Early on Nov. 4, 1979, hundreds of Iranian science and engineering students — furious that American President Jimmy Carter had granted asylum to the ailing and recently exiled Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi — descended on the chained gate and 8- to 12-foot-high brick walls of the chancery, the main building of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. Although the diplomats, staff and military personnel within the compound had every reason to be alarmed, they should not have been surprised.

Nearly nine months earlier, on Feb. 14—the same day Muslim extremists in Kabul, Afghanistan, kidnapped and murdered U.S. Ambassador Adolph Dubs — Islamic militants in Tehran had stormed the embassy. Although the invaders held the building for only a few hours, they wounded and kidnapped Marine security guard Sgt. Kenneth Krause, tortured him and threatened to execute him before officials secured his release a week later.

In the November attack the insurgents — members of a fundamentalist group calling itself the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam’s Line — had initially planned the incursion only as a symbolic show of force. “It was supposed to be a small, short-term affair,” Ebrahim Asgharzadeh, one of the leaders of the takeover, told a GQ reporter in 2009. “We were just a bunch of students who wanted to show our dismay at the United States. After that it got out of control.”

Ordered not to shoot into the crowd, the embassy’s 13 Marine security guards fired tear gas, which proved ineffectual as the insurgents scaled the walls and surged through the gates. As demonstrators arrived by the busload, the students held guns to the heads of two embassy personnel, threatening to shoot unless those inside opened the steel doors. When the inhabitants complied, the students surged into the chancery, rounding up those within. As Marine security guard Sgt. William Gallegos later remembered, “They tied us up, blindfolded us, dragged us outside.” The insurgents then paraded the 66 Americans before Iranian news cameras. For most of the hostages, it was the beginning of an odyssey that would not end for another year and 79 days.

“In retrospect,” writes author Mark Bowden in his 2006 book Guests of the Ayatollah, the embassy takeover “was all too predictable. An operating American embassy in the heart of revolutionary Iran’s capital was too much for Tehran’s aroused citizenry to bear.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Persian Past

There was nothing new in America’s presence in Iran, although others had gotten there first. The two biggest players for control of its precious oil reserves were Britain and Russia. In 1907 the two nations “split” Persia (as the country was known) into three spheres of influence, each power claiming one section with a neutral zone separating them. By forcing the economic divide, they effectively squelched Persia’s efforts to establish its budding constitutional monarchy. The following year the Anglo-Persian Oil Co. — a government-funded private enterprise that would become British Petroleum, or BP—became the first company to take advantage of the region’s oil reserves.

The United States didn’t become actively involved in Iran until World War II, when control of Middle Eastern oil was vital to an Allied victory. In 1941 newly allied Britain and Russia installed a compliant 21-year-old Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as shah, and President Franklin Roosevelt sent thousands of American troops into Iran to help run and maintain the country’s Allied-built Trans-Iranian Railway. Although U.S. troops were withdrawn at war’s end, the United States, according to Middle East historian John P. Miglietta, “began to broaden its aims in the country and the region as a whole. These centered around acquiring control of Iranian oil, as well as maintaining Iran as a strategic bulwark against the Soviet Union during the Cold War.”

The extent of American involvement in Iran became clear in 1953. The shah had become embroiled in a power struggle with Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, who, since his appointment in 1951, had nationalized the renamed Anglo-Iranian Oil Co., seized its assets and cut off diplomatic relations with Britain. In the wake of a failed August attempt to overthrow Mossadegh, the shah fled to Rome.

Later that month the new Eisenhower administration — committed to protecting Iran’s petroleum exports and concerned Mossadegh would lean on the Soviet Union for support — authorized a second joint U.S./British coup. While succeeding in restoring the shah to power, the coup claimed hundreds of Iranian lives, the popular Mossadegh was imprisoned for treason and a number of his devotees were executed. His followers never forgot or forgave America’s role in the affair. The shah continued to receive the unflagging support of each subsequent U.S. presidential administration as he continued to build a world-class arsenal for his army, at one time becoming America’s largest arms purchaser. Ultimately, the United States authorized him to buy nuclear reactors for power generation.

Ever fearful of internal dissension, the shah enlisted the CIA to help him create a secret police, domestic security and intelligence service, whose Iranian acronym was SAVAK. Described by historian David Farber as “internationally infamous for the brutality, cruelty and macabre creativity of its torturers,” the organization was widely feared, and with good reason; thousands of political dissidents — many facing torture and death — soon found themselves in Iranian prisons without having been tried.

