Filmmakers these days can’t seem to do Ireland justice. Despite being on the cutting edge of modern technology and communication, Irish people in recent years have experienced depictions of themselves reminiscent of tropes stretching back to the 19th century and beyond.

What are these stereotypes, and why are they still in films today?

‘The Rings Of Power’ Controversy

Irish stereotypes made headlines recently for the debut of Amazon’s new TV series “The Rings of Power.” This highly anticipated adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic fantasy left some Irish viewers cold with its depiction of Harfoots, ancestors of Tolkien’s well-known Hobbits, speaking in a blend of incongruously Irish-sounding accents and boasting such disheveled appearances that they might well have been dubbed “slobbits” instead. Perpetually muddy and with twigs stuck in their hair, these nomadic folk drag carts, poach snails and are depicted as “unwashed and simpletons,” according to one Irish reviewer.

Even Ben Allen of British GQ magazine, who said he is not easily offended, noted that the grubby characters bothered him.

“They’re Irish somehow, and they wear rags,” he wrote. “What is up with that?”

Writing in The Irish Times, Ed Power noted similarities between the Harfoots and “19th century Hibernophobic caricatures,” particularly in the “portrayal of ‘Irish’ characters as pre-industrial and childlike.” Users on Twitter noted similarities to historical distortions — which, Powers contended, also applied to the Scots.

“The Scots get it too in The Rings of Power,” he wrote, describing them as stand-ins for Tolkien’s dwarves. “It gets to the point where I expect Durin, prince of Khazad-dûm, to whip out a deep-fried Mars bar. Every other ‘mad Jock’ cliche has already been ticked off.”

The treatment of Celtic characters paralleled tropes that history has seen before, according to Power.

“Somehow the Victorian caste system has been smuggled into a 21st-century American fantasy series,” he said.

The 2020 film “Wild Mountain Thyme,” set in Ireland and starring Northern Irish actor Jamie Dornan, also succeeded in alienating Irish viewers — although the film’s stereotypes provided them with a rich source of satire. The name of the film itself derives from a song which, The Irish Times pointed out, was adapted by a Belfast man (read Northern Ireland) and “is now largely associated with Scotland.”

And What About Northern Ireland?

And here we find another conundrum. The history and culture of Northern Ireland, enriched by its vibrant Ulster Scots community, is all but invisible in films and television series, Nelson McCausland, former minister of social development for Northern Ireland, told HistoryNet.

“People broadly from Ulster, from Northern Ireland, from the broader Protestant community have very little coverage,” he said. “I can’t think of any major films that I’ve seen through the years that have really covered that community. There are plenty of films, high-profile ones, about many aspects of life in the Irish Republic, but not really about Northern Ireland other than some that are Troubles-related. But they’re not focused on that community.”

With so much diversity and the abundant variety of stories the island has to offer, making films about Ireland should not be so terribly complicated. What is going on here?

Historical prejudices

Many, if not all, of the issues facing depictions of Irishness in film are rooted in history. Negative descriptions of the Irish can be traced back as far as the 12th century, for example in an account by chronicler Gerald of Wales entitled “The Character and Customs of the Irish.” Gerald describes the Irish as “filthy,” “barbarous” and “ignorant,” among other terrible things.

Anti-Irish prejudice persisted over many years. During the 19th century, caricatures demonizing Irish people originated in “Punch” cartoons and “Harper’s Weekly,” and were circulated in both the United Kingdom and in the United States. These cartoons played a big part in creating terrible perceptions of the Irish, according to Nathan Mannion, head of exhibitions and programs at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum in Dublin.

“The cartoons always show Irish people as relatively primitive,” he said. “They’re impoverished, they’re potential thieves. Sometimes they’re anthropomorphically depicted as potatoes — that kind of thing.”

Thomas J. Scott of the University of Ulster described common negative tropes shown in early American films in his study “The Irish in American Cinema 1910-1930: Recurring Narratives and Characters.”

“Early films generally contained crude Irish stereotypes such as the ham-fisted Irish female domestic servant, drunken Irish men, buffoonish Irish laborers and womanizing Irish cops,” he wrote.

In the 1890s and 1900s, a series of silent films poked fun of an Irish servant girl dubbed “Bridget,” according to Scott, who noted that Irish stereotypes related to foolishness and drunkenness continued to be a staple of American cinema.

