Duing the late 1930s, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was fond of putting on impressive shows to demonstrate his country’s martial capabilities. For displaying Italian air power, his weapon of choice was a large attack bomber whose hefty fuselage was lent a look of blunt-nosed pugnacity by its single radial engine. To foreign observers prior to World War II, the Breda Ba.65 was the dominant symbol of Italian air power.

After Italy entered the conflict, the Ba.65 would continue to serve as a symbol—of Italian aerial impotence.

The Ba.65 sprang from one of those tantalizing concepts for which aircraft designers frequently strive, but seldom achieve—a flying military jack-of-all-trades. In Italy, such a requirement was formulated by Colonello Amadeo Mecozzi as he set about procuring a modern ground-attack plane for the Regia Aeronautica. For Meccozi, the ideal military airplane was one that would be able to perform a wide variety of functions—fighter, light bomber, army cooperation and photoreconnaissance.

Of several designs submitted to satisfy that ambitious specification, that of the Societa Italiana Ernesto Breda was ultimately selected. Developed in 1932 from the Breda 27 single-seat fighter, the Breda 64 was completed early in 1933 as a cantilever monoplane. It was constructed using a frame of chrome-molybdenum tubing skinned with metal, except for fabric over the rear fuselage and control surfaces. The Ba.64 prototype was powered by a Bristol Pegasus radial engine, license-built by Alfa Romeo, in a long-chord cowling, which was later replaced by an Alfa Romeo 125 RC35 engine rated at 650 hp. In contrast to the Breda 27’s fixed landing gear, the Ba.64’s undercarriage retracted rearward into the wings. The headrest behind the open cockpit was extended as a streamlined fairing all the way down the fuselage upper decking to the tail. Armament consisted of four 7.7mm Breda-SAFAT guns in the wings and up to 880 pounds of bombs in racks under the wings.

The fundamental problem with the Ba.64 was its size in relation to its power plant—a wingspan of 39 feet, a length of 31 feet 6 inches, a height of 10 feet 5 inches, an empty weight of 3,291 pounds and a loaded weight of 5,489 pounds. With a maximum speed of 220 mph, the new aircraft lacked the performance to be a very effective attack or reconnaissance plane, let alone a successful fighter.

The first production Ba.64s reached Rome’s Ciampino airfield in the summer of 1936 and were regarded as a profound disappointment by their pilots. The Ba.64’s mediocre speed and heavy handling characteristics were anything but fighterlike, and its tendency to go into a high-speed stall—an unnerving surprise to pilots accustomed to more forgiving biplanes—caused several fatal crashes. In 1937, the Ba.64s took part in a series of well-publicized military maneuvers, but they were withdrawn from service the following year.

Modified into two-seaters with a 7.7mm machine gun in the rear, only a small number of Ba.64s were built for the Regia Aeronautica, since Breda was already working on an improved model, the Ba.65. Two Ba.64s were purchased by the Soviet Union in 1938. One was delivered to General Francisco Franco’s Nationalist forces in June 1937 and saw brief service during the Spanish Civil War.

