Confederate officers’ wounded pride leads to fury, insults, and senseless murder

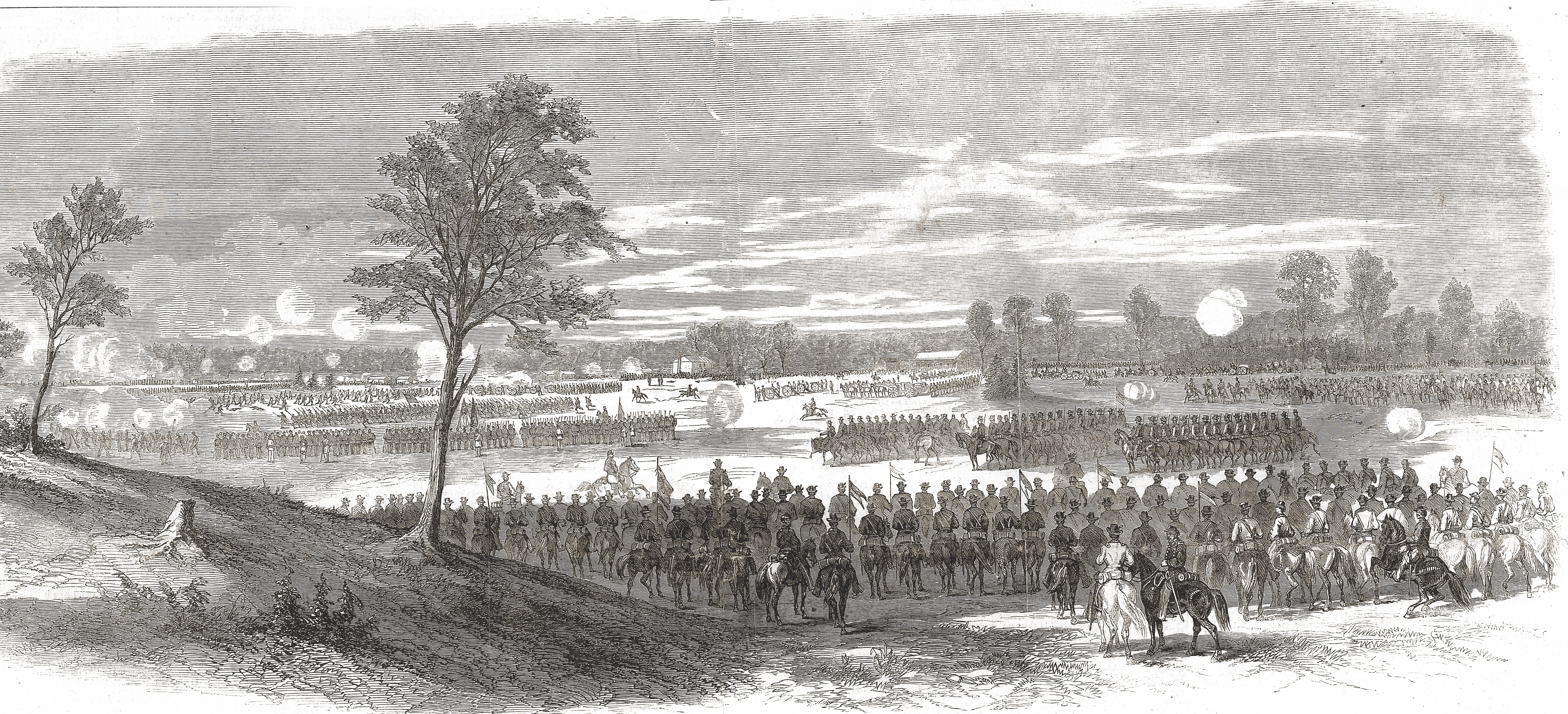

On April 6, 1865, the Confederacy was in its death throes. Robert E. Lee’s defeat at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek, Va., had all but ended the fighting in the Eastern Theater. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Rebels were doing all they could to hold back James Wilson’s cavalry in northern Alabama, and in North Carolina, William T. Sherman continued to close in on Joe Johnston’s depleted army. Meanwhile, far away from the battlefield, two high-ranking Confederate officers in Texas were waging their own private war.