“I don’t think it’s a phenomenon unique to the United States, and it isn’t unique to Ireland, either,” Mannion said. “There’s a long history, for example, in Hollywood of people of Arabic extraction not being properly displayed, always being typecast as villains and so on. These are stereotypes that have existed for over a century.”

Hollywood’s Golden Age?

Even the supposedly positive characterizations of the Irish did lasting damage to their reputation abroad. These idealized depictions of Ireland and the Irish mostly came in the form of sparkling, Lucky Charms-style fantasies in films, which are a far cry from real life on the Emerald Isle.

Many mistaken perceptions about Ireland were actually created by Irish American filmmakers — notably John Ford, whose 1952 film “The Quiet Man” has become a byword for both Irish nostalgia and sheer make-believe. Though beloved by many Americans, the film irked locals in Ireland, who were “not amused by Ford’s depiction of them as drunken, cunning, capricious brawlers,” according to the Irish Independent. Another famous culprit of what has become known as “paddywhackery” was Walt Disney’s 1959 movie “Darby O’Gill And the Little People” featuring everything from fiddling leprechauns to a banshee.

Despite the over-the-top nature of such films, romanticized ideals of “the old country” on screen proved popular among Irish Americans. Filmmakers cashed in and continued to churn out movies to appeal to this large audience.

“The amount of emigration to the United States from Ireland was just immense, so you had a ready market over there,” McCausland said.

Issues Faced by Northern Protestants

Many Irish Americans involved in filmmaking during Hollywood’s Golden Age identified as Irish Republicans and also sought to appeal to the Irish Catholic diaspora. For example, Bing Crosby starred as a Catholic priest in 1944’s “Going My Way” and 1945’s “The Bells of St. Mary’s.”

Across religious and political divides, Northern Irish Protestants found themselves in a blind spot, according to McCausland.

“I think we [the Ulster Scots] were just forgotten about,” he said. “If you’re thinking of the big films about Ireland, generally, you’re talking about things like ‘Ryan’s Daughter‘ and ‘The Quiet Man.’ In both cases, there’s a connection with the IRA [Irish Republican Army] and an Irish Republican story, not an Ulster [Protestant or Unionist] story.”

Despite the Ulster Scots’ significant contributions to American history — notably fighting for American independence during the Revolutionary War — members of the Ulster Scots community have usually been portrayed as villains in cinema or simply left out, McCausland explained.

“The negativity is difficult to address,” he said.

On the subject of political division, the Troubles have been “clumsily represented” by Hollywood and rife with stereotypes on both sides of the divide, according to John Macguire for BBC Culture.

“And if the Irish haven’t been playing windswept hunks or twinkling alcoholics, they have been seen pulling on balaclavas and planting bombs,” he wrote.

‘This Is Not Us’

Stereotypes associated with Ireland haven’t gone away. There are 70 million people in the world of Irish descent, Mannion noted, including many movers and shakers credited with remarkable historical achievements. Yet when museum staff researched search engines on what the Irish were known for, they were more than slightly horrified to find that the answers that popped up involved fighting, bad tempers, drinking and potatoes.

“These stereotypes are alive and well. And they’re represented in contemporary search data,” Mannion said.

The museum launched a campaign called “This Is Not Us,” to educate the public about everything the Irish are not — with all the false Google aphorisms personified by an animated model dubbed “Paddy McFlaherty.”

Mannion said the campaign has been a great success.

“We thought there would be a little bit more division, but actually everybody was pretty much on board with the message behind it,” he said. “A lot of people are fed up with these stereotypes and see that they’re outdated and don’t consider them relevant. There’s been a good deal of humor, as well.”

Compared to the negative tropes still out there, Mannion said, Amazon’s “Rings of Power” Harfoot fumble, if problematic, is actually not too bad. The Harfoots are a fictional race, he pointed out, and are not actually intended to represent Irish people.

“It does have similarities to some of the more negative depictions from the 19th century in Ireland in terms of people who might have been victims of the Great Irish Famine,” he said. “Many of them would have been destitute and starving. A lot of them ended up as essentially refugees traveling to the United States, Canada and Britain. So I don’t think it’s ideal. But a lot of the other negative stereotypes around being violent alcoholics doesn’t seem to have been carried through into the show.”

