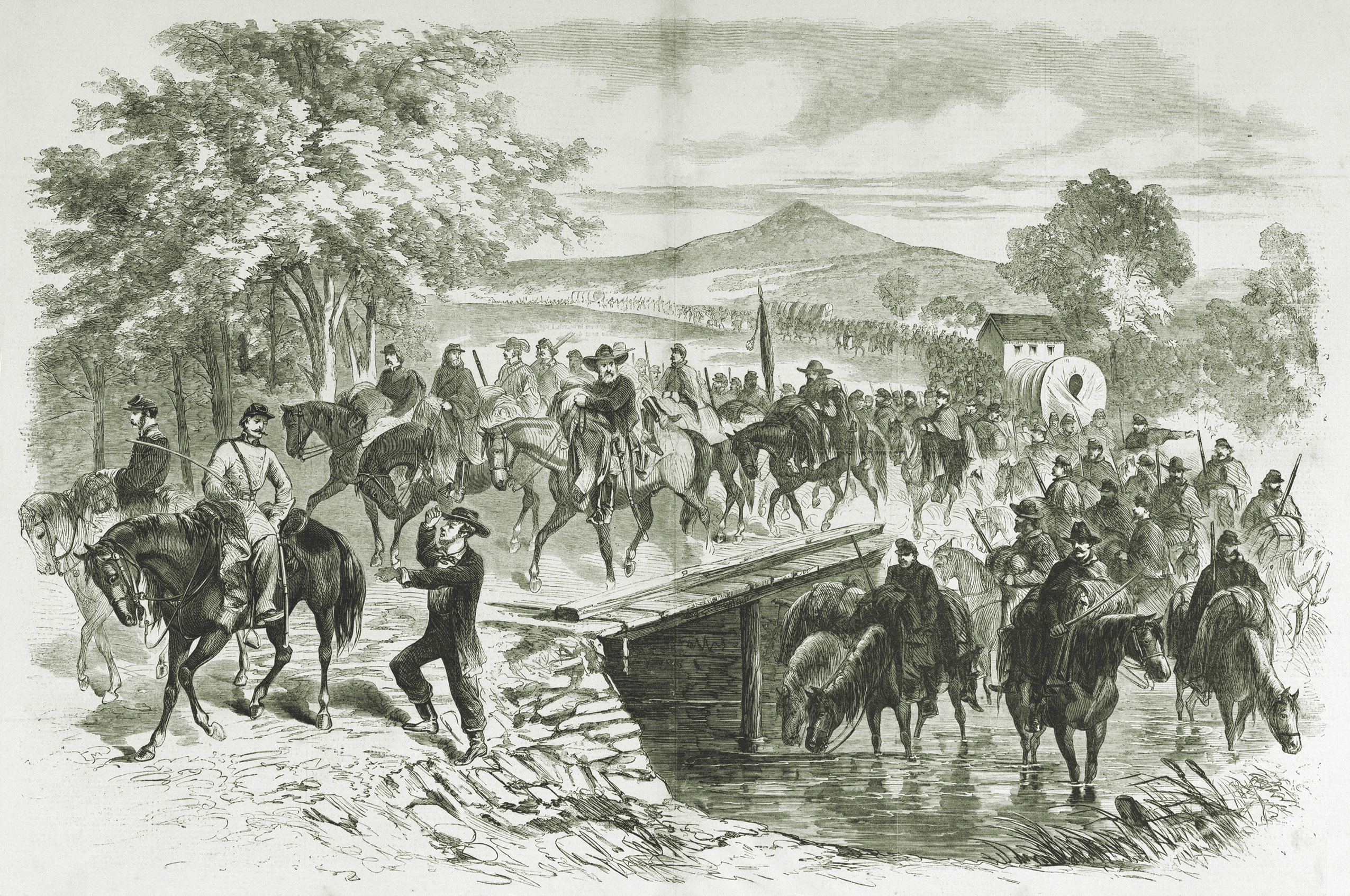

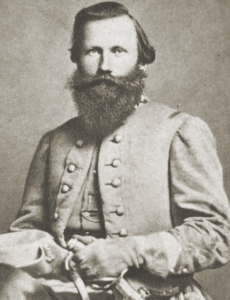

J.E.B. Stuart’s second “Ride Around McClellan” proved just as critical as his more famous first

The 1862 Maryland Campaign had left the Army of Northern Virginia badly damaged. Now with thousands of stragglers, wounded, and sick scattered across the lower end of the Shenandoah Valley, General Robert E. Lee needed time to restructure his army. He had to absorb newly arriving conscripts and recovered sick and wounded from the Peninsula Campaign; collect his stragglers; evacuate his sick and wounded; and gather supplies. It was a tall order, and to achieve it Lee needed the Union Army of the Potomac to leave him alone. A conventional commander would have withdrawn closer to his army’s rail communications at Staunton, Va., some 90 miles to the south, but that would have entailed abandoning many of his stragglers, sick, and wounded to the enemy, which Lee refused to do. Instead, he chose to reorganize the army near Winchester, which placed him close to the Union forces in Maryland. It was a bold and risky decision because of the condition of his army, but Lee knew he faced a cautious commander in Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. Because an aggressive posture might keep McClellan thinking defensively, Lee had his cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, push his pickets up to the Potomac to suggest strength and prevent enemy patrols and scouts from getting close to the main body of the army to ascertain its true condition.