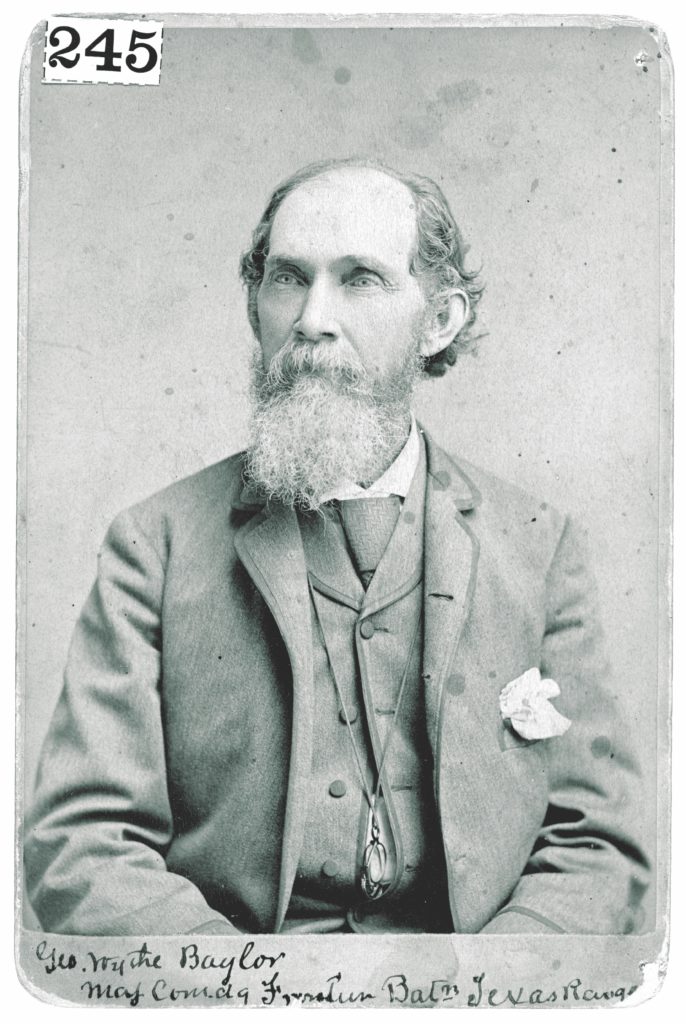

Colonel George Wythe Baylor and Maj. Gen. John A. Wharton did not start out as enemies. After all, they were both Texans, fighting under the same banner and fiercely devoted to the Southern cause. Baylor, in fact, reportedly had raised the first Confederate flag in Austin during the Lone Star State’s secession debates in 1861. Both men had distinguished themselves on multiple battlefields and should have been brothers in arms. But they also came from very different backgrounds—one to the manor born, the other having to fight for everything he ever got.

