Dressed in plain khaki, with an American flag patch on his right shoulder and no insignia on his left, the young officer stood knee-deep in the stream, enjoying the cool water that offset the heat of the midsummer day. Thrilled to have a chance to fish, he had almost forgotten he was behind German lines in France and that the year was 1944. Soon, he was fully absorbed in placing his flies, casting from right to left and letting each fly float downstream past the trout he could see darting this way and that below the surface.

He heard little apart from the sound of riffles running over the rocks—that is, until marching boots were about 40 yards away, behind him to his left. His heart beat faster when he saw that they belonged to members of a German patrol who were now looking down at him as they marched along a set of railroad tracks above the limestone bank. Without raising their voices or addressing him directly, the soldiers seemed to be bantering, probably about his skill as a fisherman. He prayed that he would not hook a fish before the enemy moved on; they would almost certainly stay for the spectacle and notice the flag on his shoulder as he worked his catch.

Mercifully, the fish ignored the lures and, after what seemed like an eternity but probably was only a minute or two, the Germans continued on their way. The officer was again alone. Trembling, he forced himself to collect his gear and make his way onto the right bank, quickly putting as much distance as he could between himself and the railroad tracks.

THIS SCENE COULD BE FROM one of Ernest Hemingway’s many novels or short stories that mixed war and outdoor pursuits, especially hunting and fishing. In “Big Two-Hearted River,” to name but one example, Nick Adams retreats to a river on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to overcome wartime trauma by fishing methodically—just as the young officer takes leave from war by fishing. But this episode is not fiction. It is taken from the memoirs of Hemingway’s son, John Hadley Nicanor Hemingway, known as “Jack,” and bolstered by his father’s wartime letters and once-secret official files.

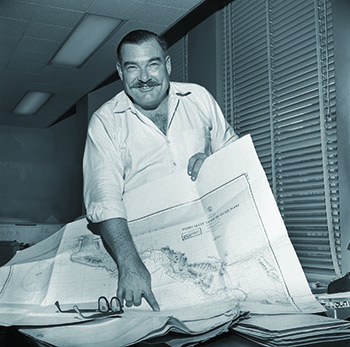

These sources show how Jack proved himself, again and again, under great pressure on the battlefield. Yet he has been overshadowed by his father’s tumultuous life and the characters he created: Adams; Frederic Henry, an American in the Italian army in 1917 trying to escape to neutral Switzerland in A Farewell to Arms; Robert Jordan of For Whom the Bell Tolls, an American guerrilla in a lonely war against Fascism in Spain in the 1930s. But Jack, as a member of the special operations branch of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), lived a wartime life of danger, excitement, and duty as fully as Henry or Jordan—and arguably more fully than his father, who hunted U-boats from his cabin cruiser off the coast of Cuba in the war’s early days, and was a cross between a freebooter and a war correspondent in France after D-Day.

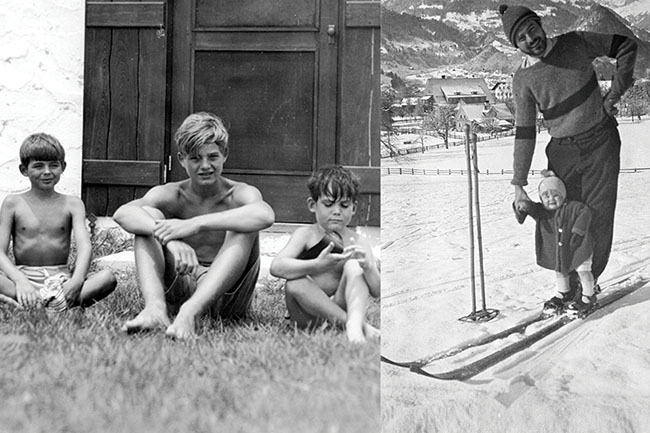

Born in 1923 to Ernest and the first of his four wives, Hadley, Jack is familiar to most Hemingway aficionados as the easygoing infant “Mr. Bumby” from his father’s memoir of life in Paris in the 1920s, A Moveable Feast. Young Jack was equally at home “in his tall cage bed with his big, wonderful cat named F. Puss” and on sleigh rides in the company of “a very dark-haired beautiful girl” named Tiddy at the Schruns, Austria, ski resort the family visited in 1926.

