When Chinese emperor Zhu Yuanzhang and his Ming Dynasty forces conquered Yunnan Province, the last remaining Mongol bastion, in 1382, they captured a 10-year-old Muslim boy whose father had been killed in the bloody fighting. The boy, Ma He, brazenly told the victorious General Fu Youde that the Mongol leader he was looking for had jumped into a pond. Impressed by the youth’s boldness, Fu placed him in the household of Prince Zhu Di, the emperor’s fourth son, who was Fu’s aide. As was typical for new imperial servants, Ma He was soon castrated. Over years of service, the young eunuch became a devoted follower of Zhu, a talented soldier in his own right and a future admiral in the Chinese navy.

Zhu Di, a competent leader like his father, was put in command of the empire’s northern region, with his headquarters in Beijing. He was charged with warding off the still aggressive Mongol forces along China’s northern frontier. Living in the prince’s household in Beijing, Ma He fought alongside his master on all his military campaigns, learning the art of war and earning his trust. He grew into an exceptionally large man, well over 6 feet tall, with glaring eyes and a powerful voice. Unusual for a lowly eunuch, he also received a good education.

After his oldest son, Crown Prince Zhu Biao, suddenly became ill and died, the aged emperor had to consider who would succeed him. His advisers counseled against selecting Zhu Di, his favorite surviving son, arguing that to do so would cause a rift among the other sons and plunge the country into civil war. Instead, he was advised to choose his 14-year-old grandson, Zhu Yunwen, the traditional next in line for the throne. Before the emperor died in 1398, he ordered his sons to remain in their fiefdoms and not attend his funeral to avoid any possible challenge to his grandson’s succession.

On ascending the throne, Emperor Zhu Yunwen stripped his uncles of their military forces and put them under house arrest. One of his uncles, Zhu Bo, was so angry that he burned himself and his family alive. By the summer of 1399, five of the most powerful princes had been eliminated or had died of natural causes. To forestall meeting a similar fate, Zhu Di pretended to be insane and tricked the emperor into allowing Zhu Di’s three sons to return home to take care of him.

When the emperor sent troops to arrest Zhu Di’s supporters, the prince ordered the imperial commanders killed and commenced open rebellion against the throne. After some early victories against the imperial army, the prince was trapped in Beijing for several months before breaking out of the siege in January 1402. He fought his way south to Nanjing and captured the capital, aided by the defection of the imperial commander and senior household eunuchs who were angered at the emperor’s draconian restrictions.

On July 13, Zhu Di marched triumphantly into the capital. But he found the imperial palace in flames. The wreckage contained the charred bodies of the empress and her eldest son. Another body, burned beyond recognition, was believed to be the emperor. After Zhu Di ascended the throne, he quickly ordered the execution of all the officials and military officers who refused to recognize him, along with their relatives and neighbors, teachers, servants, and friends. Despite this violent beginning, Zhu took the imperial name of Yongle, meaning “perpetual happiness.”