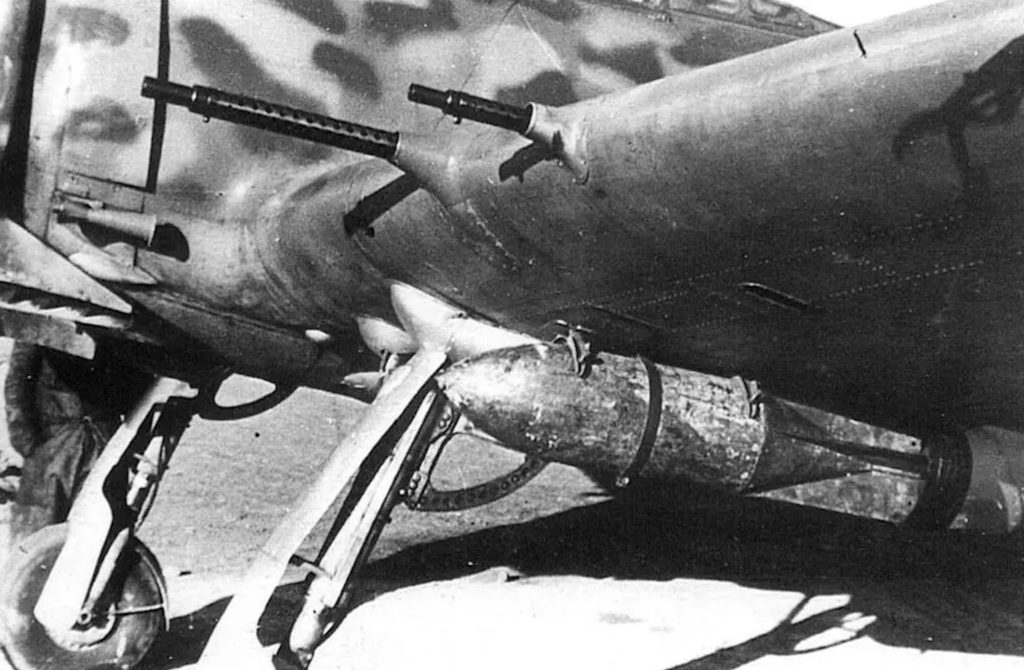

Evolved from the Ba.64, the Ba.65 was also a single-seat, all-metal, cantilever low-wing monoplane with aft-retracting main undercarriage. Initially intended as an interceptor and attack-reconnaissance plane—although the pretense that it was a fighter soon disappeared—the Ba.65 carried wing-mounted armament of two 12.7mm and two 7.7mm Breda-SAFAT machine guns, and provided internal stowage for a 440-pound bombload in addition to external ordnance that—in theory, at least–could total 2,200 pounds. The prototype, which was first test-flown by Ambrogio Colombo in September 1935, was powered by a Fiat A80 RC41 18-cylinder, twin-row radial engine with a takeoff rating of 1,000 hp.

Production of the Ba.65 began in 1936, the initial model having an Isotta-Fraschini-built Gnôme-Rhône 14K 14-cylinder radial of 900 hp. The single-seat Gnôme-Rhône version of the Ba.65, of which 81 were built, attained a maximum speed of 258 mph at 16,400 feet and 217 mph at sea level. Maximum cruising speed was 223 mph at 13,125 feet, and range was 466 miles with a 440-pound bombload. The plane could reach an altitude of 13,125 feet in eight minutes, 40 seconds, and its service ceiling was 25,590 feet. Empty and loaded weights were 5,291 pounds and 6,504 pounds, respectively. Wingspan was 39 feet 1/2 inches, wing area was 252.95 square feet, length was 31 feet 6 inches, and height was 10 feet 11 inches.

In December 1936, Mussolini, stepping beyond his effort to instill a more martial spirit in his people with propaganda flyovers of Ba.64s, decided to give his military personnel some experience in a real conflict—the Spanish Civil War. His program to assist Franco’s Nationalists included the establishment of a 250-plane aerial contingent, the Aviazione Legionaria. The first installment of that force consisted of four Ba.65s unloaded at Palma, Mallorca, on December 28, to be joined by eight more on January 8, 1937. In March, the attack planes were transported to Cádiz, along with newly arrived Fiat C.R.32 fighters, on the steamship Aerienne. The last of the Ba.65s arrived on May 3 and were formed into the 65a Squadriglia Autonoma di Assalto under the command of Capitano Vittorio Desiderio. Teething troubles were soon experienced with the new planes, and aircraft No. 16-29 was wrecked in a landing accident. Not until August did the unit begin operations, but on August 24 one of its pilots, a Sergente Dell’Aqua, scored a unique air-to-air victory when he encountered a lone twin-engine Tupolev SB-2 Katiuska bomber over Soria and shot it down.

During operations in northern Spain, several Ba.65s were converted to two-seaters, and one was experimentally fitted with an A360 two-way radio. At the end of the campaign in October, the squadron, now commanded by Capitano Duilio S. Fanali, was transferred to Tudela in Navarra, and in December the Bredas braved bitter winter weather conditions to participate in the battles for Teruel. After that city fell, the 65a Squadriglia, bolstered by the arrival of four more Ba.65s, took part in the Aragon offensive, which by April 15 had succeeded in cutting the Spanish Republic in two. During the Nationalist advance, the Ba.65s harassed retreating Republican troops, attacked artillery batteries and landing grounds, and bombed railway and road junctions.

