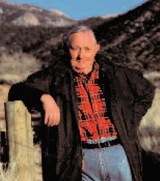

Award-winning Western author Tony Hillerman died Sunday, October 26, 2008, of pulmonary failure in Albuquerque, N.M. He was 83. Hillerman, who was Wild West editor Gregory Lalire’s former journalism professor at the University of New Mexico, sat down for the following interview with Wild West in June 2008:

Award-winning Western author Tony Hillerman died Sunday, October 26, 2008, of pulmonary failure in Albuquerque, N.M. He was 83. Hillerman, who was Wild West editor Gregory Lalire’s former journalism professor at the University of New Mexico, sat down for the following interview with Wild West in June 2008:

Tony Hillerman’s Latest Literary Honor Is the prestigious Owen Wister Award

His knowledge of the Navajos is no mystery

Few writers have matched Tony Hillerman’s success. Most celebrated for his contemporary mystery novels featuring Navajo tribal policemen Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee, Hillerman’s accolades are as numerous as his appearances on best-seller lists. Mystery Writers of America has honored him with the Edgar award for Best Mystery Novel for Dance Hall of the Dead (1974) and its Grand Master Award. Western Writers of America has presented him with Spur Awards for Best Western Novel for Skinwalkers (1986) and The Shape Shifter (2006).

On June 14, during the closing banquet of the Western Writers of America Convention in Scottsdale, Ariz., Hillerman will be honored with the Owen Wister Award (previously known as the Levi Strauss Saddleman Award) for lifetime contribution to the literature of the American West, joining a who’s who of literary icons such as David Dary, Max Evans, Will Henry, Elmer Kelton, Dorothy M. Johnson, Robert M. Utley and John Jakes.

After graduating from the University of Oklahoma, which he attended on the GI Bill after World War II, Hillerman got his start as a journalist in Texas, Oklahoma and New Mexico. He wrote nonfiction essays—many of which appear in his book The Great Taos Bank Robbery and Other Indian Country Affairs—while teaching journalism and serving as what he calls President Tom Popejoy’s “handyman and doer of undignified deeds” at the University of New Mexico.

Despite turning 83 in May, Hillerrman finds it hard to walk away from writing. He took a break from writing an essay and planning another novel at his Albuquerque, N.M., home to talk about the Owen Wister Award, his interest in writing and sharing a few war stories (he was a decorated U.S. Army soldier in World War II).

What are you reading now?

The Worst Hard Time [by Timothy Egan] and, boy, does that bring back all sorts of memories. I remember looking out the kitchen window across a cotton yard in Sacred Heart, Okla., to see if my dad was coming home. The cotton yard was maybe 60 yards wide, and it was noon and the dust was so thick you couldn’t see across the cotton yard. We were poor. Of course, nobody knew they were poor. I had no idea. Everybody was poor. We weren’t any poorer than anybody else.

What did you read as a boy?

Everything I could get my hands on.… We had the state library. If you wrote them a letter, they would send you a list of books and then you’d send them a list of what you wanted to check out and money to cover the postage. I’d be asking for War and Peace, or cowboys and Indians, combat, war stuff, aviation. I still remember opening the first package and pulling out History of the Masonic Order in the West. Then there was Recovery of the Cotton Industry in South Carolina. Stuff like that. But I read them.

What made you want to write?

Well, I always enjoyed reading.… I got in the Army, got in a rifle company…well, everybody in my company decided when the war was over we were going to circulate a petition, ask Congress to abolish West Point, tear down all the West Point buildings, salt the ground so it wouldn’t spring back up and then get Congress to enact a Constitutional amendment banning people who could not pass a fourth-grade intelligence test from gaining a commission in the United States Army.

We had been screwed up by West Point officers. We were at a little town in France, close to the German border. The Germans held the other side of the stream, and we held our side. And the West Pointers decided they wanted us to go to the other side and capture two Germans.… We got ready to go, and they called it off. The next morning, they decided we would go that night. By now, everybody on both sides knew we were going over there. We got up to the front, and one of the guys said: “Surely you’re not going over there. The Germans have been working all day—we’ve been watching them—and getting ready for you guys.”

