Often overlooked among surviving Civil War accounts are the records of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.). The largest of all Civil War veterans organizations, from 1866 to 1956 the Grand Army of the Republic counted hundreds of thousands of Union Army veterans among its ranks in more than 10,000 local posts. While voluminous recordkeepers, the G.A.R. did not adhere to a firm policy for records retention upon the closure of a local post. As a result, local post records have become scattered or lost entirely.

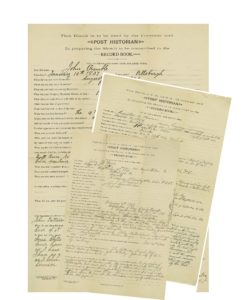

Among the most fascinating of G.A.R. records are Personal War Sketches. Surfacing just before the turn of the century, these sketches were compiled from pre-printed questionnaires or through oral histories conducted with the local Post Historian, who would then transcribe the dictations into a bound register. These questionnaires would pose veterans with more than two dozen pointed questions relating to their service during the Civil War.

Researchers can use any number of resources to verify much of the information these veterans provided. Dates of service, rank, organizations, hospital stays—these can all be checked against service records, many of which have been recently digitized.

Most intriguing, though, these Personal War Sketches touch on subjects that don’t always convey on standardized government forms. At the end of each questionnaire or interview, the veterans were asked to name their most intimate comrades during their service; what each veteran deemed his most important contribution to the war; and if there were any specific events they would like to ‘concisely’ record for posterity. Their answers offer a glimpse into the feelings and memory of these veterans several decades removed from their wartime service. Because their answers were not intended for publication or even to be shared outside the post, the veterans are seemingly candid or frank in their responses.

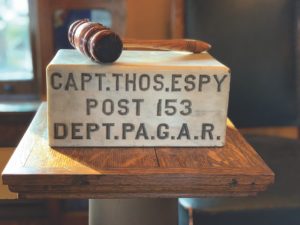

The Captain Thomas Espy Post in Carnegie, Pa., was chartered in 1879 and grew to include more than 200 members, ranging from lawyers and engineers to coal miners and laborers. Veterans of the Espy Post served in organizations from 13 states and included infantry, cavalry, artillery, and navy in both the Eastern and Western theaters. As such, the Espy Post serves as a good litmus test for the composition of average G.A.R. posts across the country.

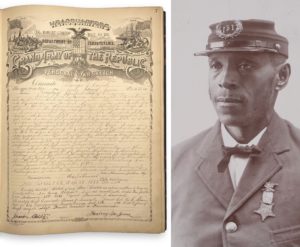

Located only several miles away from the Espy Post was the Colonel Robert G. Shaw Post, catering exclusively to African American veterans of the Civil War. Founded in 1881, the Shaw Post met for many years in the thriving African American community of Pittsburgh’s Hill District, and would boast more than 275 members, including 13 veterans who had served under Shaw in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. Like their Espy Post comrades, veterans of the Shaw Post represented a wide variety of regimental organizations.

Despite commonalities in geography and their service to the Union, members of the two posts did have divergent experiences. Many of the Shaw Post veterans were themselves born into slavery across the Southern states. Patriotic motives aside, these veterans were fighting for far more personal reasons. Unlike their White counterparts who faced death on the battlefield, in prison, camp, or the hospital, African American soldiers, if captured, faced re-enslavement or execution.

As such, veterans of the Shaw Post were justly proud of their service. At an 1891 meeting of the post, an ornate register for the recording of Personal War Sketches was donated as “a valuable and esteemed testimonial of…true loyalty and patriotism and esteem for the past service of those who dared death for the preservation of this great country.” The post recognized the importance of recording their wartime experiences, and that on the passing of the last veteran, “our children and our children’s children read with interest these lines and cherish the memory of those comrades…when the great cause for which they suffered and died will be known.”

Although the Espy Post did not have a dedicated register for its Personal War Sketches, dozens of the printed questionnaires survive, penned by the individual veterans. In comparing these Personal War Sketches from two seemingly disparate G.A.R. posts, several common themes emerge.

Comradeship was valued by veterans of both posts. Thomas J. Laurel was a veteran of the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry, the only African American cavalry regiment raised in Massachusetts during the war. Laurel’s service with the regiment would stretch from Petersburg, Va., to far-off Clarksville, Texas. Laurel remarked that “I was as loth [sic] to part from my comrades at discharge as I was to leave home when I enlisted.” One of Laurel’s comrades in the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry, Matthew Lucas, similarly said, “I was glad the war was over and that I could go home…I was loath to part from my comrades,” demonstrating the bonds that formed with these men who had together experienced battlefields and suffering.

