A daring reporter tells Abraham Lincoln what his own government would not

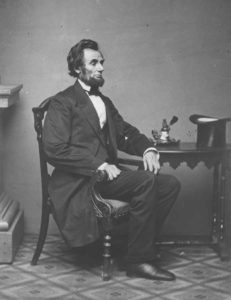

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]braham Lincoln paced nervously in the telegraph room on the second floor of the War Department building next door to the White House. He was waiting for news—as he so often did there—from the latest battle, raging 50 miles to the south at Fredericksburg, Va.

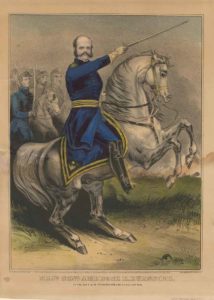

It was December 12, 1862, the day his latest choice to command the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, was supposed to attack General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Fredericksburg. Every general that Lincoln had chosen to lead his main army thus far had been a disappointment. Battles had been lost with appalling casualties, and hopes for a quick victory were fading. Would this battle finally turn the tide of war and lead to the defeat of Lee and the Southern rebellion? Lincoln was desperate to know.

The initial news was encouraging. On December 11, Burnside’s forces had crossed the Rappahannock River to the Confederate side. As historian George C. Rable would write in Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!, the hopeful telegrams arriving in Washington reported “the successful crossing of the Rappahannock and the troops cheering Burnside….[There was] even a wire from General [Edwin V. “Bull”] Sumner to his wife—‘Fredericksburg is ours. All well.’” Thus, what Lincoln had read to that point had given him reason to hope that, as he put it, the “rebellion is now virtually at an end.”

The president nevertheless remained concerned. He didn’t know it, but the battle had not gone as planned. Only sporadic fighting occurred on December 12. The next day, Burnside launched his attack across a wide front, including on the Confederates’ well-defended positions on a range of hills, Marye’s Heights, just beyond the town. When the battle finally ended at sundown, Burnside’s army had suffered a staggering defeat, with nearly 13,000 troops killed, captured, or wounded. The fields of grass across the expansive battlefield were stained red with the blood of Union soldiers.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The public was cut off from all access to information. And so was Lincoln.[/quote]

British correspondent Francis Lawley would later write in The [London] Times that the Union dead were “lying so close to each other that you might step from body to body…nothing like it has ever been seen before.” No one in command at the scene, or at the War Department in Washington, wanted the American people to know the terrible magnitude of the defeat.

While Lincoln waited for word, Northern newspapers, in the absence of any real news, simply reported that a decisive battle was raging. The morning of December 14, The New York Times noted, “At this writing, no results are known.”

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles was among those increasingly suspicious about the absence of definitive reports from the field. He wrote in his diary that the War Department was afraid “to admit disastrous results….When I get nothing clear and explicit at the War Department, I have my apprehensions….[A]dverse tidings are suppressed with a deal of fuss and mystery.”

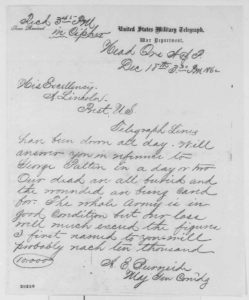

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton knew no more than anyone else in Washington. After receiving only vague accounts hinting at success, he ordered that no one in the capital be permitted to send telegrams describing anything about the battle.

At the front in Fredericksburg, Burnside added to the censorship by issuing an order forbidding anyone, especially reporters, from dispatching telegrams or boarding the boats that regularly traveled the Potomac between Washington and Aquia Creek, 12 miles north of the battlefield—the quickest and most direct way of reaching the capital. Thus, the public was cut off from all access to information. And so was Lincoln.

Burnside had not, however, counted on the determination of Henry Villard, a 27-year-old reporter for the New York Tribune, who had witnessed the Union defeat. Villard wanted to be the first to tell the story of the debacle, to scoop all the other reporters who had been there, too. But to do that, he would have to get to Washington before anyone else.

Villard, who had emigrated from Germany to the United States only nine years before—having at the time no money to his name and unable to speak a word of English—slipped out of Fredericksburg on horseback at 3 a.m. on December 14. He was headed for Aquia Creek, a ride that usually took three hours, to catch the boat to Washington. It had been raining heavily and the road was thick with mud. His horse stumbled several times along the way, once throwing him to the ground. He was not injured, but the fall left him covered in mud.

