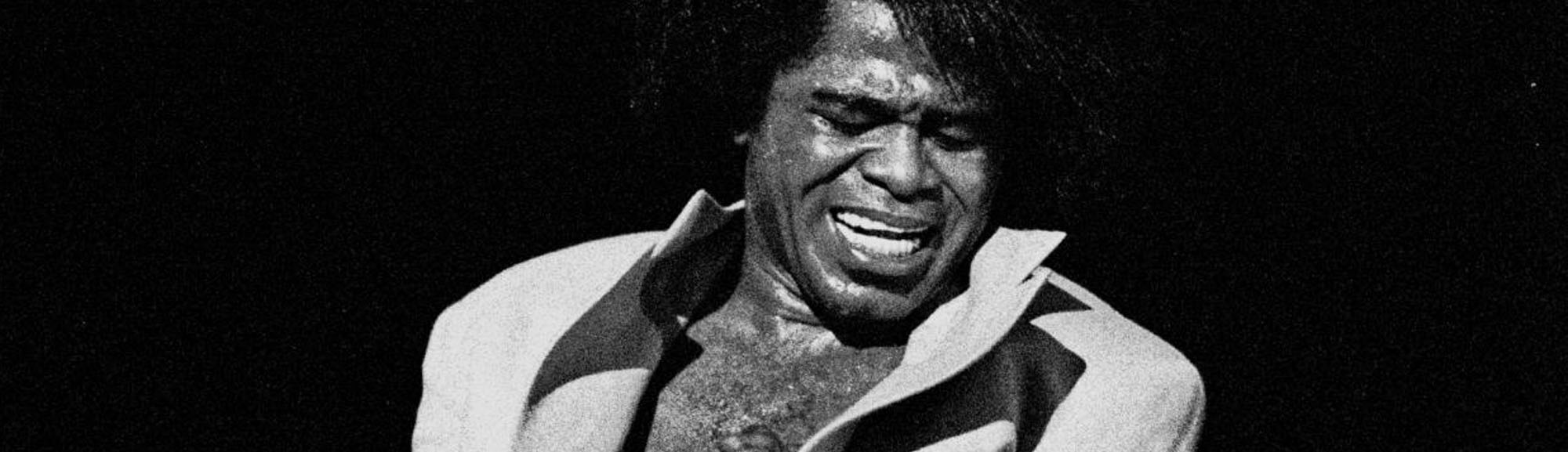

On the other hand, James Brown’s arrival was anything but top secret. Two weeks before his scheduled appearance in Long Binh, I was wheeling and dealing in an effort to swap shifts with the other radio operators. Why would a white kid who grew up in a Puget Sound town equivalent to Norway be so eager to see the Godfather of Soul? I had caught his act in a movie entitled The T.A.M.I. Show at the Autoview Drive-In Theatre. Hosted by Jan and Dean, the movie featured performances by ’60s superstars such as Marvin Gaye, Chuck Berry and The Rolling Stones. James Brown and the Fabulous Flames stole the show. My drunken friends and I suspended our laughing and partying during Brown’s performance of “Please, Please, Please” because we had never seen or heard anything like that in our lives. The man was in agony, every ounce of his soul screaming for mercy until, finally, he collapsed to his knees, barely able to draw another breath. A couple of Flames draped a cloak over his shoulders and attempted to help him away, presumably taking him to the emergency ward. Then, suddenly, James Brown tossed off the cloak. He was singing again, agonizing about lost love until he fell to his knees once more. Again the Flames draped a cloak over him and again, James Brown broke free. After three or four “near-death” experiences, the song ended and at least one white boy from Gig Harbor, Washington, came to understand the meaning of soul.

Yes, I was hooked on James Brown, and I needed another fix. Arranging a ride to Long Binh, however, proved difficult. I discovered there would be a convoy headed past there on its way to Nha Trang, but how was I going to make the return trip a few hours later? Catching a bus was out of the question. Soldiers who waited at bus stops were easy pickings for motorcycle-riding VC who could toss a satchel charge and be gone before anyone knew what hit them. Besides, a knife attack I had suffered after boarding a Lambretta really soured me against public transportation. And, in a month I was due to ship out and return to The World. Time to minimize risks. Clearly, I needed to find someone with access to a jeep. Our Intelligence Unit had one.

When I explained to Eddie and Jerry that I needed a ride to see James Brown perform, they laughed in my face and entertained one another with “Liza and Rastus” jokes. I had already canvassed every enlisted man I could find who had access to a jeep and these two rednecks from the Deep South were my final option. Of course, they had no interest in seeing James Brown perform. I might as well have asked them to join me on a trip to Mars. However, the Intelligence jeep needed a back seat, which had been destroyed during a recent mortar attack. I told them to get their tools together. While everyone was listening to the concert, they could easily scavenge a new seat from any of the dozens of jeeps that would make the sojourn to Long Binh. We struck a deal.

