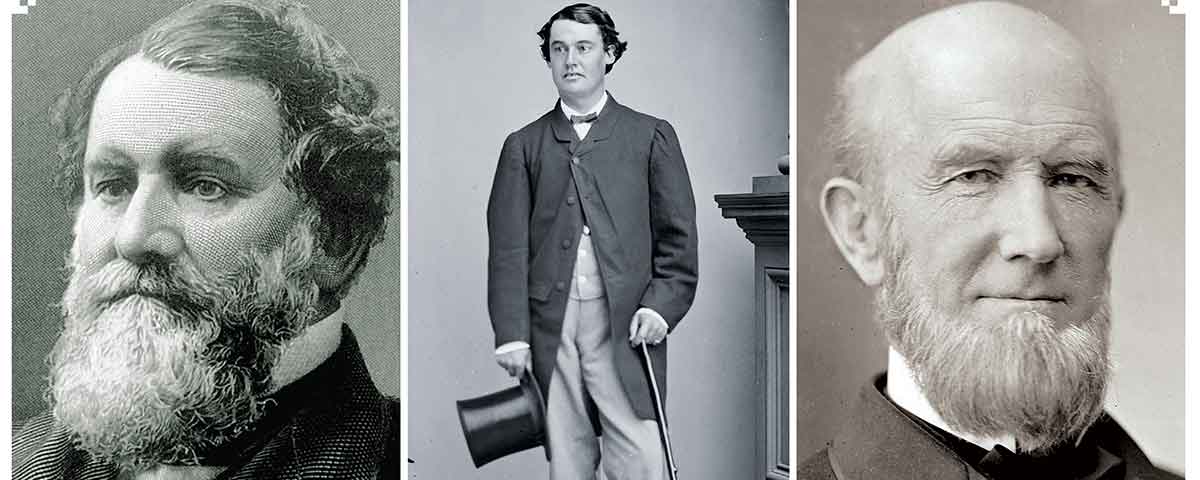

Mosby, Custer, and Lee have been the focus of some of Jeffry Wert’s previous nine books, but in his latest volume he leaves the front lines to take a larger look at the conflict: men who created businesses that helped the Union to victory. Civil War Barons (Da Capo Press) profiles 19 businessmen and inventors, including Cyrus McCormick, who made his name selling an implement that so revolutionized grain harvesting that men could afford to leave their fields to join the Union Army. Several other figures created brands that last to this day: timberman Frederick Weyerhaeuser, inventor John Deere, canned-milk innovator Gail Borden, pharmaceutical giant Edward Squibb, and shoemaking pioneer Gordon McKay.

You open the book with Jay Cooke. Why?

He’s the revolutionary who changes the way the United States finances wars. It’s certainly true in WWI and WWII. He is the one who links self-interest, or personal profit, to patriotism. And that’s how he sells war bonds during the war.

What did he do?

He sold bonds, initially in Pennsylvania. When it came to a national issue of bonds and representing the government in the sales, he sent out at one point 2,500 sales reps. He made bonds with lower denominations where ordinary people could buy a bond, and in turn they had a stake in the fight. He put bonds down as low as $50. A group in Philadelphia would all buy weekly and put their wages into buying a bond, for example. That was unheard of. He made war bonds available to ordinary Americans and at the same time he tried to convince them that you will help save the Union and make a profit while doing it.

One of an army’s basic needs is shoes. Talk about Gordon McKay.

Gordon McKay bought the rights to a machine invented by Lyman Blake that sewed shoe or boot uppers to their soles. When the war came, he sold the machines to shoemaking factories in New England. The estimate is that half of the shoes and boots worn by Union soldiers were sewn by the McKay stitcher. He took a royalty on each shoe or boot made. Before he died, he willed the vast amount of his estate to Harvard University and it sustains 40 scholarships and fellowships in their engineering department.

Horseshoes were also critical.

Henry Burden, a Scottish immigrant, ends up in Troy, N.Y. In 1830, he invented a machine to cast or forge horseshoes. By the time the Civil War comes, he had gotten it down to a one-step process for casting the shoes. He ended up being able to produce a horseshoe a second—and sold 70 million horseshoes to the Union government. Astonishing numbers. An archaeologist told me that during the 1864 Shenandoah campaign, when the farriers would re-shoe Union cavalry horses, they would take those horseshoes and cut them in half and bury them in separate piles so the Confederates couldn’t find them. That’s how critical it was.

Some of the Union success relied on industrial espionage. Tell us about Abram Hewitt.

Abram Hewitt went to Columbia on a scholarship and ended up tutoring Edward Cooper, the son of Peter Cooper, a wealthy inventor who formed the Trenton Ironworks in New Jersey. When the war began, Edward Cooper and Abram Hewitt were running the ironworks to produce gunmetal for rifle barrels, but the Springfield Armory rejected them. The best gun barrel metal in the world was created in England and Germany, so he went to England to ask the leading manufacturers if they would give him their secret formula. They told him no. So he trolled the local pubs and found out from the workers what the formula was, came back, and produced with that formula, which was acceptable to the Springfield Armory.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”right”]Half of the shoes and boots worn by Union soldiers were sewn by the McKay stitcher[/quote]

They also offered to turn one of his leading factories over to the government. Hewitt said that in times like this service means far more than profit. But the government rejected the offer, so what they did was charge enough to cover cost and make a little bit of profit. After the war, Hewitt becomes the mayor of New York City.

A key contributor to Union success had Confederate sympathies. Tell us about Cyrus McCormick.

He and two brothers, William and Leland, were Virginians, but by the time the war comes, they had relocated from Rockbridge County, Virginia, to Chicago. But the McCormick brothers’ reaper was important to the Union victory. Even the secretary of war acknowledged its role: the reaper, with its increased grain harvesting efficiency, allowed men to leave the farm and join the ranks of the army. If you read their letters and papers during the war, all three brothers wanted some kind of political solution that allowed a separate Confederate nation. The McCormicks end the war very rich, but they are clearly torn.

Tell us about Edward Squibb.

He was a doctor in Philadelphia, a Quaker, who became a Navy surgeon. During the 1850s, he produced more pure forms of ether and chloroform. During the war, he continued to work on that. Investor friends gave Squibb money and he formed laboratories that became Squibb Pharmaceuticals. His work saved many men from the pain of surgery. He also produced what is known as the pannier, a medical box used by many surgeons during the war. Squibb was more concerned with saving lives than making money.

Is there someone you would like to highlight?

James Buchanan Eads. Remarkable mind, a self-taught engineer, he made a fortune before the war by creating a device that allowed people to walk on the bottom of a river and salvage sunken ships. When the war comes, he designs gunboats that will be used in the Western waters, in the key campaigns of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson.

Which characters had the biggest impact on the course of the war?

Henry Burden did, in serving the critical need for the horseshoe. You can make a good case for Christopher Spencer—the quiet little Yankee, as Lincoln secretary John Hay calls him—and the repeating rifle he designed. He was just given a dollar a weapon as his share. Of course, Jay Cooke. And I believe the McCormick reaper was critical to Union victory.

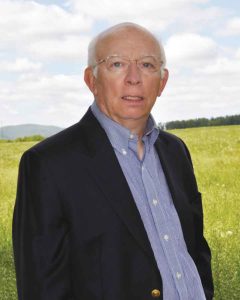

Interview conducted by Senior Editor Sarah Richardson