After Ernest and Hadley separated, Jack continued to live in Paris with his mother, becoming something of a Francophile with a firm grasp of the language and a fondness for the country. As Ernest’s son, Jack could not help also becoming an outdoorsman, with strong interests in hunting and, above all, fishing. He was a fit young man, with the best of his attractive parents’ good looks. Hemingway’s third wife, novelist and journalist Martha Gellhorn, wrote that at 16, the fair-haired Jack had “a body like something the Greeks wished for, and to make you cry it is so lovely.” He never has any problems, she continued, “because he never thinks about himself, but only about trout fishing.”

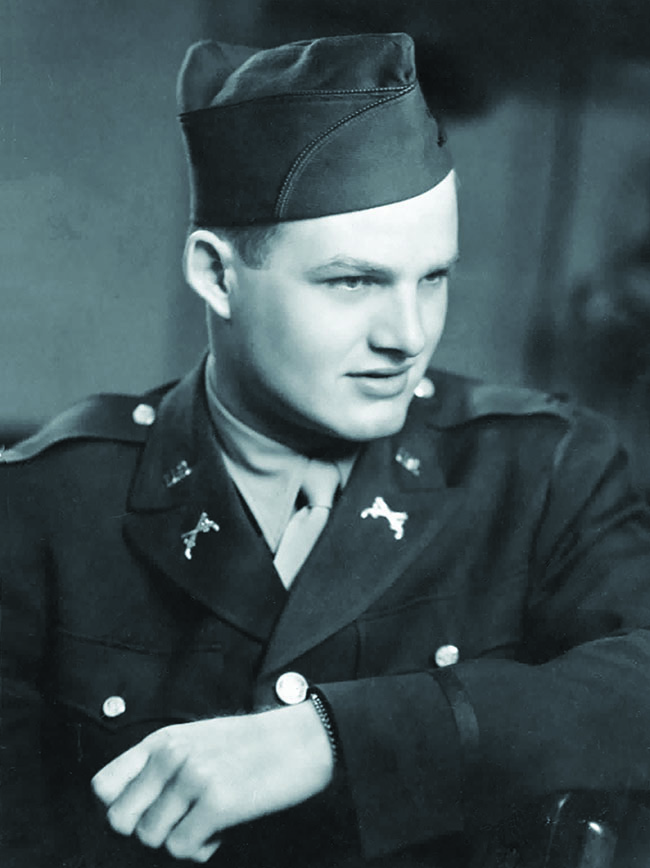

WHEN THE JAPANESE ATTACKED Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Jack, then 18, was living in Chicago with Hadley and her second husband, journalist Paul Mowrer. Wanting to live up to his father’s expectations, Jack decided to enlist in the Marine Corps. But both the senior Hemingway and the Mowrers counseled him against that. The war was likely to last for some time, they told him; if he had some college, he might become an officer and, with luck, help liberate the country he loved almost as much as his own. Jack entered Dartmouth College, where he took a course in military French, but dropped out a year later to join the army. Inducted in February 1943, he received no special treatment as the son of a famous author. The luck of the draw put him on track to become a second lieutenant in the military police (MP) branch.

Once commissioned, he set sail with his platoon of African American MPs for North Africa, arriving in Algeria in early 1944 and settling into a less-than-glamorous routine of guarding American installations well away from the front. Not long after, Gellhorn passed through on her way to report on the war in Europe. She arranged for Jack to meet her at the temporary home of her friends Duff and Diana Cooper, glamorous members of the British ruling class overseas on diplomatic assignment. Among the other guests was Winston Churchill’s often-troublesome son Randolph, 33, who had managed to work himself deep into the world of British special operations, roaming the deserts of North Africa and parachuting into occupied Yugoslavia. Jack listened to Randolph’s stories of derring-do with awe, and resolved to find the American equivalent of British special forces.

He stumbled upon it by following his nose. He discovered a nearby camp known for the remarkable food served in its mess, which was run by a French chef rather than a U.S. Army cook. Jack jokingly asked what he had to do to get into the unit. The answer was: if you can teach tactics in French and are willing to accept hazardous assignments, all you have to do is volunteer. And so Jack found himself requesting a transfer to this mysterious unit, the 2677th OSS Regiment (Provisional). Only after he had begun the process of joining did he learn what the regiment’s initials stood for. On July 5, 1944, Jack was officially seconded to the Office of Special Services, the home of American special operations.