The ride to Long Binh was bumpy and, as always, fraught with risk. An ambush was always possible, particularly driving through a hamlet like Tan Hiep or cruising past a patch of jungle. I had the honor of sitting in the seatless back throughout the half-hour journey. The bad news: uncomfortable. The good news: I could not hear a word Eddie and Jerry were saying. I liked them better that way.

When we reached our destination, their eyes lit up at the sight of so many unattended jeeps. Once the deed was done, they informed me, we were going to have to beat feet out of there. They promised to alert me when it was time to leave. I asked how they were going to be able to find me among the hundreds of soldiers attending the show. They motioned at all the African Americans streaming toward the amphitheater and laughed.

Even if I had not been a James Brown fan, I would have admired him for coming into a war zone to see us, share his talent with us and make our lives more bearable. In doing so, he was putting his life on the line.

That afternoon in Long Binh, I did not expect James Brown to repeat his T.A.M.I. Show performance. The sun was white-hot and the humidity, as always, was capable of sapping a man’s will in less than no time. The amphitheater was carved out of a blood-colored hillside GIs referred to as “The Dirt Bowl.” The covered stage at the bottom faced the afternoon sun, absorbing more than its fair share of thermal units. Within seconds after James Brown took the stage, his face was shining with sweat. Halfway through his first number, his sequined blue jacket was soaked. Still, he sang and jumped and ran and danced, even performing the move called “The James Brown” as he shimmied from one end of the stage to the other. Every number brought down the house. I had never imagined such joy could exist in that mass grave known as The Nam. I am certain I was not the only soldier who was surprised to discover tears flowing down his cheeks.

Five songs into the concert, Eddie squatted next to my aisle seat and tapped my shoulder. I remember glancing up at him, wondering how he could ask me to leave a place full of so much life. The smirk punctuating his freckled face explained it all.

James Brown was in the middle of “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” as I dragged my way up the steps, stalling so I could hear the song all the way through and applaud him one last time. I could see Jerry waiting at the top of the Dirt Bowl, waving for us to hurry. Soon Eddie joined him, and both of them motioned for me to get a move on. “Di di mau, di di mau.” When I was a few steps from the top of the bowl Eddie leaned over and cupped a hand next to Jerry’s ear, telling him something. They smiled and exchanged glances, then laughed. The song wound down to its final notes, and during the brief gap before applause could commence, Eddie and Jerry cupped their hands around their mouths and shouted the word “N——!”

Even now, 39 years later, I can still remember how those two syllables resounded across that red-dirt amphitheater, assuming a life of their own as Eddie and Jerry ran laughing toward the parking area. I turned and faced the stage, my hands opening wide, palms beseeching. Hundreds of shocked and angry faces looked up at me, and although I desperately wanted to set the record straight, I knew the situation was impossible. In a moment, whatever explanation I might offer would likely be buried beneath a sea of anger.

I ran like hell, throwing myself into the newly acquired backseat of the jeep. I was so blinded by my own fear and shame, I do not know if anyone chased after us as we roared toward the main gate. What I knew with absolute certainty was that every single person in the Dirt Bowl believed I was the one who had shouted that dreadful word. These were all men who were sacrificing themselves day in and day out, and they had earned the right to never be disparaged for the color of their skin ever again in their lives. But looking back, I suppose there was an unintended lesson embedded in that ignorant statement delivered by Eddie and Jerry. Justice for many Americans, despite being earned, might never be won. Whatever anger was generated by that profanity may have prepared many of those men for the blunt truth they would face when they returned home.

As I recollect, Eddie and Jerry laughed all the way back to the Train Compound. I fumed in the backseat, calling them every name in the book. I remember asking them how they could use such a word when we depended on the Black men beside us for our very lives. I tried to tell them how we were all in the same boat, white, black, red, yellow and brown. But I just remember them laughing harder.

Eventually, I gave up ranting and lecturing these two budding Klan members. Instead I began to compose a letter in my mind, one that I never mustered the courage to write to James Brown. I would have begun by thanking him for giving so much of himself on that day at the Long Binh Dirt Bowl. I would then have tried to explain what happened and apologize for that terrible moment. I think part of the reason the letter never got written is that I could never find words that would truly make up for the wrong that had been done. Besides, if I possessed any integrity at all, I would have had to admit I was wrong to fraternize with the likes of Eddie and Jerry; that I, like too many white Americans, had tolerated racism.

When someone dies, all of us who love him are haunted by the things we should have done or should not have done; we feel guilt over words said or left unsaid. I am saddened beyond measure by James Brown’s passing on Christmas Day 2006, and because I never mustered the courage to write him, guilt will always taint my otherwise wonderful memories of this great performer. The only other thing I can think to do is offer this feeble explanation to the other men who were there that day, my brothers-in-arms. I offer this confession by way of apology. Although I may not deserve it, I beg their forgiveness.