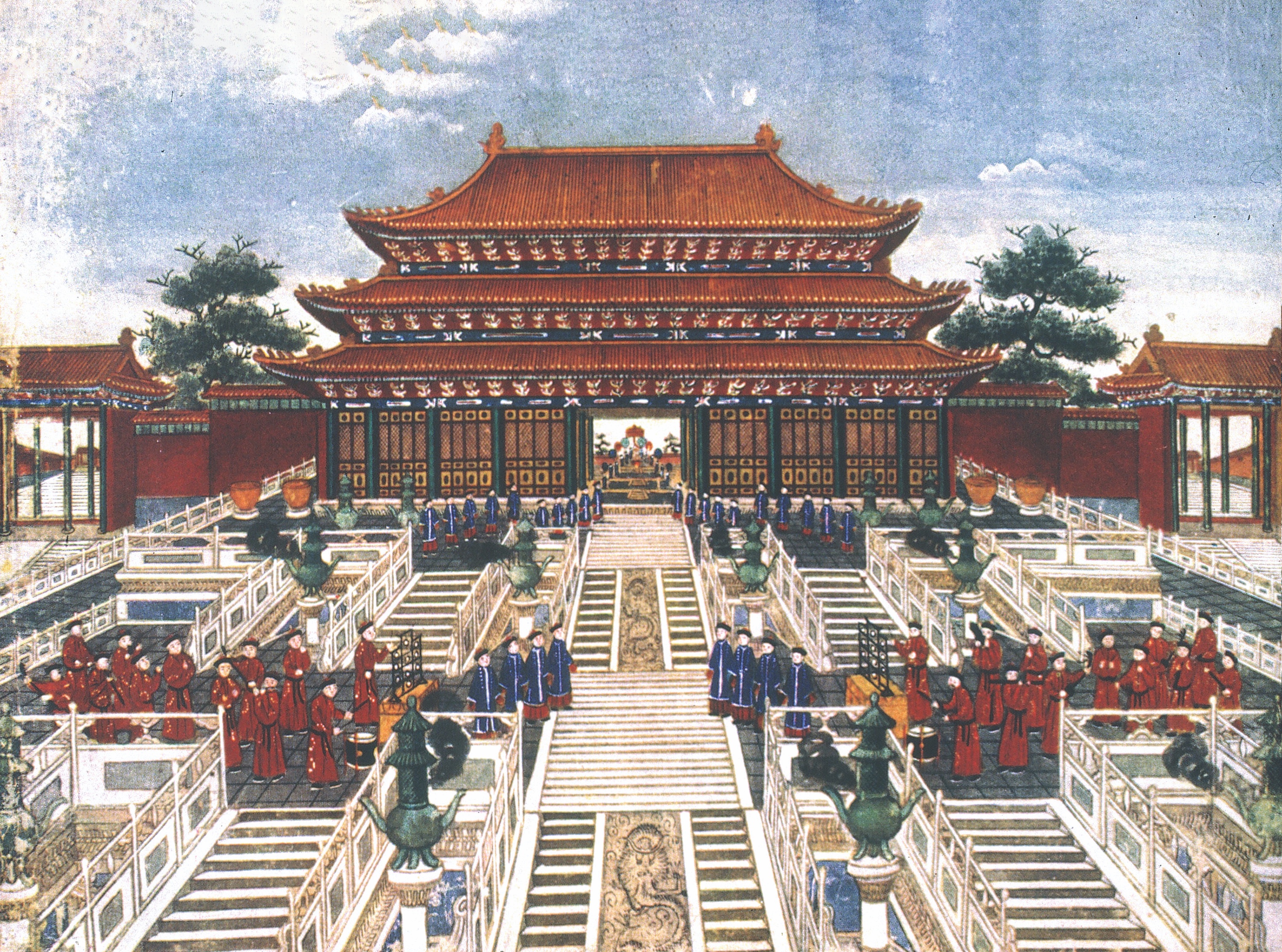

The new emperor appointed Ma He the grand director of the Directorate of Palace Servants, a powerful domestic position. He also gave him a new name, Zheng He (鄭和), in honor of his key role in the fighting around Zhenglunba. Yongle then launched a series of ambitious projects to enhance the grandeur and scope of Ming China and embellish his own image after his violent ascension to the throne. These projects included invading Annan (northern Vietnam), prolonging the conflict with the Mongols, moving the imperial capital to his old stronghold of Beijing, and constructing the massive palace complex known as the Forbidden City.

Even more extravagant was Yongle’s creation of a massive foreign expeditionary armada to impress other nations with the power and wealth of Ming China. Although Zheng He had no naval experience, the emperor named his trusted aide commander in chief of the fleet. As a further sign of his trust, the emperor gave Zheng He blank scrolls stamped with the imperial seal so that he could issue imperial orders of his own while at sea.

China had developed extensive oceangoing merchant fleets and a strong navy earlier in its history, particularly in the 12th and early 13th centuries, when Mongol incursions forced the Song Dynasty to turn to foreign trade to offset its declining agricultural economy. Later, the Yuan Dynasty, founded by Genghis Khan’s Mongol heirs, also created massive war fleets for the purpose of invading Japan and Indonesia.

Before Zheng He could embark on his first epic voyage, he had to supervise construction of the fleet, which required gathering massive supplies of wood and other materials from throughout the empire and conscripting tens of thousands of craftsmen and common laborers to build the ships. Obtaining and transporting the material and workers to the Longjiang shipyard on the Yangtze River east of Nanjing imposed tremendous burdens on provinces far from the capital.

