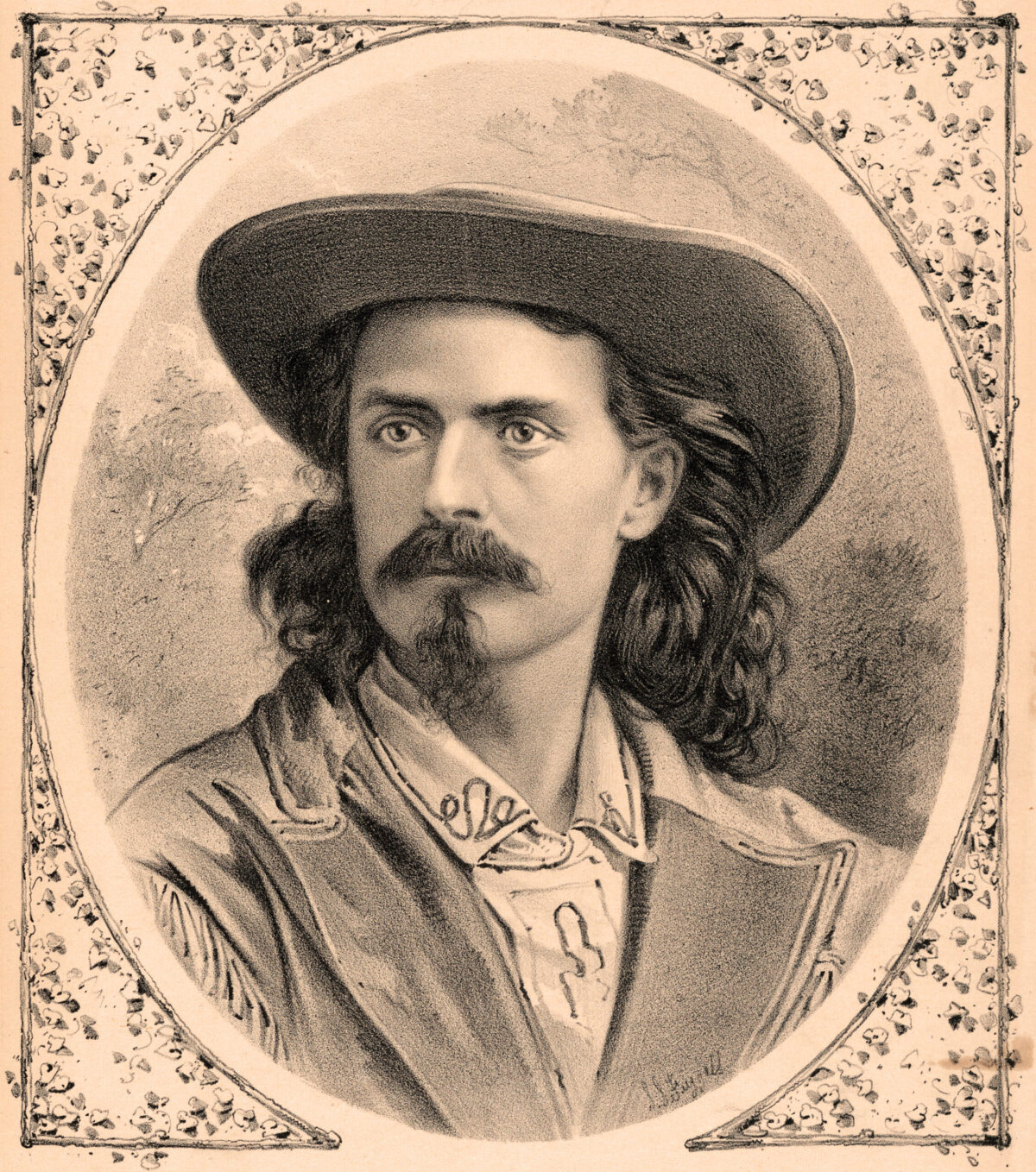

Just about every student of history knows that William F. Cody brought the Western story—or, at least, its myth—to millions of fans worldwide with his Wild West exhibitions. Yet before those shows began in 1883, Cody had entertained theatergoers in stage plays across the United States. Granted, Cody would never be mistaken for one of the leading actors of the 19th century, but the plays—with titles such as Scouts of the Prairie,King of the Border Men, Red Right Hand and The Prairie Waif—all starring Buffalo Bill as himself, were smash hits from Akron to Zanesville. Cody was so smitten with his life as an entertainer that he once told a newspaper reporter, “I’m no d____d scout now; I’m a first-class star.”

Historian Sandra K. Sagala first tackled Buffalo Bill’s thespian enterprises in Buffalo Bill, Actor: A Chronicle of Cody’s Theatrical Career, published in 2002 by Heritage Books. She has updated, expanded and reworked that volume with Buffalo Bill on Stage, published in 2007 by the University of New Mexico Press. Sagala discussed Cody in a recent interview with Wild West Magazine.

What drew you initially to Buffalo Bill’s theatrical career?

When I wrote to Joseph Rosa, Wild Bill Hickok’s biographer, about Hickok, he wondered if I’d research the months Hickok toured with Cody. That was the start of it all.

Could there have been a Wild West exhibition had Cody not begun onstage?

Many other Wild West shows, like Doc Carver’s, were started by men with no theatrical background. You don’t hear much about them, because Cody’s was the best. Was that a consequence of his dramatic experiences? Absolutely.

