Frantically trying to determine the origin of a roaring sound, the caretaker grabbed an ax, climbed atop Ashwood Hall, and slashed through the tin, resin, and gravel roof of the mansion in rural Ashwood, Tenn. Then “a terrible flame leapt out like a wild beast released from prison.”

Whoosh!

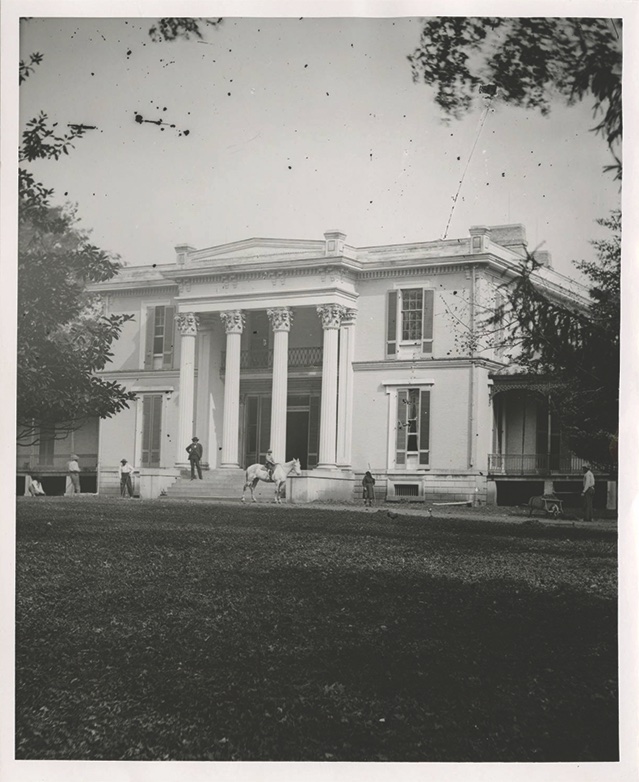

Ashwood Hall—once one of the “handsomest country residences in Tennessee”—was ablaze on the fall day in 1874, and no one could save it. Fortunately, Rebecca Polk—owner of the estate and widow of a former Confederate officer—was in Europe with her daughters; and except for a young man’s “fine shotgun,” most valuables in the uninsured mansion somehow were rescued from the flames. The ruins reportedly smoldered for two weeks.

Ashwood Hall was never rebuilt, but stories linger there (and treasure remains), for this was where an Episcopal bishop who became a Confederate general laid the foundation for a great estate in 1834; where hundreds of slaves toiled and worshipped; and where a teen became a Confederate heroine “in one of the loveliest spots in America.”

“Bring your boots,” farmer Campbell Ridley encourages me the rainy night before our visit to the Ashwood Hall site. The 78-year-old widower knows the rural area 40 miles south of Nashville better than most—“about seven generations” of his family have lived on his farm; and for two decades, the quipster/storyteller/U.S. Army vet has farmed land where Ashwood Hall once stood. Ridley’s farm shop is a musket shot from the Clifton Place mansion of Confederate Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow, his ancestor. Campbell’s grandfather, who relished eating hog brains, once owned the Pillow place, too.

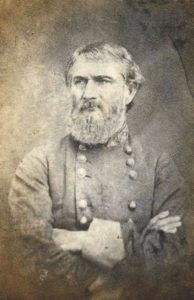

Joined by Maury County Archives Director Tom Price and my friend Jack Richards, we trudge through a field of corncobs and broken stalks to the Ashwood Hall site—about five miles from downtown Columbia, the county seat. Behind us, spring peepers make a god-awful racket in a marsh along Old Zion Road. From the rise about 200 yards from Mount Pleasant Pike—a wartime route used by both armies—we see in the distance the slave-constructed St. John’s Episcopal Church, the plantation chapel completed in 1842 under the direction of Leonidas Polk and his three brothers, George, Lucius, and Rufus.

Leonidas, who commanded the First Corps of the Army of Tennessee, became famous as the “Fighting Bishop”—the North Carolina-born soldier held various roles in the Episcopal Church during his lifetime, including Bishop of Louisiana. On June 14, 1864, the general was nearly sliced in two by a well-aimed Federal artillery round at Pine Mountain, Ga.

(My favorite Polk anecdote is about when at a christening for a slave’s child in Ashwood, he asked the young mother: “Name this child.” “Lucy, sir,” she replied. “That’s no fit name for a child!” bellowed the bishop, who thought the slave said “Lucifer.” Polk baptized the girl “John.”)

In what before the Civil War was the wealthiest county in Tennessee, the Polk brothers owned enormous, adjacent plantations—George, Rattle and Snap; Lucius, Hamilton Place; Rufus, West Brook; and Leonidas, Ashwood Hall. (Only the Rattle and Snap and Hamilton Place mansions stand today.)

“God’s country,” Confederate soldiers called the beautiful area.

Of the four plantations, Ashwood Hall may have been the most impressive, “surrounded by one of the most fertile and magnificent farms of which the new world can boast,” a local newspaper wrote of it. Leonidas and his wife, Frances Ann, furnished the mansion with pricey pieces shipped from such far-flung places as Philadelphia and New York City.

After Leonidas sold Ashwood Hall to his younger brother, Andrew, in 1845, the two-story mansion was greatly expanded. It included one-story wings, full-length windows, Corinthian columns, iron railings, a picture gallery, library, and billiard room. Plop the place in Beverly Hills today and no one would blink.