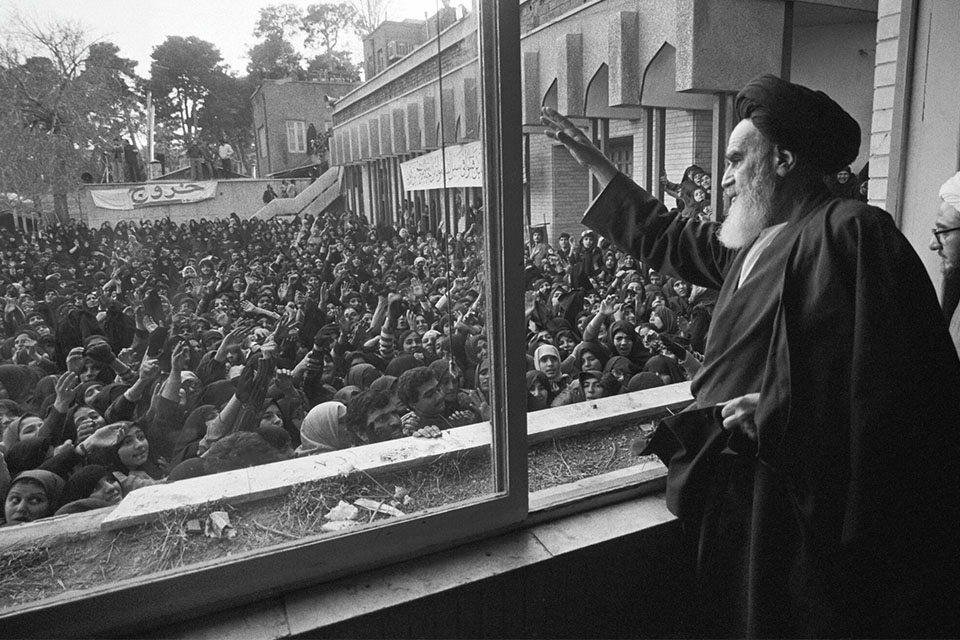

The year 1963 saw the emergence of an extraordinary fundamentalist leader in Iran. Although many Americans still regard him as a single-minded fanatic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was a scholarly, charismatic individual who combined an appreciation of ancient Persian poetry with a thorough knowledge of, and devotion to, the Quran. A Shia Muslim cleric, he gained national recognition with what writer Eugene Solomon called “a captivating moral urgency and prophetic power.” Khomeini spoke publicly and vehemently against the United States, Israel and the shah, calling the latter a “wretched, miserable man.” In 1964 the shah drove the cleric into what would become a 15-year exile in Turkey, Iraq and France.

By the late 1970s a groundswell of anti-shah and anti-American anger and resentment, combined with a growing trend toward Islamic fundamentalism, had brought Iran to the brink of revolution. Ironically, the U.S. president who became the target of decades of anti-Western resentment was arguably the most committed human rights advocate to occupy the White House since Abraham Lincoln.

Carter’s crisis

Few of even his most fervent political adversaries questioned Jimmy Carter’s good intentions. His ingrained sense of Christian morality and belief in the innate goodness of man formed the invisible plank in his surprisingly successful 1976 presidential campaign. Virtually unknown just months before the election, he won the presidency with scarcely 50 percent of the popular vote.

Carter’s term began on a positive note. A newcomer to international affairs, he held 60 meetings with foreign heads of state in his first year. His record on human rights was stellar, and he was not shy about flagging civil rights violations in other countries. “I feel very deeply,” he stated in a 1977 town meeting, “that when people are put in prison without trials and tortured and deprived of basic human rights that the president of the United States ought to have a right to express displeasure and to do something about it.” His apparently inflexible stance provided encouragement to resistance movements in such countries as Russia and Poland. As he wrote to Soviet dissident and Nobel Peace Prize recipient Andrei Sakharov in February 1977, “We shall use our good offices to seek the release of prisoners of conscience.”

In September 1978 Carter achieved the seemingly impossible. Over a contentious two-week stay at the presidential retreat Camp David, Md., he brought Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat to the peace table, alternately reasoning with, cajoling, begging and bullying them into signing the “Framework for the Conclusion of a Peace Treaty Between Egypt and Israel.” It was world-class diplomacy on Carter’s part, for which the two co-signers shared the 1978 Nobel Peace Prize.