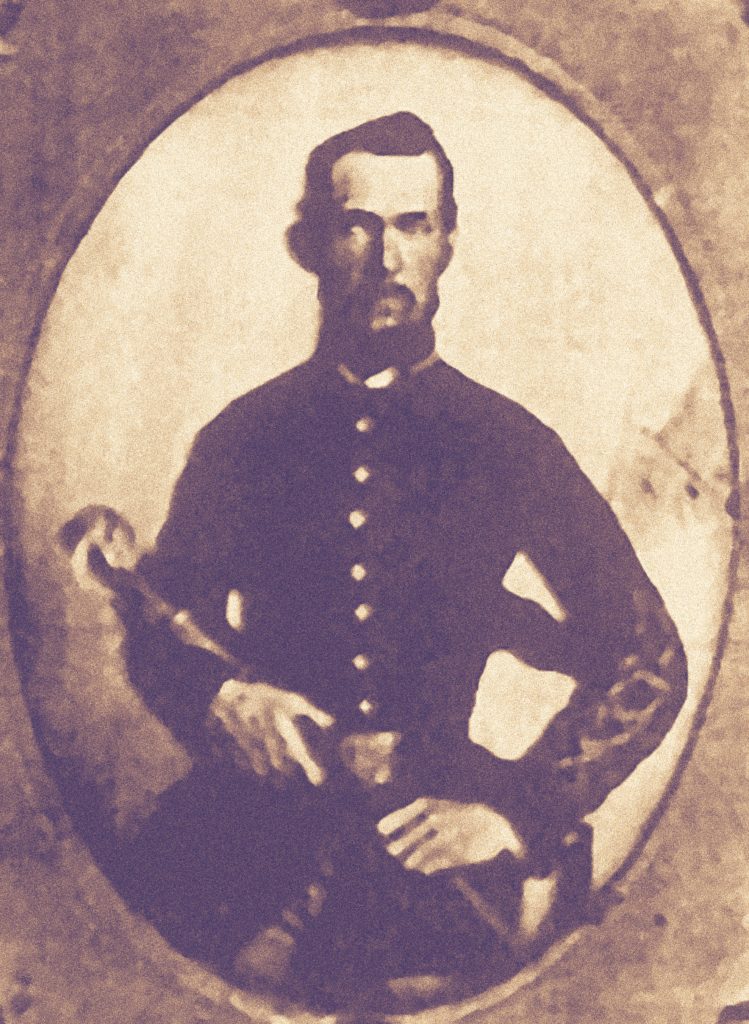

Baylor was from simple stock, but rose through the Confederate ranks through brains, courage, and pure ability. He served on General Albert Sidney Johnston’s staff until Johnston was mortally wounded at Shiloh on April 6, 1862, and won commendations for gallantry while commanding a regiment during the April 8-9, 1864, fighting at Mansfield and Pleasant Hill in Louisiana. The brother of Colonel John Baylor (see “No Mere Sideshow”), he undeniably had the heart of a lion but was also a bantam rooster of a man. After four years of fighting, he was in “exceedingly delicate health,” suffering from chronic dysentery that had reduced him to a gaunt 135 pounds.

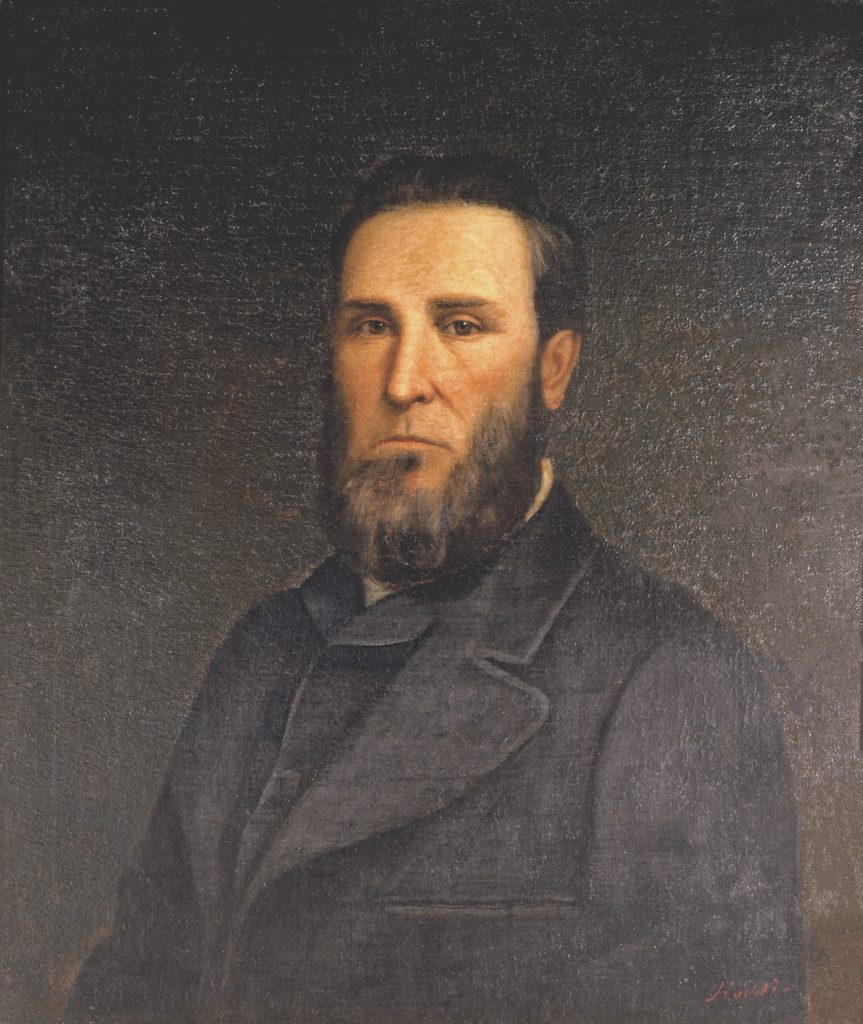

John Wharton, on the other hand, hailed from a privileged family, which allowed him to attend South Carolina College and marry the South Carolina governor’s daughter. Wharton took up law and was serving as district attorney of Brazoria County, Texas, in February 1861 when he attended the Secession Convention as a delegate. He voted in favor of Texas leaving the union, and when war followed, he raised a company of cavalry that was mustered into Confederate service with Benjamin Franklin Terry’s 8th Texas Cavalry.