during his 130-mile excursion. (DL Archive/Alamy Stock Photo)

Lee’s strategy worked. McClellan overestimated the Confederates’ strength and condition and focused on guarding the line of the Potomac rather than pressing and probing the enemy. But to keep McClellan further off-balance, Lee felt a cavalry raid into the Federal rear would help him learn what McClellan was up to. Was he preparing a new campaign into the Shenandoah or had he detached part of his army to threaten the Confederates on a different front? Union cavalry, however, were watching all fordable points on the Potomac, so on October 4, Lee arranged for a force under Colonel John D. Imboden to mount a raid in the direction of Cumberland, Md. As Lee had hoped, the raid drew away some of the Union’s mounted arm. In sending one of his precious cavalry brigades in pursuit of Imboden, McClellan cleared the way for Lee to strike. On October 8, he ordered Stuart to assemble a detachment of 1,200–1,500 troopers, cross the Potomac above Williamsport, ride to Chambersburg, destroy the bridge over the Conococheague Creek, and inflict any other damage on military equipment and installations in the area. He was also asked to “gain all the information of the position, force, and probable intention of the enemy which you can.” Apart from that, Lee gave Stuart great discretion in how to conduct the operation, writing, “reliance is placed upon your skill and judgment in the successful execution of this plan, and it is not intended or desired you should jeopardize the safety of your command, or go farther than your good judgment and prudence may dictate.” In other words: no unnecessary risks.

With a force of 1,800 troopers and four pieces of field artillery, Stuart on the 9th marched from Darkesville, Va., to Hedgesville, two miles below the Potomac, and camped for the night out of sight of enemy scouts. At daylight on the 10th the Southern horsemen crossed the river at McCoy’s Ferry and moved rapidly, narrowly missing an encounter with the Union division of Maj. Gen. Jacob D. Cox, who had been ordered to the Kanawha Valley. By noon, they had covered nearly 26 miles, reaching Mercersburg, Pa. Intending to march next on Hagerstown—a large Union supply hub—Stuart learned that enemy forces there were on the alert and adjusted, heading instead to Chambersburg. He arrived, unexpected, at dark, to complete a ride of more than 50 miles.

All vestiges of Union authority had departed and the graycoats took control of the city without incident. The troopers proceeded to cut telegraph wires, paroled sick and wounded Union soldiers in hospitals in the city, seized nearly 300 horses from residents, destroyed railroad facilities, as well as a large quantity of equipment, clothing, weapons, and ammunition.

“After mature consideration,” Stuart decided to head next for Leesburg, Va. Knowing it was necessary to deceive the enemy as to his true destination, however, he marched toward Gettysburg. But after crossing South Mountain, he turned south, feinting toward Hagerstown before changing direction again, marching back through South Mountain and emerging at Emmitsburg, Md., 12 miles south of Gettysburg. He pressed on toward Frederick, eluding Union detachments frantically trying to track him down, but again deviated from the course the enemy presumed he would take and cut southeast through Liberty and New Market. By daylight, he reached Hyattstown, having covered 70 miles.

Learning 4,000–5,000 Union soldiers had collected around Poolesville, near where he wanted to cross the Potomac, and that all nearby fords were guarded, Stuart again relied on deception to keep the enemy guessing. On the morning of the 12th, he proceeded directly on Poolesville to give the impression that was his target before cutting west to where the Monocacy River emptied into the Potomac. Employing skillful combined arms tactics with mounted and dismounted troopers, and his artillery, he dispersed the defenders in his path and crossed at White’s Ford, the same point much of Lee’s army had used to enter Maryland back in September.

Stuart had escaped to Virginia having lost in two days only a handful with minor wounds. As he had famously done near Richmond in the spring, he had ridden around the entire Army of the Potomac, covering nearly 130 miles and confirming for Lee that the entire Federal army remained in place. “The results of this expedition, in a moral and political point of view, can hardly be estimated,” Stuart claimed. That wasn’t bombast either. In those areas, it had succeeded beyond Lee’s and Stuart’s most ambitious hopes. The seemingly fumbling, hapless Union effort to trap Stuart, caused McClellan great embarrassment and inflicted damage on his already fragile relationship with the Lincoln administration from which it never recovered. It also eroded the Union army’s confidence in its cavalry.

“I fear our cavalry is an awful botch,” Colonel Charles Wainwright of the 1st Corps complained unfairly, when it was McClellan’s defensive posture that had kept his cavalry erratically dispersed. What had actually made the Federals look foolish was Stuart’s superb management of the raid. He had seized the initiative, moved faster than anticipated, never took the route they expected, was informed by excellent intelligence about enemy movements, and acted boldly but prudently.

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.