Unfortunately, I did not bring boots for our muddy sojourn to the site of Polk’s palace. But I did bring my imagination. I can picture Ashwood Hall’s once-exquisite grounds—the well-manicured lawns, the greenhouses, the orchards filled with fruit trees, the iron gates swinging from massive stone pillars surmounted by inverted carved, stone acorns, the Polk family symbol.

Look over there: Is that the Polks’ English gardener? Are those the rare animals the family stocked on the grounds? Is that Andrew Polk, a captain in the First Tennessee Cavalry, instructing soldiers in his Maury County Braves on the plantation? Do you see Confederate cavalry commander Earl Van Dorn, that married rascal, hitting on another lady in Ashwood Hall’s entryway?

Listen up: Can you hear Union Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Yankees blowing on the organ pipes they swiped from St. John’s Church as they march down Mount Pleasant Pike on the way to Shiloh? Or the chatter from a ball at the Hall with Confederate officers? Or John Bell Hood, “Old Wooden Head” himself, who briefly used Ashwood Hall as headquarters before the Confederates’ disaster at Franklin?

The only tangible evidence we find of Ashwood Hall are scattered pieces of brick and stone, a decrepit building that may have been the mansion’s kitchen, a railroad spike-like rod perhaps used for construction, and two massive, Ginkgo trees imported eons ago by the Polks from Japan. Ridley chuckles when he sees me examine those gnarled monsters. These Ashwood Hall relics have survived for roughly 170 years, but the Gingkoes his wife Patty planted at their house were short-timers.

Although we find little, much remains from the plantation era. With Ridley’s permission to hunt the private property, local detectorists Terry Hann and Dan VunCannon have uncovered scores of artifacts—a water pump with an 1854 patent date, broken pieces of dishes, a bronze piano foot, a gorgeous, decorative female figurine, an ornate wind-up key for a clock, the top of a champagne or wine bottle inlaid with gold, and a metal tag inscribed with Andrew Polk’s name. They even have a bucket full of burnt relics.

My favorite find is VunCannon’s bronze tag with “Leonidas Polk” and “Raleigh, N.C.” inscribed on it in cursive writing. Hann speculates it was Polk’s property at West Point, where he roomed with fellow cadet Albert Sidney Johnston, who later became Army of Tennessee commander and was killed at Shiloh. Hann and VunCannon believe more treasure await discovery—perhaps even the communion set Leonidas used at St. John’s Church. Could it be deep underground, in what was once the mansion basement?

Of course, the Yankees figure prominently in Ashwood Hall’s story, too. Hann discovered a mangled Federal box plate on the grounds. But he hasn’t found Andrew Polk’s silver—if any of it is still out here.

Eager to keep the treasure out of Federal hands, Polk and a family slave hid the silver somewhere on the Ashwood Hall grounds. When marauding U.S. Army soldiers found out, they demanded the slave tell them where. When he refused, the child—“about four years old,” according to an account—was held over a well. The slave’s repeated refusal apparently almost led to tragedy.

“[H]orrible to relate,” according to a diary of one of Polk’s relations, “they dropped it & in the agony of the moment the unfortunate father gratified their cupidity! One of the number caught the child, it is true, after it had fallen out of the father’s sight in the well curb, but the effect on him was the same as tho they had killed it.”

During the war, Ashwood Hall was stripped of livestock, horses, fences, and crops. But Andrew Polk, who was seriously wounded early in the war, got a teeny measure of revenge against the Federals…thanks to his precocious daughter.

My drive on Mount Pleasant Pike from Columbia to Ashwood Hall, past the convenience stores and other schlock, will never be the same after learning what happened on this stretch on July 13, 1863. Chased by three Yankees on horseback, 15-year-old Antoinette Polk—who had been visiting cousins in Columbia—dashed on the toll road astride her thoroughbred, Shiloh. (Apparently, she didn’t pay the fare.) The skilled rider’s aim: Race to Ashwood Hall, where Confederates were in danger of capture if she didn’t raise the alarm.

The Yankees were in Columbia!

The cavalrymen dug their spurs into their horses’ sides, straining to catch up with Antoinette. But she reached the mansion ahead of the Federals, roused the Confederates, and was taken almost fainting from Shiloh, whose mouth was covered with blood and foam from the bit.

The soldiers at Ashwood Hall avoided capture; Antoinette’s mission was accomplished. For her bravery, Nathan Bedford Forrest gave the teen a flag captured from Colonel Abel Streight’s brigade in 1863. You can see it today in the Maury County Archives in Columbia.

After the war, Antoinette traveled to Europe, where the “beauty and belle” became a “great favorite of the Italians.” Her riding exploits remained renowned—“she is a beautiful rider, fearless,” according to an 1872 letter. In 1877, Antoinette married a French nobleman, becoming Baroness De Charette. When she met a group of soldiers from Tennessee on leave in France during World War I, the baroness said, “I am going to kiss every one of you.”

“She felt, no doubt,” a Columbia newspaper wrote after the baroness’ death in 1919, “that in ministering to these men she was but performing another chapter in that romantic career that began more than half a century ago when she outrode a squad of Federal troops from Columbia to Ashwood and prevented the capture of Confederate soldiers billeted in the palatial home of her father, Ashwood Hall…”

Ah, Ashwood Hall. What a sight. What stories.

Just imagine the rest. ✯

John Banks is the author of two Civil War books and his popular Civil War blog (john-banks.blogspot.com). He lives in Nashville, Tenn.