Although Ming China was probably the world’s richest nation, the emperor’s grandiose endeavors ultimately drained the imperial treasury, requiring higher taxes and the printing of ruinous amounts of paper money—a novel concept at the time—to finance them. At first, the fleets varied in size from 200 to 300 ships each. The largest and most impressive were 62 enormous baochuan, or treasure ships, ranging from 385 feet long by 157 feet wide to 440 feet long by 180 feet wide, with displacements estimated to be as high as 30,000 tons.

Even the smallest of them would have been by far the largest wooden vessel ever built—five times larger than their European counterparts. The largest ships that Vasco da Gama sailed from Portugal to India and that Christopher Columbus sailed from Spain to the Caribbean were just over 60 feet long and displaced less than 300 tons. All of their ships could have been stored on the deck of just one of Zheng He’s vessels.

The massive treasure ships were broad beamed and flat bottomed, with no keels and shallow drafts to allow them to traverse the Yangtze, which had an average depth of about 26 feet. European ships, by contrast, had round bottoms with considerable drafts, thick keels for longitudinal strength, and frames at right angles from their keels. The treasure ships’ structural strength was provided by external longitudinal timbering above the waterline and, most important, by transverse bulkheads spaced at regular intervals, which divided the hold into watertight compartments. The concept of watertight spaces to minimize the danger of ruptures below the water line did not emerge in Western ships until the late 18th century.

The transverse bulkheads also allowed Chinese builders to place the treasure ships’ steep masts off center, while Western vessels had to have their masts along the center line to anchor them in the keel. The off-center arrangement allowed the treasure ships’ nine masts to be angled across their broad decks in three rows of three, exposing their 12 large sails to more wind. The yardarms hosting the large square sails were attached to the masts in a manner that allowed them to swing around as needed to better catch the wind during tacking. Men on deck could raise or lower the yards and sails with ropes threaded through pulleys at the top of the masts, so sailors didn’t have to climb the masts as they did aboard Western ships.

Treasure ships were not designed to be fighting ships. Instead, they were more like floating castles, with grand cabins, windows, and antechambers sporting balconies and railings. The hulls were decorated with carved and brightly painted animal heads with glaring dragon eyes at the bow. The sterns were embellished with dragon, eagle, and phoenix patterns symbolizing auspiciousness.

The ships that would carry Zheng He and other senior leaders were crammed with expensive gifts for rulers they planned to visit, including lavishly embroidered silk robes and delicate porcelain. The treasure ships were supported by 200 or more other vessels, smaller but still far larger than anything else afloat at the time. The fleet included eight-masted ships that carried gift horses, seven-masted supply ships, six-masted troop transports, water tankers, and two types of warships—five-masted 165-foot-long fuchuan (escort vessels) and smaller hand-rowed patrol ships.

Under the emperor’s orders and with Zheng He’s guidance, more than 1,600 ships were built during the three-decade existence of the treasure fleets. Each fleet would carry about 28,000 men, including Zheng and his commanders, sailors, craftsmen, and thousands of soldiers. The command element was topped by 70 eunuchs, including Zheng He. Below the eunuchs were 300 military officers of various ranks, from regional commissioners to battalion and company commanders, along with judicial officers to handle military offenses at sea. On board were also 200 civilians, including doctors and pharmacologists (to collect medicinal plants), directors from the Ministry of Finance, and two protocol officers from the Court of State Ceremonial, in charge of receptions for the foreign tributary envoys. Additionally, there were astrologers and geomancers, who were responsible for making astronomical observations, forecasting the weather and interpreting natural phenomena, and 10 foreign language translators.

Each ship captain was specifically appointed by the emperor and given the power of life or death to maintain discipline on board. Crews included hundreds of sailors of various ranks and skills as well as blacksmiths, caulkers, sailmakers, and others needed to maintain the vessels. The ships communicated through an elaborate system of sound and sight signals, with flags, bells, drums, and gongs in daylight and used lanterns to communicate at night. Carrier pigeons enabled long-range communications.

Navigators used a compass consisting of a fish-shaped magnetized needle floating in a basin of water. They determined latitude by gauging the height above the horizon of Polaris or the Southern Cross with a simple measuring board called a qianxingban and marked time by burning graded incense sticks. They also used star charts that noted sailing directions and durations of watches.