When Terry was killed at the Battle of Rowlett’s Station, Ky., in December 1861, Wharton took command of Terry’s renowned Texas Rangers. His performance at Shiloh in April 1862 brought him a promotion to brigadier general and a request from friends back home to run for a seat in the Confederate Congress. His mother turned down the offer for him, however, insisting that her son would rather fight than legislate. Wharton remained in the cavalry, fighting under both Forrest and Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler over the next two years. He was promoted to major general after the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863, and fought capably during the Red River Campaign the following spring.

By 1865, he was part of Maj. Gen. John Bankhead Magruder’s crumbling Trans-Mississippi Department. When Magruder reorganized the department in late 1864, he placed Baylor’s regiment under Wharton’s command. Wharton had a reputation for taking care of friends and family first—and George Baylor was neither. So, when dismounted troopers were needed to form an infantry division, Wharton tapped Baylor’s men, much to the colonel’s chagrin. This put Baylor and his troops under the doddering, 66-year-old Colonel Nathaniel Terry, whose rank dated back to the days of the Republic of Texas and whose Civil War commission had been bestowed by Governor Pendleton Murrah.

Although Terry had no combat experience during the Civil War, and his appointment in state forces made his rank inferior to Baylor’s rank in the Provisional Army, CSA, Wharton and his staff believed that wouldn’t be a problem: Because Terry would not be able to take the field, it made Baylor the brigade’s effective commander. That, however, mattered little to Baylor, who was driven by the principle of the matter.

Wharton’s personality did not help the situation. He had a deserved reputation of being “exceedingly dictatorial” in his relations with subordinates and swore without regard for the rank or position of those to whom he was speaking. Those who knew him best said he was “in the habit of accompanying every sentence with a ‘damn.’”

While they served in the same army and the same theater, Wharton and Baylor scarcely knew each other. But on April 6, both were in Houston. Baylor continued to seethe at having to serve under Nathaniel Terry. He took it as a personal insult and wanted his command reassigned anywhere but with Terry, and he was willing to voice that desire to anyone who would listen. That morning he buttonholed Brig. Gen. Walter P. Lane at the railroad depot, hoping to get Wharton’s orders countermanded. Lane refused to intervene. Afterward, as Baylor and Captain R.H.E. Sorrel (or Sorrelle) were walking through town, they spied Wharton and Brig. Gen. James E. Harrison in a buggy. The pair had come in from Wharton’s camp at Hempstead, 50 miles northwest of Houston. Wharton confronted Baylor, upbraiding him for not being with his command. Baylor replied that his services were “needed here” to keep his unhappy men from deserting rather than serve under Colonel Terry. “I have been imposed upon by you, Gen. Wharton, and I am determined to see Gen. Magruder about the matter.”

As Baylor kept talking, his voice rose: “This thing has been going on for some time, and I don’t think that my right has been awarded to me….The only time that I ever asked a favor of you was when my wife was sick, and I asked an extension of leave….” The implications were clear: Baylor was asking to be reassigned now as another favor.

Responded Wharton: “Who has done you injustice?”

“You, sir,” Baylor shot back; “You have always borne upon me,” and he ticked off several instances as evidence.

Both men had their dander up now. After hearing Baylor out, Wharton called him a “damned liar,” to which Baylor fired back: “You’re a demagogue! You rank me now, but the day is coming when we will be on equal grounds.”

Wharton snorted, dismissing Baylor’s accusations as “false or a lie.”

Repeated Baylor, “You are a liar and a demagogue,” and he stepped forward with raised hand as if to strike Wharton. Before he could do anything, however, an alarmed Harrison urged the horse forward.

“Stop the buggy, sir!” Wharton cried, informing Baylor he was under arrest and ordering the colonel to report to his Hempstead headquarters immediately—by the next train.