BY THEN, D-DAY, the invasion of Normandy, was past. It was one of the key turning points in a long war and put Eisenhower’s forces on the road to Paris. But Normandy was hundreds of miles to the north; it was the looming invasion of southern France, code-named “Dragoon,” that was personal to soldiers in North Africa. Conventional units, many of them from bases in Algeria and Tunisia, would make the landings on the Mediterranean coast of France and fight their way north. OSS detachments from Algeria would support Dragoon by operating behind German lines even before the landings.

Jack learned this in a roundabout way when he was asked to replace an officer on a team of four—two American officers and two French radio operators—that would parachute a few miles inland from the southern coast in Hérault with two overlapping missions: scout a possible invasion route west of the Rhône River, and work with the French Resistance. The other officer, a down-to-earth man named Jim Russell, already had three combat missions to his credit. Jack, on the other hand, had not ever used a parachute. But he did speak French.

Given Jack’s eagerness, the 2677th decided that he would forgo jump training before the mission. Why risk an injury in training? His first jump would be a combat jump—something well-nigh unimaginable in today’s safety-conscious military. Jack added an unofficial Hemingway touch: he would jump into France with a fly-fishing rod in his right hand, along with gold Louis d’or coins sewn into his clothing, a compass and map case filled with trout flies, and an impressive assortment of weapons—a pistol, knife, and Thompson submachine gun.

It was on a clear, moonless night in mid-August 1944 that the crew of a B-17 bomber opened a hole in the floor and pushed Jack out into his war. Floating toward the ground, he had never felt “a greater sense of jubilation.” The experience was so exhilarating he shouted “God damn,” and earned an instant reprimand from Russell.

In the coming weeks, Jack proved to be his father’s son but also his own man. In addition to fishing behind the Germans’ backs, he swiftly developed good combat skills. He was brave, practical, and level-headed. Like his comrade and role model Russell, he seemed to actually enjoy fighting. Unlike his father, who was not always a good team player, the younger Hemingway worked well with others, whatever their rank or nationality.

After landing in Hérault, Russell and Hemingway quickly faced and dealt with challenges that read like problems for junior officers in training. The team’s radios did not survive the landing, leaving the men out of touch with their parent command. By the time Operation Dragoon got underway on August 15, they had yet to collect any useful information about the region. This eliminated the need for their most important mission—scouting for the invasion route. They were now on their own to find ways to accomplish their second mission: work with the Resistance to fight the Germans.

THE TWO YOUNG OFFICERS considered their options and decided to arm any resisters ready to fight and—not unlike Robert Jordan in For Whom The Bell Tolls—proceeded to direct small-scale guerrilla operations, including an ambush in which Hemingway drew his first blood. Firing his Thompson, he mortally wounded a young German soldier (and then arranged for his care until he died the next day). Wise enough to steer clear of the large German formations withdrawing to the northeast, Hemingway and Russell were probably the first uniformed Allied soldiers to enter the small city of Montpellier from the southwest after the Germans had left. On the morning in late August when tanks from the French II Corps rolled in, its soldiers standing in the turrets and waving to the crowds as if they had gotten there first, Hemingway and Russell were sitting in a café on the town square, nursing hangovers and watching the spectacle.

By early September, the pair had reported to the Strategic Services Section of the Seventh Army, the senior U.S. command in the area. They became part of a larger cohort responsible for a variety of ad hoc OSS missions. One of those missions was to recruit, train, and infiltrate line-crossers—innocent-looking locals who could report on what they saw on the German side of the front while they went about their daily business.

There was art and science to studying the terrain, reaching out to friendly units, and finding just the right time and place to slip an agent across. Hemingway was a quick study, learning on the job as summer turned to fall. But, on October 28, 1944, one such mission near a place called Hérival in the Vosges Mountains went very wrong when Hemingway, along with two others, stumbled on German mountain troops digging foxholes in a patch of dense forest. Three rounds to his right arm and shoulder brought him down before he could bring his submachine gun to bear. To keep from being shot again, he shouted, “Kamerad!”: “Comrade!” in German, meaning “I give up” to every infantryman on both sides. He was now a prisoner of war.

Perhaps because he was still wearing his MP branch insignia and did not appear to be part of the OSS, or perhaps because he was named Hemingway, Jack was at first “very well treated and cared for,” in the words of an official report he wrote after his liberation in 1945: “The Germans were lacking in medical supplies but did everything they could for us.” Years later, he would add that when he first gave his name, rank, and serial number, his captor asked if he had ever been at a ski resort in Schruns, Austria. The answer was yes. When asked the name of his nursemaid, Jack answered that it had been the beautiful “Tiddy,” whereupon the German broke into a grin, saying she was his girlfriend and producing a bottle of schnapps to drink a toast to better times.