In October 1864, William Strother enlisted as a substitute in the 32nd USCT, and within weeks found himself in line of battle at Honey Hill, S.C. Strother would survive numerous other engagements during the winter and spring of 1865, drawing him “very much attached to…the comrades of my regiment & company.”

Augustus Baum related that his most intimate comrade was “my own brother, Charles, who died from the effects of the hardships encountered in the service.” Augustus and Charles Baum had enlisted together in the 83rd Pennsylvania in February 1865. Charles died of disease only four months later at Arlington Heights, Va.

Baum’s sketch is notable, as well, for his recollection of a distressing incident during his first enlistment with the 37th Ohio during the winter of 1862.

“What do you deem the most important events in your service?” the sketch asks, to which he responds:

Could hardly tell. One was when wading across the icy Loup Creek, W.Va. waste deep about 20 times in a terrible dark wintry night under command of Gen’l Rosecrans and then stand picket with the wet icy cloth on till daylight, without being allowed to make the least light or fire, besides being treated at same time with 3 days starvation. The skirmishes and battles after were insignificant compared with the exposure mentioned. To state narrow escapes or other important events experienced sounds to egotistical and does not agree with my sense of good taste, no matter how intense my wish may be to comply with what is desired by the Post.

James McGrogan of the 62nd Pennsylvania also described a harrowing experience, his at the Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1, 1862. Severely wounded in the left leg, he was left on the field and captured by Confederate troops, who removed him to a nearby field hospital, where his leg was amputated.

The first Battle I think was at Orange Court house Va but soon came the memorial [memorable?] 7 Days in which we were all engaged until I was left on the feild at Malvernd hill[.] We sayed there for 15 days never got a cup of tea or coffee or any thing to eat except dough and the maggots running all over us. I could not describe the horrors we sufferd for the 15 Days. hoping I shall never experience the same again.

William Snyder of the 193rd Pennsylvania recalled his most memorable event:

Going from Camp Copeland to Baltimore I was standing on top of [train] cars and was struck on the head while passing under a Bridge at York Pa and suffer to this day from the Blow I received at the time.

Other veterans also recall broken health from their service that continued to plague them in their later years. David Hartzell of the 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry related that “my physical health has been greatly broken down from a complication of diseases contracted while in the services of the United States,” including kidney problems, chronic diarrhea, rheumatism, catarrh of the stomach, and general debility. John Trimble, a veteran of the hard fighting 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry, boasted of having had “as good health…as any man in the service,” but contracted “ague, chills and fever near Petersburg VA in summer of 1864 and have never been able to get clear from the effects. And I have it yearly yet.”

Most evocative among the Personal War Sketches for the Espy and Shaw posts are the accounts of those soldiers who spent time as prisoners of war. John Chaplin of the 3rd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery served as a guard over General W.H.F. ‘Rooney’ Lee at Fort Monroe following Lee’s capture at Brandy Station, Va. Lee was later exchanged, and Chaplin was himself wounded and captured at the Battle of Cold Harbor.

Was a guard over Genl Lee (Jr) in Fortress Monroe Va. and prevented him from escaping there. When I was captured I was taken to his tent and he recognized me, but gave me good treatment and my wound was treated better after seeing Gen Lee.

Mathew Nesbit, a former slave, served briefly as a servant in the 8th Iowa Cavalry before enlisting in Company E, 44th U.S. Colored Troops. At Dalton, Ga., on October 13, 1864, Nesbit and more than 700 of his comrades were captured in what would be the single largest surrender of African American troops during the Civil War. Though wounded from a clubbed musket, Nesbit was determined to avoid a fate outlined nearly two years before by Confederate President Jefferson Davis—that he and his comrades be returned to a state of slavery, or even face execution. In his sketch he reveals his story:

Mathew Nesbit first inlisted the 14th day of June 1864 at Chattanooga Tenn as Private in Company E 44 regiment of collar volleters for a period of 3 year and as following in Tennsee, Georgia, Misspia, Alabama. On ore about September 1864 was taken prisner of war at Dalton Georga and was wonde in the sholders with the stroke of a mustket and brok prison near Carent Miss and was recaptured near sumervill Alabama. Brok prison near Gunters Vill Allabama on the march from Chattanooga Tenn July 1864. Was sick from the mesals but marched the hol way without medson or atenton to Rome Georga. The mesals went in on me deurn time of my imprison. I suffer with the afect. About Ap 1864 I went in the 8th Iowa Calvry Company H. That was captin Mat Woldon’s Co and at the Batel Actworthe the, the Batel of Big Shan all times at first of Batt of Kennesaw Mouten. This was befor I inlisted in the 44 Reg of infray.