After six exhausting hours, he reached the boat landing, only to be told by the officer in charge that Burnside had ordered no one was to proceed by water or land to the capital. Determined not to be thwarted, Villard strolled casually along the riverbank until he spied two local fishermen in a rowboat. Making sure no soldiers were watching, he offered the men $6 each [a Union soldier’s wage was then $13 a month] if they would row him out into the middle of the river where the government steamboats passed back and forth between Fort Monroe at Hampton, Va., and Washington.

Villard was aware those boats did not stop at the Aquia Creek wharf and would not be restricted by Burnside’s orders. If he could somehow wangle his way aboard, he might be able to reach the capital. The captain of the first steamship that came by refused him permission to board, claiming that a cargo vessel could not legally take on passengers.

The resourceful Villard grabbed a rope that was dangling over the side and told the two men in the rowboat to head for shore as quickly as they could. Villard hauled himself up on deck, leaving the captain with no choice but to let him stay. He wasn’t about to simply toss him back into the river.

“The captain was at first disposed to be wrathy at my summary proceeding,” Villard later wrote, “but became mollified on being shown my general army pass, and on my assurance that I commanded enough influence to protect him in case my performance should get him into trouble.” Villard also promised the captain a cash payment of $50 to let him stay on board.

When the steamer arrived in Washington that afternoon, Villard rushed to the F Street offices of the New York Tribune to send his report, but found that Stanton had forbidden that telegrams dealing with the battle be sent: No mention of the terrible Union loss was to get out of the capital.

Villard handed his written copy to a courier, who promised to take the night train to New York to deliver the article to his editor, Horace Greeley, in time to be printed in the December 15 edition. Confident that he had scooped every other reporter who had witnessed the carnage at Fredericksburg, Villard went for dinner at the fashionable Willard Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue, a six-minute walk from the White House.

During the meal, Henry Wilson, a well-connected Massachusetts Republican senator who knew that Villard had been at Fredericksburg, came to his table. “What is the news?” he asked. “Have we won the fight?”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]No mention of the terrible Union loss at Fredericksburg was to get out of the capital[/quote]

Villard told him plainly and clearly that it had been yet another staggering defeat for the Union, leaving a large number of casualties. The Army of the Potomac was in disarray and in danger of being overrun if Lee decided to counterattack. Villard urged the senator to tell the president immediately how serious the situation was.

After Wilson left, Villard finished his dinner and returned to his office to prepare his expense account. But at 10 p.m., the senator rushed in, announcing that Lincoln wanted to see him right away. As they both walked over to the White House, Wilson informed Villard that he had not told Lincoln everything—it would be Villard’s job to give the president the bad news.

Villard, who had known the president since 1858 and, as a reporter, often interviewed him, recounted the action at Fredericksburg, saying that in his view it was the worst defeat the Union Army had ever suffered. Lincoln, looking increasingly upset, asked several detailed questions. Villard recommended that Lincoln order Burnside to withdraw across the Rappahannock and not to try again to attack Lee’s well-defended positions on the south side. Lincoln smiled sadly, thanked Villard for coming, and said, “I hope it is not as bad as all that, Henry.”

About midnight, an hour or so after Villard left, another White House visitor confirmed his account. Andrew G. Curtin, the powerful governor of Pennsylvania, whom no one, not even a high-ranking military officer, would try to stop from going anywhere, had come directly from the battlefield. Curtin described what he had witnessed, corroborating Villard’s description.

“Mr. President,” Curtin said bluntly, “it was not a battle, it was butchery.”

An aide to the president described him as crestfallen and in despair. “If there is a worse place than Hell,” Lincoln would say, “I am in it.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]“If there is a worse place than hell, I am in it.” -Abraham Lincoln[/quote]

Villard went back to his office to complete work on his expense account. Just as he entered the final figures, his boss, Sim Wilkeson, the Tribune’s Washington bureau chief, interrupted him. Wilkeson had obviously had more than a few drinks too many at Willard’s bar. When he saw Villard’s expense sheet, he exploded in anger.

“Twelve dollars to two Negroes for a ride in a rowboat! Fifty dollars to the captain of a cargo vessel for a trip up the river!”

He accused Villard of falsifying his expenses. In his rage and drunkenness, he shoved Villard backward. According to Villard’s biographers, “Wearily and methodically, Villard knocked his opponent down, let him get up, and knocked him down again. After repeating this a few times, Villard decided to call it a day, [he] knocked off, as it were, and went back to his rooms.”