Jack eventually wound up in Oflag XIII-B, a camp for officers near Hammelburg in the heart of western Germany. There, he settled into the misery of late-war camp life: a 900-calorie daily diet of bread and rutabaga soup; shabby, overcrowded barracks; and the threat of accidental Allied air attack. Perhaps the greatest danger to the prisoners came when Third Army commander Lieutenant General George S. Patton launched an ill-advised and costly raid in late March 1945 to rescue his son-in-law, also being held in XIII-B.

The raiders—a 300-man task force of tanks and infantry from the 4th Armored Division—punched through German lines and traveled across some 40 miles of enemy territory to reach the camp late on the afternoon of March 27, 1945, crashing through the fence and routing a handful of overage defenders. Jack and his fellow prisoners now had three choices: stay put and wait for liberation, hitch a ride with the task force, or strike out on their own for U.S. lines. Like Frederic Henry in A Farewell to Arms, the young Hemingway and another officer opted for the last.

For the next few days, they lived rough while moving west, trying to avoid other prisoners (who might attract unwanted attention) and German patrols. Sleeping in the open, they were, in the words of Jack’s 1986 memoir, “famished, thirsty, cold, and stiff” most of the time—digging up root cellars and even killing an enemy’s pet rabbit to survive.

A patrol of nervous, underage German soldiers eventually surprised them. One pointed a Schmeisser machine pistol at Jack’s stomach, his finger trembling on the trigger, and could have ended young Hemingway’s life with a twitch. Jack stood as still as he could, keeping his hands in the air. Speaking softly, he asked in broken German to speak to a noncommissioned officer—that is, an adult who could take charge and get the Americans safely behind wire with other prisoners of war. This is exactly what happened after a German sergeant appeared and took charge of the prisoners, who were shunted to two massive camps holding thousands of captured officers. The first was near Nuremberg and the second, Stalag VII-A, at Moosburg, on the Isar River in Bavaria. Jack spent the remaining weeks of the war at the latter, returning to Allied control on April 29, 1945, when the U.S. 14th Armored Division liberated the camp. By then his weight had dropped from around 200 to under 150 pounds.

JACK HEMINGWAY WOULD eventually receive both the Bronze Star and the French Croix de Guerre. A May 1945 award recommendation in Jack’s file notes the “minor acts of heroism” Lieutenant Hemingway performed several times. His record in captivity also came in for praise. “This officer has weathered experiences in combat…been wounded and [taken] prisoner…all without untoward emotional reactions,” an OSS evaluation of his fitness for duty in July 1945 found. “He is quite mature despite his youth. His motivation for service in the field is of the highest. His social relations are good; he is frank and engaging in manner. He is not particularly reflective and…will work most effectively under direction, but he is resourceful, courageous and sufficiently self-assured to be an excellent operations officer.”