Replied Baylor: “General, I will go to see Gen. Magruder before I leave to have justice done me.” Wharton and Harrison then drove off, ending the immediate confrontation, but neither man was satisfied with how things had ended. Raw feelings like these could be assuaged only by a public apology, yet neither man was about to do that.

Baylor and Sorrel went directly to Magruder’s headquarters on the second floor of Fannin House. Informed the general was not there, Baylor told Magruder’s adjutant, Colonel Edward P. Turner, “I have been called a liar and placed under arrest.” He then stalked out of the room to go find the department commander.

After stewing over the morning’s events, Wharton, still accompanied by Harrison, also headed to Fannin House to see Magruder and “settle things.” Upon entering the hotel, Wharton inquired whether Baylor was upstairs. When the answer came back in the affirmative, he proceeded up the stairs. Wharton and Harrison went to Magruder’s private rooms and entered. Magruder was not there, but Baylor was, sitting on the side of the bed.

Wharton, a cigar clenched in his teeth, advanced, roaring, “Colonel Baylor, you have insulted me most grossly this morning.” Harrison tried to interpose himself between the two angry men, but it was too late. Wharton, who wasn’t armed, struck Baylor in the face with a clenched fist. Outraged, Baylor responded with a roar of his own, drawing his Navy revolver and pointing it at Wharton. Again, Harrison desperately tried to get between the two men, but Baylor fired under Harrison’s arm at point-blank range, striking Wharton in the heart and killing him instantly.

Baylor then simply walked out of Fannin House and surrendered to military authorities. Contrary to some reports, Magruder wasn’t in the building at the time and probably couldn’t have stopped the confrontation even if he had been. Subsequently, Baylor was returned to duty. He never attempted to flee, seeing no need to since he felt entirely justified.

Ordinarily an episode such as this would be filed under “affairs of honor” between gentlemen—in other words, a duel—except that none of the ritualized rules of dueling had been observed. This had been an execution of an unarmed man. Charges should have been filed, but Confederate authorities, understandably, were preoccupied with the war. Justice would have to wait.

Wharton’s body was transported to Austin for burial, with full military honors. Magruder himself led the procession through Houston to the train depot. When the war ended, George Baylor went back to civilian life.

The legal repercussions of the shooting did not play out for another three years. The delay can be explained in part due to the unabated turmoil across the South at the end of the war and the beginning of Reconstruction. But there was also a question of jurisdiction. This was a case of one officer killing another, which should have been tried under the military justice system. But the Confederate States no longer existed. If there was to be justice, it would have to be in a civil court. Thus, the case of State of Texas v. George W. Baylor opened in Houston’s Harris County District Court on May 16, 1868—Judge C.B. Sabine presiding. Previously, the details of the case have never come out, and most of what has been written in the history books is incorrect because accounts of the affair depended on sketchy newspaper reports of 1865 rather than testimony under oath. No one, apparently, thought to look for the story three years after the event. Fortunately, the trial proceedings have recently come to light, so we have the testimony of witnesses taken under oath.

When both sides took their place, the courtroom looked like a soldiers’ reunion of the old Confederate Army, with men still wearing their uniforms and using their wartime military titles. For the prosecution were “General” D.A. “Jack” Harris, whose rank as given is suspect because no such general appears in any listing of Confederate or state officers; Colonel Hiram B. Waller, who was better known as a criminal prosecutor after the war than a Confederate veteran; and Captain T.W. Masterson, who had been an assistant adjutant general on Wharton’s staff.

The defense was led by George Mason, Esq., a Galveston County justice of the peace who went on to defend KKK defendants against federal prosecution a couple of years later; Judge George Goldthwaite, Esq., a district court judge in Austin at the time of the trial who may or may not have served in the Confederate Army during the war; and James Wilson Henderson, Esq., interim governor of Texas (1853) who was serving as a captain under General Magruder at the end of the war. What all these men had in common, on both sides of the case, was they had all been true believers in the Confederacy and staunch Democrats who believed in the so-called “Lost Cause.” Tacking “Esquire” onto the end of their names in some ways helped assuage the pain of losing their rank when the Confederate Army was no more.