From the beginning of his administration, however, Carter had confronted problems that, although perhaps not of his making, would prove his undoing. For one thing he had inherited a post–Vietnam War economy that was bad and rapidly growing worse. During his administration the stock market hit a 28-year low, unemployment rose, the nation’s trade deficit grew and the country experienced an energy crisis that saw gas and oil costs soar and gas station lines grow progressively longer. Carter beseeched Americans to tighten their belts and asked industry leaders to hold the line on prices and wages until the crises passed. Unfortunately for Carter, his “voluntary control” solution was not the message people wanted to hear, and his approval rating plummeted.

To exacerbate matters the president proved ineffectual in dealing with Congress. Carter could be resistant to the point of stubbornness, his strong sense of “Christian humbleness,” as historian Douglas Brinkley called it, often coming across as self-righteousness bordering on arrogance and hubris. And he often got bogged down in the details. According to James Fallows, Carter’s former chief speechwriter, “[The president] often seemed more concerned with taking the correct position than with learning how to turn that position into results.” Although serving in a government in which politicians made deals and passed bills on a give-and-take basis, Carter often refused to compromise and staunchly resisted action based on political expediency. As veteran congressman and Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill observed, “He never understood how the system worked.”

Troubled partnership

During his run for the presidency Jimmy Carter had stated, “Never again should our country become militarily involved in the internal affairs of another country unless there is a direct and obvious threat to the security of the United States or its people.” Ironically, the one arena in which that stance was seemingly absent was in his dealings with Iran.

Carter saw the U.S. relationship with the shah as a time-honored, successful and necessary one. In consideration of Iran’s proximity to the Soviet border, its position as a secure source of oil and its growing military strength in the region, Carter was willing to close his eyes to the shah’s notorious human rights violations, opting instead for a policy of what one might call “situational morality” — or to put it bluntly, lying to oneself.

During a 1977 New Year’s Eve toast at a state dinner in Tehran, Carter said, “Iran, because of the great leadership of the shah, is an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world.” Yet within a week of Carter’s televised toast, anti-shah demonstrations rocked the streets of the Iranian capital. Student protesters burned and trampled American flags and effigies of the president, and police opened fire on the protesters, killing several. Carter’s national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, later commented, “We knew there was some resentment, we knew somewhat of the history of the country, but we were not conscious, nor were we informed, of the intensity of the feelings.” As State Department spokesman Hodding Carter III observed: “Our information out of Iran was crappy to nonexistent. We had nobody who spoke Farsi, and what passed for our intelligence was what was given to us by SAVAK, since the shah, paranoid as he was, had gotten an agreement from us that we would not infiltrate Iran with our own intelligence people. The shah himself had been our chief source of information about internal dissent!”

Just over a year later, on Feb. 1, 1979, Khomeini responded to the upsurge in popular support by ending his exile and returning to Iran. Two weeks earlier the shah—weakened by cancer and faced with an army mutiny and rioting in the streets—had abdicated, leaving Khomeini the self-declared supreme leader of an Iran in tumultuous transition. Although Iranians would soon elect economist and politician Abolhassan Banisadr as the first post-revolution president, no one questioned who ran the country. On his arrival Khomeini called for the expulsion of all foreigners, and the U.S. State Department immediately evacuated some 1,350 Americans.

Khomeini’s Conundrum

Student protesters in Tehran had not consulted Khomeini prior to their Nov. 4, 1979, attack on the U.S. Embassy, and when he first heard they had taken the compound, he responded with irritation and ordered them “kicked out.” On reflection he reversed himself, seeing in the takeover a perfect opportunity to challenge the “Great Satan,” as he called the United States. It would serve to focus international attention on America’s decades-long involvement in Iran. The hostages themselves would serve as pawns, to be exchanged only when the exiled shah himself was returned for trial and, presumably, execution. Most important, it would solidify Khomeini’s power base.

From the outset of the crisis the return of the shah was a non-negotiable condition for the Iranians. When Carter had graciously allowed the shah to enter the United States that October to undergo and recover from surgery, Iranian revolutionaries suspected another coup was in the works. “The United States made a mistake taking in the shah,” hostage taker Saeed Hajjarian told GQ. “People in Iran were very sensitive to this issue. If they had not admitted him, nothing would have happened.” Carter himself appreciated the potential fallout for providing the shah refuge. After making the difficult decision, he had turned to national security adviser Gary Sick and asked, “I just wonder what advice you’re going to give me when they take our people hostage.”

Hostile Hospitality

Meanwhile, the hostages were getting a sense of what life would be like under their captors. “Eventually, they put us into rooms with 24-hour guards,” recalled embassy press attaché Barry Rosen. “We were tied up, hand and foot. You felt like a piece of meat.” Rosen noted the disturbing Iranian tendency to compartmentalize: “They’d beat the freakin’ hell out of you, and then they’d ask, ‘When this is all over, can I get a visa?’”