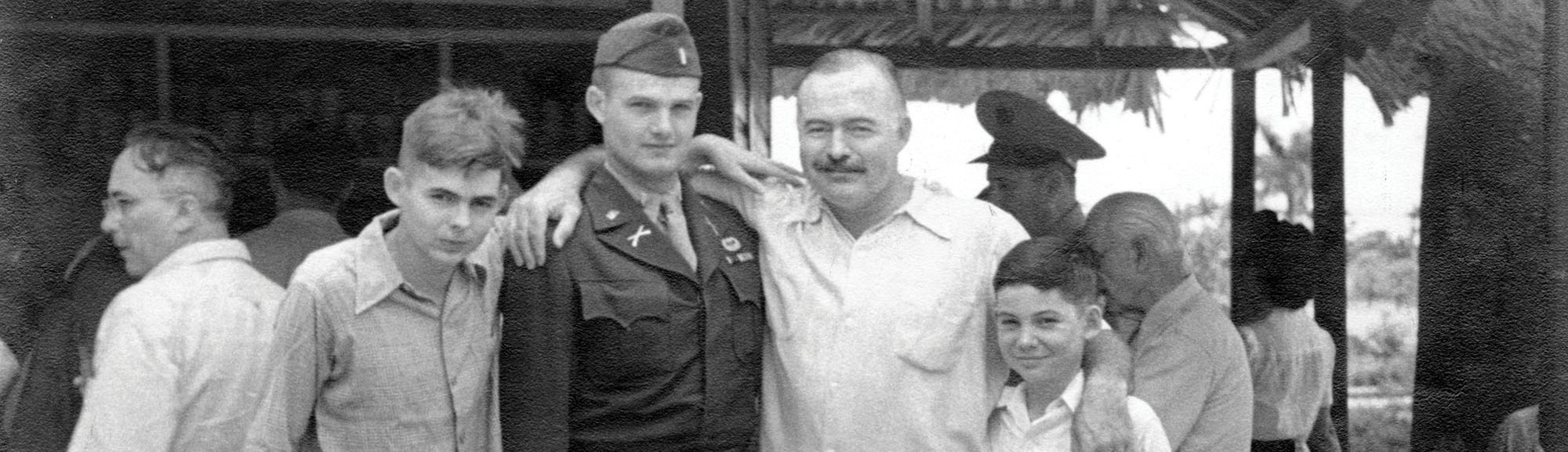

When he and his father were reunited late in the spring of 1945, Ernest, too, was impressed by the ways that Jack had grown up during the war. After spending time with Jack and his two half brothers in Cuba, the senior Hemingway wrote approvingly of his son’s exploits: how Jack had had “some good fights” organizing resistance behind German enemy lines; how he had refused to allow the German doctors to amputate his wounded arm; how he was ready and willing to deploy again, this time to the Pacific, where the war against the Japanese was still raging.

As Jack’s luck would have it, that war would end before he could redeploy and, through the fall of 1945, he stayed on the East Coast, serving first in Washington, DC, at OSS headquarters, and then in Virginia, helping to guard German prisoners of war.

Jack Hemingway’s OSS experience marked him for years. After the war, he found himself again in uniform, serving in U.S. Army intelligence assignments in Germany, a natural follow-on to his wartime service. When he married, at Hadley’s Paris apartment in 1949, the guests would include two former OSS members destined for greatness. One was Ernest’s friend, David K. E. Bruce, the former commander of the OSS in Europe, already an ambassador. Standing up for Jack’s bride was Hadley’s friend, the future chef Julia Child. She had served with the OSS in Washington and Asia and happened to be living in the French capital, where she was absorbing the lessons of French cuisine, and was tall enough to serve as matron of honor for the tall and lovely bride, Byra Whittlesey.

With Byra, Jack would raise three daughters, two of them, Mariel and Margaux, destined for Hollywood. Jack himself would comment with bittersweet pride that he was not himself famous but had a famous father and famous daughters. He could also have said, despite the lack of fame, that he had more than measured up to the Hemingway code in World War II. ✯

IN THE SHADOW OF FAME

Ernest Hemingway’s younger brother, Leicester, tried but mostly failed to follow in Ernest’s and Jack’s footsteps. Born in 1915, Leicester applied in 1941 to join the office of the Coordinator of Information, a forerunner of the OSS. He was discouraged—perhaps sabotaged—by Ernest, who told Leicester, then 26, that he was too old for active service, besides having a wife and children. (Ernest did not believe that his own age—42 in the summer of 1941—and a wife and three children disqualified him from adventures on the battlefield.) Leicester instead spent much of the war in Washington, DC, with the Federal Communications Commission before enlisting in the Army Signal Corps as a filmmaker. When Jack fell into German hands in 1944, Leicester volunteered to replace his nephew in the OSS, but, not unlike Ernest, was turned down as unqualified. (In 1943, OSS headquarters had turned down a recommendation to enlist Ernest, believing him too independent to submit to military discipline.) Leicester nevertheless made his way to the front, serving in France with the 4th Infantry Division—the unit to which Ernest was accredited as a war correspondent. Ernest had to admit, somewhat grudgingly, that the brother he had “always considered a violently useless character” might have “some decent blood” after all. A few years later, Leicester wrote a book closely based on his wartime experiences; The Sound of the Trumpet was not well received when it appeared in 1953, the year before Ernest won the Nobel Prize for Literature. After an imaginative but disastrous attempt to create an independent country, “New Atlantis,” on a coral reef off Jamaica, and years of suffering from diabetes, Leicester committed suicide in 1982 at the age of 67, joining a sad procession of Hemingways who died at their own hands—principal among them his father Clarence and brother Ernest. —Nicholas Reynolds