Although Villard was exhausted by the day’s events, he was pleased with what he had accomplished and eager to see his byline on the article he expected to see in the December 15 newspaper, exposing the full extent of the defeat at Fredericksburg, relishing his scoop about the true story of what had happened there.

But it was not to be. When Villard’s editor, Greeley, read the piece, he decided it would be too shocking, even demoralizing for the general public, and too different from the official government version of events. He rewrote the article and published it under Villard’s name, even though it no longer represented what Villard had reported. It was fake; no longer the real news.

Margaret Leech, a Pulitzer Prize–winning historian, wrote in 1941, as America was about to enter a new war, that “Villard’s beat [scoop] was wasted—a fate which frequently overtook early reports of bad news during the war.”

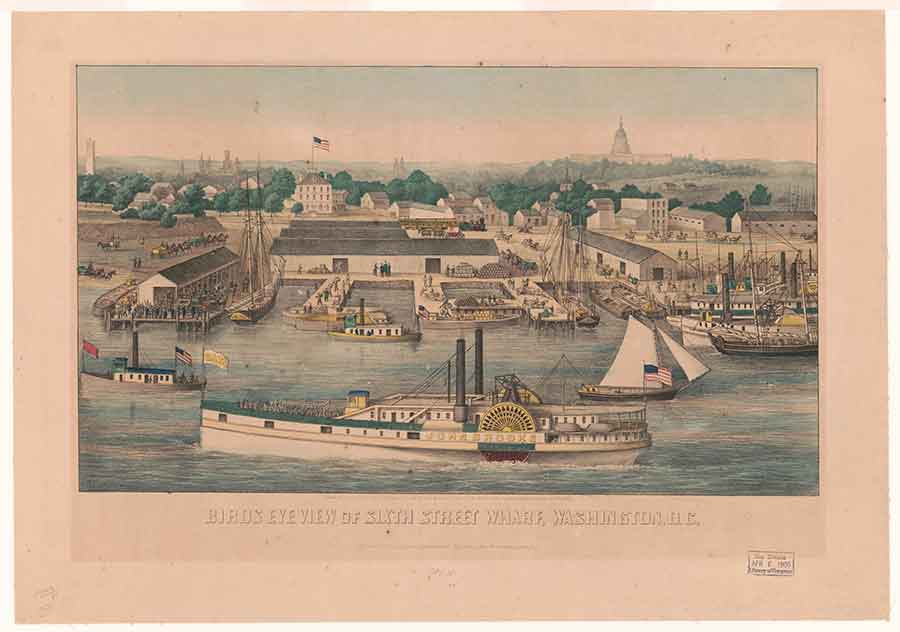

It was not until the following day that the truth of the disaster at Fredericksburg was reported correctly throughout the Union. The people of Washington saw and smelled the ugly truth themselves, even before reading about it, when a large fleet of boats arrived from Aquia Creek.

“At the wharves,” Leech wrote, “the stir of trade ceased, as out of the Potomac mist moved the white and silent transports. Thousand after thousand, men littered the landings, like spoiled freight.” At the seedy Union Hotel, now one of 56 makeshift hospitals, the writer Louisa May Alcott, then serving the war effort as a nurse, was awakened by a pounding on the front door. According to Margaret Leech, Alcott “saw forty wagons like market carts lining the dusky street.” The wounded and mutilated soldiers who were carried into the hotel all wore “that disheartened look which proclaimed defeat, more plainly than any telegram of the Burnside blunder.” And this was only a fraction of the thousands of dying men who overwhelmed the capital city in the days to come. Not even the War Department could hide the truth any longer.

After the war Henry Villard, ever the hard-working and ambitious immigrant, became a multimillionaire, president of the Northern Pacific Railway and the Edison General Electric Company. He made generous financial contributions to both Harvard and Columbia universities and to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History. He married Helen Frances “Fanny” Garrison, a leader of the women’s suffrage movement and the daughter of noted abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. Villard’s experiences during the Civil War reportedly made him a confirmed pacifist. He died on November 12, 1900.

Duane Schultz has written numerous articles and books on military history, including The Dahlgren Affair: Terror and Conspiracy in the Civil War and The Fate of War: Fredericksburg, 1862.