Mannion noted that the nomadic Harfoots would “probably be closer to the Minceir or Irish traveler community, but there’s no indication that Amazon made any deliberate parallel.

“I would hope it wasn’t intentional,” he said. “I would say it’s probably an unfortunate coincidence.”

Hope for the Future?

Is there a solution to the Hollywood version of the Irish we still see today? Both Mannion and McCausland said the answer is education.

“We have a Discover Ulster Scots center in Belfast where people can come in and see the story of the Ulster Scots,” McCausland said. “One of the rooms set aside is named after a local person who was a visionary — the Montgomery room, which is devoted to telling the story of the Scotch Irish, with key points around the walls. It’s very well done.”

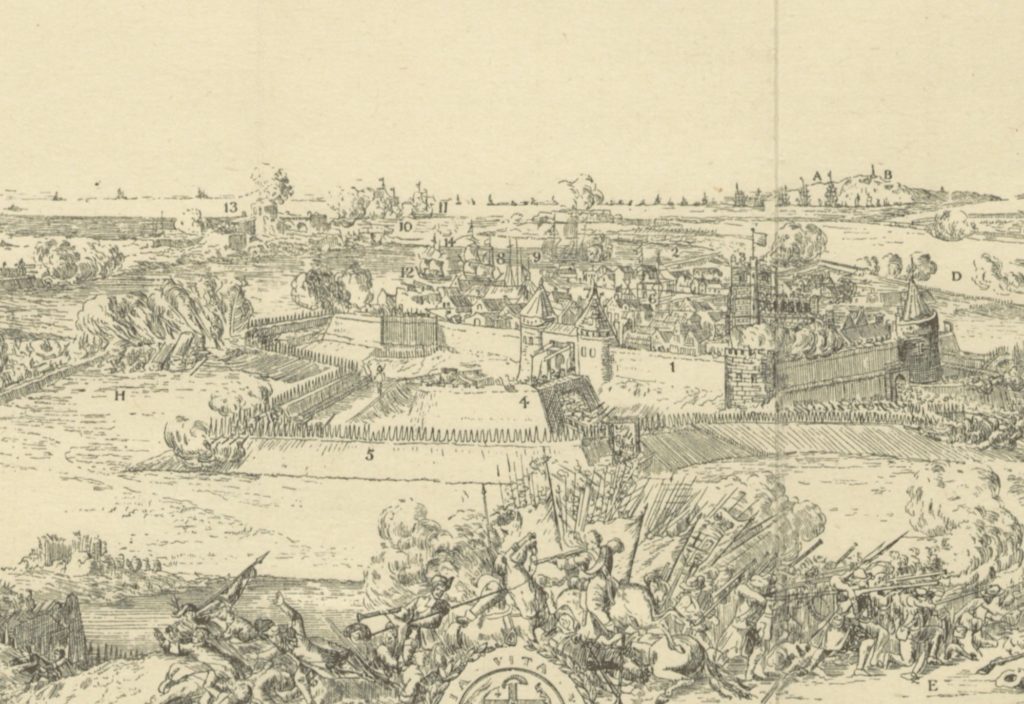

He said he hopes that the famous 1689 Siege of Derry, in which Protestant defenders held out for 105 days against the forces of Catholic monarch James II in the longest siege in Irish history, might inspire filmmakers, as well as the exploits of the Ulster Scots who fought as American patriots during the Revolutionary War.

“Telling their stories would be extremely valuable,” he said.

Mannion said that oversimplified representations of people on film can “create a distance between reality and people’s understanding.” To counter that, he and his team inform visitors to the museum in Dublin and beyond about the contributions of Irish people to the world at large.

“These tropes do recur … I suppose the only way that they’re ever going to change is if people make a principled stand against them,” Mannion said. “Some things that have been a trope for many decades have changed. There is gradual change for the better in a lot of ways.”

He offered some advice for filmmakers.

“Try to get a better understanding of what you’re hoping to depict, and if it’s supposed to be a depiction of Ireland, then does it reflect the Ireland that the people who live on the island today know and love? Or is it maybe more of a historical, rose-tinted ideal that perhaps may never have existed?

“Ask the right people the right questions, involve the experts that need to be involved and, when in doubt, go back to your source material and check with the people themselves.”

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.