The esteemed 20th-century writer demanded that White society accept its culpability in the betrayal of Black people

Eddie S. Glaude Jr., James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, is the author of Democracy in Black and Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and its Urgent Lessons for Our Own (Crown, 2020), an expression of anguish at American racial recidivism viewed through Baldwin’s life and works.

Why use James Baldwin’s writing to examine the precarious state of race in America? I have been reading and teaching Baldwin for more than 20 years. I think he is the most insightful writer we have ever produced on the vexing issue of race and democracy. His later works, especially No Name in the Street, revealed his struggles with the nation’s equal-rights betrayals. He desperately sought to pick up the pieces in the face of the country’s refusal to change; in the effort, his art and social criticism evolved. I found those works helpful in my effort to come to terms with my despair and disillusionment.

Initially Baldwin successfully wrote fiction but then racism really became a moral mission for him, didn’t it? Indeed. But I would argue that the moral issue of racism preoccupied him from the beginning. Baldwin grappled with, among other things, what gets in the way of an honest understanding of who we are and who we aspire to be. He explored ruthlessly our illusions of safety and comfort. And it is in this exploration of the perils of individual self-understanding—and the ongoing challenge of loving and being loved—that Baldwin makes the move, by analogy, to the broader question of the country’s moral state. Racism becomes one of the most important areas to explore, because it organizes so much of American life, and keeps us from confronting ourselves honestly.

Calling himself a “despairing witness,” Baldwin wrote that “America changes all the time without ever changing at all.” He uses the phrase “despairing witness” to describe his ongoing effort later in life to tell the truth about America, while many were leaving behind the tumult of the 1960s and 1970s for the comforts of the ’80s. He saw how and why the nation turned its back on the Black freedom struggle and yet still claimed that struggle as an example of American perfectionism. The story of the movement had become a part of the exceptional story of America. However, Baldwin also saw the depths of suffering in the nation and how the belief that White people mattered more than others continued to organize American life. This belief and the practices that give it meaning constitute the through-line of American history. It is, to invoke Amiri Baraka, “the changing same.”

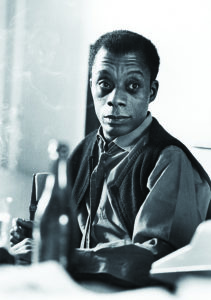

Baldwin didn’t have an easy life growing up in Harlem. Not at all. He was born in August 1924. He grew up in the heart of the Great Depression. He chronicles the difficulties his stepfather had in providing for his family of nine children. He was not a product of Sugar Hill. His class position informs and shapes how he sees the world.