I was a slave and was ond by William Nesbit of Gorden County Georga. At the clos of the war I was muster out of sirvis at Nashville Tenn in Apr 30 1866.

Another Shaw Post veteran, Edward Logan of the 55th Massachusetts, relates being captured with two of his comrades at North Edisto, S.C. in November 1863. Logan “thought that we was done for sure, as Jefferson, the Confederate President, had issued orders to hang all of the n___r soldiers that was captured fighting with the Yankees.” Instead, Logan and his comrades were sent to a series of prison camps, and after 15 months Logan was the only one of the three to survive the ordeal. “I don’t know how I did live to come out,” he marveled, confessing, “I was no good as a soldier afterwards.” In closing, he shared a sentiment likely felt by many prisoners of war, “I did not see much of the war, but I was in a much worse place than the battlefield.”

Charles McDonald, a veteran of Battery I, 2nd Illinois Light Artillery, was captured by soldiers of the 45th Alabama at Big Shanty, Ga., on June 7, 1864, and would eventually be sent to five different prison camps. An incident at Camp Sorghum in Columbia, S.C., stuck with him in particular. On October 13, 1864, Lieutenant Edward B. Parker of Battery B, 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery, died of injuries received from bloodhounds while trying to escape from the prison. In his Personal War Sketch, McDonald wrote about an equally grisly incident in December 1864 related to Parker’s death:

From February 14th 1865 I was held prisoner at Charlotte N.C. a few days from thence to Raliegh N.C. from there to Goldsboro N.C. where on March 11th taken for exchange or rather parole. In connection with my prison life there is one incident which occured Dec 8th 1864 at Camp Sorghum Columbia that was dangerous and exciting. I with my own hand killed two blood hounds that was kept there for the especial purpose of running down and tearing to death prisoners who escaped. The death of one Lieut Parker being most beastly and inhumane I was anxious to avange which I did.

Four days later, McDonald was transferred from Camp Sorghum and was released from confinement in March 1865.

Many veterans expressed a sense of patriotism and satisfaction in having served their country. William Chambers, who spent two years with the 88th Ohio guarding Confederate prisoners at Camp Chase, said he enlisted “to save our country.” Reese Evans of the 110th Pennsylvania was proud that “I offered my services to my country.” Isham Lafayette of the 2nd USCT

Cavalry deemed “the most important events of my service was to be always able and willing to do my duty.”

At least one veteran, Daniel H. Rice of the 102nd Pennsylvania, remained defiant after the passage of several decades. While Rice’s service records indicate he was drafted and mustered into service in July 1863, Rice claims in his Personal War Sketch that he had actually entered the service with the regiment in March 1862. He claims that while on the way to meet the regiment, he and 25 men were attacked by a party of guerrillas, during which the officer in charge lost his satchel, containing the correct enlistment papers. As such Rice asserts that his descriptive records were incorrect because “they filed up papers in Washington to suit themselves to hold us in the army.”

Finally, even several decades removed from the conflict, many of the veterans were simply thankful to have survived. Espy veteran John Trimble remarked with pride, “I was in it and lived to see the end of it, and the glory now of being one that helped to end a rebellion.” George D. Grouse, a veteran of the 8th USCT who suffered a painful leg wound at the Battle of Olustee, Fla., in February 1864, noted that “the most interesting event of my soldier life was that I was not killed in some of the battles that I was engaged in.” Enoch Holland of the 9th Pennsylvania Reserves recalled his most important event during his service was “being shot at and trying to keep from being hit,” while Captain William J. Glenn of the 61st Pennsylvania, wounded at Charlestown, W.Va., in August 1864, noted that “I simply, reverently, thank God that I am a survivor.”

A simple Google search finds that several libraries and archives have digitized various Personal War Sketches from their collections, including the sketches of the Espy Post veterans, available at www.carnegiecarnegie.org. The Personal War Sketches of the Shaw Post are part of a collection of more than 2,000 sketches held at Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Hall in Pittsburgh. These accounts offer a terrific resource for evaluating the experiences and memory of the common soldier in his own words.

Jon-Erik Gilot is a contributing historian at Emerging Civil War. He works as an archivist and public historian in Wheeling, W.Va., and since early 2021 has served as Curator at the Captain Thomas Espy Grand Army of the Republic Post in Carnegie, Pa.