The captors jammed some captives into closets or locked them in dark rooms. “It was like living in a tomb,” recalled Vice Consul Richard Queen. They subjected others to mock executions, seemingly for amusement.

Less than two weeks after the attack the Iranians released 13 of the 66 hostages. Eight were Black, with whom the insurgents claimed kinship as an oppressed minority; the other five were female, freed, claimed Khomeini, because Islam respects women. The remaining 53 captives were forbidden to speak with one another, although some devised clever methods of communicating through notes and secret gestures.

With each passing day, hearing no news except what their captors fed them, the hostages grew less certain their situation was a priority back home. That Christmas the Iranians allowed four clergymen to visit the captives in a room laden with food and festive decorations. But when the holiday ended, they returned the hostages to their prisonlike conditions. “In the States,” said Roman Catholic Auxiliary Bishop Thomas Gumbleton of Detroit, one of the clerics, “the hostages were on the news every day, but they had no sense of that. They felt like they’d been abandoned.”

In late January the captors finally allowed the hostages to converse. For many of the captives time had ceased to hold meaning. “It just kept dragging on,” recalled political officer Michael Metrinko. “It wasn’t something they announced at 9 in the morning, ‘Oh, we’ve decided to hold you for 14 months.’ It just sort of drifted into it.”

IMpatient for release

Cloistered as they were, the hostages were unaware that a team of negotiators led by U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher was working for their release. The issues were complex, with far-reaching military, political, social and economic ramifications, and the negotiating process was difficult at best. “Carter and many of his key advisers seemed to really believe that Khomeini was crazy and irrational,” noted historian Farber. “They kept hoping that wiser, saner and more rationally self-interested men would take over Iran.” Forced to deal with a regime in perpetual turmoil, and frustrated in their efforts to attain an honorable settlement, the U.S. negotiators found neither clarity nor a reliable Iranian spokesperson. Deputy National Security Adviser David Aaron recalled the confusion: “Somebody would step forward and say, ‘I have the power,’ and they’d start negotiations. Then the Khomeinists would immediately say, ‘You’re pro-American, you’re selling out the revolution,’ and that person would lose their job and sometimes their life.”

The American people were in no mood to be patient. Chafing under the problems plaguing the country, many saw the drawn-out negotiating process as a further indication of Carter’s weakness. America’s reputation abroad also took a beating, as the world witnessed a small and fractious Middle Eastern state stonewall history’s strongest nation. Journalist Roger Wilkins summed up the impression: “The whole world saw these images of these people burning American flags, stomping on images of Carter, and the most rancid sort of disrespect and hatred of the United States, on television, around the world, all the time.”

By the spring of 1979 Americans had festooned trees and lampposts nationwide with yellow ribbons in remembrance of the hostages and were demanding the president bring them home. Even Carter’s wife, Rosalynn, pressured him to be more proactive. “I would say, ‘Why don’t you do something?’ And he said, ‘What would you want me to do?’ I said, ‘Mine the harbors.’ He said, ‘OK, suppose I mine the harbors, and they decide to take one hostage out every day and kill him. What am I going to do then?’”

Doomed Rescue Mission

Initially, Carter was adamant in his refusal to consider the use of force. “The problem,” he reasoned, “is that we could feel good for a few hours—until we found that they had killed our people.” Finally, however, after months of failure at the negotiating table, he concluded, “We could no longer afford to depend on diplomacy.” Against the fervid advice of Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, the president authorized a military rescue operation designated Eagle Claw and comprising a 132-man force drawn from the Army’s 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (aka Delta Force) and 75th Ranger Regiment; 15 translators; three Air Force MC-130 Combat Talon transports; three Air Force EC-130E Commando Solo tankers; two Air Force C-141 Starlifter transports; eight Navy RH-53D Sea Stallion helicopters based aboard the carrier Nimitz in the Arabian Sea; and various other supporting Navy and Air Force strike and electronic warfare aircraft.

The rescue mission was intended as a two-part operation. The first task was to establish a staging area, dubbed Desert One, at a remote location in central Iran. The MC-130s would fly in the Delta troops from an island of Oman. The soldiers would then board the RH-53D helicopters and stage forward to an assault base, Desert Two, some 50 miles outside Tehran. On the second night of the operation the Delta operators would drive overland to Tehran and assault the embassy compound. Having eliminated enemy forces and secured the hostages, the team would rendezvous with the helicopters at a Tehran stadium, airlift to the waiting transports and leave Iran and the hostage crisis behind.