The prosecution presented its case first, calling as witnesses Colonel Waller, Isaac V. Jones, and General Harrison, all of whom went easy on the accused because he also happened to be a former comrade in arms. When it came their turn, the defense called Major Jared E. Grace, who had been assistant inspector general on Wharton’s staff; T.T. Hailey [or T.J. Haley]; Major Sorrel; John S. Sydnor, a former mayor of Galveston (1846-47) as well as a slave trader who rose to the rank of colonel in the Confederate Army before resigning to return to business; and Major Michael Looscan, who ultimately became the most distinguished veteran of them all as a member of the board of managers of the Texas Confederate Home (1892-97). “Lost Cause” loyalty ran deep, and these proud Southerners all testified to the defendant’s sterling character, kindly disposition, and military record.

It was established early that even before the fatal day there had been hard feelings between Baylor and Wharton. Isaac Jones testified that two weeks earlier he had been part of a dinner conversation in which an unnamed colonel whose troops had been reassigned by Wharton said he wanted to kill the general. When Baylor chimed, “Give me half a chance, and I’ll kill him myself,” Baylor’s wife reproved her husband: “Why George, you shouldn’t talk so.” The defense dismissed the statement as a “careless, idle remark calculated to injure no one.”

It was important to establish for the record whether Wharton had struck Baylor with his fist or merely slapped him. To most of those present, it didn’t matter, claiming that no Southern gentleman would meekly accept being physically assaulted. The prosecution sought to establish that Baylor was “not in any danger of any serious injury” at the time he shot Wharton, and that though Wharton was physically larger, he was neither “a strong nor athletic man.”

The defense stressed that both men had sworn at each other, also emphasizing that Wharton was much larger physically than Baylor. The defense also showed that it was customary for Confederate officers to be armed, clearly implying that Baylor had every right to expect that the man who had struck him was likewise armed and prepared to answer for his actions. In addition, the defense presented a seniority list of Confederate officers according to general orders issued by Magruder on February 21, 1863. The list clearly showed that Baylor was of superior rank to Nathaniel Terry.

All these facts weighed heavily in favor of the defendant when the jury retired to begin deliberating. They also must have been cognizant of the fact that the affair had occurred at the end of the war, at which time many Southerners were trying to get on with their lives. Finally, there was no denying that George Baylor was a living Confederate hero, and those could be forgiven almost anything.

During the testimony, several eye-opening revelations provided a peek inside the Confederate command structure as well as frontier justice in Texas. Several defense witnesses expressed surprise that Wharton had carried no weapon, insisting it was Southern custom, especially in the cavalry, for officers to go about armed at all times. Interestingly, the prosecution did not challenge that testimony.

Defense witnesses also testified that it was “against etiquette” for a superior officer to directly address a subordinate whom he had placed under arrest. The implication was obvious that Wharton had no business addressing Baylor after he placed him under arrest and ordered him to report to his headquarters. And during the same dinner conversation noted above, the gentlemen present discussed the “merits” of Nathaniel Terry and Wharton and had “nothing complimentary to say about either.” That underscores Terry’s lack of experience and raises questions about Wharton’s reputation in history.

On May 18, in closing arguments, the prosecution went first, with Waller arguing that it was well known that ex-Governor Henderson was “the best man in the state to stock a jury,” thus suggesting that if a verdict came back other than “guilty,” it was because the jury had been paid off. Henderson leaped up to protest, and Judge Sabine warned Waller to “cease such remarks.” Henderson and George Mason then followed, splitting the time for the defense’s closing argument. Both delivered “forcible and convincing” speeches, sprinkling their remarks with quotations from relevant legal authorities. Harris wrapped up the prosecution’s case, speaking until 9:15 p.m., when the case went to the jury.

he following afternoon, the jury reported it was unable to reach a decision and was therefore discharged, with Sabine continuing the case until the next court term. Posting $25,000 bail, Baylor remained free. The case returned to trial in December 1868 with the same legal teams in place. But a new question needed to be resolved: Had the original charge been murder or manslaughter? The judge decided murder and so instructed the jury, which needed only half an hour to deliver a “not guilty” verdict.

When it was over, Baylor had suffered no loss of reputation or diminution of status for his actions. On the contrary, he went on to live a very public life, becoming a distinguished Texas Ranger and being elected to several terms in state office before his death in 1916. The Houston Telegraph put the best possible spin on the case: “The high-souled Wharton lost his life at the hands of the noble-spirited Baylor. It was a public misfortune and a public grief.”

Dr. Richard Selcer, a frequent contributor to America’s Civil War, is a professor of history and author based in Fort Worth, Texas. This story appeared in the March 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.