How did this rugged frontiersman first come to tread the boards?

Cody was well known as an Army scout and experienced hunter. After a successful hunt with Easterners, they invited him to visit New York City, where Ned Buntline’s story “Buffalo Bill, the King of Border Men,” now dramatized, was playing. When the audience learned the real Buffalo Bill was in the theater, they urged him onstage. Frightened, Cody just stood there; nevertheless, the manager offered him $500 to play himself. He refused, but Buntline pestered him until he relented.

How about the reviews? Good, bad?

Mixed. Occasionally critics in the same city reviewed the play from disparate viewpoints. One claimed the drama was the very best, not to be missed. The other judged it poor, the actors likewise.

How about an example or two of, ahem, the more blunt bad reviews?

How about “ludicrous beyond the power of description” or “everything was so wonderfully bad that it was almost good”? Also, “[the drama] is composed of a score of impossible situations, and the dialogue is disjointed and bad.” And this one, “There is a slender thread of a plot, which fails, however, to give the piece sufficient continuity to enable the observer to remember, having left the theater, what it was all about.”

But the plays were a huge hit?

Cody made a lot of money during his tours; one year he profited $50,000 after expenses. There were facetious reports of a theater’s wallpaper being removed to make room for all his fans.

Why did Cody and Buntline part company?

Buntline had an unsavory past. Also, Cody and Texas Jack [Omohundro], his acting partner, spent freely throughout the first season, so end profits disappointed. After blaming Buntline, they decided they could manage better on their own.

And that brought in other co-stars, including, briefly, Wild Bill Hickok. What struck you about that 1873–74 season?

What a troublemaker Hickok was. He thought they were making fools of themselves, and whether out of boredom or mischief, he’d pull pranks on the troupers, causing headaches for Cody.

Who were his other co-stars?

Texas Jack, Giuseppina Morlacchi, Kit Carson Jr., Jack Crawford.

How did those players work with Cody?

Texas Jack, Cody’s fellow scout, was eager to join him in his first experience as actor. Their naiveté created a bond; they were both so ignorant of theatrical life. After Buntline hired Mademoiselle Morlacchi to play the Indian maiden role, she and Jack fell in love and were married. Kit Carson Jr. was not the son of the great scout; discovering his true identity kept the press busy for the entire season. To increase his stature, Cody billed Carson as a Texas Ranger. He was not. Jack Crawford was, perhaps, one of Cody’s most difficult partners. They fought over Jack’s salary and the logistics of bringing horses onstage. After a shooting accident in Virginia City for which Jack blamed Cody, he split, and the two men were enemies thereafter.

Overall, what was Cody’s relationship with his fellow actors?

While he was working with them, the affiliation was fine. Too soon, though, several co-stars got “big heads,” thinking they could manage a troupe on their own. When they couldn’t, they hoped to return. That’s when Cody got upset with them.

And with his family during this period?

Early on, Cody moved his family East so they could be on the same coast where he was touring, but he saw little of them.

Who wrote Cody’s plays?

Ned Buntline, Prentiss Ingraham, Hiram Robbins, John Stevens, Andrew Burt.

Buntline and Ingraham, of course, helped further fuel Buffalo Bill’s image in dime novels. What distinguished these writers?

While his plays were bad, if it weren’t for Buntline’s insistence, Cody would have never considered a stage career. Robbins helped manage Cody’s troupe and wrote a drama during their travels. Burt was a career military man whom Cody probably met at Fort Laramie during his scouting days. Burt’s experiences qualified him to write authentic dramas about the frontier. Successful playwright and theater manager Stevens authored Cody’s most popular play, The Prairie Waif, and charged the most for it. Ingraham was a Southern gentleman whose style of writing about cowboys thereafter influenced how they acted and dressed. More than 200 of his 600 novels and 400 novelettes featured Cody as hero.

How difficult is it to discern the plots of these plays without surviving copies?

Some seasons’ programs contained phrases from the plays, which provided plot points, but without seeing the performance, it’s quite difficult to figure out who’s doing what. Other programs only supplied actors’ names and scene titles.

In some plays, Cody addressed “current affairs” out West, such as John D. Lee and the Mountain Meadows Massacre. What were his reasons?

After a 20-year delay, John Lee’s 1877 execution for the massacre was back in the news. Mormons, quite unpopular with Americans at the time, made great villains not only for dramas but also for any kind of literature.

Was the successful five-act drama First Scalp for Custer a case of life imitating art or vice versa?

During his foray as Army scout in summer 1876, Cody killed and scalped an Indian named Yellow Hair—in revenge, he said, for Custer’s death. The next theatrical season, Cody commissioned a play about the event. That Yellow Hair had nothing to do with Custer didn’t matter.

The plays actually overlapped with his Wild West for a while. Why did Cody end his acting career?

When he added Indian songs and dances, marksmanship exhibitions, live animals and an increasing number of actors to the performance, the drama simply outgrew any stage’s limitations.

Did your opinion of Cody change during the course of your research?

From his initially being just a research subject, Cody grew into someone I really like. His progression from stage-frightened frontiersman to world-renowned showman was wonderful to follow.

What would you say is the legacy of these stage melodramas?

All you have to do is observe Cody’s selfconfidence as master Wild West showman to see it.

Anything else?

If anyone reading my Appendix II can verify cities/dates that remain questionable, I’d like to hear from them through UNM Press [www.unmpress.com].

Originally published in the February 2009 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.