Departure and return of the fleet were governed by the seasonal monsoons that could provide favorable winds. The ships would sail from Nanjing to the mouth of the Yangtze, where the fleet would be organized. It then went down the coast 400 miles to a large harbor by the entrance to the Min River, where it waited for months for the northeast monsoon in late December or early January before sailing south-southwest across the South China Sea. The return trip would depend on the beginning of the southwestern monsoon in the spring a year later.

In the autumn of 1405, after offering prayers to Tianfei, the “Princess of Heaven” and the patron goddess of sailors, Zheng He and his men set sail on their first voyage. Its ultimate destination was Calicut (now Kazhikode), a major trading port for spices and rare woods on the southwest coast of India, known in China as the “great country of the western ocean.” The first port of call was the friendly Vietnamese city of Champa. Then the fleet sailed on to Majapahit, on northeast Java. It turned northwest through the Strait of Malacca for stops at Aru and Samudera, on the northern coast of Sumatra, and Aceh on the western tip of the island. But it bypassed Palembang, the most important city-state on Sumatra, where a Chinese pirate, Chen Zuyi, had taken control of the city and was plundering ships passing through the narrow strait.

The fleet faced a long, open-water voyage across the Indian Ocean to a port on the west coast of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Encountering a hostile reception from the Ceylonese king, the fleet left quickly and sailed around the tip of India to Calicut. Although the Chinese referred to most other non-Chinese people as barbarians, they treated the ruler of Calicut as an equal and had the utmost respect for his highly structured society with an efficient civil service, well-trained army and navy, and harsh system of justice.

In the spring, when the monsoon wind shifted to the southwest, the fleet headed back across the Indian Ocean, carrying with it envoys from Calicut, Quilon (another Indian city-state), and the Sumatran states of Samudera, Deli, and Malacca, bearing tributary gifts for the emperor. Before it could reach Nanjing, the fleet had to deal with Chen Zuyi and his pirates, who now were blocking the Straits of Malacca on the eastern coast of the island. When Zheng He demanded that the pirate chief surrender, Chen Zuyi agreed, though he was secretly plotting to ambush the treasure fleet.

Warned of the subterfuge by a local informant, Zheng He attacked first, beginning a monthslong battle in the twisting river channels and mangrove swamps off the straits. Although China had already developed gunpowder, Zheng He’s warships had no cannons. Instead, the ships used various other types of fire weapons, including “sky flying tubes” that sprayed gunpowder and flaming bits of paper, and compact gunpowder-and-paper grenades that emitted noxious fumes and metal pellets like shrapnel. The projectiles were launched from the ships by tension-powered catapults. Zheng He also employed skilled archers who could shower enemy ships with flaming arrows. During the prolonged fighting, the imperial warships burned 10 of Chen Zuyi’s ships and captured seven others, killing more than 5,000 of the pirates and capturing Chen Zuyi and his principal lieutenants. Zheng He then installed his helpful informant as the new ruler of Palembang.

Back in Nanjing, the emperor rewarded the fleet’s seamen for their victory and had the pirate leaders publicly executed. He ordered a second voyage in 1407 to sanction the installation of a new king of Calicut. On that two-year voyage, Zheng He used the visible might of the fleet to ensure a friendlier reception from the empire of Majapahit, whose previous king had killed Ming envoys. The fleet largely retraced the route of the first voyage, eventually dropping anchor in Champa, Brunei, Malacca, Java, Thailand, Sumatra, India, and Ceylon.

In 1409 Yongle ordered a third expedition, during which the armada used its power to punish the hostility and lack of respect shown by Alakeswara, the king of Ceylon, who had previously refused to pay tribute to the Chinese emperor. Now Alakeswara sent his son to demand gold, silver, and other precious objects from the Chinese fleet. When Zheng He refused, the king ordered 50,000 troops to seize the admiral, who had gone ashore with a small force.

This occasioned a prolonged land fight—the only battle fought on land during Zheng He’s seven voyages—in which the admiral demonstrated his skill as a commander in ground warfare. When he discovered that the Sinhalese soldiers had cut down trees to block his way back to the coast, Zheng He reasoned that since most of the enemy forces were heading toward the fleet, there must be only a few left behind to defend the capital. He sent messengers to the fleet, ordering them to resist to the end. He then marshaled the forces at hand, about 2,000 men, quickly marched to the capital, stormed through its protective walls, and seized the king, his family, and his principal chieftains.

