‘I’ve done all the research on the D-Day book I’m writing, and I’ve got artifacts,’ said Steve Ambrose. ‘Let’s create a small museum’

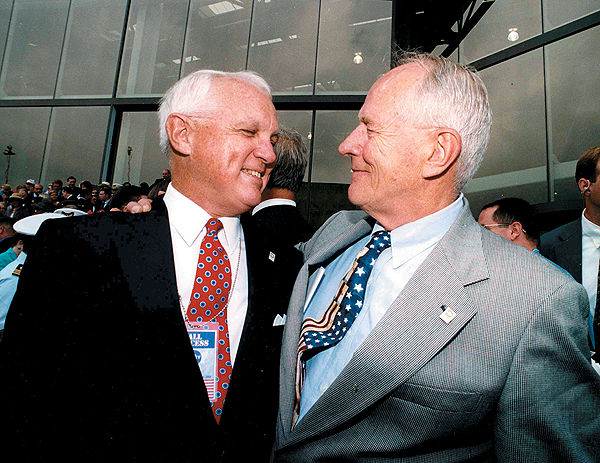

Gordon H. “Nick” Mueller is president and CEO of the National WWII Museum in New Orleans, La. But his ties to the museum go far deeper than title. He shepherded the project from its 1990 conception to its June 6, 2000, opening. Mueller tended the museum through Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and into its current multimillion-dollar Road to Victory capital expansion campaign, which will quadruple the size of the original center. It all started as a backyard chat with his best friend, historian and fellow professor Stephen Ambrose. Mueller came to the project from a three-decade career at the University of New Orleans, where he taught European history, served as a dean and the vice chancellor of extension, and launched the university’s research and technology park. He is uniquely qualified both to run the museum and to relate the events of the greatest conflict in human history. Mueller recently spoke with Military History about the museum and his vision for it beyond planned events marking the 70th anniversary of the Normandy invasion.

What prompted you to leave the relative security of academia to launch a national museum?

In 1990 the university asked me to develop its research and technology park on a 30-acre site across from the campus. One afternoon at the beginning of that process Steve Ambrose said to me: “You’re doing this research park, and you’ve got land. I’ve done all the research on the D-Day book I’m writing, and I’ve got artifacts.” He had taken about 600 oral histories, personal accounts of the D-Day invasion from the airborne, the Navy and the guys who went in to the beaches. They’d send in their oral histories and a related artifact. He had parachutes, weapons and everything all over his office. “I don’t know how to take care of all this, so let’s create a small museum.” That research park site happened to be on Lake Pontchartrain, where Andy Higgins had tested his landing craft [LCVP, or Higgins boat].

“Besides,” Steve said, “I’ve been talking to congressional leaders for 15 years to do a D-Day museum to honor these guys and preserve that story. They all say it’s a great idea, but nobody ever does it. So let’s do it right here.”

How extensive a museum had you envisioned?

Very modest. Steve thought it would be a million bucks. “It’s going to be at least $4 million,” I told him. We created a nonprofit foundation, brought in museum designers, architects, consultants. Ten years and about $30 million later we were downtown instead of on the lakefront. Lots of ups and downs in between; we went broke twice. But we finally prevailed. We opened as the National D-Day Museum on June 6, 2000.

When did the focus shift to encompass all of World War II?

The impetus came from Congress, from two war heroes: Senators Ted Stevens, from Alaska, who had the Distinguished Flying Cross, and Daniel Inouye, from Hawaii, who had the Medal of Honor. Both said, “Washington is never going to get around to a World War II museum”—exactly what Steve had said. “We’d rather help you enlarge this museum to tell the whole story of the war.”

What was your reaction?

Well, we agreed, but we were pretty much exhausted and knew what an undertaking that would be. Steve kind of rolled his eyes, looked at me and shrugged. “Well, why not?” he said. “Let’s give it a shot. We did this; we can maybe do that.” [After serving on the museum board as founder and distinguished historian, Ambrose died in 2002.]

What role did Senators Stevens and Inouye play?

They got us $12 million [in earmarks] over about three years that enabled us to buy the land we needed—three blocks of property across from the museum, filled with rundown warehouses—and to do the master planning.

In 2004 we came to Washington with Tom Hanks and had a big kickoff of the capital campaign, which according to the master plan would take us until 2012. We were going to have to raise a bit north of a couple of hundred million dollars, so it seemed ambitious—a lot more than two history professors having drinks.

A year after we announced this ambitious expansion, Katrina hit, and that really kicked us in the ditch.

How bad were things?

The city was totally flooded, empty of inhabitants—much less tourists—for almost a year, and we had to make a decision about going forward or not, and, if so, how would that look? It was probably the most challenging moment in the evolution of this institution, because we had yet to build anything as part of this new expansion.

I had to lay off about 60 percent of the staff. We had no security, no custodian—just a handful of professionals. We all had shifts at cleaning the floors, the toilets. And National Guard members were the only people coming to the museum. But we got open. That was my first objective.

What about the master plan?

The museum board wanted me to offer different scenarios, so I gave five—the first to cancel it completely, the fifth to do everything as originally conceived. I picked No. 3, which was to continue the master plan but eliminate some of the cost—reduce the size of some buildings, cut one out. I also requested to move the target date back to 2015.

“This is tough,” I told the board, “but it’s not like landing on Omaha Beach. There’s nobody shooting at us. If it takes us a bit longer, so be it.” And that’s what we agreed to do. We had some good fortune after a year or two—commitment from major private donors, a big federal gift and the benefit of the new market tax credits. We opened the first phase of the expansion in 2009.

What will a visitor find now?

When you walk in the door, you’ll get a dog tag with a microchip of a soldier’s, sailor’s, Marine’s or airman’s personal oral history. Next, you’ll board a 1940s Pullman train car, with film footage of the countryside, the towns of America, passing by the windows. That’s where you’ll swipe your dog tag and find out whose story you’re following. You can swipe it again at other exhibits and find out what this soldier was doing on D-Day or Guadalcanal or wherever he was.

The next big attraction is Beyond All Boundaries. Tom Hanks and Universal Studios worked with us to create this 4D impressionistic journey through World War II, from one side of the world to the other, in about 50 minutes. People come out of the theater stunned, with a sense of the scope of the war.

Then you’ll have choices. You can go into the Normandy exhibit, or do the Road to Berlin, the Road to Tokyo or the Home Front. You’ll end up at the U.S. Freedom Pavilion: The Boeing Center, a spectacular, high-volume building with a suspended B-17, a B-25 and five or six other planes; a Medal of Honor exhibit with the faces of all 464 recipients from World War II; and a literally immersive submarine experience, the story of the final mission of USS Tang.

What is your favorite aspect of the museum?

That single artifact that communicates what a person went through—one that connects you to the citizen-soldier and to the strength of the American spirit—that really is the signature of this museum.

Has it been worth all the effort?

This museum covers one of the epic invasions of Western civilization. It’s a big story, and we have a tremendous responsibility to tell it right, with the very best historical advice and leading experts. World War II will be an endless source of exploration and discovery and knowledge, and I’m glad to be a part of the beginning of the ride.

What would Ambrose have thought of the museum?

I think if Steve came back to Earth, he’d probably look around and think he’d died and gone to Heaven!