Students are inspired to think deeply about history when they visit historic ground

Civil War Battlefields bring the past vividly to life. Walking these sites enables us to make a connection with earlier Americans that cannot be duplicated in a classroom or anywhere else. I have taken students to Antietam, Gettysburg, Chancellorsville, Bull Run, Petersburg, Cedar Creek, and other sites for more than 30 years, and the experience has proved singularly effective in helping illuminate 19th-century attitudes and motivations.

I want to focus on Antietam to illustrate how battlefields resonate with students. Readers of Civil War Times, unlike many undergraduates when they begin my classes, know that Antietam, fought on September 17, 1862, closed Robert E. Lee’s first invasion of the United States and produced approximately 23,000 casualties. My students and I follow the battle chronologically during a six-hour walking tour. Traversing the field enables them to understand the tactical ebb and flow. I take them to the hill east of the National Park Service visitor center to set up the campaign, then proceed around the battlefield with stops at the Dunker Church, the Joseph Poffenberger farm near the North Woods, the southern edge of D.R. Miller’s cornfield, the West Woods, the Sunken Road, Burnside Bridge, and the National Cemetery. While examining the tactical action, I point out other landmarks such as Nicodemus Heights and the ridge where the Pry House sits above Antietam Creek.

Because the battlefield offers a tangible link to a watershed event in our history, students easily move from specifics concerning leadership and combat to larger questions. Did the founding generation envision a true nation or a collection of semi-autonomous states? Why was emancipation added to restoration of the Union as a goal for U.S. armies? How did events on the battlefield influence morale behind the lines? Were the soldiers in the two armies more alike than different? How did women such as Clara Barton, who made her first major appearance at Antietam (though not where her monument stands), overcome obstacles to play a significant role in a conflict too often seen as overwhelmingly the province of men?

Antietam is especially useful to explore how the military and nonmilitary spheres intersected. For example, I talk about the battle’s importance in giving Abraham Lincoln the opportunity to announce his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. I examine the nature of the proclamation, its relationship to congressional actions such as the Second Confiscation Act, and the shift in historical analysis regarding emancipation from a preoccupation with political events in Washington to a more complex interpretation that considers actions by African Americans—both enslaved and free—as well as the essential role of Union military forces.

Antietam also provides a good place to discuss the diplomatic implications of military events—how England and France backed away from some type of mediation in the American war following Lee’s retreat. I point out that as the armies maneuvered and fought in Maryland, British Prime Minister Palmerston and Foreign Secretary John Russell agreed to try to broker a cessation of hostilities if Lee added a third victory to those at the Seven Days and Second Manassas.

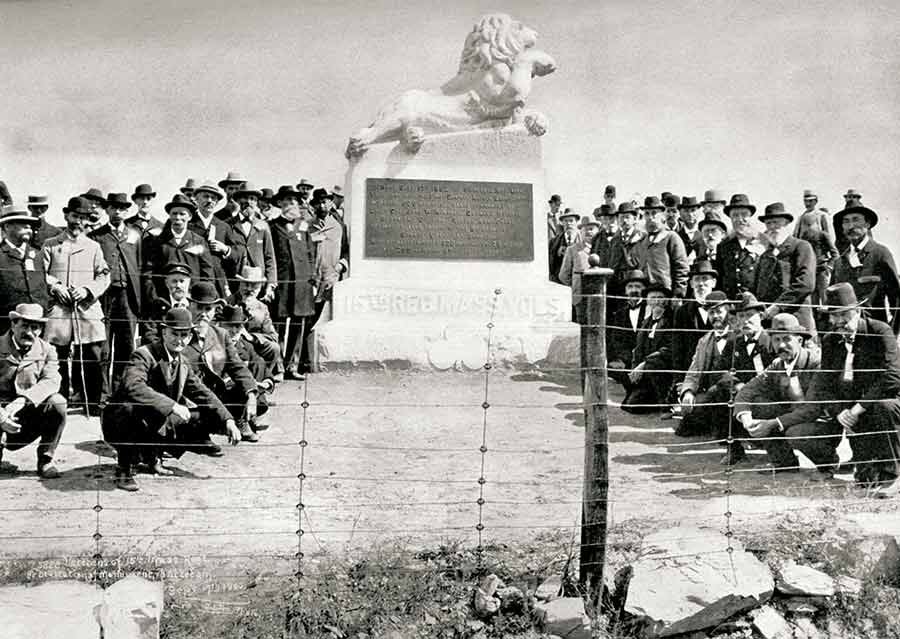

Although no student has prodded me to talk at greater length about diplomacy, many have asked about burial practices. I address that question at the 15th Massachusetts Infantry’s monument at the western fringe of the West Woods. I show Henry W. Ainsworth’s name on the monument, listed with eight others in Company H killed on September 17, and read what a comrade wrote to Henry’s father. “I went down to the front of the wood, and…found a burying party from the 15th….But I was too late, he was buried.” Henry’s body was in a trench “25 feet long, 6 feet wide and about 3 feet deep.” The trench contained two layers of dead soldiers: “The bottom tier was laid in, then straw laid over the head and feet, then the top tier laid on them and covered with dirt about 18 inches deep. Henry is the 3rd corpse from the upper end on the top tier next to the woods.” After this precise description, Henry’s friend added, “Mr. Ainsworth, this is not the way we bury folks at home.” As I read this letter and point to Alfred Poffenberger’s cabin, near where Union soldiers dug the trench, students invariably grow very quiet.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]I have seen hundreds of students benefit from walking battlefields[/quote]

Other monuments also have great interpretive value. At the Maryland monument, near the junction of the Hagerstown Pike and Smoketown Road, I discuss factors that led four slaveholding states to remain in the Union while 11 others seceded. At the 132nd Pennsylvania’s monument beside the Sunken Road, I talk about that outfit as typical of the green 9-month regiments raised in the summer of 1862 that composed a significant percentage of the Army of the Potomac at Antietam. Students especially like William McKinley’s monument, not far from Burnside Bridge, where I discuss how memorial landscapes develop. Erected two years after the president’s assassination, it features a bas-relief bronze sculpture showing Sergeant McKinley serving coffee to men of the 23rd Ohio Infantry. The monument’s inscription informs observers that the martyred president had come “under fire” on September 17 and acted “personally and without orders.”

One last theme I develop is how the war affected civilians who faced catastrophic loss of property, helped care for thousands of wounded men, and cleaned up untold wreckage. I emphasize that civilians in the vicinity of Sharpsburg were among the very few residents of the Union who experienced the war so directly. Few Confederates, white or black, could claim as much.

I thoroughly enjoy visiting Civil War battlefields with my students. I have seen hundreds of them benefit from walking historic fields and woods, and I believe it is our obligation to make certain that future generations will have this same opportunity. ✯