The Sinhalese forces returned and surrounded the city, but Zheng He defeated them and rejoined the fleet with his prisoners. Back in China in June 1411, the emperor took pity on the Sinhalese king and his charges as “ignorant people who were without knowledge of the Mandate of Heaven” (the divine right of imperial rule). He released the king and ordered the minister of rites to pick a worthy member of the king’s family to replace him. In the following months, a stream of tribute-bearing rulers and ambassadors traveled to the Ming court from countries the treasure fleet had visited, providing the recognition that Zhu Di had been seeking.

In December 1412, the emperor ordered a fourth voyage to extend the empire’s reach beyond India to the major trading port of Arabia. Departing in January 1414, the fleet followed the usual path until it reached Samudra, on the northeast coast of Sumatra, where Zheng He sought to reestablish order after seven years of internecine conflict. The son of the former king, who was engaged in a guerrilla war with the late usurper’s younger brother, Sekander, had petitioned the Ming court for recognition and support. On arriving, Zheng He ignored Sekander and showered imperial gifts on the prince. Enraged by the slight, Sekander led 10,000 men against Zheng He, who warded off the assault with his large, well-trained army and captured Sekander and his family.

The fleet followed its usual route to Calicut. But instead of lingering to trade, it set off on a long open-water journey across the Arabian Sea to Hormuz, at the entrance to the Persian Gulf. Hormuz was a prosperous meeting place for traders from India and farther East and those who came from Arabia, Africa, and Central Asia by sea and overland. There, Zheng He met merchants from the African city-states of Mogadishu, Brawa (present-day Somalia), and Malindi (Kenya), whom he persuaded to return with him to China and pay tribute to the emperor.