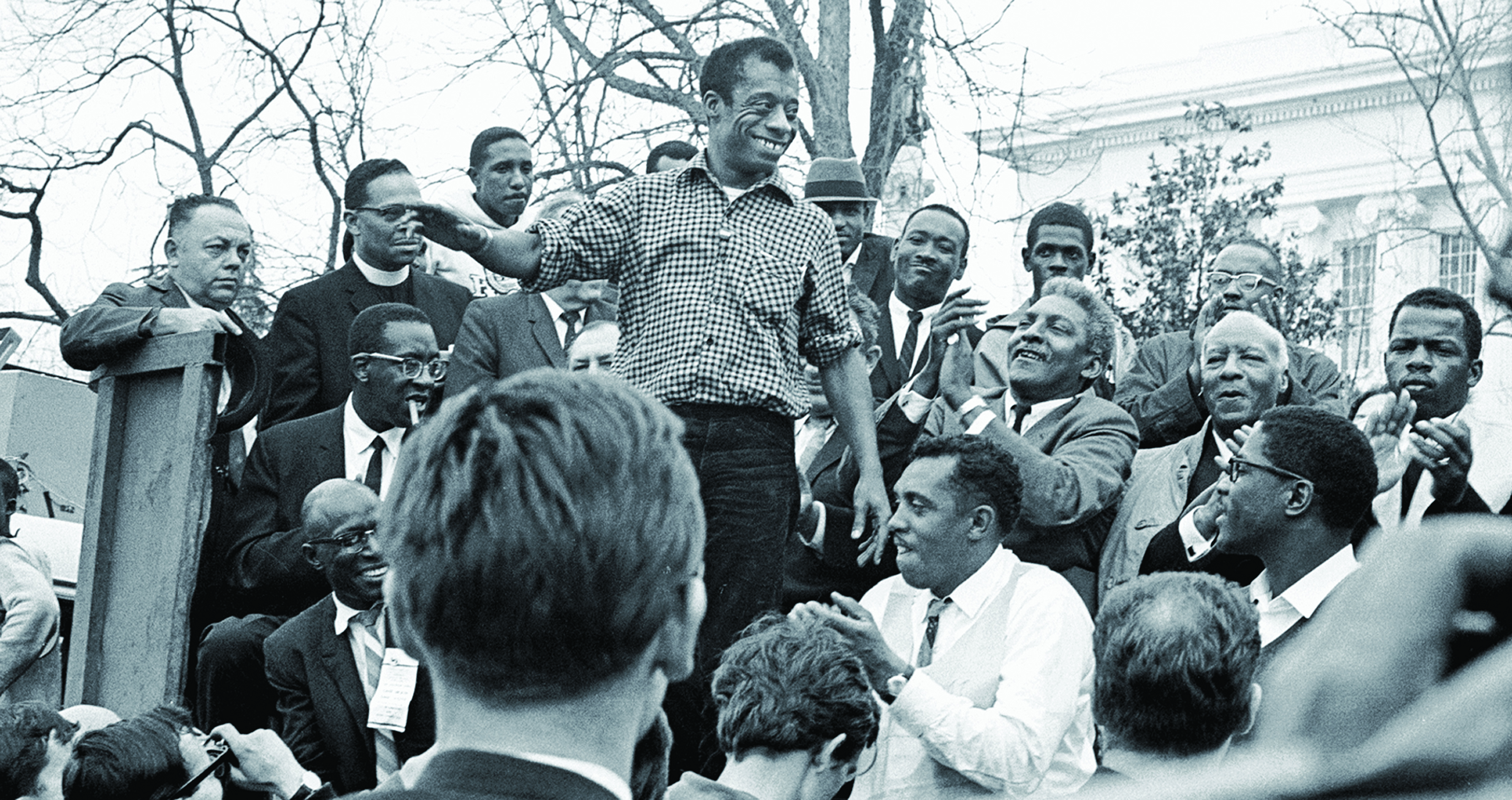

In the Civil Rights movement, was he caught between his peers Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X and younger revolutionaries like the Black Panthers? I don’t think so. His was a unique voice, the voice of an artist seeking to render what he witnessed—to tell the story of the extraordinary efforts of those he described as “improbable aristocrats.” In some ways, Baldwin “queers” Black politics. He complicates the hypermasculinity at its core and refuses the binaries that often shape our accounts of the moment. He loves and he rages. He gives voice to a kind of humanism and yet speaks forcefully out of the specificity of Black life.

In Begin Again, you focus on America’s “big lie.” What is that? The lie is this story we tell ourselves to avoid confronting who we really are and what we have done. It is our way of avoiding facing the truth about the nation’s unjust treatment of Black people in the name of the belief that White people matter more than others. The lie is a vast architecture of meanings that malforms events to fit the story of America’s innocence. And its effect is to distort American democracy. Think of the 1776 Commission Report, for example.

Baldwin felt betrayed by the election of Ronald Reagan—it confirmed for him that the Civil Rights movement had failed. You felt a similar shock at Donald Trump’s election. Was that the catalyst for Begin Again? Absolutely. I kept saying to myself: they have done it again; they’ve done it again. And I worried about all of those young people who organized and protested in the name of Black Lives Matter. I worried about how they would react to the fact that the country responded to their sacrifice by vomiting up Trump. It is with this sense of despair, disillusionment, and concern that I retreated to the “ruins” of Baldwin’s work. There I found Begin Again.

You write that “we have to allow the ‘innocent’ idea of White America to die. It is irredeemable.” Is that the heart of the matter? Yes. There is nothing redeemable about the idea that some people ought to be valued more than others because of their skin color. So much of American life has been made disastrously hideous because of this belief. If we can finally uproot it, we may yet have a chance.

What do you want people to remember about Baldwin and his work—and how hopeful or despairing are you that America can overcome its lingering race issue? Baldwin insists, with Socrates, that the unexamined life is not worth living. We have to plumb the depths of our sorrows, wounds, and fears if we are to live and love genuinely. That becomes the ground for the work we must all do if we are to step into a New Jerusalem—to bear witness to the suffering, so that it may end. Mine is a chastened hope when it comes to race in America. Human beings are what they are. As Baldwin put it, we are, at once, disasters and miracles. But if we show up in moments when history calls, we at least have a chance for a miracle. My hope remains in us. We will see what we do next.

This interview appeared in the April 2021 issue of American History,