During the Battle of the Ebro in July 1938, the 65a Squadriglia, now under the command of Capitano Antonio Miotto, used its Ba.65s as dive bombers for the first time, striking at pontoon bridges that the Republicans had thrown across the Ebro River. By September 1938, attrition had whittled the squadron’s complement of aircraft down to eight, but six more Ba.65s arrived, and in January 1939 the squadron—again under a new commander, Capitano Giorgio Grossi—was at Logroño and ready to take part in the final offensive against Catalonia.

The Ba.65s’ final mission was flown from Olmedo on March 24. When the war ended five days later, the 65a Squadriglia had logged 1,921 sorties, including 368 ground-strafing and 59 dive-bombing attacks. Of the 23 Ba.65s sent to Spain, 12 had been lost—an acceptable enough record if one discounted the relative ineffectiveness of the aerial opposition they faced most of the time. When the airmen of the Aviazione Legionaria returned to Italy in May, they bequeathed their 11 surviving Ba.65s to the Spanish Ejercito del Aire.

While the Ba.65 was being blooded over Spain, a two-seat version, the Ba-65bis, had been developed, and export orders for the Breda assault monoplane had been solicited. Fifteen aircraft with 14K engines were ordered in 1937 by the Royal Iraqi Air Force (RIAF), 13 of which were Ba.65bis two-seaters equipped with a hydraulically operated Breda L dorsal turret mounting a 12.7mm Breda-SAFAT machine gun; the remaining two were dual-control trainers. Ten single-seat Ba.65s were delivered to the Soviet Union, and in 1938, 20 Ba.65s equipped with Piaggio P.XI C.40 engines—17 single-seat attack planes and three dual-control trainers—were delivered to Chile. In 1939, 12 Ba.65bis models with Fiat A80 engines and power turrets were ordered by Portugal for its Arma da Aeronautica. In June 1937, a Ba.65 was experimentally fitted with an American Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engine in anticipation of an export order from Nationalist China that was never placed.

When Italy entered World War II in June 1940, the Regia Aeronautica had 154 Breda Ba.65s in its inventory, including 119 fitted with Fiat A80 RC41 engines and a small number of Ba.65bis two-seaters with a manually operated 12.7mm machine gun in the rear gunner’s pit rather than the Breda L turret. Owing to the unsatisfactory performance of the Fiat A80 RC41 under desert conditions, all Ba.65s with that power plant were re-engined with the Isotta-Fraschini-built Gnôme-Rhône 14K before being committed to North Africa.

In September 1939, Ba.65s equipped the 101a and 102a Squadriglie of the 19o Gruppo of the 5o Stormo, the 159a and 160a Squadriglie of the 12o Gruppo, and 167a and 168a Squadriglie of the 16o Gruppo, both components of the 50o Stormo. Soon after Italy entered the war on June 10, 1940, however, it became clear that the large single-engine attack bomber was as ungainly and vulnerable to enemy fighters as was its British contemporary, the Fairey Battle. During the Italian invasions of France and Greece, Ba.65s were conspicuous by their absence.

By mid-1940, the only Ba.65s in a position to see any combat were those of the 50o Stormo in North Africa, and even they ended up contributing little to Italian operations there. The principal units involved were the 159a Squadriglia under Capitano Antonio Dell’Oro, and the 160a Squadriglia under Capitano Duilio Fanali. Usually their missions involved flying about 150 miles to attack British tanks, armored cars and other vehicles from altitudes of about 1,000 feet. Due to a shortage of high-explosive bombs, however, the Bredas usually carried incendiary bombs that caused relatively little destruction on rocky ground or in sand, which tended to contain the fires they caused. Steady attrition, a shortage of spare parts and a realization by the Italian army that the Ba.65s were not really an effective weapon resulted in the replacement of the Bredas in the 160a Squadriglia with the Fiat C.R.32 Quater, a close-support fighter-bomber adaptation of the 1932-vintage C.R.32 biplane fighter.