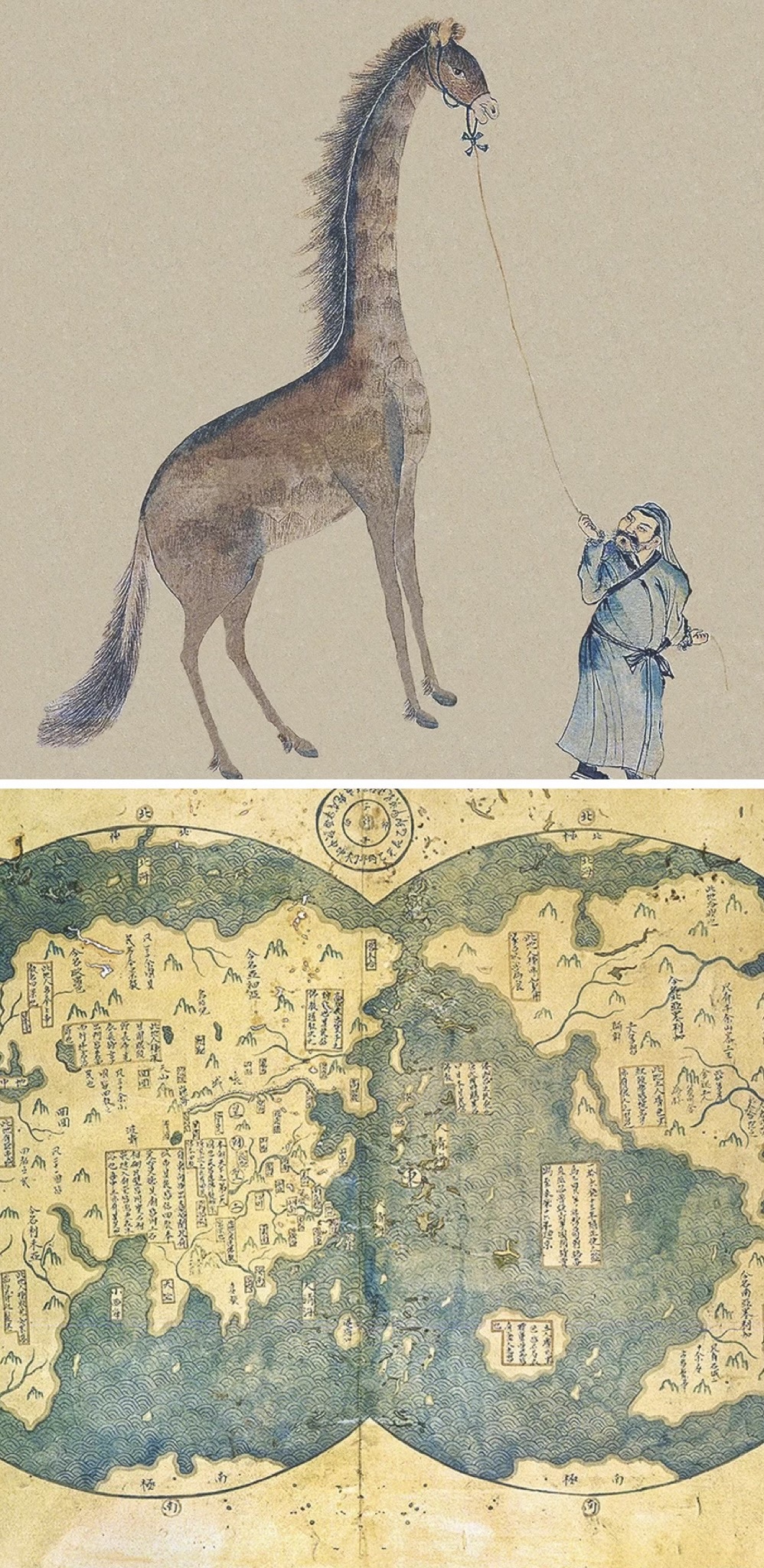

While Zheng He traveled to Hormuz, the eunuch Yang Min took a squadron to Bengal and escorted the new king to China. The king presented Zhu Di with gifts, including a giraffe, which the Chinese mistook for the mythical gilin, a sacred animal in China that was believed to appear only in times of great peace and prosperity. Representatives from 30 different countries accompanied the fleet on its return to China.

Among the thousands of sailors, soldiers, and court officials who accompanied Zheng He on his fourth voyage was a fellow Chinese Muslim, Ma Huan, who later wrote one of the world’s first travel books, The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores, an invaluable source for the sights, sounds, and tastes encountered by the Chinese voyagers on Zheng He’s seven voyages across the Indian Ocean between 1405 and 1433.

Ma Huan was apparently in his early 30s when he joined Zheng He’s fourth voyage in 1413 as a translator. A native of the coastal township of Kuaiji, within the modern borders of Shaoxing, Ma Huan was well educated. His writings show a familiarity with classic Chinese and Buddhist works, and he learned (or taught himself) Persian and Arabic in the course of his travels. He put his language skills to use in describing the exotic, fascinating, and sometimes horrifying sights he and his comrades encountered on their voyages abroad.

Ma Huan described in minute detail the beguiling varieties of food, drink, and plant and animal life in the countries he visited. In Champa, his first stop, the writer dined on succulent jackfruit, with “morsels of yellow flesh as big as a hen’s egg and tasting of honey.” He documented 10 different uses for coconut, ranging from sweet syrup, wine, and oil to the production of rope fibers, thatched roofs, and shell bowls.

In Java, Ma Huan was amazed by the strange birds, including cockatoos, mynahs, and parrots, “all of which can imitate human speech.” He was less impressed with the human residents, who struck him as violent and confrontational. Ma Huan observed that Javanese from the ages of 3 to 100 routinely carried knives and noted that “if a man touches their head with his hand, or if there is a misunderstanding about money at a sale, or a battle of words when they are crazy with drunkenness, they at once pull out these knifes and stab each other.”

In general, Ma Huan was nonjudgmental, merely observing and pondering foreign marriage and funeral rites, domestic relationships, languages and dialects, and various local religious and political practices. He introduced to Chinese writing such words as raja for Indian prince, mahalazha for king, and sakala for sackcloth. He even appears to have described the Biblical figure Moses, whom he called “Mouxie.”

After Zheng He arrived back in Nanjing in August 1415, Zhu Di ordered a fifth voyage, which would extend his reach even farther. The emperor then went north to proclaim Beijing as the new imperial capital, supervise construction of the Forbidden City, and command three more campaigns against Mongolia. He never returned to Nanjing. On the fifth expedition, the fleet made stops at Champa, the usual ports in Indonesia, and the Malay peninsula, and then proceeded to India and Hormuz. It traveled south to Aden on the southeastern tip of Arabia (now Yemen), the main trading port connecting the Mediterranean to India and the Far East. From Aden, the fleet sailed for the African coast, to return the ambassadors from Mogadishu, Brawa, and Malindi to their homes.

