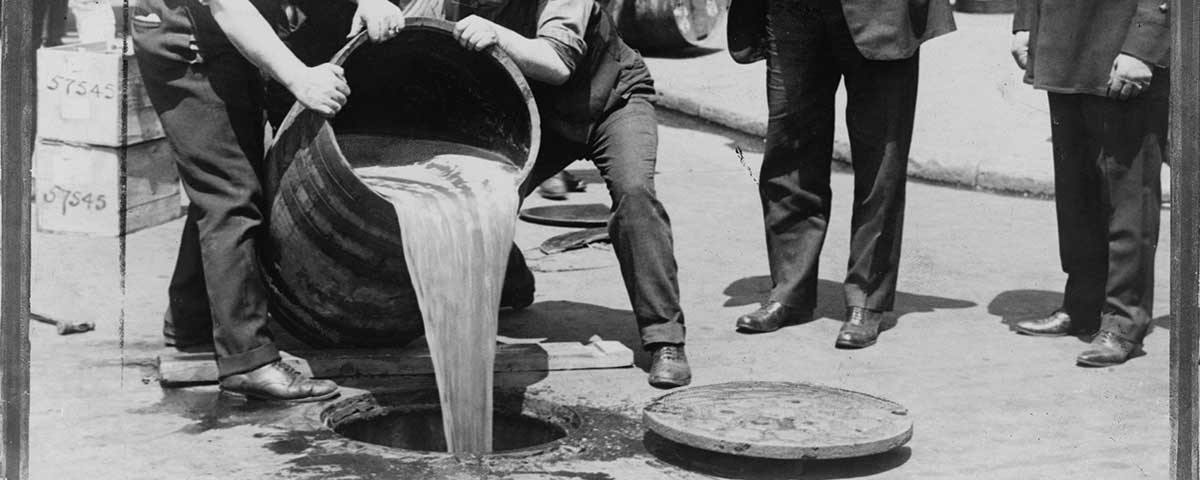

Over the past 30 years, Ken Burns has made 20 documentary films about American history, including The Civil War, Jazz, Baseball, Brooklyn Bridge, The National Parks and The War, as well as film biographies of Thomas Jefferson, Huey Long, Thomas Hart Benton, Jack Johnson and Mark Twain. Shown repeatedly on public television, his films have been seen by millions of people, making him easily the most popular historian of our time. His latest documentary, created with his longtime co-producer Lynn Novick, is Prohibition, a three-part, six-hour study of the so-called noble experiment that made alcoholic beverages illegal in the United States from 1920 to 1933. Prohibition will air on PBS stations in early October.

What prompted you to make a film on Prohibition?

It’s a story running on all cylinders. It’s just a great American story that reveals ourselves to ourselves in ways that are endlessly entertaining, disturbing, funny, dramatic, violent and sexy.

What does it reveal about us?

The thing that was so striking to me about this project is how contemporary it is. If you stripped away the title Prohibition and just talked about the themes it engages, you’d think we were working on a contemporary subject, like the Tea Party or nasty political campaigns or the demonization of immigrants—a lot of themes we see today. Prohibition was based on the notion—extremely optimistic on our part—that the government can fix anything. It was born out of the mistaken idea that alcohol by itself was the sole cause of so many problems in society that its elimination would turn us into that bright shining city on a hill. In fact, there were tremendous unintended consequences—turning half of America’s citizens into lawbreakers, the creation of heretofore nonexistent organized crime that is still with us today. It’s just an irresistible story.

It seems incredible that the prohibitionists actually managed to ban alcohol. How did they do it?

It happened because the Anti-Saloon League made prohibition the most effective single-issue campaign in our country’s history. And they went at it with they called “concentrated vigor.” They didn’t care if a politician was a Republican or Democrat. If you believed in prohibition, they would work for you. If not, they would work to defeat you. And there was an anti-immigrant component—it was small town Protestantism versus big city Catholicism. When you add World War I to that, you’ve got a perfect brew—no pun intended. You’ve got the United States government saying the Hun is the enemy abroad, but we also have enemies here and their names are Schlitz and Pabst and Blatz and Miller—a lot of German names among these brewers.

Do you see parallels with the contemporary war on drugs?

We went into this film assuming there would be sort of daily reminders of the war on drugs. And while there are obvious parallels, we really felt there wasn’t as direct a connection as people try to make. Alcohol has been around in most cultures as long as people have been human. Drug use has also been around for millennia, but it has been a sub-cultural event. It’s not the same thing. But we love the idea that the film will promote these kinds of conversations.

You made your first movie, Brooklyn Bridge, 30 years ago. When you look at it now, do you think you should have done anything differently?

I look at it the way I look at my oldest child—she’s perfect, but also not.

Why have you always made your films for public television?

It’s the environment where we can concentrate on making the best film we can make without marketplace-driven anxieties. It takes years for us to do a film and only public television can do that. The History channel just doesn’t spend that much time or dive that deep.

We live in an age of short attention spans. But your movies play over many hours on several nights. Why?

All meaning accrues in duration.

Is that a quote from somebody?

It’s a quote from me. (laughs) All meaning accrues in duration. I believe that. I suggest that the work you most care about, and the relationships you most care about, have benefited from your sustained attention. The person you met two seconds ago is not the person you’re in love with. It might take you 30 or 40 hours to read a good book. You know, 21 years ago, I was told by television critics that nobody would watch The Civil War because Steven Bochco’s new musical drama Cop Rock was going to blow us out of the water. Well, Cop Rock was cancelled mid-season, and 40 million people watched The Civil War. If it’s something people care about, they’ll pay attention.

How do you pick your topics?

The projects choose us. We don’t have clients. These are not mercantile exercises. We’re not asking what will sell. We’re drawn to things that interest us. There are a handful of us and we talk about it, and then commit to doing it. And what is so fortunate is that we’ve never exposed a foot of film on a project we had to abandon. We’ve made every film we started to make.

I hear that your work life is plotted out for the next decade or so.

We know what we’re doing until 2019. We have a film we’re going to lock next week on the Dust Bowl. We’re beginning early editing on a film about the Central Park jogger case. We’re halfway through editing a big major series on the Roosevelts—Theodore, Franklin and Eleanor—that will be out in 2014. We’ve just begun filming a biography of Jackie Robinson. We’re deep into a project on Vietnam, a huge series on that. And we’re also doing a history of country music, which is unexpected and different and filled with hugely complicated stories. And a biography of Ernest Hemingway.

Is there a negative side to knowing what you’re going to be doing so many years from now?

Yes: It doesn’t permit you to say yes to something that comes along. But we say yes anyway. The Jackie Robinson project was shoehorned in. But we’re utterly dependent on grant funding, and it takes years to raise the money. The projects I just mentioned total more than $90 million. I’m still raising money for that last project, the Hemingway film.

Are you still involved in every aspect of every film?

No. I can’t be. I used to be involved in absolutely everything. I would shoot every shot. But after awhile you can’t do everything. What I haven’t given up is the ultimate voice in the editing room because our films are made in the editing room. We have remarkable interviews, remarkable footage, remarkable stills, but how they get put together is really important. At the end of the day, somebody says yes or no and I reserve that right.

Do you have any desire to make a film that doesn’t look like a Ken Burns film?

Why? Would you ask that of Cezanne? Would you say, “Are you thinking about doing pop art next, Paul?” You can only do what is authentic. If you’re just changing for the sake of change, that’s not anything but fashion. And fashion has a cold center. There’s nothing durable about it, because the next season, it’s out of fashion.