The embarassing superiority of the C.R.32 over its supposedly more modern monoplane contemporary was underlined on August 4, 1940. At 5 p.m. that day, six Ba.65s of the 159a Squadriglia, led by Capitano Dell’Oro, attacked British vehicles at Bir Taib el Esem, while six Fiat C.R.32s of the 160a Squadriglia, led by Fanali, waited 3,000 feet above to follow up their strike. The Bredas were about to make their third and last strafing run when they encountered a Westland Lysander of No. 208 Squadron, escorted by four Gloster Gladiator biplane fighters of No. 80 Squadron, flown by Flight Lt. Marmaduke T. St.J. Pattle, Flying Officers Peter G. Wykeham-Barnes and John Lancaster and Sergeant Rew. The Gladiators promptly attacked the Bredas, Pattle and Wykeham-Barnes downing two of them. At that point, however, the C.R.32s dove on the British fighters, claiming three of the Gladiators. The fourth Gladiator, flown by Lancaster, was damaged but returned to its base. Pattle actually escaped the C.R.32s only to encounter three more Bredas and 12 Fiat C.R.42s, the latter of which shot him down after a 15-minute fight.

Although Pattle was credited with a C.R.32 as well as one of the Ba.65s, all of the Fiats in fact returned to their airfield, where Capitano Fanali was credited with one of the Gladiators, and a Maresciallo Cantelli was credited with two. Sergeant Rew was killed, but Pattle and Wykeham-Barnes managed to bail out of their stricken planes and, after being found in the desert by armored cars of the 11th Hussars, returned to British lines. Both pilots would later become aces, Pattle accumulating an unofficial score of 52 to become the top-scoring fighter pilot in the Royal Air Force before being killed in action over Greece on April 20, 1941. Wykeham-Barnes survived the war with 17 victories.

In September, the 168a Squadriglia, equipped with 14K-powered Bredas, commenced operations alongside the beleaguered 159a. On October 8, 1940, Capitano Dell’Oro was shot down and killed during an air attack near the wells of Bir Kamsat. He was posthumously awarded the Medaglia d’Oro al Valor Militaire, and all aircraft in the 159a Squadriglia carried his name under their cockpits thereafter. In December 1940 the British went over to the offensive, and the Ba.65s, joined by a few reinforcements from Italy, fought valiantly but vainly to stem the onslaught. At the end of December, the 168a Squadriglia, its aircraft decimated by foul weather conditions as well as combat losses, was disbanded. At the end of January 1941, the advancing British found six dilapidated Ba.65s lying abandoned at Benghazi airfield. The surviving aircrews of the 159a Squadriglia were transferred either to fighter squadrons or to dive-bombing units equipped with a German import, the Junkers Ju-87B Stuka.

The Ba.65’s ill-starred combat career was briefly revived on May 2, 1941, when hostilities broke out between British forces in Iraq and that country’s anti-British, pro-German chief of the National Defense Government, Rashid Ali el Ghailani. Among the Iraqi aircraft that attacked the RAF base at Habbaniya that day were some of the 13 Ba.65bis machines that had been delivered to Iraq in 1938 and assigned to No. 5 Squadron, RIAF. Although three British aircraft were destroyed on the ground in the initial strike, subsequent Iraqi sorties were disrupted by Habbaniya’s defenders. Later that same day, Flying Officer J.M. Craigie, flying a Gladiator of Habbaniya’s ad hoc fighter flight, was about to land when he saw a Ba.65 coming in to bomb the field. Pulling up, he fired at the Breda and forced it to break off its attack, although he failed to bring it down.

Over the next few weeks, damage from aerial opposition and groundfire, combined with inadequate maintenance facilities and an insufficient supply of spare parts, eventually grounded all the Iraqi aircraft. Despite some desultory aid from the Germans and Italians, the Iraqis failed to drive out the British, who were soon invading Iraq. On May 30, Rashid Ali fled the country. An armistice was signed the next day, ending the Iraqi revolt and the fighting career of the Breda Ba.65.

Over the next two years, the Regia Aeronautica assigned the Ba.65’s ground-attack tasks to other aircraft—medium bombers like the Savoia-Marchetti S.M.79, converted fighters like the Macchi M.C.200, or imports like the Junkers Ju-87B Stuka. Even back in the mid-1930s, the Breda attack planes failed to live up to the promise suggested by their advanced appearance. During World War II, while some aircraft designs like the Supermarine Spitfire and the Messerschmitt Me-109 were good enough for improved versions to fight throughout the conflict, the Breda Ba.65 did not survive its first year. Ill-conceived from its very inception, the plane’s brief combat career ensured it a dubious place in history as arguably the worst attack plane of World War II.