The fleet returned to Nanjing in August 1419 and Zhu Di, still in Beijing, ordered a sixth voyage. The fleet left in spring of 1421 and returned to Calicut, where it divided, with elements sailing on to Hormuz, Aden, and western Africa to return visiting dignitaries and bring back new ones. While the fleet was gone, Zhu Di ordered a suspension of the voyages. He died in August 1424, as he was returning from a last futile campaign against the Mongols. His eldest son, Zhu Gaozhi, ascended the throne and ordered a permanent ban on future voyages. The ships were to remain in Nanjing, with Zheng He commanding the military garrison.

When Zhu Gaozhi died nine months later, his son, Zhu Zhanji, became emperor and ordered one last voyage, supposedly out of concern that tribute-bearing ambassadors from the countries of the Indian Ocean were no longer coming to China. Because of deterioration to the ships during the long delay, however, the fleet was not able to sail from China until January 1432. The fleet divided again in Calicut; Zheng He, apparently in ill health, remained there while the main fleet sailed on to Hormuz, Aden, and the African coast. The fleet reunited on the way home.

Ma Huan rejoined Zheng He on his sixth and seventh voyages. As a practicing Muslim, Ma was particularly honored to visit Mecca in 1432, leaving behind perhaps the first outside description of pilgrims on their hajj to Mecca in what Ma termed “the Country of the Heavenly Square.” At the Kaaba shrine, “each year on the tenth day of the twelfth moon, foreign Muslims come to worship,” he wrote. “The men wear long garments, the women all wear a covering over their heads and you cannot see their faces.” Some made journeys lasting a year from every corner of the earth.

Before reaching China in July 1433, Zheng He died and was buried at sea with Muslim ceremonies. He was 62. The fleet never sailed again and the massive vessels rotted in port at Nanjing.

When Zhu Zhanji died in 1435, control of the Ming court devolved to his mother, the grand dowager empress, ruling on behalf of her grandson, Zhu’s son, who was still a minor. She agreed with the Confucian civil officials who had always opposed the voyages because of their expense and their eunuch leadership. With bans on oceangoing ships, Ming China’s maritime presence declined precipitously after 1435. By the early 1500s, Portuguese seamen in vessels a fifth the size of the treasure ships dominated Indian Ocean trade and began to conquer and occupy ports in Arabia, India, and Malacca, while Zheng He’s massive ships were allowed to rot in Chinese harbors.

In the coming three centuries, the Portuguese would be followed by Dutch, British, and French fleets, which would take advantage of China’s lack of a defensive fleet and antiquated army to victimize the Manchu-dominated Qing Dynasty, claiming Macau and Hong Kong. In the mid-1800s the British would wage the shameful Opium Wars, a period that modern Chinese scholars would decry as the nation’s “century of humiliation.”

Nevertheless, Zheng He’s remarkable career represented an expansive projection of sea power that was unique in Chinese history. The admiral’s expeditions established Ming China as the dominant maritime power in Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, and on to Arabia and western Africa for three decades and played an important role in China’s drive to erase the memory of a century of humiliation. The generally peaceable long-term effect of the Ming fleet’s deployments contrasted favorably with the brutal conquest and colonization by the European mariners.

Fittingly, Zheng He had the last word on his great explorations. At the port of Changle in Fujian Province, he oversaw the installation of a giant granite pillar listing the more than 30 countries he and his sailors had visited in their efforts “to manifest the transforming power of virtue and to treat distant people with kindness.” He concluded with a poetic flourish: “We have traversed more than one hundred thousand li [40,000 miles] of immense water spaces and have beheld in the ocean huge waves like mountains rising sky-high, and we have set eyes on barbarian regions far away hidden in a blue transparency of light vapors, while our sails loftily unfurled like clouds day and night.”

Few other voyagers, then or now, could say as much. MHQ

Otto Kreisher, a veteran Washington reporter and former U.S. Marine Corps and Navy Reserve officer, has covered American combat operations in Grenada, Panama, Kuwait, Somalia, and Haiti and—from an aircraft carrier—during Operation Iraqi Freedom.