Launched on April 24, 1980, the raid was an abject failure. One inbound RH-53D experienced a malfunction and put down in the desert. The remaining helicopters flew into a dust storm, which forced one to turn back and damaged the hydraulics on another. Left with just five operational helicopters, the ground element commander, Colonel Charles Beckwith, reluctantly opted to abort. As one of the RH-53Ds maneuvered to make room for a departing EC-130, it clipped the tanker’s tail and crashed into its wing root. The resultant explosion killed eight servicemen. Leaving behind the wreckage and charred remains of their comrades, the team returned home. “We left eight guys on this pyre in the middle of the desert,” recalled Delta Force operations officer Major Bucky Burruss. “That’s something you live with forever.”

Political Reverberations

Carter took full responsibility for the failed rescue attempt, his reputation suffering a blow from which it never recovered. A Time cover story titled “Debacle in the Desert” observed, “His image as inept has been renewed.” The Washington Post simply declared Carter “unfit to be president at a time of crisis.” There would be no further rescue attempts; the Iranians relocated the hostages. “They panicked and spread us all over the country in 48 hours,” recalled embassy military attaché Joseph Hall. “I think I was moved 17 times during the next two months.”

On July 11, the 250th day of the crisis, Vice Consul Queen joined the 13 other released hostages after a doctor discovered he was suffering from multiple sclerosis. That left 52 in captivity. With the threat of military action off the table, their only hope for release was successful diplomacy.

Sixteen days later the shah died in an Egyptian hospital. Since his return was the primary condition for release of the hostages, many in Washington hoped his death would end the ordeal. But there was no change in the Iranian stance.

Election Day that year fell on November 4, the anniversary of the embassy takeover, a coincidence that further highlighted Ronald Reagan’s landslide victory. Carter then faced a tight deadline if he was to affect a release of the hostages in what remained of his single term in office. In early January 1981, in accords brokered by Algerian mediators, the parties reached a satisfactory, if not mutually agreeable, resolution. Among other humiliating concessions, American negotiators pledged the United States “would not intervene politically or militarily in Iranian internal affairs” and agreed to release nearly $8 billion in Iranian assets frozen by Carter at the outset of the crisis. Christopher signed the accords on Jan. 19, 1981, Carter’s last day in office. All that remained was for Iran to honor its part of the deal.

Final Hours

In those final hours in the White House, Carter and his senior advisers stayed up all night in the Oval Office, waiting for the call announcing the release of the hostages. Morning would see the swearing-in of Reagan as 40th president of the United States, and Carter wanted the satisfaction of knowing the 52 long-suffering American hostages had been released on his watch.

It was not to be. Only after Reagan had taken the oath of office and completed his inaugural address did an airliner carrying the hostages leave Tehran bound for West Germany. It was the ultimate slap in the face to the man who had labored tactfully—and ultimately, successfully—for 14 months for the release of his countrymen.

It then fell to Reagan to announce the release of the hostages and to bask in the resultant patriotic glow. To many observers the hostage crisis marked Carter’s last failure as president, and Reagan’s first success, albeit unearned. Neither he nor any of his transition team had participated in negotiations, nor did Reagan initially credit the outgoing president for the hostages’ release. The American people, however, could finally untie their yellow ribbons and breathe a collective sigh of relief. After a harrowing, humiliating and seemingly endless wait, the hostages were home.

Many REvolutions

What neither Carter, nor his advisers nor the American people realized was that the Iran hostage crisis was not simply a one-off event engineered by a religious fanatic. History is nothing if not a continuum, and students of history might well trace a direct line from the street revolutions of the late 1970s to the Arab Spring of the 2010s and ultimately to the terrorist organizations currently rampaging throughout the world. Although the United States hadn’t met all their conditions, the ayatollah and his followers considered the hostage crisis and resulting accords a success. After all, they had demonstrated that a small group of unswervingly committed believers with limited resources could hold the world’s most powerful nation hostage for an extended period of time, and they had done so on a global stage. It is a lesson the United States seemingly has yet to learn.

Freelance writer Ron Soodalter is the author of “Hanging Captain Gordon.” For further reading he recommends “Guests of the Ayatollah: The Iran Hostage Crisis: The First Battle in America’s War with Militant Islam,” by Mark Bowden; “American Hostages in Iran: The Conduct of a Crisis,” by Warren Christopher, et. al; and “Taken Hostage: The Iran Hostage Crisis and America’s First Encounter with Radical Islam,” by David Farber.

First published in Military History Magazine’s March, 2017 issue.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.