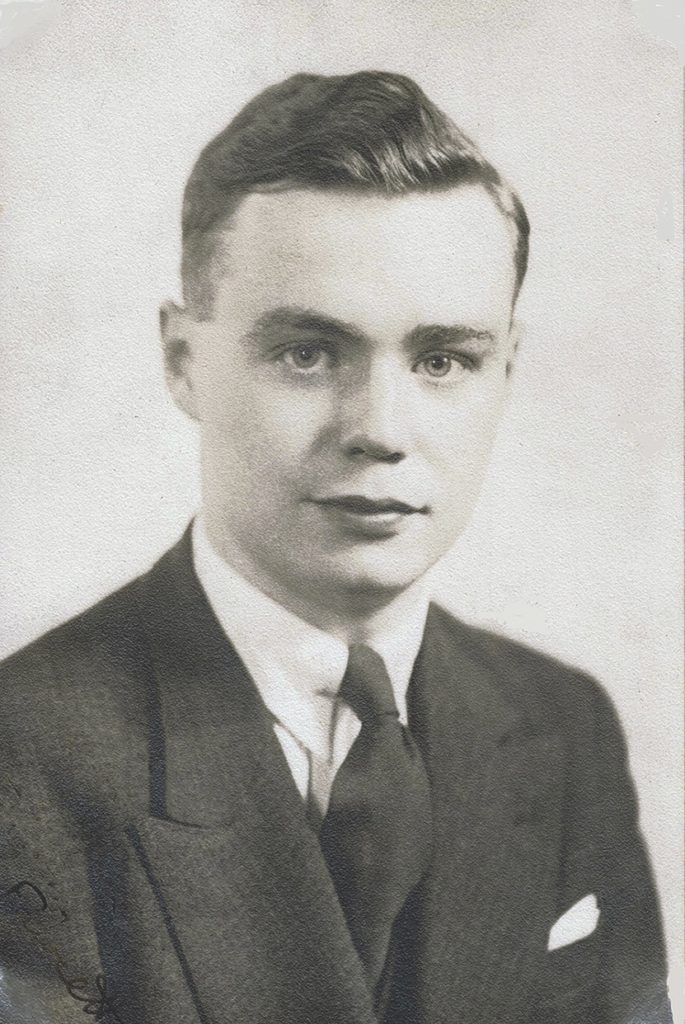

This Footlocker question comes from World War II’s associate editor, Kirstin Fawcett.

Q: My grandfather, Howard Fawcett, a chemical engineer working on contract with DuPont, was present at the University of Chicago in December 1942 when scientists initiated the world’s first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. He took analytical samples of the nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1, and somehow later obtained a tiny piece of graphite from it for posterity, leaving it in my uncle’s possession when he died in 1996. The graphite is preserved in a plastic cylinder and is slightly radioactive. Were mementos like this common and in accordance with safety protocols of the era?

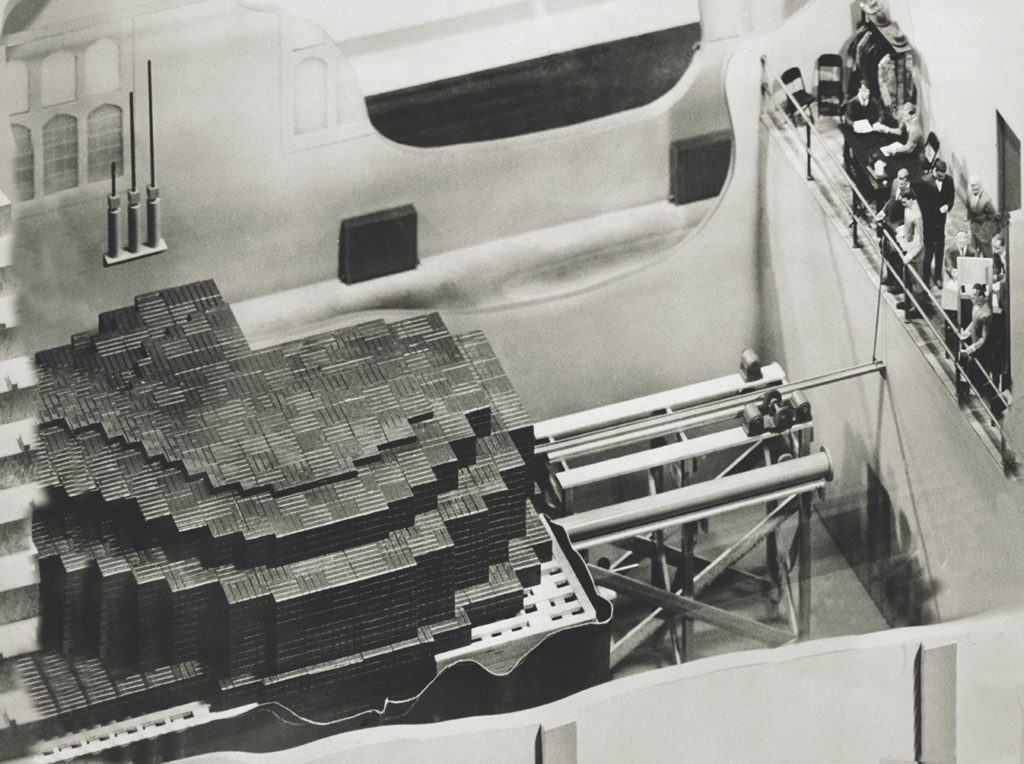

A: This is a fraction of the more than 770,000 pounds of dense graphite used to slow down high-velocity neutrons in one of the most important scientific experiments in human history. Though it would have world-changing implications, humanity’s first nuclear reactor was built on a dusty squash court below the crumbling stands of an abandoned football stadium at the University of Chicago.

It is fair to say that early experiments with nuclear power were shockingly reckless. Atomic Energy Commission historians later admitted that Enrico Fermi’s success producing the world’s first manmade nuclear chain reaction on December 2, 1942, was the result of “a gamble.” Tinkering with nature’s most powerful and as-yet not fully understood forces could have ended in an explosion or a runaway reaction near the heart of one of America’s biggest cities.

However, the categorical achievement of Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) opened the door to large-scale plutonium production, which meant that the creation of an atomic bomb was now more than just theoretical. Also, humans could use these same atomic building blocks to harness nuclear power. The world would never be the same again.

Later tests took place in more remote locations, and remnants of the original structure surrounding the historic splitting of nuclei on Chicago’s South Side became souvenirs. True to the incautious practices of the era, Lucite-encased strips and blocks of graphite from CP-1 were officially presented as keepsakes by the Argonne National Laboratory, the American Nuclear Society, and the University of Chicago, among others. The latter gave these little mementoes to donors, professors, and contributors to the project, like your grandfather.

Nuclear souvenirs are somewhat rare but not unheard of. Collectors pay large sums of money for a 1950s toy lab set with vials of real uranium, a commemorative coin intentionally exposed in an under- ground test, or a workman’s badge from the Chernobyl power plant. Perhaps the most famous and plentiful irradiated keepsakes are Trinitite—glassy pieces of nuclear-blasted sand from the July 16, 1945, Trinity test in the New Mexico desert.

Are these artifacts from the nuclear age radioactive? Most assuredly, yes. But whether they are dangerous is a slightly different question. I’ll preface my response by saying I am no Einstein, and I am no Oppenheimer either. These keepsakes commonly have low levels of initial exposure. This fact, combined with decades of decay time and some amount of protection offered by the Lucite blocks, goes a long way toward limiting their potency. That being said, I would resist the temptation to sleep with this nuclear souvenir under your pillow.

—Cory Graff, Curator