Boy, were they ready. We just got the hell kicked out of us. I got blown up in a barnyard. The first guy who carried me back got shot, but the next guy dumped me in the creek. Anyway, I got back. I couldn’t see much—the Army still rates this eye as blind—both of my knees were broken, and my left foot had been rebuilt so that I still have to buy shoes two different sizes. But I was sitting in a wheelchair, thinking that the Army doesn’t have any use of me anymore, and I knew I didn’t want to farm. I started thinking that maybe I’d like to write, and I started writing a short story in my mind. It wasn’t very good. In fact, it’s pretty bad, but I finally put it on paper, got it published and that encouraged me.

In Oklahoma you must have grown up around Indians.

On our high school football team, the backfield was largely Seminole, and the line was Pottawattamie, and our coach was a Choctaw. He taught algebra. No girls took algebra. What we did in algebra class was study the single-wing, double-wing formations and blocking assignments.

What got you interested in the Navajos?

I had just gotten back from the war, didn’t have a job, didn’t know anybody and went to a USO dance [in Oklahoma City]. I met a very pretty girl with long red hair, and I asked her to dance. I liked her, and she seemed to like me. She told me her dad needed a driver. He had drilled a wildcat well on the Indian reservation. I didn’t have a driver’s license, never had one, had a patch over my left eye, but her dad drove the big truck, and I followed in a smaller one with his red-haired daughter sitting beside me. That was the first time I saw the city of Albuquerque.

Along about Crownpoint, we pulled off the main highway onto a dirt road, and coming out of the hills was a whole column of Navajos. I was used to Indians, but these guys were really dressed up, all on horses, men and women, and we stopped to let them go. When we got to the ranch, I asked the rancher about those Navajos. He said some of the boys had just got back from the Marine Corps, and they’re having an Enemy Way ceremony, a curing ceremony. I said, “Boy, I’d like to see that.” He said if you stay sober and mind yourself, it would be all right. So I went.

Along about Crownpoint, we pulled off the main highway onto a dirt road, and coming out of the hills was a whole column of Navajos. I was used to Indians, but these guys were really dressed up, all on horses, men and women, and we stopped to let them go. When we got to the ranch, I asked the rancher about those Navajos. He said some of the boys had just got back from the Marine Corps, and they’re having an Enemy Way ceremony, a curing ceremony. I said, “Boy, I’d like to see that.” He said if you stay sober and mind yourself, it would be all right. So I went.

What was it like?

What impressed me about it was how all their kin showed up. They weren’t curing bullet wounds or broken bones. The whole point was to teach them to get rid of their bad memories, their anger, hatred and indignation for the way they’d been treated, been shot at, just to get them back in what they call Hozjo, harmony with the world. I thought: “Boy, that’s wonderful; that’s the way it ought to be.” Nobody greeted me. I would have liked to have somebody tell me it would be all right. That stuck in my mind.

And became the basis of your first novel, The Blessing Way. Where did Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee come from?

My first newspaper job was as a police reporter in Borger, Texas, where I met the sheriff of Hutchinson County…I used him as a model for Joe Leaphorn, the way his mind worked. A nice guy. I don’t remember how Jim Chee started. I didn’t have anyone in mind, but I was teaching [at the University of New Mexico] and thinking of all the students I had, bright guys, young, had their own ideas about things. So I put him in there for the chance to open up some new doors.

Was it hard to research the Navajos?

Growing up with Indians in Oklahoma, I knew how they are. In the first place, you don’t want them thinking you think they’re absurd or odd. You let them know you’re really interested, as I really was, and before long I could ask them about taboos, holy people. I got acquainted with a couple of archaeologists, and the basement of the [university] library had rows and rows of papers of sociologists, anthropologists, writings about all sorts of stuff, describing sweat lodges, various types of initiations, taboos and inhibitions. I spent many a night and many hours reading those, and then I’d ask the Navajos about it. I got called on mistakes in my novels, like when I’d mention a guy getting off interstate so-and-so and turning right to go to Gallup when he should have turned left, stuff like that, but the religious stuff, I was very careful with that.